Dodd, Mead & Company New York 1960

© by Eddy Kjelgaard, 1959.

Second printing

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher

The general situation and many of the events described in this book are based upon historical facts. However, the fictional characters are wholly imaginative: they do not portray and are not intended to portray any actual persons.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 59-6197

Printed in the United States of America by Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., Binghamton, N. Y.

| 1. | ALI FINDS THE DALUL | 1 |

| 2. | FUGITIVE | 21 |

| 3. | AMBUSH | 38 |

| 4. | THE HADJ | 52 |

| 5. | THE UNPARDONABLE SIN | 64 |

| 6. | THE STRANGE SHIP | 78 |

| 7. | ANOTHER PILGRIMAGE | 94 |

| 8. | TROUBLE | 105 |

| 9. | LIEUTENANT BEALE | 120 |

| 10. | THE EXPEDITION | 133 |

| 11. | THE WILDERNESS | 145 |

| 12. | THE ROAD | 158 |

| 13. | REUNION | 174 |

The first gray light of very early morning was just starting to thin the black night when Ali opened his eyes. He came fully awake, with no lingering period that was part sleep and part wakefulness, but he kept exactly the same position he had maintained while slumbering. Until he knew just what lay about him, he must not move at all.

Motion, even the faintest stir and even in this dim light, was sure to attract the eye of whoever might be near. In this Syrian desert, where only the reckless turned their backs to their own caravan companions, whoever might be near—or for that matter far—could be an enemy.

When Ali finally moved, it was to extend his right hand, very slowly and very stealthily, to the jeweled dagger that lay snugly sheathed beneath the patched and tattered robe that served him as burnous by day, and bed and bed covering by night. When his fingers curled around the hilt, he breathed more easily. Next to a camel—of course a dalul, or riding camel—a dagger was the finest and most practical of possessions, as well as the best of friends.

As for owning a dalul, Ali hadn't even hoped to get so much as a baggage camel for this journey. When it finally became apparent that the celestial rewards of a trip to Mecca would be augmented by certain practical advantages if he made his pilgrimage now, he had just enough silver to pay for the ihram, or ceremonial robe that he must don before setting foot in the Holy City. Even then, it had been necessary to provide Mustapha, that cheating dog of a tailor, with four silver coins—and two lead ones—and Mustapha had himself to thank for that! When Ali came to ask the price, it was five pieces of silver. When he returned to buy, it was six.

But the ihram, as well as the fifth silver coin which Mustapha might have had if he'd retained a proper respect for a bargain, were now safe beneath Ali's burnous. The dagger was a rare and beautiful thing. It had been the property of some swaggering desert chief who, while visiting Damascus, Ali's native city, had imprudently swaggered into a dark corner.

Though he frowned upon killing fellow humans for other than the most urgent reasons, and he disapproved completely of assassins who slew so they might rob, it never even occurred to Ali that he was obliged to do anything except disapprove. He knew the usual fate of swaggering desert chieftains who entered the wrong quarters of Damascus, and, when the inevitable happened, he did not spring to the rescue. That was not required by his code of self-preservation. So the assassin snatched his victim's purse and fled without any intervention. Ali got the dagger.

In the light of the journey he was undertaking, and the manner in which he was undertaking it, a dagger was infinitely more precious than the best-filled purse. Mecca was indeed a holy city, but of those who traveled the routes leading to it, not all confined themselves to holy thoughts and deeds. Many a pilgrim had had his throat slit for a trifle, or merely because some bandit felt the urge to practice throat slitting. A dagger smoothed one's path, and, as he waited now with his hand on the hilt of his protective weapon, Ali thought wryly that his present path was in sore need of smoothing.

He'd left Damascus two weeks ago, intending to offer his services, as camel driver, to the Amir of the nearby village of Sofad. He would then travel to Mozarib with his employer's caravan. The very fact that there would be force behind the group automatically meant that there would also be reasonable safety. Located three days' journey from Damascus, two from Sofad, Mozarib was the assembly point and starting place for the great Syrian Hadj, or pilgrimage. It went without saying that, if Ali tended to his camel driving and kept his dagger handy, he would go all the way to Mecca with the great Hadj, which often consisted of 5000 pilgrims and 25,000 camels.

Thus he had planned, but his plans had misfired.

He reached Sofad on the morning scheduled for departure, only to find that the Amir, at the last moment, had decided to make this first march toward Mozarib a cool one and had left the previous night. Hoping to catch up, but not unmindful of the perils that beset the way when he neared the camp of the Sofad pilgrims, Ali had decided that it would be prudent to reconnoiter first. It had indeed been prudent.

Peering down at the camp from a nest of boulders on a hillock, Ali was just in time to see the Amir and his fourteen men beheaded, in a most efficient fashion, by sword-wielding Druse tribesmen who'd taken the camp. Afterwards, the raiders had loaded everything except the stripped bodies of their victims on their own camels and departed.

It was a time for serious thinking, to which Ali had promptly devoted himself. Unfortunately, he failed also to think broadly, and the only conclusion he drew consisted of the fact that it was still possible for him to go on and join the Hadj. Camel drivers were always welcome. Sparing not a single thought to the idea that Druse raiders would rather kill than do anything else, Ali had almost been caught unawares by the one who had slipped hopefully back to see if he could find somebody else to behead. Ali had taken to his heels and, so far, he had proved that he was fleeter than his pursuer. Tenacious as any bloodhound, the Druse had stayed on his trail until yesterday morning. Now he was shaken. Ali knew that he was somewhere south of Damascus and, with any luck, might yet join the Hadj.

Help would not come amiss. Ali drank the last sip from his goatskin water flask, shifted his dagger just a little, so it would be ready to his hand should he have need of it, and made ready to address himself to the one unfailing Source of help.

Though he had no more water, there was an endless supply of sand. Good Moslems who could read and write had assured him that this statement appears in the Koran: "When ye rise up to prayer, wash your faces and your hands and your arms to the elbows, and wipe your heads and your feet to the ankles." Though it was commonly assumed that one would cleanse himself with water before daring to mention Allah's name, special provisions applied to special occasions. For those who had no water, sand was an acceptable substitute.

His ablutions performed, Ali faced toward Mecca, placed an open hand on either side of his face and intoned, "God is most great." Remaining in a standing position, he proceeded to the next phase of the prayer that all good Moslems must offer five times daily.

It was the recitation of the opening sura, or verse, of the Koran. Ali, who'd memorized the proper words, had not proceeded beyond, "In the name of the merciful and compassionate God. Praise belongs to God—" when he was interrupted by the roar of an enraged camel.

Ali halted abruptly, instantly and completely, forgetting the sacred rite in which he'd been absorbed and that had five more complete phases, each with prescribed gestures, before he might conclude it. When he finally remembered, he was a little troubled; Allah might conceivably frown upon whoever interrupted prayers to Him. But Ali remembered also that Allah is indulgent toward those who are at war, in danger, ill, or for other good reasons are unable to recite the proper prayers in the proper way at the prescribed times.

Surely a camel in trouble—and, among other things, the beast's roar told Ali that it was in trouble—was the finest of reasons for ignoring everything else. Not lightly had the camel been designated as Allah's greatest gift to mankind. To slight His gift would be to slight Him. His conscience clear on that point, Ali devoted himself to analyzing the various things he'd learned about when a camel roared in the distance.

The earliest recollection of Ali, who'd never known father or mother, was of his career as a rug vendor's apprentice in the bazaar of The Street Called Straight. His master worked him for as many hours as the boy could stay awake, beat him often and left him hungry when he was unable to steal food. But the life was not without compensations.

Though no longer enjoying the flourishing trade it had once known, Damascus sat squarely astride the main route between the vast reaches of Mohammedan Turkey and Mecca, the city that every good Moslem must visit at least once during his lifetime. The Turks came endlessly, and in numbers, and since it's only sensible to do a little trading, even when on a holy pilgrimage, when they reached Damascus, they stopped to trade at The Street Called Straight. But though the pilgrims were interesting, Ali found the camels that carried both the Turks and their goods infinitely more so.

He knew them all—plodding baggage beasts, two-humped bactrians, the hybrid offspring of bactrians and one-humped camels, and all the species and shades of species in between. But though he liked all camels, he saved his love for the dromedary, the heira, the hygin, riding camel, or, as Ali called them, the dalul.

Invariably ridden by proud men and never used for any purpose other than riding, they were a breed apart. Slighter and far more aristocratic than the baggage beasts, they could carry a rider one hundred miles between sunrise and sunset, satisfy themselves with a few handfuls of dates when the ride ended, and go without water for five days. Their pedigrees, in many instances longer than those of their riders, dated back to pre-Biblical history. The owner of a dalul considered such a possession only slightly less precious than his life.

It was when he became acquainted with the dalul that Ali invented his own mythical father. This parent was not a nameless vagabond, petty thief, or fly-by-night adventurer who never even knew he'd sired a son and wouldn't have cared if he had, but a renowned trainer of dalul. It was he who went to the camel pastures and chose the wild young stallions that were ready for breaking. Though they would kill any ordinary man who ventured near, Ali's father gentled them and taught them to accept the saddle and rein. Ali determined that he himself must go out with the camels and promptly ran away from his master.

Because he was too young to be of any imaginable use, the few caravan masters who condescended to look at him usually aimed a blow right after the look. For two years Ali was one of the numerous boy-vagabonds who infested the bazaars of Damascus. If such a life did not elevate the mind it could not help but sharpen the wits.

Then, just after his ninth birthday, Ali got his chance to go out with a caravan. It was a very small and very poor one, fewer than fifty camels, and the caravan master decided to take Ali only because he was a boy. As such, quite apart from the fact that he could safely be browbeaten, it was reasonable to assume that he had not had time to learn all the tricks of experienced drivers, the more talented among whom have been known to get rich, and leave the owners poor, on just one journey.

Apart from their uses and physical functions, which he learned so precisely that one glance enabled him to cite any camel's past history, age, present state of health, and what it would probably do next, Ali came to appreciate the true miracle of a camel. He was the one in ten thousand, the camel driver who knew everything the rest did—and much they did not—and who transcended that to understand clearly the nature of the camel itself. So fine was his touch and so complete the affinity between camels and himself, that even beasts thought hopelessly unmanageable responded to him.

Nine years old when he made his first trip, Ali had spent the past nine years on the caravan routes. He'd been to Baghdad, Istanbul, Tosya, Trebizond. He went where the camels went and never cared if it was two hundred miles or two thousand. But though every member of a caravan is entitled to trade for himself, and many a camel driver has become a caravan master or owner, Ali was as poor as on the day he started.

Partly responsible for this was his consuming passion for camels and his negligible interest in trading. Far more at fault was his origin. The men of the caravans knew him as Ali, and only Allah could know more about camels. To the merchants, who saw camels merely as the most convenient method for transporting goods, he remained the orphan waif of Damascus. They turned their backs upon one who had neither family nor prestige, who could point to no achievement other than an outstanding skill with camels. Now, camels were very convenient, but, as every merchant in a perfumed drawing room knew, they also smelled!

So Ali had a most compelling reason for deciding to undertake his pilgrimage at this time. After he'd been to Mecca, like all others who have completed the difficult and dangerous journey, he'd be entitled to add the prefix "Hadji" to his name. That alone would never make him the equal of the wealthy merchants who also had been to Mecca, but it would surely make him the superior of all who had not. And this was a vast number, since the life of a merchant is not necessarily conducive to physical achievement and the journey to Mecca is hard.

Now, in a desert wilderness, while on the way to Mecca, a camel had cried out to Ali, and he could not have helped responding, even if the camel had cried while he was at prayer in the masjid-al-haram, the Great Mosque of Mecca.

Its roar had already told Ali many things about the beast, including the exact direction he must take to find it and approximately how far he must go before locating it. The sound had had a certain timbre and quality that hinted of regal things and regal bearing, therefore it was not a baggage animal. However, neither did it have the awesome blast of a fully-grown dalul. It was not challenging another stallion to battle, but roaring in rage and defiance at something that it did not know how to fear.

Ali's hand slipped back to the hilt of his dagger. Unmindful of the hot little wind that had just arisen, and that would become hotter as the day grew longer, he started toward the camel. Although he had never been here before, he had traveled similar country often enough to make a reasonably accurate guess as to the terrain that lay ahead.

It was a land of low hills, or hillocks, whose sides and narrow crests supported a straggling growth of Aleppo pine intermixed with scrubby brush. There was more than average rainfall, so the trees were bigger and not as parched as those found in very arid regions. The camel was in a gulley between the second and third hills. Ali climbed the hill, slunk behind an Aleppo pine, peered around the trunk and gasped.

There was a camp in the gulley—and a string of baggage camels and men—but at first glance Ali saw nothing except the dalul. Of a deep fawn color, which stamped it as one of the Nomanieh dromedaries, it was still so young that it had not yet attained full growth. Located apart from the rest, each separate leg was held by a separate rope, and the bonds were stretched so tightly that the beast could hardly move. A fifth rope, that encircled its neck, was equally tight.

Evidently bound in such a fashion for many hours, the young dalul was weary, thirsty and choking. But, despite its obvious misery, this was far and away the most magnificent beast Ali had ever beheld. It was the riding camel he'd often dreamed of when, plodding along some lonely caravan trail, he'd conjured up mental images of the perfect dalul.

Further examination revealed why the young dalul was bound so cruelly. Ali's lip curled in contempt.

The men—he counted nineteen—were part of the same band of Druse tribesmen who'd pillaged the camp of Sofad and massacred its people. Evidently they considered themselves safe here, since they kept no watch at all and seemed to be unconcerned about anything. The twenty-nine camels on the picket line were all stolid baggage animals such as even Druse could handle. The young dalul was something else.

There was no telling just how it had fallen into the hands of the Druse; a dalul so fine would certainly be carefully guarded. Regardless of how the raiders had obtained the animal, they could not handle it. Obviously, it had turned on them and probably hurt somebody—Ali voiced a fervent hope that the injury was not a light one—and now the dalul was tightly bound, to insure that it would hurt nobody else.

Ali whispered, "Have patience, brother."

Slowly and thoroughly, beginning at one end and letting his eyes move alertly to the other, Ali inspected the camp and confirmed an ugly truth that had already been pointed out by common sense. With eight good men at his back, and the element of surprise in their favor, he would have a reasonable chance of storming the camp. But, as things were—

He'd help neither the dalul nor himself by joining his ancestors at this moment, Ali decided. He pulled the burnous over his head, drew the dagger from its sheath and settled down to wait.

The light grew, and the heat with it, as the sun climbed higher. Ali risked moving just enough to pick up a pebble and put it on his tongue. He had no water, and if the wait proved a long one, the pebble would help relieve thirst. He must not move again, though. The merest flicker could be one too many, and certainly a Druse tribesman with even a baggage camel could run down a man who hadn't any.

A camel rider, coming into camp from the south, roused not the least interest among the men already there, and Ali took mental note of the incident. Doubtless these raiders were flanking the great Hadj, but surely they could not be insane enough to attack it. Probably they intended to waylay small groups coming from various sources to join the Hadj, just as they had the camp of Sofad. The very fact that the camel rider came almost unnoticed proved that the raiders had a sentry posted to the south, and the sentry had somehow advised his companions of the rider's approach. Apparently, they anticipated no interference from any other point of the compass.

Sudden hope rose in Ali's heart. The rider might be bringing news of another caravan to be attacked, and, if so, he and his companions would depart very shortly. Since they did not know how to control it anyhow, they would not take the dalul with them. Ali's eyes strayed back to the tethered animal.

It must have come from the very choicest of the riding camels of some mighty official. Even the Pasha of Damascus would not have many such, for the simple reason that there weren't many. More than ever, it represented all the perfection dreamed of by some camel breeder—some long-dead camel breeder, since the dalul had never been produced in one generation or during the life span of one man—who knew the desert and yearned for the ideal camel.

Watching the dalul, Ali found his own mounting thirst easier to bear. The animal had been without water longer than he and probably was desperate for a drink—but refused to show it. Ali had learned while still apprenticed to the rug vendor that camels may be as thirsty as any other creatures. He turned his eyes back to the men.

One, in a rather desultory fashion, was mending a pack saddle. Two or three others were at various small chores and the rest were sleeping in the shade of their own tents. The hardness flowed back into Ali's eyes.

No followers of Mohammed, the Druse were devoted to heathen gods and rituals. It was not for that, or their hypocrisy—a Druse tribesman going among other peoples usually pretended to accept the religion of his hosts—or their thievery, or the fact that they seldom attacked anyone at all unless the odds were heavily in their favor, that Ali now hated them. He'd have hated anyone at all who mistreated such a dalul in such a fashion!

It occurred to Ali that he had neglected the prayer he should have offered immediately after the sun rose and probably would have to omit proper ceremonies at high noon, but it did not worry him. Allah, the Compassionate, would surely understand that there are certain inconveniences attached to the observance of prayers while in the full sight of hostile Druse. Nor would He frown upon Ali for refusing to let the dalul out of his sight. When Ali left the camp, the dalul was leaving with him.

Passing the noon mark and starting its swing to the west, the full glare of the sun no longer burned down on Ali's burnous, and the branches of the Aleppo pine offered some shade. But since the day became hotter as it grew longer, with the hottest hour of any being that one just preceding sunset, there was little relief from the heat.

Ali lay as still as possible, partly because the slightest motion would be sure to excite the curiosity of any Druse who happened to glance his way and partly because moving must inevitably make him hotter. Helping him to accept with grace what almost any other man of almost any other nation would have found an unendurable wait were certain talents and characteristics that had been his from birth.

Though he'd never even known his own father, Ali was of ancient blood. Few of his ancestors, throughout all the generations, had ever had the facilities, even though they might possess the best of reasons, for going anywhere in a hurry. Ali came of people who knew how to wait, and added to his inheritance was his experience with the caravans. Regardless of when a shipment had been promised for delivery in Baghdad or Aleppo, it lingered along the way, if the camels that carried it developed sore feet en route.

In some measure, Ali suffered from heat, and, to a far greater extent, he knew the tortures of thirst, but he accepted both with the inborn fatalism of one who knows he must accept what he can neither change nor prevent. Heat and thirst were passing factors. Unless he died first, in which event he'd join Allah's celestial family, sooner or later he'd be cool and he'd drink.

There'd been little action in the camp all day, but toward night the Druse stirred. They did so surlily, grudgingly, after the fashion of men who do not like what they've been doing in the recent past and have no reason to suppose they'll be doing anything more interesting in the near future. Rather than build cooking fires, they nibbled dates, meal and honey cakes, and drank from goatskin flasks. There was no singing, not even much shouting. The Druse, born raiders who could be happy only when in the saddle and riding to the attack, must now be unhappy and snarl at each other because their scouts, who were doubtless haunting every caravan trail, had brought no news of quarry sighted.

Night came, and with it a coolness so refreshing that it inspired Ali to thoughts of the heavenly bath that must be enjoyed by Allah's angels. The cool night air fell and enfolded him like a gentle flood, but with no hint of the earth's dross. After a blazing day, it was as welcome as the sight of green palms ringing an oasis.

Ali reveled in the coolness, but not nearly as much as he did in the fact that, with night, the Druse camp quieted. After waiting another hour, he drew his dagger and went forward.

The sky was cloudless, but there was no moon and, at this early hour, very few stars shone. Ali advanced with silent and unfaltering speed, in spite of the fact that he could see almost nothing. A dozen times during the day he had marked the exact route between himself and the young dalul. He knew where he was going.

Ali's fingers tightened on the dagger's hilt. If Allah saw fit to reveal him to the Druse, he hoped that the All Merciful would see equally fit to defend himself manfully. When Ali was within a dozen yards of the dalul, the peaceful night was shattered by an alarm.

"Ho! Wake and arm! There is an enemy among us!"

Because that was all he could do, Ali began to run. He had cast his lot, and now all depended on the dalul. If he could free it, then mount and ride, he and the camel would be safe at least until morning.

Ali was within an arm's length of the dalul when it turned and spoke to him. It was a guttural sound, and scarcely audible, but as different from the usual camel's grunt as the scream of a hawk is from the chirp of a robin. Even as he flung himself forward and started slashing at the nearest rope, Ali heard and correctly interpreted.

The dalul had just said that it would kill him if it could!

The picketed camels, that never saw any reason to give way to excitement just because humans did, shuffled their feet, grunted and went on munching fodder. His warning voiced, the young dalul remained silent. He would waste no more breath on threats or further warnings; just let any man who came near enough look to his own safety! His very silence had all the lethal promise of a poised, unsheathed dagger!

Ali said, "I hear, oh lord of all dalul, and I understand. But behold, I free you!"

He spoke calmly, and there was no fear to be detected by the young camel because there was none in Ali. This young camel driver, who had seen the shadow of death, or heard death whisper, as frequently as did all those who ventured forth on the lonely caravan routes, now assured himself that he was not necessarily looking upon a forbidding being in this tortured camel. But, be that as it may, he must take the chance. The incurably ill, the weary old, the oppressed, the mistreated, knew no friend more kind than Ali.

However, though he talked slowly and softly, he moved swiftly as a leaping panther while he cut the first rope and went at once to the second. The Druse camp was silent, and had been since that first shouted alarm, but it was alert and the Druse were no fools. Certainly they would know better than to come yelling and leaping, brandishing weapons and mouthing threats.

Far more probable, Ali wouldn't even know an enemy was within striking distance until he saw—or felt—the pointed dagger that was seeking his heart or heard the swish of a descending sword. Then, if Allah so decreed, one less camel driver would return to the caravan routes.

As he cut the remaining ropes, Ali continued to speak soothingly to the young dalul. Far from nervous, or even slightly excited, the young rescuer was almost serenely calm. Death would certainly be his portion if the Druse had their way, and, of course, there was also a good chance that he would die if he liberated the young dalul. But some deaths are much sweeter than others.

It would be far easier, and more honorable, to die under the trampling feet of a good Moslem dalul than under the sword or dagger of a heathen Druse. Besides, even though the dalul first killed Ali, there remained the satisfactory probability that he would then turn upon and kill one or more of the villains.

Ali cut the final rope, the one about the dalul's neck, and waited calmly. He lowered the hand holding the dagger. He'd have sheathed the weapon, except that one or more of the Druse might be upon him at any moment and a dagger would be a convenient article to have in hand. But Ali had no intention of fighting the dalul, or even of resisting should it attack him.

He said calmly, "You are free, brother."

Not accustomed to freedom after standing so long bound by cramping ropes, the dalul shook his head and stamped his forefoot. Then he gave two prodigious sidewise leaps toward the picketed baggage camels and roared.

The baggage camels crowded very close together, as though for the comfort each found in the others, when the dalul leaped. His roar robbed them of common sense, so that they began a wild plunging. Even better than Ali, the baggage camels knew the dalul's quality. They'd have broken their tethers and stampeded had not some of the Druse taken note of the situation and rushed in to quiet the terrified beasts.

For the first time, Ali had a few fleeting moments to wonder why he still lived. It had seemed inevitable that, if the Druse did not kill him, the dalul most certainly would. Perhaps, during the tortured hours it had stood as captive, it had marked its enemies and knew Ali was not among them. More probable, Ali's gift, his ability to understand and be understood by all camels, had proved itself once again.

Ali shrugged. He didn't know, and probably never would know, just why the dalul had not killed him the instant it was free. But Allah knew, and it was not for Ali to question or even wonder about His judgments.

Ali's business was camels. He decided that it was high time he took his business in hand and called the dalul.

It responded, but before coming all the way to Ali, it stopped twice to bestow a long, lingering and disappointed look upon the camp of the Druse. Raging, but bound and helpless, the dalul had promised his captors a battle as soon as he was free. The challenge still stood, and, even though the Druse were not accepting, the situation rebounded to Ali's benefit. While the dalul roamed the camp, the enemy dared not move freely, and Ali's peril was correspondingly less.

After his second inspection of the enemy camp, the dalul did not stop again or even look about him but continued straight to Ali. He halted a few steps away and grunted a little camel song. Then he extended his long neck and lightly laid his head on his rescuer's shoulder. Ali embraced the great head with both arms and pressed his cheek close to the dalul's neck.

"Mighty one!" he crooned. "Peerless one! Where is a name worthy of such as you?"

The Druse were continuing the hunt, and when and if they found Ali, they'd be overjoyed to kill him as dead as possible in the shortest necessary time. But creeping into an armed Druse camp, his only weapons a dagger and courage, was one matter. Waiting beside the young dalul, whom the Druse had every reason to fear, was quite another. Again Ali addressed the young stallion.

"Sun of cameldom! Jewel of the caravan routes! By what title may you be called so that, wherever you may venture, all men shall know your deeds when you are called by name?"

The young dalul—and if he had the faintest interest in the name Ali or anyone else might bestow, there was no indication of that—took his head from Ali's shoulder to sniff his hand. Obviously, it was high time for Ali to seek divine assistance in determining a name for the dalul, and it would not come amiss to indicate that haste was in order. Even Druse tribesmen, knowing Ali was in camp but failing to find him, must sooner or later deduce that he was with the dalul.

Ali faced Mecca. He began his supplication with the customary "Allahu akbar—God is most great." He ended it at precisely the same place, more than a little overwhelmed by the speed with which Allah may respond to even the least of His worshipers. Ali had scarcely started when he knew the name he sought. He whirled to the dalul.

"From this moment you shall be known as Ben Akbar!" he declared happily. "Ben Akbar!"

Transcending mere perfection, the name was a stroke of genius. Ben Akbar, the unequaled, the peerless, the greatest dalul of any. No matter how hard they racked their own brains, regardless of the masters of rhetoric they might consult, no camel rider anywhere would ever hit upon a name that described his favorite in terms more superlative.

Now that Ben Akbar bore the only name that truly conformed to his dignity and power, Ali turned his thoughts to affairs of the moment.

His entry into the Druse camp, audacious though it had been, never would have created other than momentary alarm. Freeing Ben Akbar, a confirmed killer camel in the mind of every Druse, gave a wholly different meaning to the entire affair. The least of the raiders would happily prowl the camp in search of Ali. But while darkness held sway, not even the best of them cared to chance an encounter with Ben Akbar.

In addition, or so the Druse would think, killer camels made no distinction among Moslems, Christians, Jews, or men of any other faith. They killed whomsoever they were able to catch. Since Ali had been near enough to cut the dalul's bindings, it followed that the killer camel had been able to catch him.

Regardless of anything the Druse thought at the moment, Ali knew that they would not continue to remain deceived after sunrise. The signs, the tracks, would be there for them to read, and few desert dwellers read signs more skillfully. Despite anything their minds told them, their eyes would leave no doubt that Ali and the dalul had gone away together.

For a brief interval, Ali speculated concerning the inscrutable ways of Allah, who had bestowed upon the Druse tribesmen a maximum of ferocity and a minimum of common sense. Obviously, it was his duty to take certain most urgent action if he would live to greet another sunset.

At night, the Druse would have no stomach for attacking, or even coming near, Ben Akbar. As soon as a new day brought light enough so they could see, they'd never hesitate. If Ali happened to be near Ben Akbar, where he had every intention of being, he'd be found.

Ali said softly, "We go, brother." With Ben Akbar pacing contentedly at his shoulder, he faded into the darkness.

Although Ali wanted to go south, where he thought he'd have the best chance of meeting the great Hadj, and the gulley in which the Druse were camped ran almost directly north-south, he did not go down that gulley. There was at least one enemy outpost stationed there—and possibly more.

Ali climbed the ridge, retracing almost exactly the path he'd followed when he came to the rescue of Ben Akbar. Rather than stop when he gained the summit, he went on down into the next gulley and climbed the following ridge. On the summit of that, he finally halted. Ben Akbar, who sported neither tether rope nor rein but who was amiably willing to walk behind Ali where the path was narrow and beside him where space permitted, came up from behind and thrust his long neck over his friend's shoulder. Ali reached up to caress the mighty head.

The baggage animals he'd seen in the Druse camp were just that, ponderous beasts, bred to carry six hundred or more pounds a distance of twenty-five miles at a stretch and to bear this enormous burden day after day. Under ordinary circumstances, they'd be no match for the dalul, but Ben Akbar was more than just tired and hungry. An hour of the torment he'd endured was enough to sap more strength than an entire day on the trail. His hump, that unfailing barometer of a camel's condition, was half the size it should have been. There was no way of telling when he'd had his last drink of water.

This last, Ali told himself, was of the utmost importance. Every urchin on every caravan route knows that camels store water in their own bodies, and that it is entirely possible for some seasoned veterans of the caravan trails to plod on, though at an increasingly slower pace, for three, four, or even five days without any water save that which they absorb from their fodder. But those are the exceptions. As noted, given an opportunity, camels will drink as much and as frequently as any creature of similar size, and a thirsty camel is handicapped.

So, although Ali might have laughed in their faces had Ben Akbar been rested and well-nourished, the Druse, who would most certainly be on their trail the instant it was light enough to see, had more than a good chance of overtaking them before nightfall. But before Ali could concern himself with the Druse, there was something he must do.

"Kneel!" he commanded.

Ben Akbar knelt, settling himself with surprising grace. Ali mounted. Though there was no riding saddle, he seated himself where it should have been and placed his feet properly, one on either side of the base of Ben Akbar's neck. There was no rein either, but the finest of the dalul were carefully schooled to obey the spoken word without regard to rein. Ali gave the command to rise, then bade Ben Akbar go.

Ben Akbar's gait was as gentle as the evening wind that ruffles the new-sprouted fronds of young date palms. Ali sent him to the right, then the left, relying on spoken commands alone and getting a response so perfect that there'd have been no need of a rein, even if the dalul wore one. Ali no longer had reason to wonder if Ben Akbar was the property of a rich man. None except the wealthy could afford the fees demanded by riding masters who knew the secret of teaching a camel to obey spoken orders.

Though he knew he should not, Ali ordered Ben Akbar to run. The camel obeyed instantly, yet so imperceptible was the change in pace, and so rhythmically smooth was his run, that he had attained almost full speed before his rider realized that the change had been made.

Ali sat unmoving, letting the wind fan his cheeks and reveling in this ride as he had delighted in nothing else he could remember. The gait of riding camels varies as much as that of riding horses, but Ben Akbar stood alone. Rather than landing with spine-jarring thuds as he raced on, his feet seemed not even to touch the earth.

Ali had never ridden a smoother-gaited camel...but suddenly it occurred to him that the ride had better end. Bidding his mount halt, Ali slid to the ground and went around to where he could pet Ben Akbar's nose.

"You are swift as the wind itself, and the back of the downiest bird is a bed of stones and thorns compared with the back of Ben Akbar," he stated. "But it is not now that you should run."

Ben Akbar sniffed Ali gravely and blew through his nostrils. Ali responded, as though he were answering a question.

"The Druse," he explained, "tonight they are helpless, for even if they would follow, they cannot see our path in the darkness. But rest assured that they shall be upon our trail with the first light of morning and they know well how to get the most speed from their baggage beasts. If you were rested and nourished, I would laugh at a dozen—nay!—a thousand such! But you are weary and ill-cared-for, so tonight we must spare your strength. Tomorrow, you may have to run away from the Druse!"

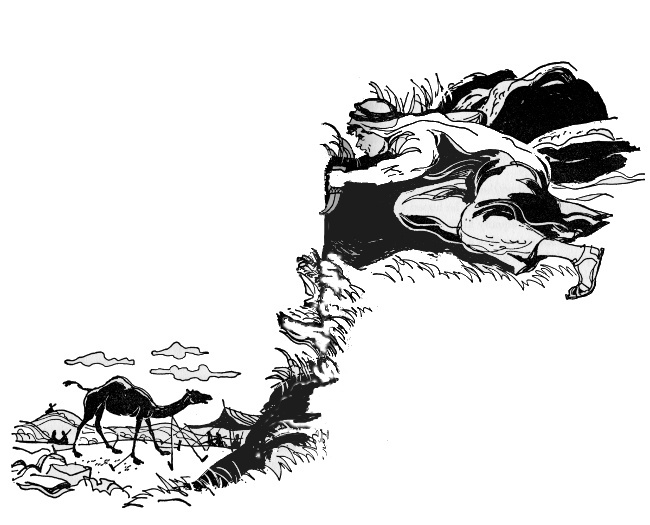

The next day was two hours old, and Ali and Ben Akbar were still walking south, when Ali glanced about and saw the mounted Druse sweep over a hillock.

At the same instant, they saw him and raced full speed to the kill.

Hearing, scenting or sensing pursuit, Ben Akbar swung all the way around. He was very quiet, an indication that he would look to and obey Ali. But there was about him a complete lack of nervousness, plus a certain quality in the way he faced enemies, rather than turned from them, that betrayed a war camel. He would flee from the Druse, if that were Ali's wish, but he would run just as eagerly and just as swiftly toward them, should Ali decide to attack.

Nervous, but controlling himself, Ali counted the Druse as they raced down the hill. There were twenty-three, three more than had been in camp last night, therefore some must have arrived after he left. They were not the organized unit they would have been if they expected formidable resistance. Since there was only one man to kill, and every Druse burned to kill him, they came in wild disorder, with those on the swiftest camels leading.

Though the charge was only seconds old, three of the Druse had already drawn ahead of the rest. A glance told Ali that all three were mounted on dalul. Since there had been no riding camels in the Druse camp, obviously these were the three newcomers who had arrived during the night. The rest were all mounted on baggage camels.

Because he had had a whole night's start, and the pursuing Druse should have been hampered by the necessity for working out his trail, Ali had not expected them before midday. Something had gone amiss. Possibly, during the night, Ali and Ben Akbar had passed another outpost that they had not seen, but that had managed both to shadow them and to send word back to the camp. Perhaps the outpost had even consisted of the three riders of dalul.

Ali concentrated on the three dalul. All were good beasts, but none were outstanding, and, in an even contest, none could have come near to matching Ben Akbar's speed. No, however—

Ali turned to Ben Akbar and said gently, "Kneel."

Ben Akbar obeyed. Ali mounted and gave the command to rise, then to run. He unsheathed the dagger and held it in his hand. The Druse were armed with guns, which they knew how to use, but there were good reasons why they would hesitate to shoot one lone man. In the first place, powder and shot were expensive and to be used only when nothing else sufficed. In the second, when the odds were twenty-three to one, the Druse who shot when he might have killed his enemy with sword or dagger must lose face as a warrior.

The dagger in his hand was Ali's only concession to the possibility that he might be overtaken. When and if he was, might Allah frown if at least one of the Druse did not join his ancestors before Ali did likewise.

Other than that, the race was not unpleasant. Weary though he was, the power and strength that Ali had seen in Ben Akbar when the young dalul stood captive in the Druse camp were manifest now. Ben Akbar flowed along, seeming to do so almost without effort, and Ali thought with wonder of the magnificent creature this dalul would be when properly fed and rested. Only when Ben Akbar stumbled where he should have run on was his rider recalled to the grim realities of the situation.

He did not have to look behind him because he knew what lay there. Having been detected when they appeared over the crest of the far hillock, the Druse must still descend it, cross the gulley and climb the opposite hill before they could be where Ali had been when they saw him. Though they must know that Ben Akbar was not in condition to run his best, they certainly knew the quality of such a camel. Looking from the crest of the hill upon which Ali had been sighted and seeing nothing, they could by no means be certain that camel and rider had not already gone out of sight on the hill beyond. A terrified fugitive would logically run in a straight line.

A third of the way down the hill, Ali gave Ben Akbar the command to turn left. He was about three hundred yards from the floor of the gulley and the same distance from its head, where a thick copse of mingled Aleppo pine and scrub brush offered more than enough cover to hide a whole caravan. Reaching the thicket, Ali halted Ben Akbar and dismounted. Then he turned and waited for the Druse to appear.

Led by the three riders of dalul, they broke over the crest at the exact spot where Ali had been sighted. They did exactly as he had hoped they would and raced straight on. A smile of satisfaction flitted across Ali's lips as the advance riders swept past that place where he had turned Ben Akbar.

Then something went amiss.

Though the three dalul had seemed equally matched, one now led the other two by some ten yards. Reaching the gulley's floor, the leading rider halted his mount, swung him abruptly and shouted, "He has gone another way!"

As the truth forced itself on Ali, his first thought was that the rider of the leading dalul must be a very giant among the Druse.

Noted trackers, most Druse would have some trouble trailing a single camel on a sun-baked desert. But, incredible though it seemed, the leading pursuer had been tracking Ali while riding at full speed. He had raced on because he had thought exactly what Ali hoped he would—that Ali and Ben Akbar were already out of sight behind the next hill. But he had stopped when he no longer saw tracks.

While the two remaining riders of dalul swung unquestioningly in behind him, and the Druse mounted on baggage camels halted wherever they happened to be, the tracker trotted his dalul back up the hill. His eyes were fixed on the ground as he sought to pick up the trail he had lost.

With Ben Akbar behind him, Ali stole through the thicket toward the far end. He clutched the dagger tightly. He would mount and ride when he was clear of the thicket; nobody could ride a camel through such a place. But it was questionable as to how long he'd ride with such a tracker on his trail.

Ali was almost out of the thicket when a man who swung a wicked-looking scimitar seemed to rise from the earth and bar his path. Ali gazed upon the countenance of an old acquaintance.

The man was a Druse that Ali knew as The Jackal!

Ali took a single backward step that brought him nearer Ben Akbar. The move could have been interpreted as a wholly natural desire to find such comfort as he might in his camel, the one friend he had or was likely to have. But Ali's purpose was more practical.

Unless every imaginable advantage was on his side, the wielder of a dagger hadn't the faintest chance of overcoming anyone armed with a scimitar, but Ali intended to concede no point not already and unavoidably given by the difference in weapons. When The Jackal swung, which he would do when he considered the moment right, he would not miss. But if Ali was agile enough at ducking, and ducked in the right direction, it did not necessarily follow that he must be killed outright.

For a split second immediately following his blow, The Jackal would be off guard. Before he recovered, always supposing he was still able to move, Ali might go forward with his dagger and work some execution, or at least inflict some damage, of his own. All else failing, there was reason to hope that Ben Akbar would trample his foe after he went down. Ali studied The Jackal.

Of medium height and probably middle-aged, he was veiled in a certain mystic aura that defied penetration and prevented even a reasonably accurate guess as to how many years he had been on earth. He blended in a curious manner with the harsh and wild desert background, as though he had been a part of it from the beginning. His hair was concealed beneath a hood, but not even a thick beard succeeded in hiding a cruel mouth. His nose was thin and aquiline, with nostrils that seemed forever to be questing. His eyes were unreadable, but they possessed certain depths that combined with a broad sweep of forehead and a vast arrogance of manner to mark The Jackal as a man apart.

Ali remembered the first time he had run across him, or rather, evidence of his work.

It was Ali's third year with the caravans, and they were going from Mersin to Erzerum, with seven hundred camels and an assorted load, when they overtook all that remained of the caravan preceding them. It had been the entourage of some wealthy Amir, traveling north with his family and a powerful guard of soldiers. When Ali arrived, The Jackal had been there and gone, but he had left his trademark.

All human males, from babes in the arms of his wives to the gray-bearded Amir himself, lay where they had fallen. The older women and the girl children were massacred, too. Only the young girls had been carried away with the remainder of the legitimate booty.

Savagely cruel though it was, the raid was equally audacious. Of the many bandit leaders infesting the caravan routes, few had the imagination to plan a successful attack on a heavily-guarded Amir's caravan or the courage to proceed, once such an attack was planned.

Thereafter, at sporadic intervals, Ali found additional evidence that The Jackal was still at work, and there could be no mistake about his identity. His raids were noted for cruelty and for the fact that he never bothered with any except wealthy caravans. Three years later, Ali met The Jackal.

The caravan for which Ali was handling camels came to an oasis one day out of Ankara and found another caravan already encamped. However, there was ample room for both and no apparent reason for either to challenge the other. Ali took care of the camels for which he was responsible, then set about to do something he would have done before had an opportunity offered itself.

He had been in Antioch, temporarily idle, when he happened across a youngster mishandling some half-broken baggage camels. He had stepped in to bring the situation under control. On succeeding, he discovered that the young man had disappeared while he was occupied, and an older person was quietly watching him instead. The older man, whom Ali thought was the caravan master, invited him to come along as a camel driver.

Ali had accepted and discovered, too late, that the imperious youngster who'd been mishandling baggage camels was the real caravan master, which position he held solely by virtue of the fact that his father was Pasha of Damascus. He didn't like Ali and he missed no opportunity to demonstrate his disapproval. Ali had stayed with the caravan until reaching this oasis for the simple reason that there was no other choice. If he had left sooner, he would have been one lone man in a land noted for the brief span of life enjoyed by solitary travelers. But he felt that he could make it from here to Ankara without difficulty and he'd had more than his fill of the Pasha's son. He went to the caravan master's tent to demand his pay.

He found the youngster engaged in amiable conversation with the man who now stood before him, The Jackal, who said he was master of the other caravan. Ali also found that, in the eyes of the Pasha's son, his own state was less than exalted. He was ordered out of the tent.

When Ali refused to leave without first receiving his pay, the youngster unsheathed a dagger and advanced with the obvious intention of having him carried out feet first. Unluckily for the Pasha's son, Ali also had a dagger and his skill with the same exceeded by a comfortable margin any adroitness the other might claim. Ali got his due wages, which he took from a moneybag, and the Pasha's son had fainted from a series of dagger wounds in his right arm.

Ali was on the point of leaving when The Jackal, who had offered not the faintest interference, rose, complimented him on a superb bit of dagger work and thanked him for making it easier to sack the caravan. He intended to do this tomorrow, somewhere between the oasis and Ankara, but the Pasha's son had presented an awkward problem. The Jackal, who introduced himself as such, had no fear of soldiers in reasonable numbers but he was not prepared to cope with the armies that must inevitably take the field against whoever molested a son of the Pasha—this despite the fact that the Pasha had no fewer than twenty-nine known sons. The Jackal had been trying to persuade the young man to leave and go into Ankara when Ali's dagger had settled the matter in a most satisfactory fashion.

The Jackal was not ungrateful, and, to prove his gratitude, he would arrange for Ali to ride into Ankara with a small group of his own men, who would leave shortly. After they had gone, The Jackal would see to it that a sufficient number of his own trusty brigands, under such oaths as might be appropriate, would swear that they had seen the Pasha's son struck down by an unknown assailant.

Ali had ridden and so had escaped the next morning's massacre, which several travelers had reported as taking place after the Pasha's son had been "killed by an assassin." Thereafter, he had waited for lightning to strike although he had only injured his attacker in self defense, but so far, it hadn't which meant that The Jackal had kept his lips sealed. Now it no longer mattered. The Jackal would cut his own mother down if by so doing he served his own ends.

Suddenly, "Why hesitate, Abdullah?" somebody growled.

Another man came from the brush to stand beside The Jackal. Then there was another...and more...until nineteen men were grouped about The Jackal and facing Ali. The Jackal stepped aside. Another took his place.

Ali glanced briefly at The Jackal. He looked at the others, all good Moslems and all wearing on their turbans the distinctive emblem that marked them as members of the Pasha's crack personal soldiery. The present "Abdullah," the former Jackal, wore the same emblem but, until now, it had escaped Ali's notice because, not in his wildest flight of imagination had he dreamed he'd ever see it on a Druse.

The soldier who'd spoken and for whom The Jackal had stepped aside, evidently the commander of this patrol, spoke again and directed his words to Ali, "Where found you the dalul, dog?"

Ali answered, "I stole him from some Druse."

The soldier drew his dagger and spoke again, "Die you will, but choose whether you die swiftly or slowly. Why are you found in possession of the finest dalul among two thousand such owned by the Pasha of Damascus?"

"I stole him—" Ali began.

At that moment, out in the thicket, one of the camels being led by the dismounted Druse as they made their way among the trees and brush, chose to grunt. The eyes of every man except the officer turned toward the sound.

Ali said, "The Druse from whom I stole the dalul are in close pursuit. They are twenty-three in all."

Except for the officer, who thoughtfully kept the point of his dagger pricking Ali's ribs, the Moslems scattered and, a few seconds later, it was as though they had never been.

The officer addressed Ali. "Bid the dalul lie down."

Ali gave the order and Ben Akbar obeyed. Unconcerned as though there were no Druse within forty miles, but not forgetting to prick Ali's ribs with his dagger, the officer scorned even to glance in the direction from which the Druse approached. Ali wondered. Some Moslems yearned so ardently for the life to come that they set not the least value on the one they already had, but the officer seemed more practical-minded.

"The Druse number a score and three," Ali ventured finally. "They come from the direction where the camel grunted and they cannot fail to see you should you neglect to hide."

"I did not ask your opinion," the officer growled. "Be silent!"

Since the order was emphasized with a sudden jab of the dagger, Ali remained silent. He composed himself. This, as well as everything else, was now in the hands of Allah and He alone would determine the outcome. But it never harmed anything to ponder.

The rest of the Moslems and The Jackal had disappeared as suddenly and completely as morning dew when the sun turns hot. Though they could not be very far away, neither was the end of the thicket. Once out of the brush, Ali could mount Ben Akbar and ride. If the pursuit were resumed, and, regardless of who won the forthcoming battle, it would be, it must still be delayed while the fight was in progress. If Allah would only see fit to make the officer take the point of his dagger out of Ali's ribs and go wherever his men had gone, it would be worth Ali's while to try to break away.

But the officer entertained no ideas about going anywhere or of using his dagger for any purpose except to remind Ali how swiftly a painful situation could become fatal. Ali looked at Ben Akbar, still lying where he had been ordered to lie, but not liking it. Though reclining, he was anything but relaxed. His head was up, his eyes missed nothing, his nostrils quested, and tense muscles indicated both a readiness and an ability to spring instantly to his feet.

Ali decided that Ben Akbar did not like these strange Moslems any better than he had the Druse who captured him, and that he tolerated them at all only because Ali commanded him to do so. It occurred to Ali that none of the Moslems had been eager to venture too near Ben Akbar, and, suddenly, he knew something he hadn't known before.

Certainly no killer, Ben Akbar was most discriminating when it came to a choice of human companions. Incapable as the Druse of handling him properly, the Moslems were wisely leaving him alone. The fierce little officer never would have told Ali to make Ben Akbar lie down if he thought the dalul would obey him instead.

That being so, and if Allah smiled and the Moslems won the forthcoming fight, Ali felt that he had some hope of staying alive, at least until the soldiers returned to whatever headquarters camp they had left to go out on patrol. It would reflect little credit on any emissary of the Pasha of Damascus to bring a favorite dalul before the eyes of his master as a raging brute at the end of ropes. If the Moslems could not take him in except by force, but Ali could, there were reasons to suppose that Ali would.

When they appeared on foot, the Druse were led by a sinewy man who advanced at a trot, and who, in turn, led a dalul. Evidently the same talented tracker who'd followed Ali's trail while riding full speed, the man strained like a leashed gazelle hound that sights its quarry. The remaining Druse grouped behind him.

Ali glanced at the officer.

That fierce Moslem, who certainly knew the Druse were coming, contemptuously refused even to look around until the leader was within thirty yards of him. Then, maintaining enough pressure on the dagger to remind Ali that he was not forgotten, he swung and shouted insults.

"Dogs!" he spat. "Eaters of pork! Spawn of flies that infest camel dung! I have your prisoner and your dalul! Come take them if you're men!"

The leading Druse dropped the reins of his dalul, shouted fiercely, drew his sword and rushed. His followers did likewise, and, even though some were delayed by frightened camels that plunged to one side or the other, Ali counted nine sword-waving Druse hard on the heels of their leader and all too close for comfort. He stole another glance at the officer.

Neither taking the dagger from Ali's ribs nor making any move to draw his sword, he seemed to regard the attacking Druse as he might some particularly repulsive vermin that might soil his shoes if he stepped on them. Then it happened.

From both sides of the trail, where they had concealed themselves as soon as they knew the Druse were coming, Moslem swordsmen rose. So complete was the surprise and so overwhelming the shock, half the Druse were down before the rest even thought of rallying. Ali acknowledged his approval—and even some admiration—for an officer who could plan so well.

The ambushed Moslems must have seen Ali and Ben Akbar when they were at least as far off as the Druse had been when they were sighted. They had marked the exact route, which made it unnecessary to do any second-guessing about the Druse. If they were following Ali, they were tracking him. So an ambush on either side of the track, an officer to act as bait and convince the Druse that there was only one man and—

The last Druse went down. The Moslems ranged out to catch the scattered camels and bring in any loot that was worth bringing. Some wounded, but all on their feet, they arranged themselves and their booty before the officer.

"You fought like old women," he sneered. "It is well that there were no real warriors to oppose you. But now that we have the dalul we set out to find, we may return."

"The prisoner?" someone called.

"He stays." The officer pushed his dagger a quarter inch into Ali's ribs.

Because it was an ideal time to think of something else, Ali speculated about The Jackal. Whatever else he might be, The Jackal was a brave man. What would happen, if he were detected, to a Druse who not only joined the Hadj but the Pasha's personal soldiers too, and who was obviously representing himself as a Moslem, Ali couldn't even imagine.

He did know that one false step would be one too many for the deceiver. If The Jackal took that step, he would live a very long while in agony before voicing his final shriek. Of course, it was a true Moslem's duty to tell what he knew, but The Jackal had only to speak and Ali would face the torturers with him. Whatever purpose had brought The Jackal here, he must be playing for tremendous stakes.

Ali was considerably relieved, but not greatly astonished, when the officer withdrew his dagger and sheathed it. He addressed Ali as he might have spoken to a stray cur.

"On second thought, we will take you to Al Misri, The Egyptian, and let him kill you. Bring the dalul, dog, and, for your own sake, see that it does not stray."

As soon as possible, which was as soon as their own riding camels could be brought from wherever they had been hidden, the Moslem soldiers mounted and prepared to set out. On the point of mounting Ben Akbar, Ali was knocked to the ground by the flat of the fierce officer's sword and informed in terms that left no room for doubt that he was Ben Akbar's attendant. Nobody except the Pasha of Damascus was to be his rider.

Despite clear grounds for argument, Ali smothered his anger and comforted himself with logic. There are times to fight, but on this specific occasion logic indicated clearly that one man armed with a dagger can hope for nothing except a very certain demise by defying twenty men who are armed with everything. Ali walked beside the dalul, a rather simple process, since the speed of all must necessarily be regulated by the pace of the slow baggage camels, and Ben Akbar refused to leave his friend's side, anyhow.

With nightfall, they made camp at a water hole too small to be dignified by the title of oasis. After he had finished eating, the officer contemptuously tossed Ali the remains of his meal and a silken cord. He said nothing, apparently he had no desire to degrade himself by speaking unnecessarily to anyone who was so clearly and so greatly his inferior, but the implication was obvious. Ben Akbar must not stray.

Knowing the cord was unnecessary, Ali chose the diplomatic course. He tied one end of the cord to his wrist and the other around the young dalul's neck. While Ben Akbar grazed, Ali sat quietly and devoted a few fleeting thoughts to the various possibilities of a social position that is approximately on a level with the fleas that torment camels—and sometimes riders of camels.

While it was true that the soldiers, grouped about their evening fire, ignored him as completely as though he didn't even exist, Ali saw no good reason why he should ignore them in a similar fashion. He breathed a silent thanks to Allah for blessing him with sharp ears. What those ears heard as Ali sat pretending to doze, but alert as a desert fox, might have a powerful influence on his plans for the future.

There were diverse possibilities. One that had already been considered most thoroughly and at great length was rooted in the pleasing thought that Ben Akbar was no longer a tired, hungry and thirsty dalul. Given as much as a five-second start, there wasn't another camel on the desert that could even hope to catch him.

If this was to be Ali's choice, tonight was the time for action. But before committing himself to anything, he wanted to consider everything.

The patrol, as Ali had learned from the conversation at the campfire, was one of several dispatched from the great Hadj six days ago. Their only purpose was to find Ben Akbar; their orders were not to return without him.

Ben Akbar had been lost, so Ali learned, through the laxity of a seven-times-cursed camel driver from Smyrna. His only duty, a task to which he'd been assigned because he was one of the very few men Ben Akbar would obey, was to watch over the Pasha's most-prized dalul. Somehow or other—a soldier voiced the opinion that he'd been in collusion with the very Druse from whom Ali had taken him—he'd managed to lose his charge. All the soldiers gave fervent thanks to Allah because their mission was successfully completed. Hunting lost camels was not their idea of interesting diversion.

Ali digested the food for thought thus provided and decided, to his own satisfaction, that his previous deduction had been entirely correct. He had not been spared because the Moslem soldiers were compassionate, but because not one among them knew how to handle Ben Akbar without resorting to force. Furthermore, if Ben Akbar were not greatly esteemed, several patrols of soldiers who might at any time be needed for other duties never would have been charged with the exclusive task of recovering him.

While Ben Akbar moved so carefully that the silken cord was never even taut, Ali lay back to gaze at the sky and consider the most profitable use of the information at his disposal.

If he rode into the desert on Ben Akbar, a possibility that retained much appeal, he need have no fear of successful pursuit. However, the Pasha's soldiers would certainly continue their search. As long as Ben Akbar was with him—and Ali had already decided that that would be as long as he lived—he must inevitably be a marked man. Unless he rode into a country ruled by some sultan or Pasha who was hostile to the Pasha of Damascus—in which event there was a fine chance of having his throat cut by someone who wanted to steal Ben Akbar—he would lead a harassed and harried life.

On the other hand, if he stayed with the soldiers and went into camp, he'd be doing exactly what he'd set out to do in the first place—he'd join the great Hadj. As there seemed to be few camel drivers who knew how to handle Ben Akbar, there was more than a good chance that Ali would make the pilgrimage as his attendant. Since he'd already determined that Ben Akbar would be a part of his future, regardless of what that was or where it led him, this prospect was entrancing. In addition, once his holy pilgrimage was properly completed, he would be entitled to call himself Hadji Ali and to take advantage of the expanded horizon derived therefrom.

Only one small cloud of doubt prevented Ali from choosing this latter course without further hesitation or thought. The Moslem officer's voice had been laden with more than casual respect when he referred to Al Misri, or The Egyptian. The casual pronouncement that The Egyptian was to have the pleasure of executing Ali might be, and probably was, just another attempt to intimidate him. But this was the Syrian Hadj. As such, it differed distinctly from the Moslem pilgrimage that originated in and departed from Cairo, Egypt. Every Syrian knew that Egyptians are inferior. The very fact that a responsible and high-ranking officer of the Syrian Hadj possessed the sheer brazen effrontery to call himself The Egyptian, plus the strength and authority to command respect for such a title, was more than enough to mark him as a man apart. Doubtless he was a man of firm convictions that were translated into action without loss of time. If he had, or if he should develop, a firm conviction that Ali dead was more pleasing than Ali alive—

Ali finally decided to go in with the soldiers and trust Allah. His decision made, he lay down, arranged his burnous to suit him and went peacefully to sleep.

In the thin, cold light of very early morning, he came awake and, as usual, lay quietly before moving. The silken cord that was tied to his wrist and Ben Akbar's neck was both slack and motionless; the dalul must be resting. The dagger and pilgrim's robe were safe. Reassured concerning the state of his personal world and possessions of the moment, Ali sat up and looked toward Ben Akbar.

No more than a dozen feet away, the young dalul was standing quietly where he had finished grazing. An ecstatic glow lighted Ali's eyes. Ben Akbar's recuperative powers must be as marvelous as his speed and endurance. He scarcely seemed to be the same spent and reeling beast that Ali had led into ambush yesterday morning. After only one night's rest and grazing, even his hump was noticeably bigger.

Ali joined the other Moslems at morning prayer, stood humbly aside as they saddled and mounted and started the baggage camels moving and fell in behind with Ben Akbar. Nobody paid the least attention to him; if he planned to escape, he would not be fool enough to make the attempt by day.

Four hours later, the travelers looked from a hillock upon the great Hadj.

A sea of tents, like rippling waves, overflowed and seemed about to overwhelm a broad valley. There were no palms or any other indication of water. Obviously, this was a dry camp—one of many on the long, dangerous route—and dry camps were the primary reason why so many baggage camels were needed. But even with thousands of baggage camels burdened with food and water, often there was not enough. Falling in that order to thirst, bandits, disease or hunger—or succumbing to the desert itself—a full third of the pilgrims with any Hadj might die before reaching the Holy City.

Save for a few tethered camels and some horses, there were no animals in sight. Ali knew that the majority had been given over to herders and were in various pastures. The picketed camels and horses were for the convenience of those who might find it necessary to ride.

For the most part, the camp would rest all day. Only when late afternoon shadows tempered the glaring sun would it come awake. Then, guided by blazing torches on either flank, at the mile-or mile-and-a-half-an-hour which was the swiftest pace so many baggage animals could maintain, it would march toward Mecca all night long.

Impressive as the camp appeared, Ali knew also that it was just a small part—though one of the wealthier parts or there would not have been so many tents—of the great Hadj. There was not a single valley in the entire desert spacious enough to accommodate the five thousand humans, and the more than twenty thousand beasts, whose destination was the Holy City of Mecca.

After a brief halt, the officer led his men down into the camp. There were few humans stirring, and those who were regarded the returning patrol with complete indifference.

In the very center of the camp, before a huge and luxurious tent that, together with its furnishings, must require a whole herd of baggage camels just to transport it, the officer dismounted, handed the reins of his riding camel to a soldier and entered the tent. The remainder of the patrol formed an armed circle around Ali and Ben Akbar.

Wishing he could feel as unconcerned as he hoped he appeared, Ali sought to ease the tension by observing and speculating. This tent, he presently decided, was not headquarters for the Pasha himself. Though the Pasha's tent couldn't possibly be much more luxurious, it would be surrounded by the camps of other dignitaries, and the whole would be so well-guarded by soldiers that nobody could have come even near. Ali guessed that this was the headquarters of Al Misri, and that they were in a camp of officers and lesser notables.

Twenty minutes after he entered the tent—Ali guessed shrewdly that he had been allowed to cool his heels for a decorous interval—the officer backed out. He bowed, a curious and somehow a ludicrous gesture for anyone so fiery, and held the tent flaps open. When a second man emerged, the officer stepped humbly to one side and waited whatever action the other might consider.

Short and squat, at first glance Al Misri seemed a shapeless lump of human flesh that has somehow been given the breath of life. His silken robe hung loosely open. Uncovered, his massive head seemed to be supported directly on his shoulders, without benefit of or need for a neck. It was bald as an egg. He plopped a date into his mouth and chewed it as the soldiers moved respectfully back to give him room.

Yet Ali needed only one glance to tell him that Al Misri was far more than just a funny little fat man who chewed dates in a rather disgusting manner. His grotesque body was enveloped in an aura not unlike that which enfolded Ben Akbar. Al Misri commanded because it was his destiny to command.

He came near, spat the date pit into Ali's face and spoke to the officer. The latter conveyed the message to Ali.

"Even though Al Misri prefers to kill vermin, you are granted your life. You win this favor, not through compassion, but because you are able to ride a dalul that kills other men."

Ali remained silent, as was expected of him. Al Misri gave the officer another message for the captive camel driver.

"The other keeper of the dalul let it stray," the officer announced. "The keeper died in a fire, a very slow fire that was kindled at dawn, but the keeper still nodded his head at high noon. You are now keeper of the dalul. Take care that it strays not."

Without another word or a backward glance, Al Misri turned and waddled back to his tent. The officer disbanded his men.

Ali led Ben Akbar to pasture at the edge of camp.

The travelers came to Tanim, far enough outside Holy Territory so that there was no possibility of desecrating it, but near enough to furnish a convenient stopping place for donning the ihram, in the cool of early morning. Not all who had been with the Hadj when Ali finally joined it—and not all who had since come from one place or another—were still present. Many good Moslems who would never see the Holy City had died trying to reach it.

Ali reflected curiously that some of the more devout were dead, while some who seemed to regard this holy journey in anything except a pious light were very much alive. A merchant who had come all the way from Damascus, and who was about to don the ihram, deferred the ceremony so that he might bargain about something or other with another merchant from Smyrna. Though they were all Moslems—except for The Jackal, Ali thought quickly—obviously the true light burned brightly for some and dimly for others.

Ali wondered uneasily about the category in which he belonged. He worried about the fact that he did not feel greatly different from the way he had felt while out on the caravan routes or in the bazaar of The Street Called Straight. He thought he should feel something else.

Though many had died, his pilgrimage had been almost luxurious. He had nothing at all to do except watch over Ben Akbar, which was simplicity itself because the powerful young dalul wanted nothing except to be where Ali was. Though Ali was forbidden to ride, the Pasha of Damascus, the only human worthy of riding Ben Akbar, had allowed himself to be carried all the way to Mecca in a sedan chair. Seeing the Pasha once, and from a distance, Ali decided, to his own satisfaction, at least, that he had not asked to ride Ben Akbar for the simple reason that he couldn't. Judging by the Pasha's looks, he'd have trouble riding an age-broken baggage camel.

Always together, Ali and Ben Akbar had walked all the way. It had still been the easiest of walks since, as long as he took care of Ben Akbar and kept himself in the background, Ali was assured ample food and water. With the finest of care and nothing to do, Ben Akbar was at the very peak of perfection.

With appropriate ceremony, Ali donned the ihram and ran a mental tally of the things he must not do until the Hadj came to an end. He must wear neither head nor foot covering. He must not shave, trim his nails—But there was nothing in the entire list that forbade taking Ben Akbar with him. Ali remained troubled, nevertheless because, try as he would, he was unable to achieve what he considered a necessary level of piety.

Rather than feeling spiritually uplifted by what had been and what was to be, he could think only that, very shortly, he would have the right to call himself Hadji Ali.

Mecca, Holy City of the Moslems, spoke in a strangely subdued whisper when this particular night finally enfolded it. The great Hadj was ended—the official termination announced when the wealthier pilgrims sought barbers to shave them and those without money shaved each other.

The unofficial, but more realistic, termination came about in a different manner.

Whatever their motives, or degree of zeal, an inspired army had gone to Mecca. With the Hadj ended, suddenly weary human beings thought with wistful longing of the homes they'd left and the beloved faces that became doubly precious because they were absent. Thus the sudden silence in Mecca, where—every night until this one—lone pilgrims and bands of pilgrims had gone noisily about various errands. However, not all pilgrims had chosen to spend this night in their beds.

Ali, now Hadji Ali, stood very quietly in the darkest niche he'd been able to find of The Masa, The Sacred Course between Mounts Safa and Marwa. Ben Akbar, never far from Ali's side, stood just as quietly beside him and Ali wanted no other companion. Hoping to ease a troubled conscience, he had sought this lonely and deserted spot to try to find the true significance, which he was sure must exist but had so far escaped him, of the ceremonies in which he had just participated.

Perhaps, he thought seriously, he was now confused because he had had no real understanding of any part of anything from the very beginning. Nobody had told him why the ihram must be donned and adjusted in a certain way, with certain prescribed motions, and in no other fashion.

With Ben Akbar, who followed like a faithful dog but aroused little comment in this city where camels were the commonest means of transportation, Ali had entered Mecca in the prescribed fashion, though he hadn't the faintest idea as to who had prescribed it or why. At intervals, and solely because all his companions were doing likewise, he had shouted "Labbaika," a word whose meaning he had not known and still did not know.

At this point, Ali became so hopelessly entangled in matters he did not understand that it was necessary to start all over again. However, he decided not to begin with the ihram this time. The Sacred Course was also a part of the ceremony, and, being near at hand, it might yield clues that could not be discerned in that which was far away.