Copyright 1903 by G. Barrie & Sons

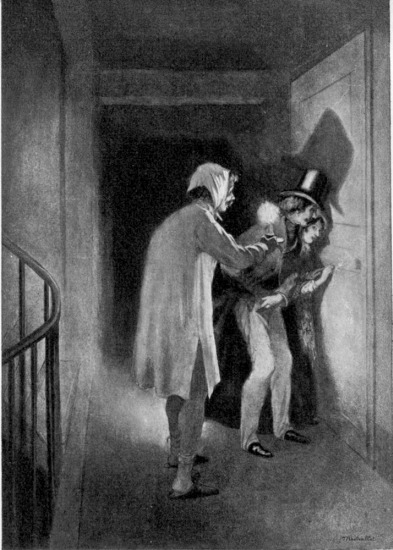

RAYMOND SURPRISES DORSAN AND NICETTE

I was determined that he should not, at all events, have time to scrutinize the girl; I fumbled hastily in my pocket for my key, but it was entangled in my handkerchief.

THE JEFFERSON PRESS

BOSTON NEW YORK

Copyrighted, 1903-1904, by G. B. & Sons.

I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, XXVI, XXVII, XXVIII, XXIX, XXX, XXXI, XXXII, XXXIII, XXXIV, XXXV, XXXVI.

I was strolling along the boulevards one Saturday evening. I was alone, and in a meditative mood; contrary to my usual custom, I was indulging in some rather serious reflections on the world and its people, on the past and the present, on the mind and the body, on the soul, on thought, chance, fate, and destiny. I believe, indeed, that I was on the point of turning my attention to the moon, which was just appearing, and in which I already saw mountains, lakes, and forests,—for with a little determination one may see in the moon whatever one pleases,—when, as I was gazing at the sky, I suddenly collided with a person going in the opposite direction, whom I had not previously noticed.

“Look where you’re going, monsieur; you’re very awkward!” at once remarked a soft, sweet voice, which not even anger deprived of its charm. I have always had a weakness for pleasant voices; so I instantly descended from the regions to which I had mounted only for lack of something better to do, and looked at the person who had addressed me.

It was a girl of sixteen to eighteen years, with a little cap tied under her chin, a calico dress, and a modest apron of black mohair. She had every appearance of a young workgirl who had just finished her day’s work and was on her way home. I made haste to look at her face: a charming face, on my word! Bright, mischievous eyes, a tiny nose, fine teeth, black hair, and a most attractive ensemble; an expressive face, too, and a certain charming grace in her bearing. I was forced to confess that I saw no such pretty things in the moon.

The girl had under her arm a pasteboard box, which I had unwittingly jostled; she refastened the string with which it was tied, and seemed to apprehend that the contents had suffered from my awkwardness. I lost no time in apologizing.

“Really, mademoiselle, I am terribly distressed—it was very awkward of me.”

“It is certain, monsieur, that if you had looked in front of you this wouldn’t have happened.”

“I trust that I have not hurt you?”

“Me? oh, no! But I’m afraid that my flowers are crumpled; however, I will fix them all right at home.”

“Ah!” said I to myself; “she’s a flowermaker; as a general rule, the young ladies who follow that trade are not Lucretias; let us see if I cannot scrape acquaintance with her.”

She replaced her box under her arm, and went her way. I walked by her side, saying nothing at first. I have always been rather stupid about beginning gallant interviews; luckily, when one has once made a start, the thing goes of itself. However, from time to time I ventured a word or two:

“Mademoiselle walks very fast. Won’t you take my arm? I should be delighted to escort you. May I not be permitted to see you again? Do you go to the theatre often? I could send you tickets, if you chose. Pray be careful; you will surely slip!” and other polite phrases of that sort, the conventional thing in nocturnal meetings.

To all this I obtained no reply save:

“Yes, monsieur;” “no, monsieur;” “leave me, I beg you!” “you are wasting your time;” “don’t follow me.”

Sometimes she made no reply at all, but tossed her head impatiently, and crossed to the other side of the boulevard. But I crossed in her wake; and after a few moments of silence, I risked another remark, giving to my voice the most tender and sentimental inflection conceivable.

But I began to realize that my chance acquaintance was shyer than I had at first supposed, and that I might very well have nothing to show for my long walk, my little speeches, and my sidelong glances. However, her resistance augmented my desires; I remembered how foolish I felt one evening when, thinking that I had fallen in with an innocent maid, my charmer, when we arrived at her door, invited me to go up to her room; and I beg my readers to believe that I knew too much to accept. But appearances are so deceptive in Paris! the shrewdest connoisseurs allow themselves to be cozened; now, I ought to be a connoisseur, for I have seen a good deal of the world; and yet, I frequently allow myself to be taken in.

I made these reflections as I followed my pretty flower girl. She led me a devilish long way; we walked the whole length of Boulevards Montmartre, Poissonnière, Bonne-Nouvelle; we passed all the small theatres. “She lives in the Marais,” I thought; “that is plain.” We went through Rue Chariot, Rue de Bretagne, Vieille Rue du Temple. We went on and on; luckily, the weather was fine, and I knew that she must stop sooner or later. Yes, and she would probably shut the door in my face; but what did I care? After all, I was simply killing time; I had not known what to do with myself, and I had suddenly found an objective point for my stroll. To be sure, such an objective point is within the reach of everyone in Paris; and it is easy to provide one’s self with occupation by following the first saucy face one chances to meet. Indeed, I know many men who do nothing else, and who neglect their business to do it. Above all, I notice a large number of government clerks, who, instead of attending to their duties, are constantly hunting grisettes, on the pretext of going out to buy lunch; to be sure, they go out without their hats, and run about the city as if they were simply making neighborly calls; which is very comforting for the departments, as they are always sure that their clerks are not lost.

But it is not my business to censure the conduct of other people; indeed, that would be a most inopportune thing to do, inasmuch as I am in the very act of setting a bad example; for, a moment ago, I was meditating upon the instability of human affairs, and now I am giving chase to a petticoat that covers the most fragile, the weakest, the most deceitful, but also the most seductive, most alluring, most enchanting creature that Nature has created! I was losing my head, my imagination was hard at work, and yet I saw only a foot—a dainty one, ’tis true—and the beginning of a leg clothed in a modest black woollen stocking. Ah! if I might only have seen the garter! Faith! all things considered, it is much better to follow a girl, at the risk of having a door shut in your face, than to try to read the moon, and to weary one’s brain with metaphysics, astronomy, physiology, and metoposcopy; the deeper one delves into the vague and the abstract, the less clearly one discovers the goal and the proof; but, turn your attention to a saucy face, and you know at once what you wish to accomplish; and in the company of a pretty woman it is easy to discover the system of nature.

For several minutes I had said nothing to my young working girl; I was piqued by her persistent silence; I had even slackened my pace, so that she might think that I had ceased to follow her. But, although I was some twenty yards distant, I did not lose sight of her. She stopped, and so did I. She was speaking to someone; I walked toward them. The someone was a young man. I bit my lips in vexation; but I tried to distinguish what they were saying, and I overheard the following dialogue:

“Good-evening, Mademoiselle Caroline!”

“Good-evening, Monsieur Jules!”

“You are going home very late.”

“We have lots of work, especially on Saturday; and then I had a box to carry to Rue Richelieu; that is what makes me so late.”

“What have you got in this box?”

“A pretty bunch of roses to wear in my cap to-morrow. I made it myself; it’s very stylish, as you’ll see. A clumsy fellow ran into me on the boulevard, and nearly made me drop it.”

At that, I slunk into the passageway in front of which I had stopped.

“There are some people who never pay any attention to anything when they’re walking.”

“I fancy this man was a student; he was looking at the sky.”

“Oh, yes!—But I must leave you; my aunt’s waiting for me, and she’ll give me a scolding.”

“I should be very sorry to be the cause of anything unpleasant happening to you. We shall see each other to-morrow, shan’t we?”

“Yes, yes; unless my aunt isn’t willing that I should dance any more. She’s so cross! Have you got tickets for Tivoli?”

“Yes, mademoiselle, for four; I will call for you.”

“Early, Monsieur Jules.”

“Oh, never fear! But don’t you forget we’re to dance the first contradance together.”

“I never forget such things!”

“Adieu, Mademoiselle Caroline!”

“Adieu, Monsieur Jules!”

Monsieur Jules drew nearer to her, and the girl offered her cheek. I heard a kiss. Parbleu! it was well worth while going all the way to Rue des Rosiers to see that!

The young man walked away, singing; the girl went a few steps farther, then entered a passageway, of which she closed the door behind her, and I was left standing in the gutter.

That Jules was evidently her lover; yes, he had every appearance of a lover, albeit an honorable one, for I was certain that he kissed nothing but her cheek; moreover, his conversation did not suggest a seducer. To-morrow, Sunday, they were going to Tivoli, with the aunt, no doubt, as he had tickets for four. Well, it was evident that I should have nothing to show for my walk. It was not the first time, but it was a pity; for she was pretty, very pretty! I examined the house with care. One can never tell—chance may serve one at some time. The street was dark, the moon being behind a cloud, and I could not make out the number. But that was of no importance, for I could recognize the passageway, the sharp corner, and the awning.

“What the devil! Pray be careful what you’re doing! You just missed throwing that on me!”

An inmate of my charmer’s house had opened his window and emptied a vessel into the street, just as I was trying to distinguish the color of the wall. Luckily, I escaped with a few splashes; but the incident abated my curiosity, and I left Rue des Rosiers, wiping my coat tails with my handkerchief.

It was not late when I returned to the boulevard; the performances at the small theatres were not yet at an end. A dozen ticket speculators ran to meet me, offering to sell me checks.

“There’s one more act, monsieur,” they shouted in my ears; “it’s the best of all; you’ll see the duel with a sword and an axe, the fire, and the ballet. It’s a play that draws all Paris. You can go to any part of the theatre.”

Unable to resist such urgent solicitations, I bought a check which entitled me to admission to any part of the theatre; but they would only allow me to go into the pit, or to walk around the corridor. I chose the latter alternative; as there was but one act to be played, I could see well enough; and then, the things that happen in the auditorium are often more amusing than those that happen on the stage. I am rather fond of examining faces, and there are generally some comical ones in attendance upon melodramas; the theatres at which that class of play is given are, as a general rule, frequented by the common people and the middle class, who do not know what it is to conceal their feelings, and who consequently abandon themselves unreservedly to all the emotion aroused by a scene of love or of remorse.

“Ah! the cur! ah! the blackguard!” exclaimed my nearest neighbor whenever the tyrant appeared; “he’ll get his finish before long.”

I glanced at the speaker; I judged from his hands and his general aspect that he was a tanner; his eyes were brighter than those of the actor who played the traitor and against whom he vociferated loudly at every instant. In front of me, as I stood behind the seats, I noticed a laundress who sobbed bitterly as she listened to the story of the princess’s misfortunes, and a small boy who crouched under the bench to avoid seeing the duel.

“How these good people are enjoying themselves!” I thought; “they are not surfeited with the theatre; they are absorbed by what is taking place on the stage; they don’t lose a single word, and for the next week they will think of nothing but what they have seen to-night. I will go up to the first tier of boxes; there is more style there, but less enjoyment.”

Through a glass door I caught sight of a most attractive face; I gave the box opener the requisite amount of money, and entered the box, determined to do my utmost to make up for the time I had wasted with Mademoiselle Caroline.

The lady, who had seemed a charming creature seen through the glass, was less charming at close range. However, she was not unattractive; she had style, brilliancy, and dash. She was still young; I saw at once that she was inclined to flirt, and that the appearance of a young man in her box would divert her for a moment.

You will understand, reader, that I was a young man; I believe that I have not yet told you so. Later, I will tell you who I am, and what talents, what attractive and estimable qualities, I possess; it will not take long.

A gentleman was seated beside the lady in question; he had a commonplace face, but was fashionably dressed and had distinguished manners. Was he her husband? I was inclined to think so, for they hardly spoke to each other.

I regretted that I had only about half an act to see; with more time, I might have been able to enter into conversation, to make myself agreeable, to begin an acquaintance. It seemed to me that I made a favorable impression; she bestowed divers very soft glances on me; she was seated so that she could look at me without being seen by her companion. The ladies are so accustomed to that sort of thing, and so expert at it!

“Ah!” I thought; “if ever I marry, I will always sit behind my wife; for then—— Even so; but if somebody else sits beside her, can I prevent the feet and knees from doing as they will? It is most embarrassing.”

“This play isn’t so bad,” said the lady at last, to her neighbor; “the acting here is not at all amiss.”

“Yes, yes;” nothing but yes. Ah! he was surely her husband. I listened intently, for she was evidently speaking for my benefit.

“I was horribly bored last night at the Français; Mars didn’t act. Aren’t we going to the Opéra to-morrow? There’s to be an extra performance.”

“As you please.”

“After all, it’s too hot for enjoyment at the theatre. If there wasn’t always such a medley in the public gardens on Sunday, I would rather go there than shut myself up in a theatre. What’s your idea?”

“It makes no difference to me.”

The lady made an impatient gesture. The gentleman did not notice it, but moved nearer the front of the box. I rose to look at the scenery, and my hand happened to come in contact with the lady’s arm, but she did not move.

“These theatres are wretchedly ventilated; there’s a very unpleasant odor here,” she said, after a moment.

I thought of my coat tails, which, in truth, smelt anything but sweet. I could not help smiling, but I instantly offered her a smelling bottle. She accepted it, and when she returned it did not seem offended because I pressed the hand with which she presented it to me.

At that moment the curtain fell.

“The devil!” I muttered to myself; “what a shame! I came too late. Mademoiselle Caroline is responsible for it. But what am I saying? If it had not been for her, I should still be on Boulevard Montmartre, gazing at the stars; it was because I followed her that I came in here to see the last act; and by running after a grisette I have fallen in with a petite-maîtresse who perhaps is inferior to the grisette! How one thing leads to another! It was because something was thrown on my coat that this lady complained of the unpleasant odor, and that I offered her my smelling bottle and squeezed her hand. After this, who will tell me that there is no such thing as fate? If I should make this gentleman a cuckold, it would certainly be the fault of Mademoiselle Caroline, who refused to listen to me.”

We left the box. I assisted my neighbor to climb over the benches, which were stationary for the convenience of the public. But the husband took her arm, and I was obliged to fall behind.

“Shall I follow, or shall I not follow?”—Such was the question I asked myself as I descended the staircase. After what had happened to me so short a time before, I ought to have kept quiet the rest of the evening; but I was twenty-four years old, I loved the fair sex passionately; moreover, my last mistress had just proved unfaithful to me,—indeed, it was that fact which was responsible for my melancholy meditations,—and a young man who has a strong flavor of sentiment in his makeup cannot exist without a passion. Unquestionably I was——

We were no sooner on the boulevard than they crossed the sidewalk to the curbstone.

“Aha!” I said to myself; “they are going to take a carriage; I’ll just listen to what they tell the driver, and in that way I can learn the address without putting myself to any trouble.”

But it was decreed that I should be disappointed again in my plans. They walked to a dainty vis-à-vis and called André; a footman ran to them, opened the door, and assisted monsieur and madame to enter.

My self-esteem received a still sharper prick; a woman who had a carriage of her own! Here was a conquest that merited the expenditure of some little time and trouble. I determined to follow madame’s carriage—not on foot; that would be too fatiguing! it might do if she were in a cab; but with private horses—why, I should have inflammation of the lungs! I spied a cabriolet, which was just what I wanted. The other carriage was driving away, so I lost no time.

“Hi, cocher!”

“Get in, monsieur.”

“I am in.”

“Where are we going, bourgeois?”

“Follow that carriage just ahead of us, and you shall have a good pourboire.”

The rascal did not need it; I saw that he was already tipsy. I wished then that I had taken another, but it was too late to change. He lashed his emaciated horse with all his strength; the infernal beast broke into a gallop of desperation, and sometimes outstripped the private carriage.

“Look out!” I said to my driver; “don’t whip it so hard; let’s not have an accident.”

“Don’t you be afraid, bourgeois, I know my business; you see, I haven’t been driving a cab twenty years without finding out what driving means. You’re with some friends in the green fiacre yonder; very good! I propose to have you get there ahead of ’em.”

“But I did not tell you that I was with anybody; I want you to follow that carriage; if you pass it, how can you follow it?”

“I tell you, bourgeois, that they’re a-following us; I’ll show ’em that my horse is worth two of theirs. When Belotte’s waked up, there’s no stopping her.”

“Morbleu! you go too fast! We have passed the carriage; where is it now?”

“Ah! they’re trying to catch up with us; but the coachman’s mad. I’m driving you all right, bourgeois.”

“But stop—stop, I tell you!”

“Have we got there?”

“Yes, yes! we’ve got there.”

“Damme! you see, Belotte’s got her second wind, and she’s a good one to go, I tell you. Ho! ho! here you are, master. Where shall I knock?”

“Nowhere.”

“Ha! ha! not a sign of a fiacre anywhere! Didn’t I tell you that you’d arrive ahead of the others? You see, it’s a whim of mine to pass everything on the road.”

I alighted from the cabriolet and looked all about; no sign of a carriage; we had lost it. I was frantic; and I had to listen to the appeals of my drunken driver, who wanted his pourboire. I was tempted to break his whip over his back; but I restrained myself and adopted the quickest method, which was to pay him and dismiss him.

“When you want a good driver and a good horse, bourgeois, I’m your man, you see; you’ll always find me on Place Taitbout, near Torchoni’s—in the swell quarter. Ask for François; I’m as well known as the clown.”

“All right; I’ll remember.”

The villain drove away at last, and I was left alone in a street which was entirely unfamiliar to me. It was getting late, and, as I had no desire to pass the night walking the streets, I tried to discover my whereabouts! After walking some distance I found myself at a spot which I recognized; I was on Rue des Martyrs, near the Montmartre barrier. Luckily, I lived on Rue Saint-Florentin, and to get there I had simply to walk down the hill. So I started, reflecting as I walked. It was a fitting occasion for reflection, and I had plenty of time. But my reverie was again interrupted by outcries. As the Quartier des Porcherons is not frequented by the most select society, and as I was nowise inclined to seek a third adventure at the Grand Salon, I quickened my pace, in order to avoid unpleasant encounters.

But the noise continued; I heard cries and oaths and blows. Women were calling for the police, the magistrate, and all the constituted authorities of the quarter; men were pushing and striking one another and throwing one another into the gutter. Windows were thrown open, and heads appeared enveloped in nightcaps; they listened and laughed and conversed from window to window, asking what the trouble was; but they refrained from going down into the street, because it is not prudent to meddle in a quarrel after dark.

The open windows and the faces surmounted by nightcaps reminded me of my little mishap on Rue des Rosiers. I no longer walked, but flew! fancying that I was pursued by fatality. But I heard someone running behind me; I turned into a street to the right; the footsteps followed me. At last I stopped to recover my breath, and in a moment my pursuer overtook me and grasped my arm.

“O monsieur! save me! take me with you! protect me from that horrible Beauvisage, who swore he’d take me away from anyone. Just hear how he’s beating Cadet Finemouche, who’s a good fighter himself! My sister was no fool; she skipped as soon as the fists began to play, and left me to carry the whole thing on my back; and perhaps she’ll go and tell my mother bad stories about me! I haven’t anybody but you to help me, monsieur; if you won’t, I’m a lost girl.”

While my waylayer recited her story, pausing only to wipe away the tears with the back of her hand, I looked at my new acquaintance and tried to distinguish her features by the dim light of a street lamp.

Her language and her dress speedily informed me what manner of person I had to deal with: a loose red gown, caught in at the waist with a black velvet scarf; a round cap with a broad lace border; a colored neckerchief, tied in front, with a large cross à la Jeannette resting upon it. Mistake in this instance was impossible: it was perfectly evident that I had before me a marchande à éventaire,[A] or one of those hucksters whose booths surround the cemetery of the Innocents.

[A] That is to say, a huckster, or peddler, who goes from place to place with her wares displayed on a tray hung from her shoulders.

My first thought was to see if she was pretty; I found that she was very good-looking indeed. Her eyes, although filled with tears, had a sincere, innocent expression which made her interesting at first sight; her little pout, her grieved air, were softened now and then by a smile addressed to me; and that smile, which the most accomplished coquette could not have made more attractive, disclosed two rows of the whitest teeth, unspoiled by enamel, coral, and all the powders of the perfumer.

However, despite my new acquaintance’s beauty, I was very reluctant to retain her arm, which she had passed through mine. Surely, with such charming features, she could not deal in fish or meat. I was morally certain that she sold flowers; but I did not choose to take a flower girl for my mistress; at the most, I might, if a favorable opportunity offered, indulge in a whim, a fancy. But I was not in luck that evening, and I did not propose to try any more experiments. I determined to rid myself of the girl.

As gently as possible, I detached the arm that was passed through mine; then I assumed a cold expression and said:

“I am very sorry that I am unable to do what you wish; but I do not know you; the dispute between Monsieur Beauvisage and Cadet Finemouche doesn’t concern me. Your sister ran away, and you had better do the same. Your mother may think what she pleases, it is all one to me. It is after twelve o’clock; I have been walking about the streets long enough, and I am going home to bed.”

“What, monsieur! you refuse! you are going to leave me! Think of refusing to go a little out of your way to help a poor girl who is in trouble because of an accident that might happen to anybody. I tell you again that my mother is quite capable of not letting me in if I go home without somebody to answer for me who can swear that I am innocent.”

“And you expect me to swear to that, do you?”

“Pardine! would that skin your tongue? Besides, you’re a fine gentleman, a swell; she won’t dare to fly into a temper before you, and she’ll listen to me. But if I go home alone—what a row! Oh! mon Dieu! how unlucky I am! I didn’t want to go to the Grand Salon at all; I was afraid of something like this.”

And thereupon the tears and sobs began afresh, and she stamped with her little feet. Perhaps her mother would tear out her hair; that would be too bad, for it formed a most becoming frame for that frank, artless countenance. My heart is not made of stone; I was touched by the girl’s distress, and I said to myself: “If, instead of this jacket, she were dressed in silk or even in merino, if she wore a dainty bonnet instead of this round cap, and a pretty locket instead of a cross à la Jeannette, I would long ago have offered my services with great zeal; I would play the gallant and make myself as agreeable as possible; I would cut myself in two to obtain a hearing, and I would regard it as a favor if she would allow me to offer her my arm. And shall this modest costume make me cruel, unfeeling? Shall I refuse to do a trivial favor, which she implores with tears in her eyes? Ah! that would be bad, very bad!”—I had been following a grisette and a grande dame, who perhaps were not worth so much notice as this poor child; I had passed the evening making a fool of myself, and I could certainly devote an hour to a worthy action. I determined to escort my flower girl to her home.

You see, reader, that I sometimes have good impulses; to be sure, the girl pleased me much. “All women seem to please you,” perhaps you will say. True, reader; all the pretty ones; and I venture to say that you are like me.

I drew nearer to my pretty fugitive. She was sitting on a stone, holding a corner of her apron to her eyes, and sobbing.

“Mademoiselle.”

“Mon—monsieur.”

“What is your name?”

“Ni-Ni-i-cette, monsieur.”

“Well, my little Nicette, have courage; stop crying, and take my arm. I will take you home to your mother.”

“Real—Really?”

She jumped for joy; indeed, I believe that she was on the point of embracing me; but she contented herself with taking my arm, which she pressed very close in hers, saying:

“Ah! I was sure that you wouldn’t leave me in such a pickle. I’m a good girl, monsieur; the whole quarter will tell you that Nicette’s reputation’s as clear as spring water. But my mother is so ugly! and then my sister’s jealous because she says I make soft eyes at Finemouche.”

“You can tell me all about it on the way. Where are we going?”

“Oh, dear! it’s quite a little distance. I have a stand at the Croix-Rouge, and I live on Rue Sainte-Marguerite, where my mother keeps a fruit shop.”

From Faubourg Montmartre to the Croix-Rouge! that was enough to kill a man! If only I could find a fiacre! I believe that I would even have taken François’s cabriolet, at the risk of having Belotte take the bit in her teeth; but no carriage of any sort passed us. I had no choice but to make the best of it; so I took Nicette by the arm and forced her to quicken her pace.

“You are a peddler, Nicette,” I said; “what do you sell?”

“Bouquets, monsieur; and they’re always fresh, I flatter myself.”

She was a flower girl; I was sure of it. The certainty restored my courage to some extent, and made the journey seem less long. I should not have been flattered to act as escort to a fishwoman; and yet, when it is a matter of rendering a service, should one be influenced by such petty considerations? But what can you do? that infernal self-esteem is forever putting itself forward. Moreover, I am no better than other men; perhaps I am not so good; you may judge for yourselves.

“Ah! you sell bouquets, do you?”

“Yes, monsieur; and when you want a nice one, come and see me; I will always have some ready for you, day or night.”

“Thanks.—But how does it happen that, living in Faubourg Saint-Germain, you go to a dance near the Montmartre barrier? I should suppose that you could find balls enough in your own neighborhood.”

“I’ll tell you how that happens. My sister Fanchon has a lover, Finemouche, a brewer, a fine-looking, dark fellow, that all the girls in the quarter are mad over. My mother says that he’s a ne’er-do-well, and don’t want Fanchon to listen to him; but Fanchon’s crazy over him, and she tries all sorts of ways to be with him, on condition that he won’t make love to her except with honest motives. This morning she agreed to come to Montmartre at dusk, sentimentally, to have a drink of milk. But she had to make up her mind to take me; mother wouldn’t have let her go alone. We said we were going to see an aunt of ours, who sells oranges on the boulevard; that was a trick of Fanchon’s. I went with her against my will, especially as Finemouche sometimes gives me a look, that I don’t pay any attention to—on the word of an honest girl!—When we got to Montmartre we found the brewer, who treated us both to a donkey ride. After riding round for two hours, I said it was time to turn our toes toward home; but Finemouche says: ‘Let’s rest a few minutes at the Grand Salon—long enough to eat a salad and have a waltz.’—I didn’t want to accept; but my sister likes waltzing and salad, and I had to let her have her way. So we went to the Grand Salon. Fanchon danced with Finemouche; so far, everything went well enough. But, as luck would have it, in comes Beauvisage, a fellow who works in a pork shop on our street. He’s another fellow who makes love to all the girls, and who’s taken it into his head to have a passion for me.”

“You don’t seem to lack adorers, Nicette.”

“I have one or two, but it ain’t my fault. God knows, I always receive ’em with my fists closed. But these men! the crueler you are, the more they hang on! I have shown Monsieur Beauvisage that I don’t like his attentions; I always throw his presents in his face; but it don’t make any difference: just as sure as I leave my stand for a minute, when I come back I find a sausage among my roses, or a pig’s foot on my footwarmer. Why, the other day, my birthday, he actually came to wish me many happy returns, with a white pudding, and truffled at that! But all that don’t touch my heart; I told him that I wouldn’t have him, before all the old gossips of the quarter; and I threw his pudding in his face. He went away in a rage, swearing that he’d kidnap me. So you can imagine that I shivered with fright when I saw him come into the Grand Salon, especially as I know what a hot-headed fellow he is.—Would you believe, monsieur, he had the cheek to ask me to dance, just as if nothing had happened! I refused him flat, because I ain’t two-faced. He tried to force me to dance; Finemouche came running up and ordered him to let me alone instantly, at which he held me all the tighter. Cadet handled him so rough that they went out to fight. My sister Fanchon blamed me, because it made her mad to have her lover fight for me. But the worst of it all is that Finemouche, who had drunk a good deal with his salad, was beaten by Beauvisage. Fanchon ran off as soon as she saw her lover on the ground; I tried to do the same, but my tormentor ran after me. At last I caught sight of you, monsieur, and that gave me courage; I was sure you’d protect me; I grabbed your arm, and that’s all.”

Nicette’s story interested me; and the thing that pleased me most was that she seemed to be virtuous and had no lover.—“What difference did that make to you?” you will say; “as you were a young man in society, of course you would not make love to a flower girl.” True; I had no such purpose; and yet, I became conscious that for some moments I had been pressing the girl’s arm more tenderly than before. But it was because I was distraught.

“Do you think my mother will beat me, monsieur?”

“I don’t see why she should be angry; you have done nothing wrong.”

“Oh! in the first place, we shouldn’t have gone to the Grand Salon.”

“That was your sister’s fault.”

“Yes, but she’ll say it was mine. And then, I’ll tell you something. My mother’s inclined to favor Beauvisage, who shuts her eyes with galantine and never comes to the house without a chitterling eight inches long. Mother’s crazy over chitterlings, and she’d like to have me marry the pork man, so that she could always have a pig’s pudding on hand. But I have always refused to hear with that ear, and since then they all look crosswise at me at home. So they’ll lay the quarrel and the whole row on my shoulders. Oh! mon Dieu! I shall be beaten, I am sure!”

“Poor Nicette! I promise you that I will speak to your mother in your behalf.”

“Oh! I beg you to! You see, she’s quite capable of not letting me in, and making me spend the night in the street! That miserable Beauvisage! he’s the cause of it all! I’d rather jump into the river than be his wife!”

“Can you say as much about Finemouche?”

“Yes, monsieur; I want a husband to my taste, and I don’t like any of those jokers.”

“Then you have no lover?”

“No, monsieur.”

“But, at your age, one ought to love.”

“Oh! I’m in no hurry. But we’re almost there, monsieur, we’re almost there. Ah! how my heart thumps!”

I felt that she was really trembling, and, to encourage her, I took one of her hands and pressed it. She made no resistance, she was thinking of nothing but her mother.

At last we reached Rue Sainte-Marguerite; Nicette dared not go any farther.

“There’s the place, monsieur,” she said; “that house next to the porte cochère.”

“Well, let us go there.”

“Oh! wait just a minute, till I can breathe!”

“Why are you so frightened? Am I not here?”

“Pardine! perhaps mother won’t even let you in!”

“We will make her listen to reason.”

“That will be hard.”

“Your sister is more to blame than you.”

“Yes, but she’s fond of my sister, and she don’t like me.”

“Well, we haven’t come all this distance not to try our luck.”

“That is true, monsieur. Come on, let’s go to the house.”

We arrived in front of Madame Jérôme’s shop; I had learned from Nicette that that was her mother’s name. Everything was tightly closed and perfectly still; no light could be seen inside the house.

“Does your mother sleep in the shop?”

“Yes, monsieur; at the back.”

“We must knock.”

“Oh! if only my sister hasn’t got home!”

“Let’s knock, in any event.”

I knocked, for Nicette had not the requisite courage; there was no reply.

“She sleeps very soundly,” I said to the girl.

“Oh, no, monsieur! that means that she don’t intend to let me in.”

“Parbleu! she’ll have to answer.”

I knocked again; we heard a movement inside, then someone approached the door, and a hoarse voice demanded:

“Who’s that knocking at this time of night?”

“It’s me, mother.”

“Ah! it’s you, is it, you shameless hussy! and you think I’ll let you in after midnight, when you’ve been setting men to fighting and turning a whole quarter upside down! Off with you this minute, and don’t ever let me see you again!”

“Mother! please let me in; my sister has deceived you.”

“No, no; I know the whole story. You’re a cursed little pig-headed fool! Ah! you don’t choose to be a pork man’s wife, don’t you? All right! go and walk the streets; we’ll see if you have pig’s pudding to eat every day!”

Nicette wept. I thought that it was time for me to intervene in the quarrel.

“Madame,” I called through the door, in a voice which I tried to make imposing, “your daughter has done no wrong; you are scolding her most unjustly; and if you leave her in the street, you will expose her to the risk of doing what you will regret.”

I waited for a reply; none was forthcoming, but I heard someone removing the iron bars, as if to open the shop. I went up to Nicette.

“You see,” said I, “my voice and my remonstrance have produced some effect. I was certain that I could pacify your mother. Come, dry your tears; she is coming, and I promise you that I will make her listen to reason, and that she won’t leave you to sleep in the street.”

Nicette listened, but she still doubted my ability to obtain her pardon. Meanwhile, the noise continued, and the door did, in fact, open. Madame Jérôme appeared on the threshold, wearing a dressing jacket and a nightcap. I stepped forward to intercede for the girl, who dared not stir; I was about to begin a sentence which I thought well adapted to touch a mother’s heart, but Madame Jérôme did not give me time.

“So you’re the man,” she cried, “who brings this boldface home, and undertakes to preach to me and to teach me how to manage my daughters! Take that to pay you for your trouble!”

As she spoke, the fruit seller dealt me a buffet that sent me reeling toward the other side of the street; then she drew back into her shop and slammed the door in our faces.

For five minutes I did not say a word to Nicette. Madame Jérôme’s blow had cooled my zeal in the girl’s cause very materially. I could not forbear reflecting upon the various events of the evening, and I seemed to detect therein a fatality which made me pay dearly for all my attempts at seduction.

For following a working girl, the tip of whose finger I had not been allowed to squeeze, I had been spattered with filth on Rue des Rosiers; for playing the gallant and making myself agreeable to a petite-maîtresse who bestowed divers exceedingly soft glances upon me, I had fallen in with an infernal cab driver, who had driven me to a strange quarter of the city, a long way from my own home; and lastly, for consenting to act as the protector of a young flower girl, whom I undertook to reconcile with her mother, I had received a well-aimed blow on the head. This last catastrophe seemed to me rank injustice on the part of Providence; for to take Nicette home to Madame Jérôme was a very kind action. What nonsense it is to talk about a benefaction never being wasted! But my cheek began to burn less hotly, and my ill humor became less pronounced. It was not Nicette’s fault that I had received that blow. I determined to make the best of my predicament and to console the poor child, whose distress was much augmented by this last accident.

“You are right, Nicette; your mother is very unkind.”

“Oh, yes, monsieur! What did I tell you? I am awful sorry for what happened to you; but if you hadn’t been there, I should have been beaten much worse than that.”

“In that case, it is clear that all is for the best.”

“My mother’s very quick!”

“That is true.”

“She has a light hand.”

“I found it rather heavy!”

“She cuffs me for a yes or a no; but it’s worse than ever, since I refused Beauvisage. Ah! I am very unhappy! It wouldn’t take much to make me jump into the Canal de l’Ourcq.”

“Come, come, be calm; the most urgent thing now is to find out where you can go to pass the night, as your mother really refuses to admit you. Have you any relations in this quarter?”

“Mon Dieu! no, not a soul; I have an aunt in Faubourg Saint-Denis; but she wouldn’t take me in—she’d be too much afraid of having a row with my mother.”

“Madame Jérôme is a general terror, I see.”

“Alas! yes.”

“Where will you sleep, then?”

“At your house, monsieur, with your permission; or else in the street.”

There was in Nicette’s suggestion such childlike innocence, or such shameless effrontery, that I could not restrain a start of surprise. It is difficult to believe in the innocence and naïveté of a flower girl. And yet, in her language there was something so sincere, so persuasive; and on the other hand, her eyes, whose expression was so soft and tender when they were not bathed in tears, her little retroussé nose, the way in which she had seized my arm, and, lastly, this barefaced proposal to pass the night in a young man’s apartment—all these things threw my mind into a state of uncertainty to which I tried in vain to put an end.

However, I was obliged to make up my mind. Nicette was gazing at me, awaiting my answer; her eyes implored me. My heart was weak.

“Come with me,” I said at last.

“Ah! monsieur, how good you are! how I thank you!”

Again she took possession of my arm, and we started for Rue Saint-Florentin. This time we made the journey in silence. I was musing upon the singularity of the adventure that had happened to me. The idea of my taking a street corner huckster home with me, to sleep in my rooms! And remember, reader, that I lived on Rue Saint-Florentin, near the Tuileries; you will divine, from that detail, that I was something of a swell, but a swell who followed grisettes. Oh! it was simply as a pastime. I was not in the least conceited, I beg you to believe; and if an impulse which I could not control drew me constantly toward the fair sex, and led me to overlook rank and social station, I may say with Boileau:

But I was not one of those persons, either, who defy all the proprieties; I did not wish to be looked upon, in the house in which I lived, as a man who consorted with the first woman he chanced to meet; and in that house, as everywhere, there were malicious tongues! I had, in particular, a certain neighbor. Ah!——

It was necessary, therefore, to keep Nicette out of sight. I hoped that that would be an easy matter, so far as going in was concerned. It was at least one o’clock in the morning, and my concierge would be in bed; when that was the case, if anyone knocked, she simply inquired, from her bed: “Who’s that?” and then pulled the cord, without disturbing herself further. So that Nicette could go up to my room unseen. But as to her going away the next day! Madame Dupont, my concierge, was inquisitive and talkative; she was like all concierges—I need say no more. The whole household would hear of the adventure; I should be unmercifully laughed at; it would be known in society. It was most embarrassing; but I could not leave Nicette in the street. Poor child! the watch would find her and take her to the police station, as a vagrant! And I honestly believed that she was a respectable girl; I almost believed that she was innocent; however, that would appear in due time.

We crossed the bridges, followed the quays, and at last drew near our destination. Nicette did not walk so rapidly as at first; she was tired out by her evening’s work; and I—well, I leave it to you to guess!

“Here we are!” I said at last.

“I’m glad of it; for I’m awful tired.”

“And I, too, I assure you. I must knock.”

“Oh! what a beautiful street! and what a fine house!”

“You mustn’t make any noise when we go upstairs, Nicette; you mustn’t speak!”

“No, monsieur, never fear; I don’t want to wake anybody up.”

“Sh! The door is open.”

Madame Dupont asked who was there; I replied, and we entered the house; the hall light was out and it was very dark; that was what I wanted.

“Give me your hand,” I whispered to Nicette, “and let me lead you; but, above all things, no noise.”

“All right, monsieur.”

I led her to the staircase, which we ascended as softly as possible. I wished with all my heart that we were safely in my rooms. If anyone should open a door, I could not conceal Nicette; I had not even a cloak to throw over her, for it was summer.

I lived on the fourth floor; to obtain a desirable bachelor’s apartment on Rue Saint-Florentin, one had to pay a dear price, even if it were very high. On the same landing with me lived a curious mortal of some thirty-six to forty years, whose face would have been insignificant but for the fact that his absurd airs and pretensions made it comical. He was of medium height, and strove to assume an agile and sprightly gait and bearing, despite an embonpoint which became more pronounced every day. He had four thousand francs a year, which left him free to devote himself to the business of other people. Moreover, he was poet, painter, musician; combining all the talents, as he said and believed, but in reality a butt for the ridicule of both men and women, especially the latter; but he insinuated himself everywhere, none the less, attended every party, every ball, every concert; because in society everybody is popular who arouses laughter, whether it be by his wit or by his absurdities.

We had just arrived at my landing, when Monsieur Raymond suddenly opened his door and appeared before us in his shirt and cotton nightcap, with a candle in one hand, and a key in the other.

I did not know whether to step forward or to turn back. Monsieur Raymond stared with all his eyes, and Nicette laughed aloud.

I was determined that he should not, at all events, have time to scrutinize the girl; I fumbled hastily in my pocket for my key, but it was entangled in my handkerchief; I could not get it out, I could not find the lock; the more I tried to hurry, the less I succeeded; it seemed that the devil was taking a hand!

Monsieur Raymond, observing my embarrassment, walked toward me with a mischievous smile and held his light under my nose, saying:

“Allow me to give you some light, neighbor; you can’t see, you are at one side of the lock.”

I would gladly have given him the blow that Madame Jérôme had given me! but I realized that I must restrain myself; so I thanked him, unlocked my door, and entered, pushing Nicette before me. I closed the door, paying no heed to Monsieur Raymond’s offer to light my candle for me.

But suddenly an idea came into my mind; I took a candle, opened my door again, and ran after Raymond, seizing him by his shirt just as he was entering a certain place. I put my finger to my lips, with a mysterious air.

“What’s the matter?” queried Raymond, extricating his shirt from my hand.

“Don’t mention the fact that you saw Agathe with me to-night.”

“A—Agathe! What do you say? Why, you are joking!”

“We have just come from a masquerade; she disguised herself for it, and——”

“Do you mean to say that there are masquerade balls in July?”

“There are if anyone chooses to give one; this was for somebody’s birthday.”

“But that girl——”

“She is well disguised, isn’t she? I’ll bet that you didn’t recognize her at the first glance. The costume—the rouge—they change one’s whole appearance.”

“Faith! I confess that I didn’t see even the slightest resemblance.”

“I rely on your discretion. To-morrow I will tell you what my motive is; you will laugh with me at the adventure. Au revoir, neighbor; good-night! Allow me to light my candle, now.”

“Much pleasure to you, Monsieur Dorsan!”

I left Raymond and returned to my room. My neighbor was not fully persuaded that it was Agathe whom he had seen; but I had at least, by my stratagem, reserved for myself an answer to his gossip; and if he should talk, I could easily persuade people that he was asleep and had not seen things as they were.

“But,” you will say, “by that falsehood you destroyed another woman’s reputation. Who is this Agathe whom you put forward so inconsiderately?”

This Agathe is my last mistress, with whom I had broken only a short time before; she is a milliner, very lively, very alluring, and very wanton! She had sometimes done me the honor to come to me to ask hospitality for the night; my neighbor had often seen her going in and out of my room, so that once more or less would do her no harm. Her reputation was in no danger, as you see.

Now that I have told you about Mademoiselle Agathe, with whom Monsieur Raymond did not know that I had fallen out, not being in my confidence, I return to Nicette, who is in my apartment, waiting for me. It was half-past one in the morning; but there is time for a great deal between that hour and daybreak! My heart beat fast! Faith! I had no idea what the night would bring to pass.

“What a funny man that is!” said Nicette, as I entered the room with a light. “When I saw that figure, in his shirt, that neckerchief tied with a lover’s knot, that big nose, and those surprised eyes, I couldn’t keep from laughing.”

“I must confess, Mademoiselle Nicette, that you cause me a lot of trouble!”

“Do I, monsieur? Oh! I am so sorry!”

“But here we are in my rooms at last, God be praised! I don’t quite know, though, how you are to go out!”

“Pardine! through the door, as I came.”

“That’s easy for you to say! However, we will see, when to-morrow comes.”

Nicette looked about her. She examined my apartment, my furniture; she followed me into each room; I had only three, by the way: a small reception room, a bedroom, and a study where I worked, or read, or played the piano, or did whatever else I chose.

“Sit down and rest,” I said.

“Oh! in a moment, monsieur; you see——”

She glanced at my couch and my easy-chairs; she seemed to be afraid to go near them. I could not help smiling at her embarrassment.

“Doesn’t the apartment please you?” I inquired.

“Oh! yes, indeed, monsieur! but it’s all so fine and so shiny! I’m afraid of spoiling something.”

“You need not be afraid.”

I led her to the couch, and almost forced her to sit down by my side.

“I am alone, you see, Nicette; you have come to a bachelor’s quarters.”

“Oh! I don’t care about that, monsieur; at any rate, I didn’t have any choice.”

“Then you’re not afraid to pass the night with me?”

“No, monsieur; I see that you’re an honorable man, and that I needn’t be afraid of anything in your rooms.”

“Oho! she sees that I am an honorable man!” said I to myself; “in that case, I must have a very captivating countenance. However, I am not ill-looking; some women say that I am rather handsome; and this girl isn’t afraid to pass the night with a good-looking bachelor! Perhaps she thinks me ugly.”

These reflections annoyed me; while making them, I looked at Nicette more closely than I had hitherto been able to do. She was really very good-looking; a face at once piquant and sweet, and with some character—absolutely unlike what we ordinarily find in a flower girl: she had the freshness and charm of her flowers, and she was the daughter of a fruit peddler, of Mother Jérôme! There are such odd contrasts in nature; however, I could but acknowledge that chance had been very favorable to me this time. I began to be quite reconciled to my evening’s entertainment; I forgot the grisette and the petite-maîtresse, to think solely of the charming face at my side.

As I gazed at the girl, I had moved nearer to her; I softly passed my arm about her waist; and the more favorable the examination, the more tightly I pressed the red gown.

Nicette did not speak, but she seemed agitated; her bosom rose and fell more frequently, her respiration became shorter; she kept her eyes on the floor. Suddenly she extricated herself from my embrace, rose, and asked me, in a trembling voice, where she was to pass the night.

That question embarrassed me; I admit that I had not yet thought of that. I glanced at Nicette; her lovely eyes were still fastened on the floor. Was she afraid to meet mine? Did she love me already? and—— Nonsense! that infernal self-esteem of mine was off at a gallop!

“We have time enough to think about that, Nicette. Do you feel sleepy?”

“Oh, no! it ain’t that, monsieur.”

“Ah! so there’s another reason, is there?”

“I don’t want to be in your way; you told me you was tired, too.”

“That has all passed away; I have forgotten it.”

“Never mind, monsieur; show me where I can pass the night. I’ll go into one of the other rooms. I shall be very comfortable on a chair, and——”

“Pass the night on a chair! Nonsense! you mustn’t think of such a thing!”

“Oh, yes! I ain’t hard to suit, monsieur.”

“No matter; I shan’t consent to that. But sit down, Nicette, there’s no hurry now. Come and sit down. Are you afraid to sit beside me?”

“No, monsieur.”

But she took her seat at the other end of the couch. Her blushing face and her confusion betrayed a part of her sensations. I myself was embarrassed—think of it! with a flower girl! Indeed, it was just because she was a flower girl that I didn’t know where to begin. I give you my word, reader, that I should have made much more rapid progress with a grande dame or a grisette.

“Do you know, Nicette, that you are charming?”

“I have been told so, monsieur.”

“You must have many men making love to you?”

“Oh! there’s some that try to fool me when they come to buy flowers of me; but I don’t listen to ’em.”

“Why do you think that they are trying to fool you?”

“Oh! because they’re swells—like you.”

“So, if I should mention the word love to you, you would think——”

“That you was making fun of me. Pardi! that’s plain enough!”

That beginning was not of good augury. No matter, I continued the attack, moving gradually nearer the girl.

“I swear to you, Nicette, that I never make fun of anyone!”

“Besides, you are quite pretty enough to arouse a genuine passion.”

“Yes, a passion of a fortnight! Oh! I ain’t to be caught in that trap.”

“On my honor, you are too pretty for a flower girl.”

“Bah! you are joking.”

“If you chose, Nicette, you could find something better to do than that.”

“No, monsieur, no; I don’t want to sell anything but bouquets. Oh! I ain’t vain. I refused Beauvisage, who’s got money, and who’d have given me calico dresses, caps à la glaneuse, and gilt chains; but all those things didn’t tempt me. When I don’t like a person, nothing can make me change my mind.”

She was not covetous; so that it was necessary to win her regard in order to obtain anything from her. I determined to win her regard. But I have this disadvantage when I try to make myself agreeable: I never know what I am saying; that was why I sat for ten minutes without speaking a word to Nicette, contenting myself with frequent profound sighs and an occasional cough, to revive the conversation. But Nicette was very innocent, or perhaps she meant to laugh at me when she said with great sang-froid:

“Have you got a bad cold, monsieur?”

I blushed at my idiocy; the idea of being so doltish and timid with a flower seller! Really, I hardly recognized myself.

And the better to recognize myself, I put my arms about Nicette and tried to draw her into my lap.

“Let go of me, monsieur; let go, I beg you!”

“Why, what harm are we doing, Nicette?”

“I don’t want you to squeeze me so tight.”

“One kiss, and I’ll let you go.”

“Just one, all right.”

Her consent was necessary, for she was very well able to defend herself; she was strong and could make a skilful use of her hands and knees; and as I was not accustomed to contests of that sort, in which our society ladies give us little practice, I began to think that I should find it difficult to triumph over the girl.

She gave me permission to kiss her, and I made the most of it; trusting in my promise, she allowed me to take that coveted kiss, and offered me her fresh, rosy cheek, still graced with the down of youth and innocence.

But I desired a still greater privilege; I longed to steal from a lovely pair of lips a far sweeter kiss. Nicette tried, but too late, to prevent me. I took one, I took a thousand. Ah! how sweet were those kisses that I imprinted on Nicette’s lips! Saint-Preux found Julie’s bitter; but I have never detected a trace of bitterness in a pretty woman’s kisses; to be sure, I am no Saint-Preux, thank heaven!

A consuming flame coursed through my veins. Nicette shared my emotion; I could tell by the expression of her eyes, by the quivering of her whole frame. I sought to take advantage of her confusion to venture still further; but she repulsed me, she tore herself from my arms, rushed to the door, and was already on the landing, when I overtook her and caught her by her skirt.

“Where in heaven’s name are you going, Nicette?”

“I am going away, monsieur.”

“What’s that?”

“Yes, monsieur, I am going away; I see now that I mustn’t pass the night here in your rooms; I wouldn’t have believed that you’d take advantage of my trouble to—— But since I made a mistake, I’m going away.”

“Stop, for heaven’s sake! Where would you go?”

“Oh! I don’t know about that; but it don’t make any difference! I see that I’d be safer in the street than alone here with you.”

I felt that I deserved that reproach. The girl was virtuous; she had placed herself under my protection without distrust; she had asked me for hospitality, and I was about to take advantage of her helpless plight, to seduce her! That was contemptible behavior. But I may say, in my own justification, that I did not know Nicette, and that, for all the artless simplicity of her language, a young girl who suggests to a man that she pass the night under his roof certainly lays herself open to suspicion, especially in Paris, where innocent young maids are so rare.

She still held the door ajar, and I did not relax my grasp of her skirt. I looked in her face, and saw great tears rolling down her cheeks. Poor child! it was I who caused them to fall! She seemed prettier to me than ever; I was tempted to throw myself at her feet and beg her to forgive me. But what! I, on my knees before a street peddler! Do not be alarmed: I did not offend the proprieties to that extent.

“I beg you to remain, Nicette,” I said, at last.

“No, monsieur; I made a mistake about you; I must go.”

“Listen to me; in the first place, you can’t go away from the house alone; at this time of night the concierge opens the door only to those who give their names.”

“Oh! but I remember your name; it’s Dorsan.”

“It isn’t enough to give my name; she would know that it wasn’t my voice.”

“All right; then I’ll stay in the courtyard till morning.”

“Excellent; everybody will see you; and think of the remarks and tittle-tattle of all the cooks of the quarter! It’s bad enough that that infernal Raymond should have seen you. Come back to my rooms, Nicette; I promise, yes, I swear, to behave myself and not to torment you.”

She hesitated; she looked into my face, and doubtless my eyes told her all that was taking place in my mind; for she closed the door of the landing, and smiled at me, saying:

“I believe you, and I’ll stay.”

In my joy I was going to kiss her again; but I checked myself, and I did well: oaths amount to so little!

“But, monsieur,” she said, “we can’t pass the night sitting in your big easy-chair.”

She was quite right; that would have been too dangerous.

“You will sleep in my bed,” I replied, “and I will pass the night on the sofa in my study. No objections, mademoiselle; I insist upon it. You will be at liberty to double-lock my study door; you can go to sleep without the slightest fear. Does that suit you?”

“Yes, monsieur.”

We went back into my bedroom; I lighted another candle, and carried the couch into my study, with Nicette’s assistance. I confess that that operation was a painful one to me. However, it was done at last.

“Now you may go to bed and sleep in peace. Good-night, Nicette!”

I took my candle and retired to my study, closing the door behind me. There we were, in our respective quarters. I blew out the candle and threw myself on the couch. If only I could sleep; time passes so quickly then! And yet, we sleep about a third part of our lives! and we are always glad to plunge into that oblivion, albeit we stand in fear of death, which is simply a never-ending sleep, during which it is certain that one is not disturbed by bad dreams!

Sleep, indeed! In vain did I stretch myself out, and twist and turn in every direction. I could not sleep; it was impossible. I concluded to resign myself to the inevitable, and I began to recall the incidents of my extraordinary evening; I thought of Caroline, of the charming woman at the theatre, of that infernal cabman. I tried to put Nicette out of my thoughts; but she constantly returned; I strove in vain to banish her. The idea that she was close at hand, within a few feet of me, that only a thin partition separated me from her—that idea haunted me! When I thought that I might be beside her, that I might hold her in my arms and give her her first lessons in love and pleasure—then I lost my head, my blood boiled. Only Nicette’s consent was needed to make us happy, and she would not give it! To be sure, that same happiness might have results most embarrassing to her.

I had the fidgets in my legs. I rose and paced the floor, but very softly; perhaps she was asleep, and I would not wake her. Poor child! she had had trouble enough during the evening, and I was afraid that still greater trouble was in store for her; for if her mother persisted in her refusal to take her in, what would she do? Until that moment, I had not given a thought to her future.

But I had not heard the key turn in the lock; therefore, she had not locked herself in. That was strange; evidently she relied on my oath. What imprudence, to believe in a young man’s promises!

Was she asleep or not? that was what tormented me. For half an hour I stood close against the door, turning first one ear, then the other, and listening intently; but I could hear nothing. I looked through the keyhole; there was a light in the room; was it from caution, or forgetfulness?

But she had not locked the door. Ah! perhaps she had locked it without my hearing it. It was very easy to satisfy myself on that point. I turned the knob very gently, and the door opened. I stopped, fearing that I had made a noise. But I heard nothing. If I could see her for a moment asleep, see her in bed—for there, and only there can one judge a woman’s beauty fairly. I leaned forward; the candle stood on the commode, at some little distance from the bed. I stepped into the room, holding my breath, and stood by her side. She was not undressed; I might have guessed as much. I turned to walk away. Ah! those miserable shoes! they squeaked, and Nicette awoke. I determined to change my shoemaker.

“Do you want anything, monsieur?” she asked.

“No; that is to say, yes, I—I was looking for a book; but I have found it.”

I returned quickly to my study, feeling that I must have cut a sorry figure. The door was closed, and I was not tempted to open it again. Ah! how long that night seemed to me! The day came at last!

It was long after daybreak. People were already going and coming in the house, and I had not yet ventured to wake Nicette. She was sleeping so soundly! and the preceding day had been a day of tempest, after which rest was essential. But I heard a movement at last; she rose, opened the door, and came toward me, smiling.

“Monsieur, will you allow me to kiss you?”

I understood: that was my reward for my continence during the night, and it was well worth it. She kissed me with evident pleasure, and I began to feel the enjoyment that one is likely to feel when one has no occasion for self-reproach.

“Now, Nicette, let us talk seriously; but, no, let us breakfast first of all; we can talk quite as well at table. You must feel the need of something to eat, do you not?”

“Yes, monsieur, I should like some breakfast right well.”

“I always keep something on hand for unexpected guests.”

“Tell me where everything is, monsieur, and I’ll set the table.”

“On the sideboard yonder, and in the drawers.”

“All right, all right!”

She ran to fetch what we required. In two minutes the table was set. I admired Nicette’s grace and activity; a little maid-servant like that, I thought, would suit me infinitely better than my concierge, Madame Dupont, who took care of my rooms. But, apropos of Madame Dupont, suppose she should appear? We had time enough, however; for it was only seven o’clock, and the concierge, knowing that I was a little inclined to be lazy, never came up before eight. So that we could breakfast at our ease.

“Let us talk a little, Nicette. I am interested in your future; you cannot doubt that.”

“You have proved it, monsieur.”

“What are you going to do when you leave me?”

“Go back to my mother.”

“That is quite right; but suppose she still refuses to let you in?”

“I will try to find work; I will go out to service, if I must; perhaps I shall be able to get in somewhere.”

“Undoubtedly; but who can say what sort of people you will encounter, and what hands you will fall into? Young and pretty as you are, you will find it harder than others might to get a suitable place, if, as I assume, you mean to remain virtuous.”

“Oh! indeed I do mean to remain virtuous, monsieur.”

“I know what men are; they are almost all libertines; marriage puts no curb on their passions. Wherever you take service, your masters will make you some unequivocal proposals, and will maltreat you if you reject them.”

“Then I will leave the house; I’ll hire myself out to a single lady.”

“Old maids are exacting, and keep their young servants in close confinement, for fear that they may walk the streets and make acquaintances. Young women receive much company, and will set you a dangerous example.”

“How good you talk this morning!”

“Don’t wonder at that; a drunkard is a connoisseur in wine, a welcher in horses, a painter in pictures, a libertine in methods of seduction. For the very reason that I am not virtuous, I am better able than another to warn you of the risks you are about to run. Experience teaches. You did not yield to me, and I desire to preserve you for the future. Don’t be grateful to me for it; very likely, it is simply a matter of self-esteem on my part, for I feel that it would be distressing to me to see the profanation of a flower that I have failed to pluck. You understand me, don’t you, Nicette?”

“Yes, yes, monsieur! I’m no prude, and I know what you mean! But don’t be afraid! How could I give another what I refused you?”

She said this with evident feeling and sincerity. Clearly she liked me; I could not doubt it; she was all the more praiseworthy for having resisted me.

“After all, my dear girl, I don’t see why you shouldn’t continue to sell flowers; it is better suited to you than domestic service.”

“That is true, monsieur, but——”

“I understand you. Here, Nicette, take this purse; you may accept it without a blush, for it is not the price of your dishonor. I am simply doing you a favor, lending you a little money, if you like that better.”

“Oh! monsieur, money—from a young man! What will people think of that?”

“You must not say from whom you got it.”

“When a girl suddenly has money in her possession, people think, they imagine that——”

“Let the gossips chatter, and force them to hold their tongues by the way you behave.”

“My mother——”

“A mother who refuses to support her child has no right to demand an account of her actions.”

“But this purse—you are giving me too much, monsieur.”

“The purse contains only three hundred francs; I won it two days ago at écarté. Really, Nicette, if you knew how easily money is lost at cards, you would be less grateful to me for this trifle.”

“A trifle! three hundred francs! enough to set me up in business! Why, monsieur, it’s a treasure!”

“Yes, to you who know the full value of money, and use it judiciously. But things are valuable only so long as they are in their proper place.”

“All this means, I suppose, that you are very rich?”

“It means that, having been brought up in affluence, accustomed to gratify all my whims, I am not familiar enough with the value of money. This three hundred francs that I offer you, I should probably lose at cards without a pang; so take the money, Nicette; you can give it back to me, if the day ever comes when I need it.”

“Oh, yes! whenever you want it, monsieur; everything I have will always be at your service.”

“I don’t doubt it, my dear friend; so that business is settled.”

“Yes, monsieur; if my mother sends me away, I’ll hire a small room, I’ll buy flowers; I’ll be saving and orderly, and perhaps some day I’ll get where I can have a nice little shop of my own.”

“Then you will marry according to your taste, and you’ll be happy.”

“Perhaps so! but let’s not talk about that, monsieur.”

“Well! time flies; it’s nearly eight o’clock, and you must go, Nicette.”

“Yes, monsieur, that is true; whenever you say the word. But I—is——”

“What do you want to say?”

“Shan’t I see you again?”

“Yes, indeed; I hope to see you often. If you move to another quarter, you must leave your new address with my concierge.”

“Very well, monsieur; I won’t fail.”

The child was in evident distress; she turned her face away to conceal her tears. Could it be that she was sorry to leave me? What nonsense! We had known each other only since the night before! And yet, I too was unhappy at parting from her.

She was certain to meet one or more servants on the stairs; but what was she to do? there was no other way out. She promised to go down very rapidly, and to hurry under the porte cochère.

I kissed her affectionately—too affectionately for a man who had given her three hundred francs; it was too much like taking compensation for the gift.

I opened the door leading to the landing, and stood aside to let Nicette go out first, when a roar of laughter made me look up. That fiendish Raymond’s door was open, and he stood inside with a young woman; that young woman was Agathe!

It was a contemptible trick. I recognized Raymond’s prying curiosity and Agathe’s spirit of mischief. They were on the watch for me, no doubt; possibly they had been on sentry-go since daybreak. But how did it happen that Agathe was there? She had never spoken to Raymond. I swore that he should pay me for his perfidy.

Nicette looked at me, trying to read in my eyes whether she should go forward or back. It was useless to pretend any longer; perhaps, indeed, if there were any further delay, Monsieur Raymond would succeed in collecting a large part of the household on my landing. So I pushed Nicette toward the stairs.

“Adieu, Monsieur Dorsan!” she said sadly.

“Adieu, adieu, my child! I hope that your mother—— I will see—you shall hear—perhaps we may—adieu!”

I had no idea what I was saying; anger and vexation impeded my utterance. But Nicette, who was moved by but one sentiment,—regret at leaving me,—wiped the tears from her eyes with a corner of her apron.

“Ha! ha! this is really sentimental!” laughed Mademoiselle Agathe, as she watched the girl go downstairs; “what! tears and sighs! Ha! ha! it’s enough to make one die of laughing! But I should be much obliged to you, monsieur, if you would tell me how it happened that I was at a ball with you last night, and disguised, without knowing anything about it. Well! why don’t you speak? don’t you hear me?”

My attention was engrossed by another object. My eyes were fastened on my neighbor, and my steadfast gaze evidently embarrassed him; for, in a moment, I saw that he turned as red as fire; he began to shift about in his confusion, tried to smile, and at last returned to his own room, taking care to lock the door.

“Ah! Monsieur Raymond, I owe you one for this! we shall meet again!” I said, walking toward his door. Then I turned to answer Mademoiselle Agathe, but she had entered my apartment; and as she was perfectly familiar with the locality, I found her in my little study, nonchalantly reclining on the sofa.

“Do tell me, Eugène, what all this means? Mon Dieu! how things are changed about! the couch in the study; the bed partly tumbled; the remains of a breakfast. What happened here last night?”

“Nothing, I assure you.”

“Oh! nothing out of the ordinary course, I understand that. But this couch puzzles me. Tell me about it, Eugène, my little Eugène. Because you are no longer my lover is no reason why we shouldn’t be friends.”

You are aware, reader, that Mademoiselle Agathe is the milliner with whom I had fallen out because I discovered that she was unfaithful to me. In fact, it was my vexation on her account that had led me to indulge in those melancholy reflections during my stroll along the boulevard on the preceding evening. But since then my susceptible heart had experienced so many new sensations, that the memory of Agathe’s treachery had vanished altogether; I had ceased to regret her, consequently I was no longer angry with her. I realized that she was justified in joking me about my serious air, which was not at all consistent with our former liaison, and which might have led one to think that I expected to find a Penelope in a young milliner. So I assumed a more cheerful demeanor, and questioned her in my turn.

“How did you happen to be there on my landing, talking with Raymond, whom you could never endure?”

“But this couch—this couch here in the study?”

“You shall know all about it, but answer me first.”

“Oh! I’ve no objection; I went into the country yesterday with Gerville—you know, the young government clerk who lives on the floor below.”

“Yes, my successor, in fact.”

“Your successor, call him so. We returned late; I was very tired, and——”

“You passed the night with him; that’s a matter of course, and perfectly natural, in my opinion. Well?”

“Why, I had to go away this morning. At half-past six, I crept softly downstairs and was just passing through the porte cochère, when I saw Raymond standing guard at the corner. He scrutinized me, and smiled slyly.—‘On my word,’ he said, ‘I didn’t believe it was you; you were perfectly disguised; the fishwoman’s costume is very becoming to you, and yet it changes you amazingly. I’d have sworn that Monsieur Dorsan was lying to me.’—I listened, without understanding a word; but your name and what he said aroused my curiosity. I suspected some mistake, so I forced Raymond to tell me all he knew; I haven’t stopped laughing at it yet. Raymond was delighted when he found out that it wasn’t I who was with you. I asked him if he was certain that your new victim was still in the house. He said he was; for he had passed most of the night on the landing, and had gone on duty at the porte cochère at daybreak. So I came up with him, to make the tableau more interesting; and we waited at least an hour, until it was your good pleasure to open your door. We would have stayed there till night, I assure you, rather than not satisfy our mutual curiosity.”

“Gad! what a fellow that Raymond is! An old woman couldn’t have done better.”

“Well, I’ve told my story; now it’s your turn.”

“What do you want me to tell you? You saw a girl leave my rooms, eh?”

“Yes, she was very pretty; a face that takes your eye; rather a large mouth. But that costume! What, Monsieur Eugène! you, a dandy of dandies, caught by a round cap! Why, I no longer recognize you!”

“For what I propose to do, mademoiselle, the question of cap or hat is of no consequence at all.”

“Of course, you don’t propose to do anything, because you have done enough.”

“You are mistaken, Agathe. That is an honest, virtuous girl; she is nothing to me, and never will be.”

“What’s that? Oh! it’s as plain as a pikestaff: she came here to sleep, so as not to be afraid of the dark; that’s all!—

“I realize that appearances are against us; and yet nothing can be more true than what I tell you. The explanation as to the couch being in the study is that she slept in my bedroom, and I slept here.”

“For ten minutes, very likely; but after that you joined her.”

“No; I swear that I did not.”

“You’d never have been donkey enough to stay here.”

“I understand that, in your eyes, virtue and innocence are the merest folly.”

“Ah! you are not polite, monsieur. But as I have never known you to be either virtuous or innocent, I may be permitted to express surprise at your virtuous qualities, which are entirely unfamiliar to me.”

“I am not trying to make myself out any better than I am, and I confess to you frankly that I attempted to triumph over this girl; but her resistance was so natural, her tears so genuine, her entreaties so touching, that I was really deeply moved and almost repented of what I had tried to do.”

“That is magnificent; and I presume that the virtuous and innocent orange girl came to your rooms in order that her resistance might be the better appreciated.—Ha! ha! what a fairy tale!”

“You may believe what you choose. It is none the less true that Nicette is virtuous and that she isn’t an orange girl.”

“Oh! pardon me, monsieur, if I have unintentionally slighted your charmer. Mademoiselle Nicette probably sells herring at the Marché des Innocents?”

“No, mademoiselle; she sells nothing but flowers.”

“Flowers! Why, that is superb! Ah! so she’s a flower girl! I am no longer surprised at your consideration for her.”

“She certainly deserves more consideration than many women who wear fashionable bonnets.”

“Or who make them, eh?”

“The argument is even stronger as to them.”

“Monsieur is vexed because I venture to doubt the virtuous morals of a girl who comes, very innocently no doubt, to sleep with a young man, who has himself turned Cato in twenty-four hours! Look you, Eugène, I don’t care what you say, it isn’t possible.”

“I shall say nothing more, because I attach no value to your opinion.”

“Again! No matter, let’s make peace; and I will believe, if it will give you pleasure, that your friend was the Maid of Orleans.”