BURTON OF THE FLYING CORPS

BURTON OF THE

FLYING CORPS

BY

HERBERT STRANG

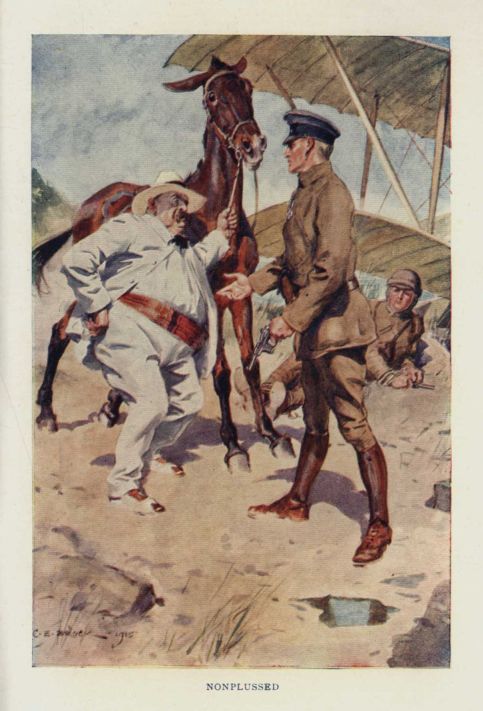

ILLUSTRATED BY C. E. BROCK

LONDON

HENRY FROWDE

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

First printed in 1916.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY R. CLAY AND SONS, LTD.,

BRUNSWICK STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E., AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

CONTENTS

Showing how Burton made a trip to Ostend in pursuit of a spy

Relating Burton's adventure in a French chateau

III BORROWED PLUMES

Showing how Burton caught a German in Bulgaria

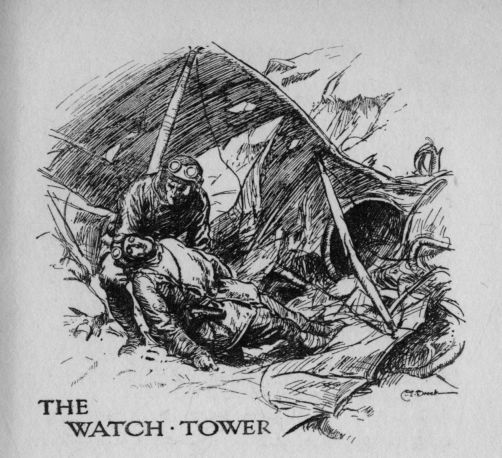

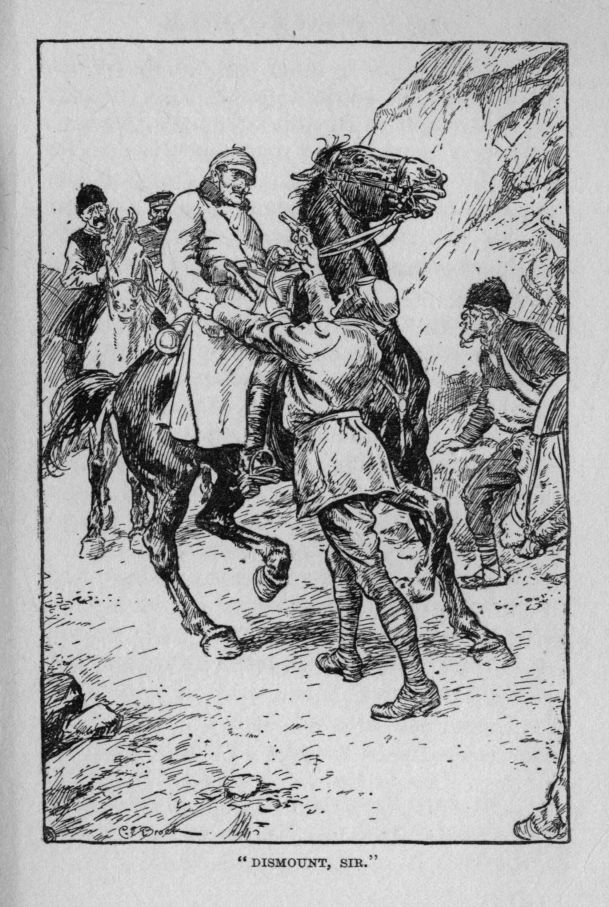

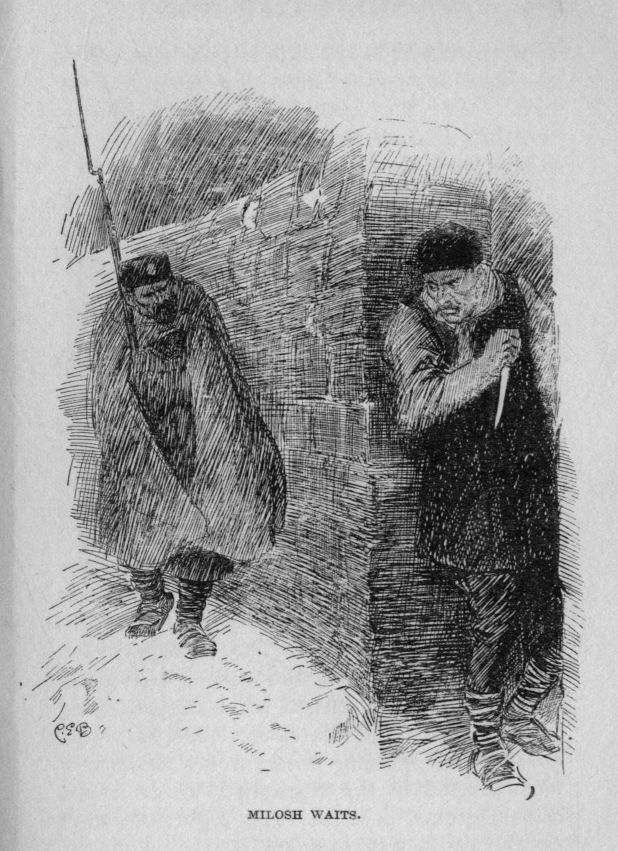

Showing what followed an accident in Macedonia

Relating an incident of trench warfare in Flanders

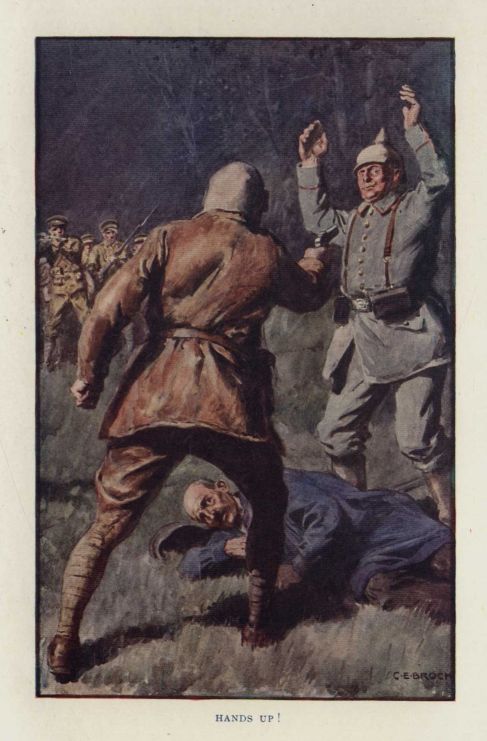

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

COLOUR PLATES

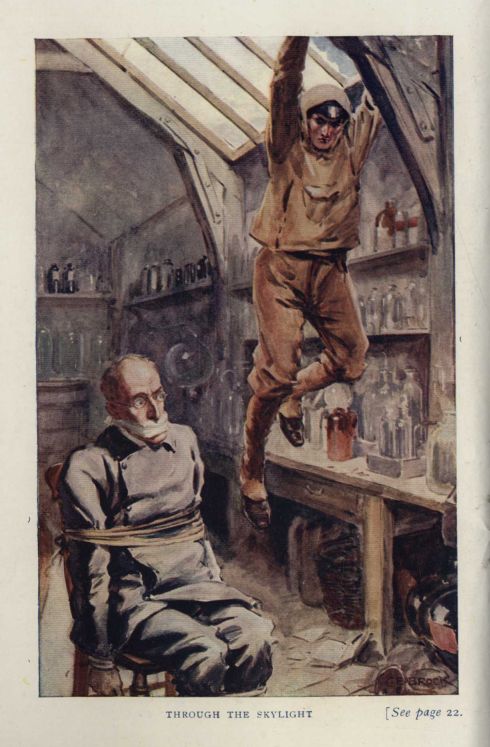

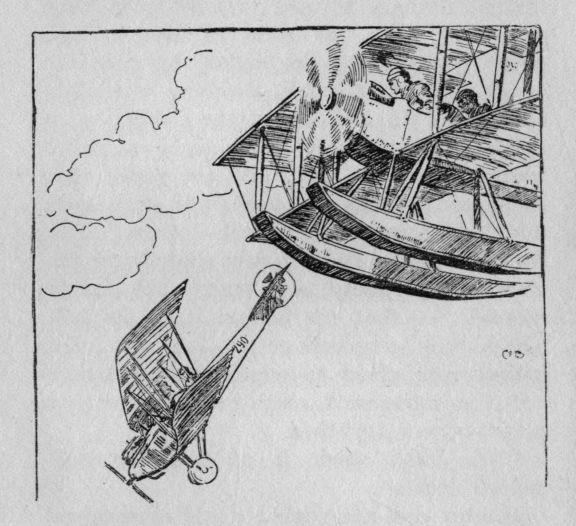

Through the Skylight . . . Frontispiece (see page 22)

DRAWINGS IN LINE

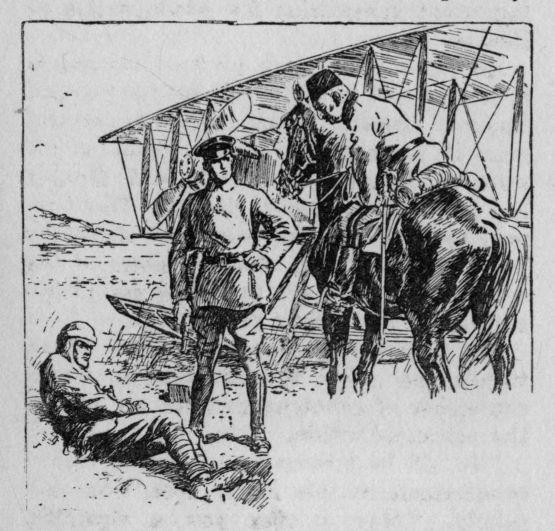

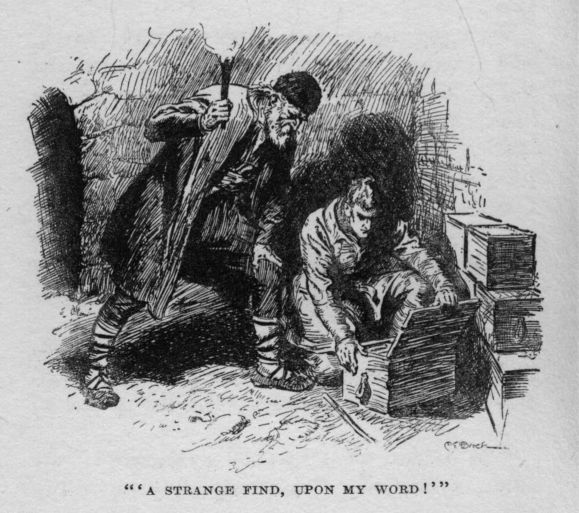

"A strange find, upon my word"

Headings on pages 9, 63, 129, 163, 246

DÉFENSE DE FUMER

I

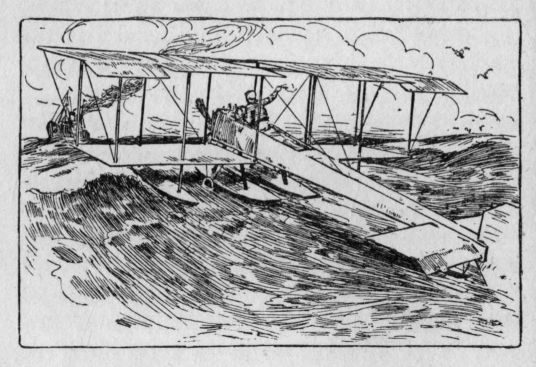

About one o'clock one Saturday afternoon in summer, a hydro-aeroplane--or, as its owner preferred to call it, a flying-boat--dropped lightly on to the surface of one of the many creeks that intersect the marshes bordering on the river Swale. The pilot, a youth of perhaps twenty years, having moored his vessel to a stake in the bank, leapt ashore with a light suit-case, and walked rapidly along a cinder path towards the low wooden shed, painted black, that broke the level a few hundred yards away.

It was a lonely spot--the very image of dreariness. All around extended the "glooming flats"; between the shed and Luddenham Church, a mile or so distant, nothing varied the grey monotony except an occasional tree, and a small red-brick, red-tiled cottage, which, with its flower-filled windows, seemed oddly out of place amid its surroundings--an oasis in a desert.

The youth, clad in khaki-coloured overalls and a pilot's cap, made straight for the open door of the shed. There he set his suit-case on the ground, and stepping in, recoiled before the acrid smell that saluted his nostrils. He gave a little cough, but the man stooping over a bench that ran along one of the walls neither looked up, nor in any way signified that he was aware of a visitor. He was a tall, fair man, spectacled, slightly bald, clean shaven, dressed in garments apparently of india-rubber. The bench was covered with crucibles, retorts, blow-pipes, test tubes, Bunsen burners, and sundry other pieces of scientific apparatus, and on the shelf above it stood an array of glass bottles and porcelain jars. It was into such a jar that the man was now gazing.

"Hullo, Pickles!" said the newcomer, coughing again. "What a frightful stink!"

The man lifted his head, looked vacantly through his spectacles for a moment, then bent again over the jar, from which he took a small portion of a yellowish substance on the end of a scalpel. Placing this in a glass bowl, he poured on it a little liquid from one of the glass bottles, stirred it with a glass rod, and watched. A smell of ammonia combined with decayed fish mingled with the other odours in the air, causing the visitor to choke again.

"Beautiful!" murmured the experimenter. He then poured some of the solution into another vessel and gazed at it with the rapt vision of an enthusiast.

Ted Burton leant against the doorpost. He knew that it was useless to interrupt his friend until the experiment was concluded. But becoming impatient as the minutes passed, he took out a cigarette, and was about to strike a match. Then, however, at a sudden recollection of his surroundings, he slipped out into the open air, taking great gulps as if to clear his throat of the sickening fumes, and proceeded to light his cigarette in ease of mind.

By and by a cheery voice hailed him from the interior.

"That you, Teddy?"

"If you've quite finished," said Burton, putting his head in at the door, after he had first flung away his half-smoked cigarette.

"Glad to see you, my dear fellow. I say, will you do something for me? You came in your machine, of course."

"Of course. What is it? It's about lunch-time, you know."

"Is it? But it won't take you long. I've run out of picric acid, and can't get on. Just fly over to Chatham, will you, and bring some back with you. You'll get it at Wells's in the High Street: you'll be there and back in half an hour or so."

"Can't you wait till after lunch?"

"Well, I can, but it will be a nuisance. You see, the whole experiment is hung up for want of the stuff."

"Oh, very well. By the way, you've done it at last, I see."

"Done what?"

"Pulled off the phenosulphonitro-something-or-other that you've been working at I don't know how long."

"How on earth did you know?" inquired his friend with an air of surprise and chagrin.

Burton pulled out a newspaper, unfolded it, and handed it over, pointing to a short paragraph.

We understand that a new high explosive of immense power, the invention of Dr. Bertram Micklewright, is about to be adopted for the British Navy. Dr. Micklewright has been for some years engaged in perfecting his discovery, and after prolonged experimentation has succeeded in rendering his explosive stable.

"Well, I'm hanged!" cried Micklewright, frowning with annoyance. "The Admiralty swore me to secrecy, and now they've let the cat out of the bag. Some confounded whipper-snapper of a clerk, I suppose, who's got a journalist brother."

"It's true, then?"

"Yes, by Jove, it's true! Look, here's the stuff; licks lyddite hollow."

He took some yellowish crystals from a porcelain bath and displayed them with the pride of an inventor.

"I say, Pickles, is it safe?" said Burton, backing as the chemist held the stuff up for his inspection.

"Perfectly," said Micklewright with a smile. "It's more difficult even than lyddite to detonate, and it'll burn without exploding. Look here!"

He put a small quantity into a zinc pan, lit a match, and applied it. A column of suffocating smoke rose swiftly to the roof. Burton spluttered.

"Beautiful!" he gasped ironically. "I'm glad, old man; your fortune's made now, I suppose. But I can't say I like the stink. Takes your appetite away, don't it?"

"Ah! You mentioned lunch. Just get me that stuff like a good fellow; then I'll prepare my solution; and then we'll have lunch and you can dispose of me as you please."

II

Burton returned to the creek, boarded his flying-boat, and was soon skimming across country on the fifteen-mile flight to Chatham.

He had been Micklewright's fag at school, and the two had remained close friends ever since. Micklewright, after carrying all before him at Cambridge, devoted himself to research, and particularly to the study of explosives. To avoid the risk of shattering a neighbourhood, he had built his laboratory on the Luddenham Marshes, putting up the picturesque little cottage close at hand for his residence. There he lived attended only by an old woman, who often assured him that no one else would be content to stay in so dreary a spot. He had wished Burton, when he left school, to join him as assistant: but the younger fellow had no love for "stinks," and threw in his lot with a firm of aeroplane builders. Their factory being on the Isle of Sheppey, within a few miles of Micklewright's laboratory, the two friends saw each other pretty frequently; and when Burton started a flying-boat of his own, he often invited himself to spend a week-end with Micklewright, and took him for long flights for the good of his health, as he said: "an antidote to your poisonous stenches, old man."

Burton was so much accustomed to voyage in the air that he had ceased to pay much attention to the ordinary scenes on the earth beneath him. But he had completed nearly a third of his course when his eye was momentarily arrested by the sight of two motor-cycles, rapidly crossing the railway bridge at Snipeshill. To one of them was attached a side car, apparently occupied. Motor-cycles were frequently to be seen along the Canterbury road, but Burton was struck with a passing wonder that these cyclists had quitted the highway, and were careering along a road that led to no place of either interest or importance. If they were exploring they would soon realise that they had wasted their time, for the by-road rejoined the main road a few miles further east.

On arriving at Chatham, Burton did not descend near the cemetery, as he might have done with his landing chassis, but passed over the town and alighted in the Medway opposite the "Sun" pier. Thence he made his way to the address in the High Street given him by Micklewright. He was annoyed when he found the place closed.

"Just like old Pickles!" he thought. "He forgot it's Saturday." But, loth to have made his journey for nothing, he inquired for the private residence of the proprietor of the store, and luckily finding him at home, made known the object of his visit.

"I'm sorry I shall have to ask you to wait, sir," said the man. "The place is locked up, as you saw; my men have gone home, and I've an engagement that will keep me for an hour or so; perhaps I could send it over--some time this evening?"

"No, I'd better wait. Dr. Micklewright wants the stuff as soon as possible. When will it be ready?"

"If you'll be at the store at three o'clock I will have it ready packed."

It was now nearly two.

"No time to fly back to lunch and come again," thought Burton, as he departed. "I'll get something to eat at the 'Sun,' and ring old Pickles up and explain."

He made his way to the hotel, a little annoyed at wasting so fine an afternoon. Entering the telephone box he gave Micklewright's number and waited. Presently a girl's voice said--

"There's no reply. Shall I ring you off?"

"Oh! Try again, will you, please?"

Micklewright often took off the receiver in the laboratory, to avoid interruption during his experiments, and Burton supposed that such was the case now. He waited; a minute or two passed; then the girl's voice again--

"I can't put you on. There's something wrong with the line."

"Thank you very much," said Burton; he was always specially polite to the anonymous girls of the telephone exchange, because "they always sound so worried, poor things," as he said. "Bad luck all the time," he thought, as he hung up the receiver.

He passed to the coffee-room, ate a light lunch, smoked a cigarette, looked in at the billiard-room, and on the stroke of three reappeared at the chemist's store. In a few minutes he was provided with a package carefully wrapped, and by twenty minutes after the hour was soaring back to his friend's laboratory.

Alighting as before at the creek, he walked up the path. The door of the shed was locked. He rapped on it, but received no answer, and supposed that Micklewright had returned to the house, though he noticed with some surprise that his suit-case still stood where he had left it. He lifted it, went on to the cottage, and turned the handle of the front door. This also was locked. Feeling slightly irritated, Burton knocked more loudly. No one came to the door; there was not a sound from within. He knocked again; still without result. Leaving his suit-case on the doorstep, he went to the back, and tried the door on that side. It was locked.

"This is too bad," he thought. "Pickles is an absent-minded old buffer, but I never knew him so absolutely forgetful as this. Evidently he and the old woman are both out."

He returned to the front of the house, and seeing that the catch of one of the windows was not fastened, he threw up the lower sash, hoisted his suit-case over the sill, and himself dropped into the room. The table was laid for lunch, but nothing had been used.

"Rummy go!" said Burton to himself.

Conscious of a smell of burning, he crossed the passage, and glanced in at Micklewright's den, then at the kitchen, where the air was full of the fumes of something scorching. A saucepan stood on the dying fire. Lifting the lid, he saw that it contained browned and blackened potatoes. He opened the oven door, and fell back before a cloud of smoke impregnated with the odour of burnt flesh.

"They must have been called away very suddenly," he thought. "Perhaps there's a telegram that explains it."

He was returning to his friend's room when he was suddenly arrested by a slight sound within the house.

"Who's there?" he called, going to the door.

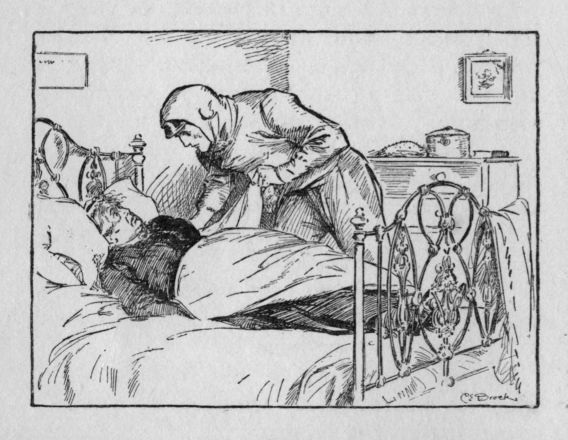

From the upper floor came an indescribable sound. Now seriously alarmed, Burton sprang up the stairs and entered Micklewright's bedroom. It was empty and undisturbed. The spare room which he was himself to occupy was equally unremarkable. Once more he heard the sound: it came from the housekeeper's room.

"Are you there?" he called, listening at the closed door.

He flung it open at a repetition of the inarticulate sound. There, on the bed, lay the old housekeeper in a huddled heap, her hands and feet bound, and a towel tied over her head. This he removed in a moment.

"Oh, Mr. Burton, sir, I'm so glad you've come," gasped the old woman; "oh, those awful men!"

"What has happened, Mrs. Jones?" cried Burton; "where's the doctor?"

"Oh, I don't know, sir. I'm all of a shake, and the mutton'll be burnt to a cinder."

"Never mind the mutton! Pull yourself together and tell me what happened."

He had cut the cords, and lifted her from the bed.

"Oh, it near killed me, it did. I was just come upstairs to put on a clean apron when I heard the door open, and some one went into the kitchen. I thought it was the doctor, and called out that I was coming. Next minute two men came rushing up, and before I knew where I was they smothered my head in the towel, and flung me on to the bed like a bundle and tied my hands and feet. It shook me all to pieces, sir."

Burton waited for no more, but leapt down the stairs, vaulted over the window sill, and rushed towards the laboratory, trembling with nameless fears. He tried to burst in the door, but it resisted all his strength. There were no windows in the walls; the place was lighted from above. Shinning up the drain-pipe, he scrambled along the gutter until he could look through the skylight in the sloping roof. And then he saw Micklewright, with his back towards him, sitting rigid in a chair.

III

Burton drove his elbow through the skylight, swung himself through the hole, and dropped to the floor. To his great relief he saw that Micklewright was neither dead nor unconscious; indeed, his eyes were gazing placidly at him through his spectacles. It was the work of a moment to cut the cords that bound the chemist's legs and arms to the chair, and to tear from his mouth the thick fold of newspaper that had gagged him.

"Wood pulp!" said Micklewright, with a grimace of mild disgust, as soon as he could speak. "Beastly stuff!--if I've got to be gagged, gag me with rag!"

"Who did it? What's it mean?" said Burton.

"It means that somebody was keenly interested in that paragraph which the Admiralty clerk so kindly supplied to his journalist brother."

"The new explosive?"

"Yes. Competitors abhor a secret.... The taste of printer's ink on pulp paper is very obnoxious, Teddy."

"Hang the paper! Tell me what happened."

"It was very neatly done. As nearly as I can recollect, a man put his head in at the door and asked politely, but in broken English, the way to Faversham. Being rather busy at the time I'm afraid I misdirected him. But it didn't matter, because a second or two after I was kicking the shins of two other fellows who were hugging me; I'm sorry I had to use my boots, but my fists were not at the moment available. You see how it ended.

"They had just fixed me in the chair--printer's ink is very horrid--when the telephone bell rang. My first visitor told one of the others, in French, to cut the wire: it must have been rather annoying to the person at the other end."

"I was trying to get you in the 'Sun.' But go on."

"Their next movements much interested me. The commander of the expedition began to scout along the bench, and soon discovered my explosive--by the way, I proposed to call it Hittite. He was a cool card. He first burnt a little: 'Bien!' said he. Then he exploded a little: 'Bien!' again. Then he scooped the whole lot into a brown leather bag, just as it was, and made off, lifting his hat very politely as he went out. He had some trouble in getting his motor-cycle to fire----"

"They came on motor-cycles? I saw two crossing the railway at Snipeshill as I went. Look here, Pickles, this is serious, isn't it?"

"Well, of course any fool could make Hittite after a reputable chemist has analysed my stuff. I shall have to start again, I suppose."

"Great Scott! How can you take it so coolly? The ruffians have got to be caught. Can you describe them?"

"Luckily, they allowed me the use of my eyes, though I've heard of speaking eyes, haven't you? They were all foreigners. The commander was a big fellow, bald as an egg, with a natty little moustache, very urbane, well educated, to judge by his accent, though you can never tell with these foreigners. The others were bearded--quite uninteresting--chauffeurs or mechanics--men of that stamp. Their boss was a personality."

"He spoke French?"

"Yes. You brought that picric acid, Teddy?"

"It's in the house. By the way, they gagged Mrs. Jones too."

"Not with a newspaper, I hope. I'm afraid the poor old thing will give me notice. We had better go and console her."

They mounted on the bench, clambered thence through the skylight, and slid to the ground.

"Look here, Pickles," said Burton, as they went towards the house, "I'm going after those fellows. Being foreigners they are almost sure to have made for the Continent at once. I'll run down to the road and examine the tracks of their cycles; you've got an ABC in the house?"

"It is possible."

"Well, hunt it out and look up the boats for Calais. How long have they been gone?"

"Perhaps three-quarters of an hour."

"A dashed good start!" exclaimed Burton. "We'll save time if you bring the ABC down to the creek. Buck up, old chap; no wool-gathering now, for goodness' sake."

They parted. A brief examination of the tracks assured Burton that the cyclists had continued their journey eastward. They would probably run into the highroad to Dover somewhere about Norton Ash. Returning to the creek he was met by Micklewright with the buff-coloured timetable. Micklewright was limping a little.

"There's no Calais boat at this time of day," he said.

"Did you try Folkestone?"

"It didn't occur to me."

Burton took the time-table from him and turned over the pages rapidly.

"Here we are: Folkestone to Boulogne, 4.10. It's now 3.35," said Burton, looking at his watch. "I can easily get to Folkestone in half an hour or less--possibly intercept the beggars if they don't know the road: in any case be in time to put the police on before the boat starts. You'll come, Pickles?"

"Well, no. I strained a muscle or two in scuffling with those gentlemen--and I've had nothing but newspaper since eight o'clock. By the way, you may as well take the only clue we have--this scrap of pulp. It is French, as you see. And, Teddy, don't get into hot water on my account. The resources of civilisation--as expressed in high explosives--are not exhausted."

Burton stuffed the newspaper into his pocket, and in three minutes was already well on the way to Folkestone. Micklewright watched the flying-boat until it was lost to sight; then, pressing his hand to his aching side, he returned slowly to the house.

The distance from the Luddenham Marshes to Folkestone is about twenty-five miles as the crow flies, and Burton had made the flight once in his flying-boat. Consequently, he was at no loss in setting his course. A brisk south-west wind was blowing, but it very little retarded his speed, so that he felt pretty sure of reaching the harbour by four o'clock. Keeping at an altitude of only a few hundred feet, he was able to pick up the well-known landmarks: Hogben's Hill, the Stour, the series of woods lying between that river and the Elham valley railway line; and just before four he alighted on the sea leeward of the pier, within a few yards of the steamer.

A small boat took him ashore. He avoided the crowd of holiday makers who had already gathered to watch him, and making straight for the pier, accosted a police inspector.

"Have you seen three men ride up on motor cycles, inspector?" he asked.

"No, sir, I can't say I have."

"Three foreigners, one a tall big fellow?"

"Plenty of foreigners have gone on board, sir. Is anything wrong?"

"Yes, they've assaulted and robbed a friend of mine--you may know his name: Dr. Bertram Micklewright, the inventor. They've stolen Government property, and it's of the utmost importance to prevent their crossing the Channel."

"Where did this take place, sir, and at what time?"

"At Luddenham Marshes beyond Faversham, just before three o'clock."

"They'd hardly have got here, would they? They'd have to come through Canterbury, between thirty and forty miles, and with speed limits here and there they'd only just about do it."

"I'll wait here, then. You'll arrest them if they come?"

"That's a bit irregular, sir," said the inspector, rubbing his chin. "You saw them do the job?"

"Well, no, I didn't."

"Then you can't be sure of 'em?"

"I'm afraid I can't, but there wouldn't be two sets of foreigners on motor cycles. You could detain them on suspicion, couldn't you?"

"I might, if you would take the responsibility."

"Willingly. I'll keep a look-out then."

It occurred to Burton that the men might leave the cycles and approach on foot, so he closely scrutinised all the passengers of foreign appearance who passed on the way to the boat. None of them answered to Micklewright's description.

"Haven't you got any clue to their identity, sir?" asked the inspector, who remained at his side.

"None; it happened during my absence. They tied up my friend and gagged him. I came across country in my flying machine yonder."

"They'll lose this boat for certain," said the inspector, as the steamer's warning siren sounded. "You're sure they are Frenchmen?"

"Yes; well, they left a French newspaper behind them."

"Do you happen to have it with you?"

Burton drew the crushed paper from his pocket, and handed it to the policeman, who unfolded it, and displayed a torn sheet, with only the letters IND remaining of the title.

"That's the Indépendance Belge," said the inspector at once. "I expect they're Belgians, and aren't coming here at all. Ostend's their mark, I wouldn't mind betting."

"Via Dover, of course. Is there a boat?"

"One at 4.30, sir. I'm afraid they've dished you."

"I'm not so sure about that," said Burton, glancing at his watch. "It's now 4.20; this boat's off. If the Ostend boat is ten minutes late too I can get to Dover in good time to have it searched."

"Then if I were you I'd lose no time, sir, and I hope you'll catch 'em."

Burton raced back to the boat that had brought him ashore. In five minutes he was on his own vessel, in two more he was in full flight before the favouring wind, and at 4.35 he dropped on the water in the lee of the Admiralty pier at Dover. But he had already seen that he was too late. The boat, which had evidently started on time, was at least half a mile from the pier.

"Yes, sir, I did see a big foreigner go on board at the last minute," said the policeman of whom Burton inquired ten minutes later. "He was carrying a small brown leather hand-bag. I took particular note of him, because he blowed like a grampus, and took off his hat to wipe his head, he was that hot."

"Was he bald?"

"As bald as the palm of your hand. A friend of yours, sir?"

"No," said Burton emphatically. "He's got away with a secret worth thousands of pounds--millions perhaps, to a foreign navy."

The policeman whistled.

IV

Burton stood looking at the diminishing form of the steamboat. The constable touched his sleeve.

"You see that gentleman there, sir?" he said.

Following his glance, Burton saw a slim youthful figure, clad in a light tweed suit and a soft hat, leaning over the rail.

"Well?" he asked.

The constable murmured a name honoured at Scotland Yard.

"Put the case to him, sir," he added; "he can see through most brick walls." Burton hastened to the side of the detective.

"A man on that boat has stolen the secret of the new explosive for the British Navy," he said without preamble. "Can you stop him?"

The detective turned his keen eyes on his questioner and looked hard at him for a moment or two.

"Tell me all about it, sir," he said.

Burton hurriedly related all that had happened. "A cable to Ostend would be enough, wouldn't it?" he asked in conclusion.

"I'm afraid it would hardly do, sir," replied the detective. "Your description is too vague. Tall man about forty, bald, with a hand-bag--there may be dozens on the boat. It would be too risky. We have to be careful. I saw a notorious diamond thief go on board, but I couldn't arrest him, not having a warrant, and nothing certain to go upon. You had better go to the police station, tell the superintendent all you know, and leave him to communicate with the Belgian police in due course."

"And give the thief time to get rid of the stuff! If it once passes from his hands the secret will be lost to us, and any foreign Power may be able to fill its shells with Dr. Micklewright's explosive. It's too bad!"

He looked with bitter disappointment at the steamer, now a mere speck on the surface of the sea. Suddenly he had an idea.

"If I got to Ostend first," he said, "I could have the man arrested as he lands?"

The detective smiled.

"I don't think the Belgian police would make an arrest on the strength of your story, sir," he said. "Why, you can't even be sure your man is aboard. Arresting the wrong party might be precious awkward for you and everybody."

"I'll risk that," cried Burton. "It's my funeral, any way."

"That little machine of yours is safe, I suppose, sir? It won't come down and bury you at sea?"

"No fear!" said Burton with a smile. "Still, in case of accidents, here's my card. All I ask is, don't give anything away to newspaper men for a couple of days, at any rate. It's to a newspaper man we owe the whole botheration."

"All right, sir; I'll give you a couple of days. I wish you luck."

Burton hurried to one of the small boats lying for hire alongside the pier, and was put on board his own vessel. He started the motor, but in his haste he failed to pull the lever with just that knack that jerks the floats from the surface. At the second attempt he succeeded, and the water-plane rose into the air as smoothly as a gull. The steamer was now out of sight, but he had a general idea of her direction, and hoped by rising to a good altitude soon to get a glimpse of her. The wind had freshened, and time being of the utmost importance, Burton congratulated himself on the possession of a Clift compass, by means of which he could allow for drift, and avoid fatal error in setting his course. The steamer had nearly an hour's start, but as he travelled at least twice as fast, he expected to overhaul her in about an hour if he did not mistake her direction.

His mind was busy as he flew. He had to admit the force of what the detective had said. It would almost certainly be difficult to induce the Belgian police to act on such slight information as he could give them; and in the bustle of landing, the criminal, of whose identity he could not be sure, might easily get away. Burton was beginning to feel that he had started on a wild-goose chase when, catching sight of the smoke of the vessel some miles ahead, he suddenly, without conscious reasoning, determined on his line of action. Such flashes sometimes occur at critical moments.

Waiting for a few minutes to make sure that the distant vessel was that in which he was interested, he bore away to the east, instead of following directly the track of the steamer. It was scarcely probable that the flying-boat had already been noticed from the deck. He described a half-circle of many miles, so calculated that when he approached the vessel it was from the east, at an angle with her course.

He was still at a considerable height, and as he passed over the vessel his view of the deck was obscured by the cloud of black smoke from her funnels. In a few seconds he wheeled as if to return on his track; but soon after recrossing the steamer he wheeled again, and making a steep volplané, alighted on the sea about half a mile ahead. Then with his handkerchief he began to make signals of distress. There was a considerable swell on the surface, and it might well have seemed to those on board the steamer who did not distinguish the flying-boat from an aeroplane that the frail vessel was in imminent danger.

The steamer's helm was instantly ported; she slowed down and was soon alongside. A rope was let down by which Burton swung himself to the deck; and while he struggled through the crowd of excited passengers who clustered about him, the flying-boat was hoisted by a derrick, and the vessel resumed its course.

Burton made his way to the bridge to interview the captain.

"I'm very much obliged to you, sir," he said. "And I'm very sorry to have delayed you. My engine stopped."

"So did mine," returned the captain, with a rather grim look about the mouth, "or rather, I stopped them." Burton did not feel called upon to explain that his stoppage also had been voluntary. "And I shall have to push them to make up for the twenty minutes we have lost. You would not have drowned; I see your machine floats; but you might have drifted for days if I hadn't picked you up."

"It was very good of you," said Burton, feeling sorry at having had to practise a deception. "It's my first voyage across Channel. I started from Folkestone; better luck next time. I must pay my passage, captain."

"Certainly not," said the captain. "I won't take money from a gallant airman in distress. I have a great admiration for airmen; they run double risks. I wouldn't trust myself in an aeroplane on any account whatever."

Burton remained for some minutes chatting with the captain, then descended to the deck in search of his quarry, to be at once surrounded by a group of first-class passengers, who plied him with eager questions about his starting-point, his destination, and the nature of the accident that had brought him down. He answered them somewhat abstractedly, so preoccupied was he with his quest. His eyes roamed around, and presently he felt an electric thrill as he caught sight, on the edge of the crowd, of a tall portly figure that corresponded, he thought, to Micklewright's brief description. The man had a round red face, with a thick stiff moustache upturned at the ends. His prominent blue eyes were fixed intently on Burton. He wore a soft hat, and Burton, while replying to a lady who wanted to know whether air-flight made one sea-sick, was all the time wondering if the head under the hat was bald.

Disengaging himself by and by from those immediately around him, he edged his way towards this stalwart passenger. It gave him another thrill to see that the man held a small brown leather hand-bag. He felt that he was "getting warm." No other passenger carried luggage; this bag must surely contain something precious or its owner would have set it down. Burton determined to get into conversation with him, though he felt much embarrassed as to how to begin. The blue eyes were scanning him curiously.

"I congratulate you, sir," said the foreigner in English, politely lifting his hat. Burton almost jumped when he saw that the uncovered crown was hairless.

"Thank you, sir," he replied, in some confusion. "It was lucky I caught the boat."

As soon as the words were out of his mouth, he thought, "What an idiotic thing to say!" and his cheeks grew red.

"Zat ze boat caught you, you vould say?" said the foreigner, smiling. "But your vessel is a hydro-aeroplane, I zink so? Zere vas no danger zat you sink?"

"Well, I don't know. With a swell on, like this, it wouldn't be any safer than a cock-boat; and in any case, it wouldn't be too pleasant to drift about, perhaps for days, without food."

"Zat is quite right; ven ze sea is choppy, you feed ze fishes; ven it is calm, you have no chops. Ha! ha! zat is quite right. You do not understand ze choke?" he added, seeing that Burton did not smile.

"Oh yes! yes!" cried Burton, making an effort. "You speak English well, sir."

"Zank you, yes. I have practised a lot. I ask questions--yes, and ven zey ask you chust now vat accident bring you down, I do not quite understand all about it."

"It was quite an ordinary thing," said Burton, rather uncomfortably. The explanation he had given to the questioners was vague; he was loth to tell a deliberate lie. "Do you know anything about petrol engines, sir?"

"Oh yes, certainly. I ride on a motor-bicycle. One has often trouble viz ze compression."

"That's true," said Burton, feeling "warmer" than ever. The foreigner was evidently quite unsuspicious, or he would not have mentioned the motor-cycle. "We have excellent roads in England," he added, with a fishing intention.

"Zat is quite right; but zey are perhaps not so good as our roads in France, eh?"

"Your roads are magnificent, it's true; still--what do you say to the Dover Road?"

"Ah! Ze Dover Road; yes, it is very good, ever since ze Roman times, eh? Yes; I have travelled often on ze Dover Road, from Dover to Chatham, and vice versa. Viz zis bag!"

Burton looked hard at the bag. He wished it would open. One peep, he was sure, would be enough to convict this amiable Frenchman.

"I have somezink in zis bag," the Frenchman went on in a confidential tone--"somezink great, somezink magnificent,--éclatant as we say; somezink vat make a noise in ze vorld."

He tapped the bag affectionately. Burton tingled; he would have liked to take the man by the throat and denounce him as a scoundrel. But perhaps if he were patient the confiding foreigner would open the bag.

"Indeed!" he said.

"Yes; a noise zat shall make ze hair stand on end. Ha! ha! Ah! you English. You are ze great inventors. Your Sims, your Edvards, your Rowland--ah! zey are great, zey are honoured by all ze crowned heads in ze vorld. Zat is quite right! I tell you! ... No; it is late. You shall be in Ostend, sir?"

"Yes."

"Zen you shall see, you shall hear, vat a great sensation I shall make. Now it gets dark; if you shall pardon me, I vill take a little sleep until ve arrive. Zen!..."

He lifted his hat again, and withdrew to a deck chair, where he propped the bag carefully under his head and was soon asleep.

V

Burton strolled up and down the deck, impatient for the boat to make the port. He was convinced: the man was French; he was tall, urbane, and bald; he rode a motor-cycle; he knew the Dover Road; he guarded his bag as something precious, and it contained something that was going to make a noise in the world. What so likely to do that as Micklewright's explosive!

One thing puzzled Burton; the man's allusion to English inventors--Sims, Edwards, Rowland--who were they? Burton subscribed to a good many scientific magazines, and kept closely in touch with recent inventions; but he did not recall any of these names. It flashed upon him that the Frenchman, rendered suspicious by his fishing questions, had mentioned the names as a blind; he had spoken of Sims, Edwards and Rowland when his mind was really full of Micklewright.

"If that's your game, it won't wash," he thought.

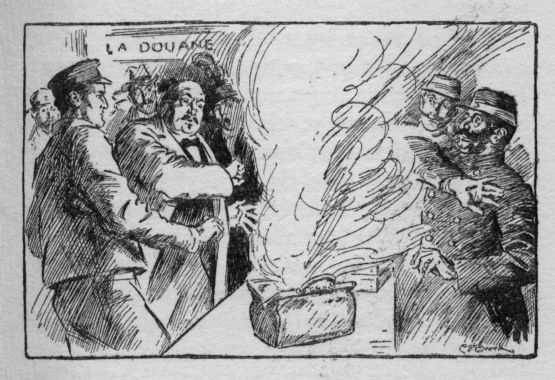

He determined, as soon as the vessel reached port, to hurry ashore, interview the Customs officers, and warn them in general terms of the dangerous nature of what the Frenchman carried. If only the bag had been opened and its contents revealed, he would not have hesitated to inform the captain, and have the villain detained. But the Customs officers, primed with his information, would insist on opening the bag, and then!--yes, there would undoubtedly be "a noise in the world," when it became known that so audacious a scheme had been detected and foiled.

The sun went down, the steamer plugged her way onward, and through the darkness the lamps of Ostend by and by gleamed faintly in the distance. Burton made his way to the bridge again, and asked the captain to allow the flying-boat to remain on the vessel till the morning; then he returned to the deck, and leant on the rail near the gangway.

All was bustle as the steamer drew near to the harbour. The passengers collected their belongings, and congregated. Some spoke to Burton; he hardly heeded them. He had his eye on the Frenchman, still slumbering peacefully.

The bells clanged; the vessel slowed; a rope was thrown to the pier; and two of the sailors stood ready to launch the gangway as soon as the boat came to rest. The moment it clattered on to the planks of the pier Burton was across, and hurried to the shed where the Customs officers, like spiders in wait for unwary flies, were lined up behind their counter, cool, keen, alert. He accosted the chief douanier, described the Frenchman in a few rapid sentences, suggested that the brown bag would repay examination, and receiving assurance that the proper inquiries should be made, posted himself outside at the corner of the shed in the dark, to watch the scene.

The passengers came by one by one, and answering the formal question, had their luggage franked by the mystic chalk mark and passed on. Burton's pulse throbbed as he saw the tall Frenchman come briskly into the light of the lamps.

"Here he is!" whispered the officers one to another.

"Have you anything to declare, monsieur?" asked one of them, with formal courtesy.

"No, no, monsieur," replied the man; "you see I have only a hand-bag."

He laid it on the counter to be chalked.

"Be so good as to open the bag, monsieur," said the officer.

The Frenchman stared; the passengers behind him pricked up their ears as he began to expostulate in a torrent of French too rapid for Burton to follow. The officer shrugged, and firmly repeated his demand. Still loudly protesting, the Frenchman drew a bunch of keys from his pocket, selected one, and with a gesture of despair laid open the bag to the officer's inspection.

Burton drew a little nearer and watched feverishly. The officer put his hand into the bag, and drew forth a bundle of what appeared to be striped wool. Exclaiming at its weight, he laid it on the counter, and began to unroll it. His colleagues smiled as he held aloft the pantaloons of a suit of pyjamas. He threw them down, and took up the object round which the garment had been wrapped. It was a large glass bottle, filled with a viscid yellowish liquid, and bearing a label.

"Voila!" shouted its owner. "Je vous l'avais bien dit."

The officer took up the bottle, eyeing it suspiciously. He examined the label; he took out the stopper and sniffed, then held the bottle to the noses of his colleagues, who sniffed in turn.

"It will not explode?" he said to the Frenchman.

"Explode!" snorted the man scornfully. "It is harmless; it is perfect; it contains no petroleum; look, there is the warranty on the label. Bah!"

He struck a match and held it to the mouth of the open bottle, which the officer extended at arm's length. The flame flickered and went out.

"Voila!" said the Frenchman with a triumphant snort.

Then fumbling in his pocket he drew out a sheaf of flimsy papers. One of these he handed to the officer, who glanced at it, smiled, said, "Ah! oui! oui!" and replacing the stopper, rolled the bottle in the pyjamas again.

"But it is not yet certain," he exclaimed. "Monsieur will permit me."

He plunged his hand again into the bag, whose owner made a comical gesture of outraged modesty as the officer brought out, first the companion jacket of the pantaloons, then a somewhat ancient tooth-brush. He rummaged further, turned the bag upside down. It contained nothing else.

"A thousand excuses, monsieur," he said, replacing the articles, and chalking the bag.

"Ah! It is your duty," said the passenger magnanimously. "Good-night, monsieur."

Catching sight of Burton as he was passing on, he stopped.

"Ah! my friend, here you are," he said. "I give you vun of my announce. It has ze address. I see you to-morrow? Zat is quite right!"

Then he lifted his hat and went his way.

Burton thrust the slip of paper into his pocket without looking at it. He felt horribly disconcerted. The fluid in the bottle was certainly not Micklewright's explosive; that was a crystalline solid. He had made an egregious mistake. It was more than disappointing; it was humiliating. He had been engaged in a wild-goose chase indeed. His stratagem was wasted; his suspicions were unfounded; his deductions utterly fallacious. While he was dogging this innocent Frenchman, the real villain was no doubt on the other side of the sea, waiting for the night boat from Dover or perhaps Newhaven. He had made a fool of himself.

Despondent and irritated, he was about to find his way to the nearest hotel for the night, when he suddenly noticed a second portly figure approaching the shed among the file of passengers. The man was hatless; he was bald; he carried a brown leather hand-bag. His collar was limp; his face was clammy, and of that pallid greenish hue which betokens beyond possibility of doubt a severe attack of sea-sickness.

At the first glance Burton started; at the second he flushed; then, on the impulse of the moment, he sprang forward, and reaching the side of the flabby passenger at the moment when he placed his bag upon the counter, he laid his hand upon it, and cried--

"My bag, monsieur!"

The bald-headed passenger glanced round in mere amazement, clutching his bag.

"Excuse me, monsieur," he said quietly, "it is mine."

The Customs officer looked from one to the other: the pallid foreigner, limp and nerveless; the ruddy Englishman, eager, strenuous and determined.

"Ah! You gave me the warning. You were mistaken," he said to Burton. "The other bag contained only pyjamas, a bottle, and a toothbrush; nothing harmful. Monsieur is too full of zeal; he may be mistaken again. He accuses this gentleman of stealing his bag? Well, that is a matter for the police. I will do my duty, then you can find a policeman. Have you anything to declare?" he concluded in his official tone.

"Nothing," said the foreigner.

"A thousand cigarettes!" cried Burton at the same moment.

Each had still a hand on the bag. At Burton's words the passenger gave him a startled glance, and Burton knew by the mingled wonder and terror in his eyes that this time he had made no mistake.

"Comment! A thousand cigarettes!" repeated the officer. "Messieurs must permit me to open the bag."

He drew it from their grasp. It opened merely by a catch. The officer peeped inside, and shot a questioning look at Burton, who bent over, and at a single glance recognised the small yellowish crystals.

"That's it!" he cried in excitement.

"Monsieur will perhaps explain," said the officer to the owner of the bag, who appeared to have become quite apathetic. "There are no cigarettes; no; but what is this substance? Is it on the Customs schedule? No. Very well, I must impound it for inquiry."

The man, almost in collapse from weakness, began to mumble something. The officer's remark about impounding the stuff disturbed Burton. If it got into expert hands Micklewright's secret would be discovered.

Acting on a sudden inspiration, he took a cigarette from his case, and struck a match.

"Eh, monsieur, it is forbidden to smoke," cried the officer sternly.

At the same time he nodded his head towards the placard "Défense de fumer" affixed to the wall.

"Ah! Pardon! Forbidden! So it is," said Burton, who was shading the lighted match within his rounded palm from the wind. He made as if to throw it away, but with a dexterous cast dropped it flaming into the open bag. Instantly there was a puff and whizz, and a column of thick suffocating smoke spurted up to the roof. The officer started back with an execration. A lady shrieked; others of the passengers took to their heels. The air was full of pungent fumes and lurid exclamations, and in the confusion the owner of the bag quietly slipped away into the darkness. Burton stood his ground. His task was done. Every particle of Micklewright's explosive that had left the shores of England was dissipated in gas. The secret was saved.

Choking and spluttering the officer dashed forward, shaking his fist in Burton's face, mingling terms of Gallic abuse with explosive cries for the police. A gendarme came up.

"I give him in charge," shouted the officer, with gesticulations. "It is forbidden to smoke; see, the place is full of smoke! The other man; where is he? It is a conspiracy. They are anarchists. Arrest the villain!"

"Monsieur will please come with me," said the gendarme, touching Burton on the sleeve.

"All right," said Burton cheerfully. "I can smoke as we go along?"

"It is not forbidden to smoke in the streets," replied the gendarme gravely.

And with one hand on the prisoner's arm, the other carrying the empty bag, he set off towards the town.

VI

Two evenings later, Burton descended on the creek in the Luddenham Marshes, and hastened with lightsome step to Micklewright's laboratory. It was the time of day when Micklewright usually ceased work and went home to his dinner.

"Still at it!" thought Burton, as he saw that the laboratory door was open.

He went on quickly and looked in. Micklewright was bending over his bench in his customary attitude of complete absorption.

"Time for dinner, old man," said Burton, entering.

"Hullo! That you! Come and look at this."

"Upon my word, that's a cool greeting after I've been braving no end of dangers for your sake."

"What's that you say? Look at this, Teddy; isn't it magnificent!"

Burton looked into the bowl held up for his inspection, and saw nothing but a dirty-looking mixture that smelt rather badly.

"You see, it's like this," said Micklewright, and went on to describe in the utmost technical detail the experiment upon which he had been engaged. Burton listened with resignation; he knew by experience that it saved time to let his friend have his talk out.

"Magnificent! I take your word for it," he said, when Micklewright had finished his description. "But look here, old man, doesn't it occur to you to wonder where I've been?"

"Why should it?" asked Micklewright in unaffected surprise. He looked puzzled when Burton laughed; then remembrance dawned in his eyes. "Of course; I recollect now. You went after those foreigners. I had almost forgotten them."

"Forgotten the beggars who had stolen your secret?" cried Burton.

"Hittite! Well, you see, it was gone; no good pulling a long face over it, though it was a blow after three years' work. I groused all day Sunday, but recognised it as a case of spilt milk, and this morning started on a new tack. I'm on the scent of something else. Whether it will be any good or not I can't say yet."

"Surely you got detectives down?"

"Well, no, I didn't. It's much the best to keep such things quiet. The fellows had got away with the stuff, and before the police could have done anything they'd be out of reach. So I just buckled to."

"Very philosophic of you!" said Burton drily. "I needn't have put myself about, then. Well, hand over fifty francs, and I'll cry quits."

"Fifty--francs, did you say? Won't shillings do?"

"No; I was fined in francs. I won't take advantage of you."

"I seem to be rather at sea," said Micklewright. "Have the French started air laws, and you broken 'em and been nabbed? But what were you doing in France?"

"Come and let's have some dinner," said Burton, putting his arm through his friend's. "I'm sure you don't eat enough. Any one will tell you that want of proper grub makes you dotty."

Micklewright locked up the laboratory, and went on with Burton to the house. Burton found his suit-case in the spare room and was glad to make a rapid toilet and change of clothes. In twenty minutes he was at one end of the dining-table, facing Micklewright at the other, and old Mrs. Jones was carrying in the soup. Burton waited, before beginning his story, until Micklewright had disposed of an excellent steak, and "looked more human," as he said; then--

"Since I saw you last, I've been to Ostend," he began.

"Jolly good oysters there," said Micklewright.

"Ah! You're sane at last! I didn't go for oysters, though; I went for--Hittite."

"You don't mean to say----" cried Micklewright.

"Don't be alarmed," Burton interrupted. "There's none there now. Just listen without putting your spoke in, will you!"

He related the incidents of his flights to Folkestone and Dover, his pursuit of the steamer, and the trick by which he had been taken on board.

"And then I made an ass of myself," he continued. "But it's owing--partly at any rate--to your lucid description, Pickles. Tall, stout, bald, moustache, brown bag; all the details to a T. I got into conversation with the man, and when it turned out that he was a motor-cyclist, knew the Dover Road, and had something in his bag that was going to make a noise in the world, I made sure I'd got the right man.

"You can imagine how sold I felt when, after persuading the Customs fellows to insist on opening his bag, all they fished out was a suit of pyjamas, an old toothbrush, and a bottle full of a custardy-looking stuff. He was very good-tempered about it--much more than I should have been if my wardrobe had been exposed. I was feeling pretty cheap when another fellow came along, whom your description fitted equally well, though he wasn't a scrap like the first man. He had evidently been horribly sea-sick; had gone below, I suppose, which was the reason why I hadn't seen him before. The wind had carried away his hat, and his bald pate betrayed him. I got his bag opened; had to pretend that it was mine, and full of cigarettes; and your stuff being loose in the bag it went up with a fine fizz when I dropped a match into it. That's why you owe me fifty francs. They lugged me off to the police station, and next day fined me fifty for smoking on forbidden ground, though, as I pointed out, I hadn't done any smoking, and they ought really to have fined the fellow who had the stuff in his bag. They were very curious as to what that was, but of course I didn't give it away. And it's rather rotten to find that after all you don't care a copper cent!"

"Not at all, my dear chap; I'm extremely grateful to you. I only hope you won't ruin me."

"Ruin you! What do you mean?"

"Well, you see, with Hittite safe, I shall be so sickening rich that I am almost bound to get lazy."

"If that's your trouble, just hand it over to me; I don't mind being rich, though I'm not an inventor. But I say, Pickles, that reminds me: do you know any inventors of the names of Sims, Edwards and--what was the other?--Rowland?"

"Can't say I do. Why?"

"Why, the wrong man--the bottle man, you know--gassed about the greatness of our English inventors, and mentioned these three specially, to put me off the scent, I thought. Of course his talk of inventors made me all the more sure that he had your stuff in his bag."

"Well, I can't recall any of them. Sims--you've never heard me talk of any one named Sims, have you, Martha?" he asked of the housekeeper, who entered at this moment with the coffee.

"No, sir; though if you don't mind me saying so, I've been a good mind to name him myself this long time, only I didn't like to be so bold."

"My dear good woman, what are you driving at?" asked Micklewright in astonishment.

"Why, sir, I dare say busy gentlemen like yourself don't notice it till some one tells 'em, their combs and brushes being kept tidy unbeknownst; but the truth is, I've been worriting myself over that--I reelly don't like to mention it, but there, being old enough to be your mother--I mean, sir, that little bald spot jest at the crown of the head, sir--jest at the end of the parting, like."

Micklewright laughed as he put his hand on the spot.

"Well, but--Sims?" he said.

"Well, sir, it didn't ought to be there in a gentleman of your age, and thinks I to myself: 'Now, if only the master would try one of them hair-restorers he might have his locks back as luxurious as ever they was.' And I cut the particklers out of that Strand magazine you gave me, sir, and how to choose between 'em I don't know, they're all that good. There's Edwards' Harlene for the Hair, and Rowland's antimacassar oil, and Tatcho, made by that gentleman as writes so beautiful in the Sunday papers; he's the gentleman you mean, I expect--George R. Sims."

The men shouted with laughter, and Mrs. Jones withdrew, happy that her timid suggestion had given no offence.

"To think of you in pursuit of a hairdresser gives me great joy," said Micklewright presently. "He must have been a hairdresser, Teddy."

"I suppose he was," assented Burton rather glumly. "By the way"--he felt in his pockets. "He gave me a handbill; I didn't look at it at the moment; it's in the pocket of my overall, of course. I'll fetch it."

He returned, smoothing the crumpled slip of paper, and smiling broadly.

"Here you are," he said. "'Arsène Lebrun, artist in hair, having returned from London with a marvellous new specific for promoting a luxuriant vegetation'--I am translating, Pickles--'on the most barren soil, respectfully invites all gentlemen, especially those with infantine heads'--that's very nice!--'to assist at a public demonstration on Sunday, August 20. Arsène Lebrun will then massage with his fructifying preparation the six most vacant heads in Ostend, and lay the seeds of a magnificent harvest, which he will subsequently have the honour to reap.' Hittite isn't in it with that, old man."

At this moment there was a double knock at the door, and Mrs. Jones soon re-entered with a letter.

"From the Admiralty," said Micklewright, tearing open the envelope. "Listen to this, Teddy."

"'I am directed by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to say that they are prepared to pay you £20,000 for the formula of your new explosive, and a royalty, the amount of which will be subsequently arranged, on every ton manufactured. They lay down as a peremptory condition that the formula be kept absolutely secret, and that the explosive be supplied exclusively to the British navy. I shall be glad if you will intimate your general agreement with these terms.'"

"Congratulations, old boy!" cried Burton heartily, grasping his friend's hand. "It's magnificent!"

"I really think you are right, and as it's very clear that but for you I shouldn't have been able to accept any terms whatever, it's only fair to----"

"Nonsense!" Burton interrupted. "All I want is fifty francs, for illicit smoking--a cheap smoke, as it turns out."

"Can't do it, my boy. Wait till I get my Lords Commissioners' cheque."

A week or two later, Burton's firm received an order from Dr. Micklewright for a water-plane of the best type, with all the latest improvements in canoe floats, and the finest motor on the market. When the machine was ready for delivery, Micklewright paid a visit to the factory.

"It's a regular stunner, old man," said Burton, as he explained its points to his friend.

"Well, Teddy, do me the favour to accept it as a birthday present--a little memento of your trip to Ostend."

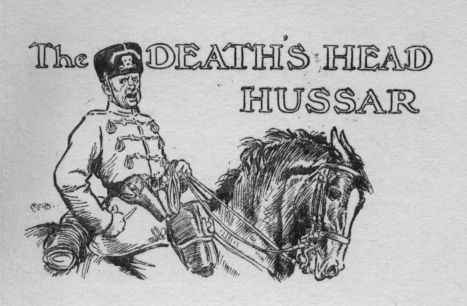

The DEATH'S HEAD HUSSAR

I

"My compliments, Burton! You brought her down magnificently," said Captain Rolfe. "Not much damage done, I hope?"

The airman stooping over the engine grunted. In a moment or two a grimy face was upturned, the tall figure straightened itself, and a crisp voice said ruefully--

"Magneto smashed to smithereens!"

He passed round to the side of the machine, and retailed at short intervals the items of a catalogue of damage.

"A stay cut! ... Two holes in the upper plane! ... Four in the lower! ... Chips and dents galore! Still, we can fall back on the old wife's consolation: it might have been worse."

"All the same, it's precious awkward," said Captain Rolfe, putting his finger through a hole in the lower plane. "The Bosches will be here in ten minutes."

"Not under twenty. They've some difficult country to cross. But, of course, there's no time to lose. It's lucky there's a village close by."

Edward Burton, airman, with Captain Rolfe, who accompanied him as observer, had just made an enforced volplané and landed safely after running the gauntlet of German rifles and machine guns. At the moment when he was flattering himself on being out of range, a shell burst close beside the machine, bespattering it with bullets and putting the engine out of action.

Rolfe had seen cavalry galloping in their direction. The sudden descent would apprise the enemy of what had happened. Whether in ten minutes or in twenty, there was no doubt that the arrival of the Germans would place the airmen in a tight corner.

The first thought of the trooper is for his horse. The airman is concerned for the state of his aeroplane. It was not till long afterwards that Rolfe and Burton discovered that they, too, had not come off unscathed. Luckily it was only Rolfe's sword-hilt that had been shattered, not his groin; while Burton examined with a wondering curiosity two neat black holes in the loose sleeve of his overalls.

It did not occur to either of them that there was at least plenty of time to slip away and hide before the Germans came up. Their instinct was to save the aeroplane--a hopeless proposition, one would have thought.

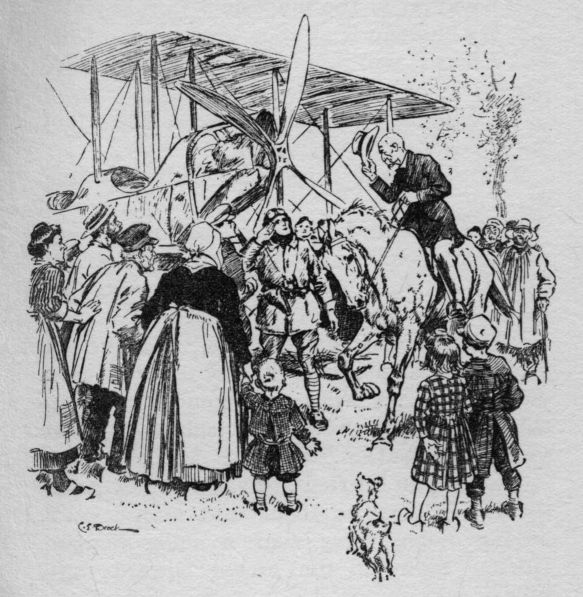

Along the road from the village, a quarter of a mile away, half the population was already speeding to the scene. The half, alas! was now the whole. There were women old and young, boys and girls, old men and men long past their prime; but there was no male person from seventeen to fifty except the village idiot, who flung his arms about as he ran, making inarticulate noises.

"Hang it all!" Burton ejaculated. "A crowd like this will dish any chance we might have had."

The crowd suddenly parted; the men doffed their hats, the women bobbed, as they made way for a horseman. It was an old straight figure, with short snow-white hair and a long grizzled moustache. He cantered through the throng, turned into the field on which the aeroplane lay, and reined up before the Englishmen.

"You have had an accident, messieurs?" he said, raising his hat.

"Worse than that, monsieur," replied Rolfe, in fluent French. "The Germans have hit us; the machine is useless; they are on our track."

"Ah!" exclaimed the Frenchman. Then, turning to the crowd who had flocked up behind him and stood gaping around, he spoke in quick, staccato phrases, in a tone of command. "Back to your houses, my good women. Take the children. These gentlemen are of our brave ally. You men, drag the aeroplane to the inn. Bid Froment lift the trap-door of his cellar ready to let the machine down. Some of you smooth away the tracks behind it. Quick! You, Guignet, post yourself on the mound yonder and watch for the Germans. The inn cellar is large, messieurs; there will be plenty of room. As to yourselves----"

The wrinkles of his aged face deepened.

"Ah, I have it!" he exclaimed. Turning to Rolfe, he went on: "You are an English officer, monsieur; that says itself. You have observations to report. Take my horse; it is not mine, but borrowed from one of my tenants; my own are with the army. There is no other in the village. It will serve you."

"Thank you, monsieur," said Rolfe, as the old man dismounted. "In the interests of our forces----"

"Hasten, monsieur," the old man interrupted. "Guignet waves his arms. He has seen the Germans. As for you, monsieur----"

"I will go to the inn," said Burton.

"My château is at your service, monsieur, but I fear it will prove an unsafe refuge. A haystack, or a barn----"

"I must stay by the aeroplane, monsieur; get it repaired if possible."

The old man shrugged. Guignet came up.

"The Bosches have taken the wrong road, monsieur le marquis," he said. "They are riding, ma foi! how quickly, towards old Lumineau's farm."

"That gives you more time," said the old gentleman to Burton. "Pray use it to save yourself. They will not be long discovering their mistake. Adieu! I salute in you your brave nation."

Bowing, he hurried away across the fields towards a large château that reared itself among noble trees half a mile distant. Burton followed the crowd towards the village inn.

"A fine old fellow!" he thought, "but he doesn't know the Germans if he supposes that the wine-cellar will be a safe place. I must find somewhere better than that."

He overtook the men before they reached the village. Passing the ancient church, an idea occurred to him.

"Is there a crypt?" he asked.

"Parfaitement, monsieur," a man replied.

"Halt a minute."

He hastened to the priest's house adjoining, at the door of which stood the curé in his biretta and long soutane. A minute's conversation settled the matter.

"It is a good cause, monsieur," said the curé. "Direct our friends."

Superintended by Burton, the men wheeled the machine through the great door into the church. While Burton rapidly unscrewed the planes, willing hands opened up the floor, and in a quarter of an hour the aeroplane was lowered into the crypt.

"Is there an engineer in the village?" Burton asked.

"Mais non, monsieur, but there is Boitelet, the smith--a clever fellow, monsieur. You should have seen him set monsieur le capitaine's automobile to rights. Boitelet is your man."

Burton hurried to the smithy. Boitelet, a shaggy giant of fifty years or so, accompanied him back to the church.

"Ah ça!" he exclaimed on examining the engine. "I can repair it, yes; but I must go for material to the town, ten miles away. It will be a full day's work, and what is monsieur to do, with the Bosches at hand?"

Burton thought quickly.

"Make me your assistant," he said after a minute or two. "I'll strip off my overalls and clothes; lend me things--a shirt and apron. A little more grease and dirt will disguise me."

"But monsieur is young," said the smith. "All our young men are at the war. The Bosches will make you prisoner--shoot you, perhaps."

"An awkward situation, truly," said Burton, rubbing a greasy hand over his face. Suddenly he remembered the half-witted stripling among the crowd. Could he feign idiocy as an explanation of his presence in the village? He could mop and mow, but nothing could banish the gleam of intelligence from his eyes. And his tongue!--he spoke French fairly well, but his accent would inevitably betray him to any German who chanced to be a linguist.

"There is only one thing," he cried. "I must pretend to be deaf and dumb. Tell everybody, will you?"

"It is clever, monsieur, that idea of yours," said the smith, laughing. "Yes; you are Jules le sourd-muet, burning to fight, but rejected because you could never hear the word of command. But you must be careful, monsieur; a single slip, and--voilà!"

He shrugged his shoulder expressively.

"The Bosches! The Bosches!" screamed a group of frightened children, rushing up the street.

The people fled into their houses and shut the doors. Only the curé and the smith were visible, the latter standing at his door leaning on his hammer, with an angry frown upon his swarthy face. Within the smithy Burton was making a rapid change of dress. He rolled up his own clothes and equipment and threw them into a corner behind a heap of old iron, and donned the dirty outer garments hurriedly provided by the smith. After a moment's hesitation he ferreted out his revolver case from the bundle, and slipped the revolver inside his blouse.

"If they search me, I'm done for," he thought. "But they would shoot the smith if they found the thing here, so it's as broad as it is long. The case must go up the chimney."

Then, completely transformed, he came to the door in time to see a troop of the Death's Head Hussars gallop up the street.

They reined up at the door of the smithy.

"Now, you dog, answer me," said the major in command. "And tell the truth, or I'll cut your tongue out. Have you seen an aeroplane hereabout?"

"Oui da, mon colonel," replied the smith, with an ironical courtesy that delighted Burton. "I did see an aeroplane, it might be an hour ago. It came down close to those poplars yonder, but rose in a minute or two and sailed away to the west."

"Go and see if he is telling the truth," said the officer to two of his men. "And you, smith, look to my horse's shoes. Who is this young fellow? A deserter? a coward?"

"Oh, he's brave enough, mon colonel," the smith answered. "But the poor wretch is deaf and dumb, a sore trouble to himself and his friends. You may shout, and he will not hear you; and as to asking for his dinner, he can't do it. I only employ him out of compassion."

The officer glanced at Burton, who was trying to assume that pathetically eager expression, that busy inquiry of the eyes, which characterises deaf mutes.

"If he were a German we'd make him shoot, deaf or not," said the major. "You French are too weak. Well?"

The troopers had returned, and sat their horses rigidly at the salute.

"Without doubt an aeroplane descended there, Herr Major," one of them reported, "and it flew up again, for there are no more tracks."

"It is not worth while continuing the chase. Night is coming on. Quarter yourselves in the village--and keep the people quiet. No one is to leave his house."

The troopers saluted and rode off, leaving a captain, two lieutenants, and four orderlies with the major.

"Look alive, smith," cried that officer, in the domineering tone evidently habitual with him. "Are the shoes in good order?"

The smith turned up the hoofs one after another, and pronounced them perfectly shod.

"Very well; if any of the troopers' horses need shoeing, see that it is done promptly, or it will be the worse for you. Now for the château, gentlemen; monsieur le marquis will be delighted to entertain us."

There was a look upon his face that Burton could not fathom--an ugly smile that made him shiver. The horsemen rode away, and Boitelet, the smith, spat upon the ground.

II

"Come inside, monsieur," murmured the smith, glancing round to see that no German was within hearing. Then he threw up his hands and groaned.

"He is an insolent hound," said Burton, sympathetically.

"Ah, monsieur, it is not that; all these Prussians are brutes. I fear for monsieur le marquis."

"Who is the marquis? He has a soldierly look."

"He was a fine soldier, monsieur. Every Frenchman knows his name. In the army he was plain General du Breuil; here in his own country, where we love him, we give him his true title, that has come to him from the days of long ago. Ah! there is great trouble for him. I know that man."

"The major?"

"Major he may be; spy he was. It is clear. Listen, monsieur. Some three years ago, before monsieur le marquis retired from the army, he had in his service a secretary, said to be an Alsatian, very useful to monsieur, who was compiling his memoirs. One day he was dismissed, none of us knew why. Monsieur le marquis had discovered something, no doubt. There was a violent scene at the château. Monsieur's son, Captain du Breuil, kicked the secretary down the steps. He came into the village, hired a calèche to drive him to the station, and departed. We have seen no more of him until this day. He is the major."

"You are sure?"

"It is certain, monsieur. He was then clean shaven, and now wears a moustache, but I know the scar on his cheek."

"And you fear he will insult the marquis?"

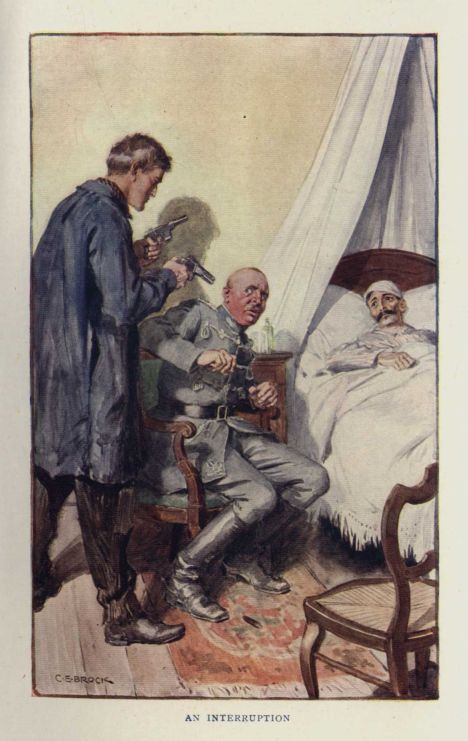

"Worse than that, monsieur. A few days ago monsieur le capitaine, brave soldier like his father, was wounded in action only a mile or two away, when our gallant cuirassiers charged the Bosches and drove them helter-skelter from their trenches. He was found on the field by old Guignet, and carried secretly to the château, and there he lies, horribly hurt by shrapnel."

"And now they will make him prisoner?"

"That would be bad enough, but I fear worse. The Bosches are brutal to all. What must we expect from a man who has a grudge to pay off, and finds his enemy helpless in his clutches? The major will not forgive his kicking."

"It's a bad look-out, certainly," said Burton. "I like your old general; he came to our help so quickly. But what about my engine?"

"Ah, oui, monsieur, it is a pity. I dare not leave the village now. The Bosches passed quickly through here in their retreat a few days ago; I did not expect to see their ugly faces again. You must wait, monsieur. Come into my house, and share our soup. If God pleases, the hounds will go again to-morrow."

Burton accepted the good man's offer of hospitality, and shared a simple meal with him, and his wife, and two wide-eyed children who gazed with interest at the stranger.

When the meal was nearly finished, the smith suddenly exclaimed--

"Ah! here comes old Pierre, with a German. Have a care, monsieur. Remember you are deaf and dumb."

Looking out of the window into the darkling street, Burton saw a bent old man tottering along by the side of one of the orderlies who had recently ridden away.

"They are not coming here, Dieu merci!" said the smith at his elbow. "They are going to the butcher's. These Germans eat like hogs."

"Who is the old man?" Burton asked.

"Servant of monsieur le marquis, monsieur. They have grown old together. There is no other left in the château. Some are at the war; the rest fled, maids and men, when the Germans came before. Ah! it is sad for monsieur and madame in their old age, and their son lying wounded, too."

The old serving-man passed from the butcher's to the baker's, and thence to other shops, with the orderly always at his side. Soon the old man was staggering under a load of purchases. He faltered and stopped, and the orderly shouted at him, and threatened him with his sword. Burton's blood boiled. He would have liked to catch the German by the neck and shake him until he howled for mercy.

Then an idea struck him. If he offered to help the laden old man he would make some return for the general's kindness; perhaps he might be of some further service in the château. He made the suggestion to the smith.

"It is madness, monsieur. You would put your head into the lion's mouth."

"What more natural than that a deaf mute should earn a sou by using his muscles? Arrange it, my friend."

"They say you English are mad, monsieur," said the smith with a shrug. "A la bonne heure! But you will get more kicks than sous."

"Make an opportunity to tell the old man that I am deaf and dumb, and that he is to pretend he knows me. He must inform his master and mistress also. Will he be discreet?"

"He will be anything you please for the sake of monsieur le marquis. Come, then, monsieur."

They left the house, and came upon the scene just as the orderly had terrorised the old man into making another attempt to carry his burden. The smith soon discovered that the orderly knew no French. He arranged the matter by signs, pointing to Burton's mouth and ears, and indicating that he was muscularly strong. At the same time he spoke rapidly in French to old Pierre.

"Ah, bon, bon!" said the old man. "I understand perfectly. Be sure I will tell the master. Monsieur may rely upon me."

Burton shouldered more than half the load, and set off for the château side by side with Pierre, the orderly following.

III

The Château du Breuil had been luckier than many similar country houses that stood in the line of the German advance. Whether by accident or a rare considerateness, it had not been shelled, and the officer who had last quartered himself there, though a German, was also a gentleman. It stood, a noble building, in its little park, whole and intact as the first marquis built it in the reign of Henri Quatre.

At either end was a projecting wing of two stories, the wings being connected by the long one-storied building that contained the living-rooms. Burton found the part of deaf mute irksome; he wished to question old Pierre as to the quarters in which the Germans had disposed themselves. But he perforce kept silence, listening to a fragmentary dialogue in German between the orderly and Pierre, who, as he afterwards learnt, had been valet to the marquis when the latter, as a young man, was military attaché to the French embassy at Berlin.

They arrived at the kitchen entrance. Pierre went in first, and at once addressed an old white-haired lady who was stuffing a chicken at the kitchen table. He spoke so rapidly and in so low a tone that Burton could not follow his words, but he gathered their purport when the old lady glanced at him, and signed to him to lay down his load on the table.

"Madame la marquise has understood," he thought.

The orderly waited awhile; then, seeing that the lady had set Pierre and the deaf mute to pare potatoes and turnips, he went off to report that preparations for dinner were at last in train.

"A thousand thanks, monsieur," whispered the marquise when the German's back was turned. "It was good of you to help old Pierre. But, believe me, it is unwise of you to stay. If you should be discovered---- If you made a slip----"

"Madame, to run risks is my daily work," said Burton. "I am glad to serve you--even in the capacity of kitchen-maid."

The marquise smiled wearily.

"We are playing strange parts, God help us!" she said. "I am in great distress, monsieur. The German officer----"

"Boitelet has told me about him, madame," said Burton. "Pardon: I interrupt; but we may have little time. Will you tell me what has happened?"

"My poor son! They dismissed our good doctor who was attending him; they carried him, ill as he is, from his own room to one of the servants' rooms, and there they have locked him in with my husband. It is on the floor above us. They have taken our rooms in the other wing for themselves. They have ransacked the wine-cellar, and loaded the table in the dining-room with my poor husband's finest vintage. But it is not what they have done but what they may do that fills me with dread. That horrible man----"

Old Pierre, who was standing near the door, at this moment put his finger quickly to his lips. When the orderly entered, the marquise was turning the chicken on the spit, and Burton was cleaning the knives.

"The old frau is slow," said the German to Pierre. "The officers are growing impatient. She had better hurry, or there will be trouble."

"Madame la marquise will serve the dinner when it is ready," said Pierre, quietly.

"Teufel! You are insolent," cried the orderly, striking the old man across the face.

Burton smothered the exclamation that rose to his lips. The marquise flashed at the German such a look of indignant scorn that he was abashed, and went out muttering sullenly.

"The visit of that horrible man," the old lady went on, ignoring the underling's brutality, "is not accidental, I am sure. He contemplates vengeance. He was dismissed with contumely, and I fear he will make my poor son pay."

Burton could only murmur his sympathy. He watched with admiration the quick, deft actions of the marquise, who prepared the dinner as skilfully as her own cook could have done.

There was no opportunity for further conversation. The orderly returned, and lolled in a chair, commenting on the old lady's movements in offensive tones that made Burton tingle. When the dishes were ready, the marquise told Pierre to carry them in.

"No, no, old witch," said the orderly, with a chuckle. "The Herr Major is very particular; she must serve him herself."

Pierre translated this to his mistress, protesting that she must not submit to such indignity.

"Eh bien, mon ami," she said, "they cannot hurt me more. For my son's sake I will be cook and bonne in one. Carry the dishes; I will show them how a marquise waits at table."

Burton assisted the old man to convey the dishes to the dining-room, following the marquise. At their entrance there was a shout of laughter. Four officers sat at the table--the major, his captain, and two moon-faced lieutenants.

"Where are your cap and apron, wench?" cried the major. "Go and put them on at once. And make that dumb dog there understand that he is not to bring his dirty face inside; he can hand the things to you through the hatch."

The marquise compressed her lips, and, without replying, returned to the kitchen, and came back in a maid's cap and apron. What was meant for indignity and insult seemed to Burton, watching from the hatch, to enhance the lady's dignity. She moved about the table with the quickness of a waiting maid and the proud bearing of a queen, paying no heed to the coarse pleasantries of the Germans, or to their complaints of the food, of which, nevertheless, they devoured large quantities.

"A tough fowl, this," said the major, "as old as the old hen herself."

"Ha, ha!" laughed his juniors, in whom the champagne they had already drunk induced a facile admiration of the major's wit.

As the meal progressed, and the Germans' potations deepened, their manners went from bad to worse. They commenced an orgy of plate-smashing, flinging pellets of damp bread at one another and at pictures on the walls. Burton's fingers tingled; from his place at the hatch he could have shot them one by one with the revolver that lay snug in his blouse. But he contained his anger. The four orderlies were in an adjacent room; the village was filled with the troopers; and hasty action would probably involve the destruction of the château and the massacre of its long-suffering inhabitants.