Cover

Cover

Cover

Cover

FORT PILLOW MASSACRE.

RETURNED PRISONERS.

SENATE.

IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War be, and they are hereby, instructed to inquire into the truth of the rumored slaughter of the Union troops, after their surrender, at the recent attack of the rebel forces upon Fort Pillow, Tennessee; as, also, whether Fort Pillow could have been sufficiently re-enforced or evacuated, and if so, why it was not done; and that they report the facts to Congress as soon as possible.

Approved April 21, 1864.

The Joint Committee on the Conduct and Expenditures of the War, to whom was referred the resolution of Congress instructing them to investigate the late massacre at Fort Pillow, designated two members of the committee—Messrs. Wade and Gooch—to proceed forthwith to such places as they might deem necessary, and take testimony. That sub-committee having discharged that duty, returned to this city, and submitted to the joint committee a report, with accompanying papers and testimony. The report was read and adopted by the committee, whose chairman was instructed to submit the same, with the testimony, to the Senate, and Mr. Gooch to the House, and ask that the same be printed.

Messrs. Wade and Gooch, the sub-committee appointed by the Joint Committee on the Conduct and Expenditures of the War, with instructions to proceed to such points as they might deem necessary for the purpose of taking testimony in regard to the massacre at Fort Pillow, submitted the following report to the joint committee, together with the accompanying testimony and papers:

In obedience to the instructions of this joint committee adopted on the 18th ultimo, your committee left Washington on the morning of the 19th, taking with them the stenographer of this committee, and proceeded to Cairo and Mound City, Illinois; Columbus, Kentucky; and Fort Pillow and Memphis, Tennessee; at each of which places they proceeded to take testimony.

Although your committee were instructed to inquire only in reference to the attack, capture, and massacre of Fort Pillow, they have deemed it proper to take some testimony in reference to the operations of Forrest and his command immediately preceding and subsequent to that horrible transaction. It will [Pg 2]appear, from the testimony thus taken, that the atrocities committed, at Fort Pillow were not the result of passions excited by the heat of conflict, but were the results of a policy deliberately decided upon and unhesitatingly announced. Even if the uncertainty of the fate of those officers and men belonging to colored regiments who have heretofore been taken prisoners by the rebels has failed to convince the authorities of our government of this fact, the testimony herewith submitted must convince even the most skeptical that it is the intention of the rebel authorities not to recognize the officers and men of our colored regiments as entitled to the treatment accorded by all civilized nations to prisoners of war. The declarations of Forrest and his officers, both before and after the capture of Fort Pillow, as testified to by such of our men as have escaped after being taken by him; the threats contained in the various demands for surrender made at Paducah, Columbus, and other places; the renewal of the massacre the morning after the capture of Fort Pillow; the statements made by the rebel officers to the officers of our gunboats who received the few survivors at Fort Pillow—all this proves most conclusively the policy they have determined to adopt.

The first operation of any importance was the attack upon Union city, Tennessee, by a portion of Forrest's command. The attack was made on the 24th of March. The post was occupied by a force of about 500 men under Colonel Hawkins, of the 7th Tennessee Union cavalry. The attacking force was superior in numbers, but was repulsed several times by our forces. For the particulars of the attack, and the circumstances attending the surrender, your committee would refer to the testimony herewith submitted. They would state, however, that it would appear from the testimony that the surrender was opposed by nearly if not quite all the officers of Colonel Hawkins's command. Your committee think that the circumstances connected with the surrender are such that they demand the most searching investigation by the military authorities, as, at the time of the surrender, but one man on our side had been injured.

On the 25th of March, the enemy, under the rebel Generals Forrest, Buford, Harris, and Thompson, estimated at over 6,000 men, made an attack on Paducah, Kentucky, which post was occupied by Colonel S. G. Hicks, 40th Illinois regiment, with 655 men. Our forces retired into Fort Anderson, and there made their stand—assisted by some gunboats belonging to the command of Captain Shirk of the navy—successfully repelling the attacks of the enemy. Failing to make any impression upon our forces, Forrest then demanded an unconditional surrender, closing his communication to Colonel Hicks in these words: "If you surrender you shall be treated as prisoners of war, but if I have to storm your works you may expect no quarter." This demand and threat was met by a refusal on the part of Colonel Hicks to surrender, he stating that he had been placed there by his government to defend that post, and he should do so. The rebels made three other assaults that same day, but were repulsed with heavy loss each time, the rebel General Thompson being killed in the last assault. The enemy retired the next day, having suffered a loss estimated at three hundred killed, and from 1,000 to 1,200 wounded. The loss on our side was 14 killed and 46 wounded.

The operations of the enemy at Paducah were characterized by the same bad faith and treachery that seem to have become the settled policy of Forrest and his command. The flag of truce was taken advantage of there, as elsewhere, to secure desirable positions which the rebels were unable to obtain by fair and honorable means; and also to afford opportunities for plundering private stores as well as government property. At Paducah the rebels were guilty of acts more cowardly, if possible, than any they have practiced elsewhere. When the attack was made the officers of the fort and of the gunboats advised the women and children to go down to the river for the purpose of being taken across out of danger. As they were leaving the town for that purpose, the rebel sharpshooters mingled with them, and, shielded by their presence, advanced and fired upon the gunboats, wounding some of our officers and men.[Pg 3] Our forces could not return the fire without endangering the lives of the women and children. The rebels also placed women in front of their lines as they moved on the fort, or were proceeding to take positions while the flag of truce was at the fort, in order to compel our men to withhold their fire, out of regard for the lives of the women who were made use of in this most cowardly manner. For more full details of the attack, and the treacherous and cowardly practices of the rebels there, your committee refer to the testimony herewith submitted.

On the 13th of April, the day after the capture of Fort Pillow, the rebel General Buford appeared before Columbus, Kentucky, and demanded its unconditional surrender. He coupled with that demand a threat that if the place was not surrendered, and he should be compelled to attack it, "no quarter whatever should be shown to the negro troops." To this Colonel Lawrence, in command of the post, replied, that "surrender was out of the question," as he had been placed there by his government to hold and defend the place, and should do so. No attack was made, but the enemy retired, having taken advantage of the flag of truce to seize some horses of Union citizens which had been brought in there for security.

It was at Fort Pillow, however, that the brutality and cruelty of the rebels were most fearfully exhibited. The garrison there, according to the last returns received at headquarters, amounted to 19 officers and 538 enlisted men, of whom 262 were colored troops, comprising one battalion of the 6th United States heavy artillery, (formerly called the 1st Alabama artillery,) of colored troops, under command of Major L. F. Booth; one section of the 2d United States light artillery, colored, and one battalion of the 13th Tennessee cavalry, white, commanded by Major W. F. Bradford. Major Booth was the ranking officer, and was in command of the post.

On Tuesday, the 12th of April, (the anniversary of the attack on Fort Sumter, in April, 1861,) the pickets of the garrison were driven in just before sunrise, that being the first intimation our forces there had of any intention on the part of the enemy to attack that place. Fighting soon became general, and about 9 o'clock Major Booth was killed. Major Bradford succeeded to the command, and withdrew all the forces within the fort. They had previously occupied some intrenchments at some distance from the fort, and further from the river.

This fort was situated on a high bluff, which descended precipitately to the river's edge, the side of the bluff on the river side being covered with trees, bushes, and fallen timber. Extending back from the river, on either side of the fort, was a ravine or hollow—the one below the fort containing several private stores and some dwellings, constituting what was called the town. At the mouth of that ravine, and on the river bank, were some government buildings containing commissary and quartermaster's stores. The ravine above the fort was known as Cold Creek ravine, the sides being covered with trees and bushes. To the right, or below and a little to the front of the fort, was a level piece of ground, not quite so elevated as the fort itself, on which had been erected some log huts or shanties, which were occupied by the white troops, and also used for hospital and other purposes. Within the fort tents had been erected, with board floors, for the use of the colored troops. There were six pieces of artillery in the fort, consisting of two 6-pounders, two 12-pounder howitzers, and two 10-pounder Parrotts.

The rebels continued their attack, but, up to two or three o'clock in the afternoon, they had not gained any decisive success. Our troops, both white and black, fought most bravely, and were in good spirits. The gunboat No. 7, (New Era,) Captain Marshall, took part in the conflict, shelling the enemy as opportunity offered. Signals had been agreed upon by which the officers in the fort could indicate where the guns of the boat could be most effective. There being but one gunboat there, no permanent impression appears to have been produced upon the enemy; for as they were shelled out of one ravine, they would make[Pg 4] their appearance in the other. They would thus appear and retire as the gunboat moved from one point to the other. About one o'clock the fire on both sides slackened somewhat, and the gunboat moved out in the river, to cool and clean its guns, having fired 282 rounds of shell, shrapnell, and canister, which nearly exhausted its supply of ammunition.

The rebels having thus far failed in their attack, now resorted to their customary use of flags of truce. The first flag of truce conveyed a demand from Forrest for the unconditional surrender of the fort. To this Major Bradford replied, asking to be allowed one hour to consult with his officers and the officers of the gunboat. In a short time a second flag of truce appeared, with a communication from Forrest, that he would allow Major Bradford twenty minutes in which to move his troops out of the fort, and if it was not done within that time an assault would be ordered. To this Major Bradford returned the reply that he would not surrender.

During the time these flags of truce were flying, the rebels were moving down the ravine and taking positions from which the more readily to charge upon the fort. Parties of them were also engaged in plundering the government buildings of commissary and quartermaster's stores, in full view of the gunboat. Captain Marshall states that he refrained from firing upon the rebels, although they were thus violating the flag of truce, for fear that, should they finally succeed in capturing the fort, they would justify any atrocities they might commit by saying that they were in retaliation for his firing while the flag of truce was flying. He says, however, that when he saw the rebels coming down the ravine above the fort, and taking positions there, he got under way and stood for the fort, determined to use what little ammunition he had left in shelling them out of the ravine; but he did not get up within effective range before the final assault was made.

Immediately after the second flag of truce retired, the rebels made a rush from the positions they had so treacherously gained and obtained possession of the fort, raising the cry of "No quarter!" But little opportunity was allowed for resistance. Our troops, black and white, threw down their arms, and sought to escape by running down the steep bluff near the fort, and secreting themselves behind trees and logs, in the bushes, and under the brush—some even jumping into the river, leaving only their heads above the water, as they crouched down under the bank.

Then followed a scene of cruelty and murder without a parallel in civilized warfare, which needed but the tomahawk and scalping-knife to exceed the worst atrocities ever committed by savages. The rebels commenced an indiscriminate slaughter, sparing neither age nor sex, white or black, soldier or civilian. The officers and men seemed to vie with each other in the devilish work; men, women, and even children, wherever found, were deliberately shot down, beaten, and hacked with sabres; some of the children not more than ten years old were forced to stand up and face their murderers while being shot; the sick and the wounded were butchered without mercy, the rebels even entering the hospital building and dragging them out to be shot, or killing them as they lay there unable to offer the least resistance. All over the hillside the work of murder was going on; numbers of our men were collected together in lines or groups and deliberately shot; some were shot while in the river, while others on the bank were shot and their bodies kicked into the water, many of them still living but unable to make any exertions to save themselves from drowning. Some of the rebels stood on the top of the hill or a short distance down its side, and called to our soldiers to come up to them, and as they approached, shot them down in cold blood; if their guns or pistols missed fire, forcing them to stand there until they were again prepared to fire. All around were heard cries of "No quarter!" "No quarter!" "Kill the damned niggers; shoot them down!" All who asked for mercy were answered by the[Pg 5] most cruel taunts and sneers. Some were spared for a time, only to be murdered under circumstances of greater cruelty. No cruelty which the most fiendish malignity could devise was omitted by these murderers. One white soldier who was wounded in one leg so as to be unable to walk, was made to stand up while his tormentors shot him; others who were wounded and unable to stand were held up and again shot. One negro who had been ordered by a rebel officer to hold his horse, was killed by him when he remounted; another, a mere child, whom an officer had taken up behind him on his horse, was seen by Chalmers, who at once ordered the officer to put him down and shoot him, which was done. The huts and tents in which many of the wounded had sought shelter were set on fire, both that night and the next morning, while the wounded were still in them—those only escaping who were able to get themselves out, or who could prevail on others less injured than themselves to help them out; and even some of those thus seeking to escape the flames were met by those ruffians and brutally shot down, or had their brains beaten out. One man was deliberately fastened down to the floor of a tent, face upwards, by means of nails driven through his clothing and into the boards under him, so that he could not possibly escape, and then the tent set on fire; another was nailed to the side of a building outside of the fort, and then the building set on fire and burned. The charred remains of five or six bodies were afterwards found, all but one so much disfigured and consumed by the flames that they could not be identified, and the identification of that one is not absolutely certain, although there can hardly be a doubt that it was the body of Lieutenant Akerstrom, quartermaster of the 13th Tennessee cavalry, and a native Tennesseean; several witnesses who saw the remains, and who were personally acquainted with him while living, have testified that it is their firm belief that it was his body that was thus treated.

These deeds of murder and cruelty ceased when night came on, only to be renewed the next morning, when the demons carefully sought among the dead lying about in all directions for any of the wounded yet alive, and those they found were deliberately shot. Scores of the dead and wounded were found there the day after the massacre by the men from some of our gunboats who were permitted to go on shore and collect the wounded and bury the dead. The rebels themselves had made a pretence of burying a great many of their victims, but they had merely thrown them, without the least regard to care or decency, into the trenches and ditches about the fort, or the little hollows and ravines on the hill-side, covering them but partially with earth. Portions of heads and faces, hands and feet, were found protruding through the earth in every direction. The testimony also establishes the fact that the rebels buried some of the living with the dead, a few of whom succeeded afterwards in digging themselves out, or were dug out by others, one of whom your committee found in Mound City hospital, and there examined. And even when your committee visited the spot, two weeks afterwards, although parties of men had been sent on shore from time to time to bury the bodies unburied and rebury the others, and were even then engaged in the same work, we found the evidences of this murder and cruelty still most painfully apparent; we saw bodies still unburied (at some distance from the fort) of some sick men who had been met fleeing from the hospital and beaten down and brutally murdered, and their bodies left where they had fallen. We could still see the faces, hands, and feet of men, white and black, protruding out of the ground, whose graves had not been reached by those engaged in re-interring the victims of the massacre; and although a great deal of rain had fallen within the preceding two weeks, the ground, more especially on the side and at the foot of the bluff where the most of the murders had been committed, was still discolored by the blood of our brave but unfortunate men, and the logs and trees showed but too plainly the evidences of the atrocities perpetrated there.

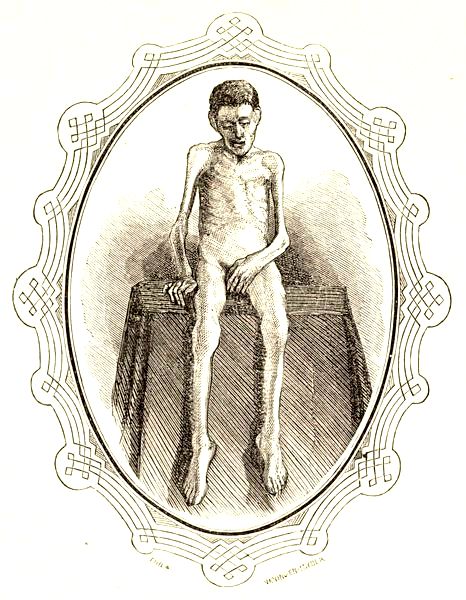

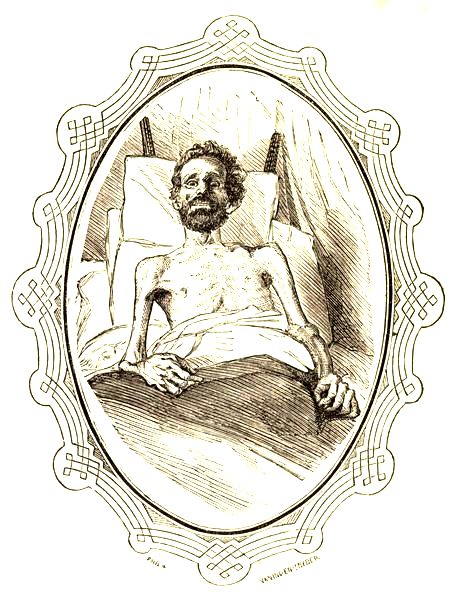

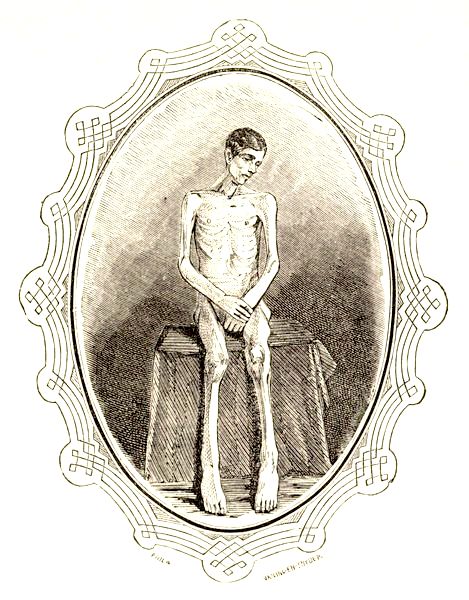

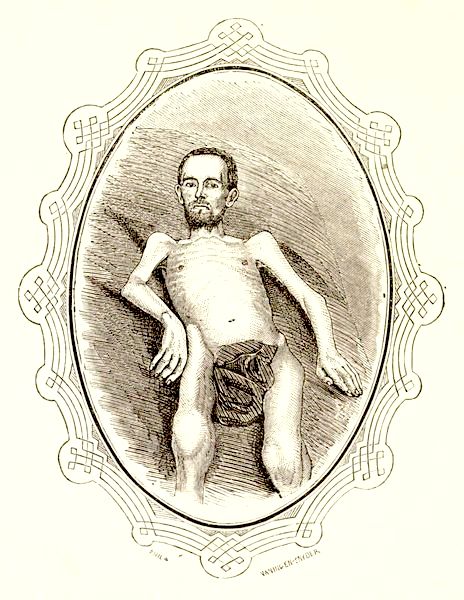

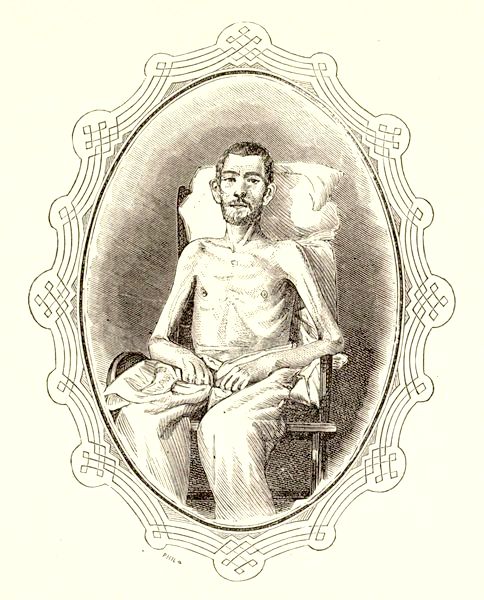

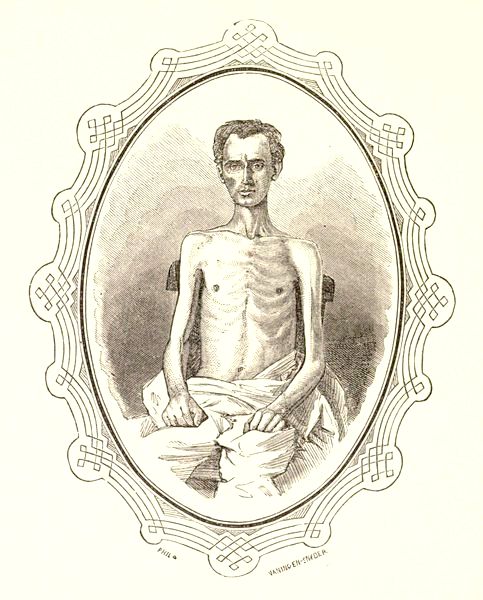

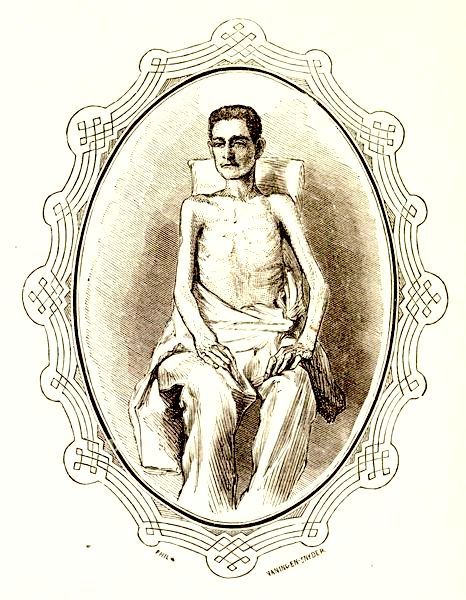

Many other instances of equally atrocious cruelty might be enumerated, but[Pg 6] your committee feel compelled to refrain from giving here more of the heart-sickening details, and refer to the statements contained in the voluminous testimony herewith submitted. Those statements were obtained by them from eye-witnesses and sufferers; many of them, as they were examined by your committee, were lying upon beds of pain and suffering, some so feeble that their lips could with difficulty frame the words by which they endeavored to convey some idea of the cruelties which had been inflicted on them, and which they had seen inflicted on others.

How many of our troops thus fell victims to the malignity and barbarity of Forrest and his followers cannot yet be definitely ascertained. Two officers belonging to the garrison were absent at the time of the capture and massacre. Of the remaining officers but two are known to be living, and they are wounded and now in the hospital at Mound City. One of them, Captain Potter, may even now be dead, as the surgeons, when your committee were there, expressed no hope of his recovery. Of the men, from 300 to 400 are known to have been killed at Fort Pillow, of whom, at least, 300 were murdered in cold blood after the post was in possession of the rebels, and our men had thrown down their arms and ceased to offer resistance. Of the survivors, except the wounded in the hospital at Mound City, and the few who succeeded in making their escape unhurt, nothing definite is known; and it is to be feared that many have been murdered after being taken away from the fort.

In reference to the fate of Major Bradford, who was in command of the fort when it was captured, and who had up to that time received no injury, there seems to be no doubt. The general understanding everywhere seemed to be that he had been brutally murdered the day after he was taken prisoner.

There is some discrepancy in the testimony, but your committee do not see how the one who professed to have been an eye-witness of his death could have been mistaken. There may be some uncertainty in regard to his fate.

When your committee arrived at Memphis, Tennessee, they found and examined a man (Mr. McLagan) who had been conscripted by some of Forrest's forces, but who, with other conscripts, had succeeded in making his escape. He testifies that while two companies of rebel troops, with Major Bradford and many other prisoners, were on their march from Brownsville to Jackson, Tennessee, Major Bradford was taken by five rebels—one an officer—led about fifty yards from the line of march, and deliberately murdered in view of all there assembled. He fell—killed instantly by three musket balls, even while asking that his life might be spared, as he had fought them manfully, and was deserving of a better fate. The motive for the murder of Major Bradford seems to have been the simple fact that, although a native of the south, he remained loyal to his government. The testimony herewith submitted contains many statements made by the rebels that they did not intend to treat "home-made Yankees," as they termed loyal southerners, any better than negro troops.

There is one circumstance connected with the events herein narrated which your committee cannot permit to pass unnoticed. The testimony herewith submitted discloses this most astounding and shameful fact: On the morning of the day succeeding the capture of Fort Pillow, the gunboat Silver Cloud, (No. 28,) the transport Platte Valley, and the gunboat New Era, (No. 7,) landed at Fort Pillow under flag of truce, for the purpose of receiving the few wounded there and burying the dead. While they were lying there, the rebel General Chalmers and other rebel officers came down to the landing, and some of them went on the boats. Notwithstanding the evidences of rebel atrocity and barbarity with which the ground was covered, there were some of our army officers on board the Platte Valley so lost to every feeling of decency, honor, and self-respect, as to make themselves disgracefully conspicuous in bestowing civilities and attention upon the rebel officers, even while they were boasting of the murders they had there committed. Your committee were unable to ascertain the names of[Pg 7] the officers who have thus inflicted so foul a stain upon the honor of our army. They are assured, however, by the military authorities that every effort will be made to ascertain their names and bring them to the punishment they so richly merit.

In relation to the re-enforcement or evacuation of Fort Pillow, it would appear from the testimony that the troops there stationed were withdrawn on the 25th of January last, in order to accompany the Meridian expedition under General Sherman. General Hurlbut testifies that he never received any instructions to permanently vacate the post, and deeming it important to occupy it, so that the rebels should not interrupt the navigation of the Mississippi by planting artillery there, he sent some troops there about the middle of February, increasing their number afterwards until the garrison amounted to nearly 600 men. He also states that as soon as he learned that the place was attacked, he immediately took measures to send up re-enforcements from Memphis, and they were actually embarking when he received information of the capture of the fort.

Your committee cannot close this report without expressing their obligations to the officers of the army and navy, with whom they were brought in contact, for the assistance they rendered. It is true your committee were furnished by the Secretary of War with the fullest authority to call upon any one in the army for such services as they might require, to enable them to make the investigation devolved upon them by Congress, but they found that no such authority was needed. The army and navy officers at every point they visited evinced a desire to aid the committee in every way in their power; and all expressed the highest satisfaction that Congress had so promptly taken steps to ascertain the facts connected with this fearful and bloody transaction, and the hope that the investigation would lead to prompt and decisive measures on the part of the government. Your committee would mention more particularly the names of General Mason Brayman, military commandant at Cairo; Captain J. H. Odlin, his chief of staff; Captain Alexander M. Pennock, United States navy, fleet captain of Mississippi squadron; Captain James W. Shirk, United States navy, commanding 7th district Mississippi squadron; Surgeon Horace Wardner, in charge of Mound City general hospital; Captain Thomas M. Farrell, United States navy, in command of gunboat Hastings, (furnished by Captain Pennock to convey the committee to Fort Pillow and Memphis;) Captain Thomas Pattison, naval commandant at Memphis; General C. C. Washburne, and the officers of their commands, as among those to whom they are indebted for assistance and attention.

All of which is respectfully submitted.

B. F. WADE.

D. W. GOOCH.

Adopted by the committee as their report.

B. F. WADE, Chairman.

CAIRO, ILLINOIS, April 22, 1864.

Brigadier General Mason Brayman sworn and examined by the chairman.

Question. What is your rank and position in the service?

Answer. Brigadier General of volunteers; have been in command of the district of Cairo since March 19, 1864.

Question. What was the extent of your district when you assumed command, and what your available force?

Answer. The river, from Paducah to Island No. Ten, inclusive, about 160 miles, and adjacent portions of Tennessee and Kentucky. My available force for duty, as appears from tri-monthly report of March 20, as follows:

| Paducah | officers and men | 408 |

| Cairo | do | 231 |

| Columbus | do | 998 |

| Hickman | do | 51 |

| Island No. Ten | do | 162 |

| Union City | do | 479 |

| Aggregate | 2,329 |

Question. What was the character of your force and the condition of your command at that time?

Answer. Three-fourths of the men were colored, a portion of them not mustered into service, and commanded by officers temporarily assigned, awaiting commission. Of the white troops about one-half at the posts on the river were on duty as provost marshals' guards and similar detached duties, leaving but a small number in condition for movement. The fortifications were in an unfinished condition, that at Cairo rendered almost useless by long neglect. Many of the guns were dismounted, or otherwise unfit for service, and the supply of ammunition deficient and defective. A body of cavalry at Paducah were not mounted, and only part of those at Union City. I had not enough mounted men within my reach for orderlies.

Question. What is the character of the public property and interests intrusted to your care?

Answer. Paducah commands the Ohio. In hostile hands, the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers are no longer ours. Mound City, eight miles above Cairo, is the great naval depot for the western fleet. Gunboats there receive their armaments, crews, and supplies. An average of probably $5,000,000 of public property is constantly at that point; I found it guarded by, perhaps, fifty men of the veteran reserve corps, not referring to gunboats lying there. Cairo, at the confluence of the great rivers, is the narrow gateway through which all military and naval operations of the Mississippi valley must be made. I cannot compute the amount or value of shipping and property at all times at this point. The committee must observe that the loss of Mound City and Cairo would paralyze the western army and navy. The points below Columbus and Island Ten are fortified places; while holding them, the rebels had control of the river. It required a prodigious effort to dislodge them. To concede to them any point on the river, even for a week, would bring disaster. Furthermore, the rebels now control western Kentucky; they are murdering, robbing, and driving out[Pg 9] the loyal men; they avow their determination to permit the loyal men to take no part in the approaching elections. Unless protected in their effort to protect themselves, the Union men must give way, and the country remain under insurrectionary control.

Question. Did you consider your force, as stated, adequate to the protection of your district?

Answer. Wholly inadequate, considering the interests at stake, and the hostile forces within attacking distance.

Question. When did you first hear that Forrest was advancing?

Answer. On March 23, four days after I took command, Colonel Hicks, at Paducah, and Colonel Hawkins at Union City, advised me by telegraph of the presence in their neighborhood of armed bands, both fearing an attack. At night of the same day, Colonel Hawkins reported Forrest at Jackson, 61 miles south, with 7,000 men; and again that he expected an attack within 24 hours. He wanted re-enforcements.

Question. Had you the means of re-enforcing him?

Answer. Of my own command, I had not 150 available men; however, some regiments and detachments of General Veatch's division had arrived and awaited the arrival of boats from St. Louis to carry them up the Tennessee. General Veatch had gone to Evansville, Indiana. Simultaneously with the reports from Hicks and Hawkins, I received from General Sherman, then at Nashville, this despatch: "Has General Veatch and command started up the Tennessee? If not, start them up at once." Down to this time it was uncertain whether Union City or Paducah was the real object of attack. Late in the evening I applied to Captain Fox, General Veatch's assistant adjutant general, to have 2,000 men in readiness to move during the night, if wanted, promising to have them back in time to embark, on arrival of their transports. I telegraphed Hawkins that he would receive aid, directing him to "fortify and keep well prepared." About 4-1/2 o'clock of the morning of the 24th, I was satisfied that Union City was the point of attack. Boats were impressed, four regiments were embarked, and I left at ten; disembarked at Columbus, and arriving within six miles of Union City at four p. m., where I learned that a surrender had taken place at 11 a. m., and the garrison marched off. I turned back, and at three the next morning turned over General Veatch's men, ready to go up the Tennessee.

Question. Why did you not pursue Forrest?

Answer. For three reasons: First, his force was all cavalry; mine all infantry. Second, he was moving on Paducah, and, while I could not overtake him by land, I could head him by the rivers. Third, another despatch from General Sherman reached me as I was going out from Columbus, prohibiting me from diverting the troops bound up the Tennessee from that movement on account of the presence of Forrest. My purpose was to save Union City, bring in its garrison, and have General Veatch's men back in time for their boats. While I was willing to risk much to secure a garrison supposed to be yet engaged in gallant defence, I could do nothing to mitigate the accomplished misfortune of a surrender.

Question. Do you think the surrender premature?

Answer. The garrison was within fortifications; the enemy had no artillery. A loss of one man killed and two or three wounded does not indicate a desperate case. The rebels were three times repulsed. A flag of truce followed, and a surrender.

Question. How large was the attacking party?

Answer. I judge fifteen hundred, the largest portion of Forrest's force being evidently on the way to Paducah.

Question. How large was his entire force?

Answer. Apparently 6,500.[Pg 10]

Question. When was Paducah attacked?

Answer. About 3 p. m. the next day, March 25.

Question. Was Paducah re-enforced previous to the attack?

Answer. It was not. I had no men to send, but sent supplies.

Question. Where was General Veatch's command?

Answer. Embarking for the Tennessee.

Question. Was Paducah well defended?

Answer. Most gallantly, and with success. The conduct of Colonel Hicks and his entire command was noble in the highest degree.

Question. How did his colored troops behave?

Answer. As well as the rest. Colonel Hicks thus refers to them in his official report: "I have been one of those men who never had much confidence in colored troops fighting, but those doubts are now all removed, for they fought as bravely as any troops in the fort."

Question. Why was the city shelled and set on fire?

Answer. Our small force retired within the fort; the rebels took possession of the town, and from adjacent buildings their sharpshooters fired upon us. It was necessary to dislodge them. The gunboats Peosta, Captain Smith, and Paw Paw, Captain O'Neal, and the fort drove them out, necessarily destroying property. Most of the inhabitants being still rebel sympathizers, there was less than the usual regret in performing the duty.

Question. What became of the enemy after the repulse?

Answer. They went south, and on the 26th I was notified by Colonel Hicks and by Colonel Lawrence that they were approaching Columbus.

Question. What was done?

Answer. I went to Columbus again, with such men as could be withdrawn from Cairo, and awaited an attack, but none was made. We were too strong, of which rebels in our midst had probably advised them.

Question. Do you permit rebels to remain within your lines?

Answer. Of course; after they have taken the oath.

Question. What is done in case they violate, by acting as spies, for instance?

Answer. I don't like to acknowledge that we swear them over again, but that is about what it amounts to.

Question. What became of your garrison at Hickman?

Answer. It was but 14 miles from Union City; too weak for defence, and unimportant. Having no re-enforcements to spare, I brought away the garrison.

Question. Was Union City important as a military post?

Answer. I think not, except to keep the peace and drive out guerillas. The railroad was operated to that point at the expense of the government, being used in carrying out supplies, which went mostly into disloyal hands, or were seized by Forrest. The road from Paducah to Mayfield was used by its owners. Enormous quantities of supplies needed by the rebel army were carried to Mayfield and other convenient points, and passed into the hands of the rebel army. I found this abuse so flagrant and dangerous that I made a stringent order stopping all trade. I furnish a copy herewith, making it part of my answer, (Exhibit A.)

Question. What, in your opinion, is the effect of free trade in western Kentucky and Tennessee?

Answer. Pernicious beyond measure; corrupting those in the public service, and furnishing needed supplies to enemies. I am in possession of intercepted correspondence, showing that while the trader who has taken the oath and does business at Paducah gets permits to send out supplies, several wagons at a time, his partner is receiving them within the rebel lines under permits issued by Forrest. A public officer is now under arrest and held for trial for covering up smuggling of contraband goods under permits, and sharing the profits. Pretended[Pg 11] loyal men and open enemies thus combined, and the rebel army gets the benefit. We are supplying our enemies with the means of resistance.

Question. Could not the rebels have been sooner driven out of your neighborhood?

Answer. They could by withdrawing men from duties which are presumed to be of greater importance. That point was settled by my superior officers. Forrest's force was near Mayfield, about equidistant from Paducah, Cairo, and Columbus, only a few hours from either. He was at the centre, I going round the edge of a circle. I could only watch the coming blow and help each weak point in turn. One evening, for instance, I sent 400 men to Columbus, expecting trouble there, and the next morning had them at Paducah, 75 miles distant.

Question. Had you instructions as to the presence of that force so near you?

Answer. Not specific. General Sherman, on the 23d of March, telegraphed that he was willing that Forrest should remain in that neighborhood if the people did not manifest friendship, and on April 13 he expressed a desire that Forrest should prolong his visit until certain measures could be accomplished. I think General Sherman did not purpose to withdraw a heavy force to pursue Forrest, having better use for them elsewhere, and feeling that we had force enough to hold the important points on the river. It may be that the strength of the enemy and the scattered condition of our small detachments was not fully understood. We ran too great a risk at Paducah. Nothing but great gallantry and fortitude saved it from the fate of Fort Pillow.

Question. What information had you of the attack of Fort Pillow?

Answer. Fort Pillow is 170 miles below here, not in my district, but Memphis. On April 13, at 6 p. m., I telegraphed General Sherman as follows:

"The surrender of Columbus was demanded and refused at six this morning. Women and children brought away. Heavy artillery firing this afternoon. I have sent re-enforcements. Paducah also threatened. No danger of either, but I think that Fort Pillow, in the Memphis district, is taken. General Shepley passed yesterday and saw the flag go down and thinks it a surrender. I have enough troops now from below, and will go down if necessary to that point. Captain Pennock will send gunboats. If lost, it will be retaken immediately."

I was informed, in reply, that Fort Pillow had no guns or garrison; had been evacuated; that General Hurlbut had force for its defence, &c. I understand that Fort Pillow had been evacuated and reoccupied, General Sherman not being aware of it. On the 14th he again instructed me as follows:

"What news from Columbus? Don't send men from Paris to Fort Pillow. Let General Hurlbut take care of that quarter. The Cairo troops may re-enforce temporarily at Paducah and Columbus, but should be held ready to come up the Tennessee. One object that Forrest has is to induce us to make these detachments and prevent our concentrating in this quarter."

Question. Did you have any conversation with General Shepley in relation to the condition of the garrison at Fort Pillow when he passed by that point? If so, state what he said. What force did General Shepley have with him? Did he assign any reason for not rendering assistance to that garrison? If so, what was it?

Answer. General Shepley called on me. He stated that as he approached Fort Pillow, fighting was going on; he saw the flag come down "by the run," but could not tell whether it was lowered by the garrison, or by having the halliards shot away; that soon after another flag went up in another place. He could not distinguish its character, but feared that it was a surrender, though firing continued. I think he gave the force on the boat as two batteries and two or three hundred infantry. When he came away the firing was kept up, but not as heavily as at first. He was not certain how the fight was terminating. In answer to a question of mine, he said the batteries on board could not have [Pg 12] been used, as the bluff was too steep for ascent or to admit of firing from the water's edge, and the enemy above might have captured them. This was about the substance of our conversation.

Question. What information have you relative to the battle and massacre at Fort Pillow, particularly what transpired after the surrender?

Answer. That place not being in my district, official reports did not come to me. However, under instructions from General Sherman, I detailed officers, and collected reports and sworn proofs for transmission to him, also to the Secretary of War. Having furnished the Secretary of War with a duplicate copy for the use of your committee if he so desired, I refer to that for the information I have on the subject.

Question. Do you consider the testimony thus furnished entirely reliable?

Answer. "In the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every work be established." Here are scores of them living and dying. There are doubtless errors as to time and place, and scenes witnessed from different points of observation, but in the main I regard the witnesses honest and their accounts true.

Question. What did you learn concerning violations of the flag of truce?

Answer. I learn from official sources that at Paducah, Columbus, Union City, and Fort Pillow, the rebels moved troops, placed batteries, formed new lines, advanced, robbed stores and private houses, stole horses and other property while protected by flags of truce. J. W. McCord and Mrs. Hannah Hammond state, in writing, that at Paducah they forced five women nurses at the hospital out in front of their line, and kept them there for an hour, thus silencing our guns. Mrs. Hammond was one of the five. Reference is made to testimony furnished on the subject, and to official reports when transmitted to the War Department.

Question. What information have you as to the intention of the enemy to perpetrate such acts as the massacre at Fort Pillow?

Answer. I furnish the correspondence growing out of demands to surrender at Union City, Paducah, and Columbus, showing premeditation on the part of officers in command of the rebel army.

[Take in from reports of Lieutenant Gray, Colonel Hicks and Colonel Lawrence, with which the committee is furnished.—See Appendix.]

Question. Has there been co-operation and harmony among commanders since these troubles began?

Answer. Entire and in every respect, so far as I know. Officers of the army in charge of troops temporarily here gave all the aid possible. They were under orders which prevented their going out in pursuit of Forrest, but they gave me detachments to guard our river posts when threatened.

Question. What have been the relations existing generally between you and Captain Pennock, of the navy, fleet captain of the Mississippi squadron?

Answer. Captain Pennock is commandant of the naval station at Cairo and Mound City, and I understand represents Admiral Porter in his absence. Our relations have been cordial, and we have co-operated in all movements. The aid given by his gunboats has been prompt, ample, and very efficient. His admirable judgment and ready resources have always been available.

Question. During the operations consequent upon the movements of Forrest, did you or did you not receive cordial co-operation and support from Lieutenant Commander Shirk, commanding the 7th division Mississippi squadron?

Answer. I can only repeat my answer to the last question. Lieutenant Shirk is an admirable officer, vigilant, brave, and of exceedingly safe judgment.[Pg 13]

Mound City, Illinois, April 22, 1864.

Surgeon Horace Wardner sworn and examined.

By the chairman:

Question. Have you been in charge of this hospital, Mound City hospital?

Answer. I have been in charge of this hospital continually since the 25th of April, 1863.

Question. Will you state, if you please, what you know about the persons who escaped from Fort Pillow? And how many have been under your charge?

Answer. I have received thirty-four whites, twenty-seven colored men, and one colored woman, and seven corpses of those who died on their way here.

Question. Did any of those you have mentioned escape from Fort Pillow?

Answer. There were eight or nine men, I forget the number, who did escape and come here, the others were paroled. I learned the following facts about that: The day after the battle a gunboat was coming up and commenced shelling the place; the rebels sent a flag of truce for the purpose of giving over into our hands what wounded remained alive; a transport then landed and sent out details to look about the grounds and pick up the wounded there, and bring them on the boat. They had no previous attention.

Question. They were then brought under your charge?

Answer. They were brought immediately to this hospital.

Question. Who commanded that boat?

Answer. I forget the naval officer's name.

Question. How long after the capture of the place did he come along?

Answer. That was the next day after the capture.

Question. Did all who were paroled in this way come under your charge, or did any of them go to other hospitals?

Answer. None went to other hospitals that I am aware of.

Question. Please state their condition.

Answer. They were the worst butchered men I have ever seen. I have been in several hard battles, but I have never seen men so mangled as they were; and nearly all of them concur in stating that they received all their wounds after they had thrown down their arms, surrendered, and asked for quarters. They state that they ran out of the fort, threw down their arms, and ran down the bank to the edge of the river, and were pursued to the top of the bank and fired on from above.

Question. Were there any females there?

Answer. I have one wounded woman from there.

Question. Were there any children or young persons there?

Answer. I have no wounded children or young persons from there.

Question. Those you have received were mostly combatants, or had been?

Answer. Yes, sir, soldiers, white or colored.

Question. Were any of the wounded here in the hospital in the fort, and wounded while in the hospital?

Answer. I so understand them.

Question. How many in that condition did you understand?

Answer. I learned from those who came here that nearly all who were in the hospital were killed. I received a young negro boy, probably sixteen years old, who was in the hospital there sick with fever, and unable to get away. The rebels entered the hospital, and with a sabre hacked his head, no doubt with the intention of splitting it open. The boy put up his hand to protect his head, and they cut off one or two of his fingers. He was brought here insensible, and died yesterday. I made a post-mortem examination, and found that the outer table of the skull was incised, the inner table was fractured, and a piece driven into the brain.

Question. This was done while he was sick in the hospital?

Answer. Yes, sir, unable to get off his bed.[Pg 14]

Question. Have you any means of knowing how many were murdered in that way?

Answer. No positive means, except the statement of the men.

Question. How many do you suppose from the information you have received?

Answer. I suppose there were about four hundred massacred—murdered there.

Question. What proportion white, and what proportion colored, as near as you could ascertain?

Answer. The impression I have, from what I can learn, is, that all the negroes were massacred except about eighty, and all the white soldiers were killed except about one hundred or one hundred and ten.

Question. We have heard rumors that some of these persons were buried alive; did you hear anything about that?

Answer. I have two in the hospital here who were buried alive.

Question. Both colored men?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. How did they escape?

Answer. One of them I have not conversed with personally, the other I have. He was thrown into a pit, as he states, with a great many others, white and black, several of whom were alive; they were all buried up together. He lay on the outer edge, but his head was nearer the surface; he had one well hand, and with that hand he was able to work a place through which he could breathe, and in that way he got his head out; he lay there for some twenty-four hours, and was finally taken out by somebody. The others, next to him, were buried so deep that they could not get out, and died.

Question. Did you hear anything about any of them having been thrown into the flames and burned?

Answer. I do not know anything about that myself. These men did not say much, and in fact I did not myself have time to question them very closely.

Question. What is the general condition now of the wounded men from Fort Pillow under your charge?

Answer. They are in as good condition as they can be, probably about one-third of them must die.

Question. Is your hospital divided into wards, and can we go through and take the testimony of these men, ward by ward?

Answer. It is divided into wards. The men from Fort Pillow are scattered

through the hospital, and isolated to prevent erysipelas. If I should crowd too

many badly wounded men in one ward I would be likely to get the erysipelas

among them, and lose a great many of them.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Are the wounds of these men such as men usually receive in battle?

Answer. The gunshot wounds are; the sabre cuts are the first I have ever seen in the war yet. They seem to have been shot with the intention of hitting the body. There are more body wounds than in an ordinary battle.

Question. Just as if they were close enough to select the parts of the body to be hit?

Answer. Yes, sir; some of them were shot with pistols by the rebels standing from one foot to ten feet of them.

The committee then proceeded to the various wards and took the testimony

of such of the wounded as were able to bear the examination.

The testimony of the colored men is written out exactly as given, except that it is rendered in a grammatical form, instead of the broken language some of them used.[Pg 15]

Elias Falls, (colored,) private, company A, 6th United States heavy artillery,

or 1st Alabama artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Were you at Fort Pillow when the battle took place there, and it was captured by the rebels?

Answer. I was there; I was a cook, and was waiting on the captain and major.

Question. What did you see done there? What did the rebels do after they came into the fort?

Answer. They killed all the men after they surrendered, until orders were given to stop; they killed all they came to, white and black, after they had surrendered.

Question. The one the same as the other?

Answer. Yes, sir, till he gave orders to stop firing.

Question. Till who gave orders?

Answer. They told me his name was Forrest.

Question. Did you see anybody killed or shot there?

Answer. Yes, sir; I was shot after the surrender, as I was marched up the hill by the rebels.

Question. Where were you wounded?

Answer. In the knee.

Question. Was that the day of the fight?

Answer. The same day.

Question. Did you see any men shot the next day?

Answer. I did not.

Question. What did you see done after the place was taken?

Answer. After peace was made some of the secesh soldiers came around cursing the boys that were wounded. They shot one of them about the hand, aimed to shoot him in the head, as he lay on the ground, and hit him in the hand; and an officer told the secesh soldier if he did that again he would arrest him, and he went off then.

Question. Did they burn any buildings?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Was anybody burned in the buildings?

Answer. I did not see anybody burned; I saw them burn the buildings; I was not able to walk about; I staid in a building that night with some three or four white men.

Question. Do you know anything about their going into the hospital and killing those who were there sick in bed?

Answer. We had some three or four of our men there, and some of our men came in and said they had killed two women and two children.

Duncan Harding, (colored,) private, company A, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Were you in Fort Pillow at the time it was captured?

Answer. Yes, sir; I was a gunner No. 2 at the gun.

Question. What did you see there?

Answer. I did not see much until next morning. I was shot in the arm that evening; they picked me up and marched me up the hill, and while they were marching me up the hill they shot me again through the thigh.[Pg 16]

Question. Did you see anybody else shot after they had surrendered?

Answer. The next morning I saw them shoot down one corporal in our company.

Question. What was his name?

Answer. Robert Winston.

Question. Did they kill him?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. What were you doing at the time?

Answer. I was lying down.

Question. What was the corporal doing?

Answer. When the gunboats commenced firing he was started off with them, but he would not go fast enough and they shot him dead.

Question. When you were shot the last time had you any arms in your hands?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Had the corporal any arms in his hands?

Answer. No, sir; nothing.

By the chairman:

Question. What do you know about any buildings being burned?

Answer. I saw them burn the buildings; and that morning as I was going to the boat I saw one colored man who was burned in the building.

Question. When was that building burned?

Answer. The next morning.

Question. The morning after the capture?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. How did you get away?

Answer. I started off with the rebels; we were all lying in a hollow to keep from the shells; as their backs were turned to me I crawled up in some brush and logs, and they all left; when night come I came back to the river bank, and a gunboat came along.

Question. Were any officers about when you were shot last?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Did you know any of them?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Did they say anything against it?

Answer. No, sir; only, "Kill the God damned nigger."

Nathan Hunter, (colored,) private, company D, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Were you in Fort Pillow when it was captured?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. What did you see done there?

Answer. They went down the hill, and shot all of us they saw; they shot me for dead, and I lay there until the next morning when the gunboat came along. They thought I was dead and pulled my boots off. That is all I know.

Question. Were you shot when they first took the fort?

Answer. I was not shot until we were done fighting.

Question. Had you any arms in your hands when you were shot?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. How long did you lie where you were shot?

Answer. I lay there from three o'clock until after night, and then I went up in the guard-house and staid there until the next morning when the gunboat came along.

Question. Did you see any others shot?

Answer. Yes, sir; they shot down a whole parcel along with me. Their[Pg 17] bodies were lying there along the river bank the next morning. They kicked some of them into the river after they were shot dead.

Question. Did you see that?

Answer. Yes, sir; I thought they were going to throw me in too; I slipped away in the night.

By the chairman:

Question. Did you see any man burned?

Answer. No, sir; I was down under the hill next the river.

Question. They thought you were dead when they pulled your boots off?

Answer. Yes, sir; they pulled my boots off, and rolled me over, and said they had killed me.

Sergeant Benjamin Robinson, (colored,) company D, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Were you at Fort Pillow in the fight there?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. What did you see there?

Answer. I saw them shoot two white men right by the side of me after they had laid their guns down. They shot a black man clear over into the river. Then they hallooed to me to come up the hill, and I came up. They said, "Give me your money, you damned nigger." I told them I did not have any. "Give me your money, or I will blow your brains out." Then they told me to lie down, and I laid down, and they stripped everything off me.

Question. This was the day of the fight?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Go on. Did they shoot you?

Answer. Yes, sir. After they stripped me and took my money away from me they dragged me up the hill a little piece, and laid me down flat on my stomach; I laid there till night, and they took me down to an old house, and said they would kill me the next morning. I got up and commenced crawling down the hill; I could not walk.

Question. When were you shot?

Answer. About 3 o'clock.

Question. Before they stripped you?

Answer. Yes, sir. They shot me before they said, "come up."

Question. After you had surrendered?

Answer. Yes, sir; they shot pretty nearly all of them after they surrendered.

Question. Did you see anything of the burning of the men?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Did you see them bury anybody?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Did they bury anybody who was not dead?

Answer. I saw one of them working his hand after he was buried; he was a black man. They had about a hundred in there, black and white. The major was buried on the bank, right side of me. They took his clothes all off but his drawers; I was lying right there looking at them. They had my captain's coat, too; they did not kill my captain; a lieutenant told him to give him his coat, and then they told him to go down and pick up those old rags and put them on.

Question. Did you see anybody shot the day after the battle?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. How did you get away?

Answer. A few men came up from Memphis, and got a piece of plank and put me on it, and took me down to the boat.[Pg 18]

Question. Were any rebel officers around when the rebels were killing our men?

Answer. Yes, sir; lots of them.

Question. Did they try to keep their men from killing our men?

Answer. I never heard them say so. I know General Forrest rode his horse over me three or four times. I did not know him until I heard his men call his name. He said to some negro men there that he knew them; that they had been in his nigger yard in Memphis. He said he was not worth five dollars when he started, and had got rich trading in negroes.

Question. Where were you from?

Answer. I came from South Carolina.

Question. Have you been a slave?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Daniel Tyler, (colored,) private, company B, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Where were you raised?

Answer. In Mississippi.

Question. Have you been a slave?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Were you in Fort Pillow at the time it was captured by the rebels?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. When were you wounded?

Answer. I was wounded after we all surrendered; not before.

Question. At what time?

Answer. They shot me when we came up the hill from down by the river.

Question. Why did you go up the hill?

Answer. They called me up.

Question. Did you see who shot you?

Answer. Yes, sir; I did not know him.

Question. One of the rebels?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. How near was he to you?

Answer. I was right at him; I had my hand on the end of his gun.

Question. What did he say to you?

Answer. He said, "Whose gun are you holding?" I said, "Nobody's." He said, "God damn you, I will shoot you," and then he shot me. I let go, and then another one shot me.

Question. Were many shot at the same time?

Answer. Yes, sir, lots of them; lying all round like hogs.

Question. Did you see any one burned?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Did you see anybody buried alive?

Answer. Nobody but me.

Question. Were you buried alive?

Answer. Yes, sir; they thought they had killed me. I lay there till about sundown, when they threw us in a hollow, and commenced throwing dirt on us.

Question. Did you say anything?

Answer. No, sir; I did not want to speak to them. I knew if I said anything they would kill me. They covered me up in a hole; they covered me up, all but one side of my head. I heard them say they ought not to bury a man who was alive. I commenced working the dirt away, and one of the secesh made a young one dig me out. They dug me out, and I was carried not far off to a fire.[Pg 19]

Question. How long did you stay there?

Answer. I staid there that night and until the next morning, and then I slipped off. I heard them say the niggers had to go away from there before the gunboat came, and that they would kill the niggers. The gunboat commenced shelling up there, and they commenced moving off. I heard them up there shooting. They wanted me to go with them, but I would not go. I turned around, and came down to the river bank and got on the gunboat.

Question. How did you lose your eye?

Answer. They knocked me down with a carbine, and then they jabbed it out.

Question. Was that before you were shot?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. After you had surrendered?

Answer. Yes, sir; I was going up the hill, a man came down and met me; he had his gun in his hand, and whirled it around and knocked me down, and then took the end of his carbine and jabbed it in my eye, and shot me.

Question. Were any of their officers about there then?

Answer. I did not see any officers.

Question. Were any white men buried with you?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Were any buried alive?

Answer. I heard that one white man was buried alive; I did not see him.

Question. Who said that?

Answer. A young man; he said they ought not to have done it. He staid in there all night; I do not know as he ever got out.

John Haskins, (colored,) private, company B, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Were you at Fort Pillow when it was captured?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. What did you see done there?

Answer. After we had surrendered they shot me in the left arm. I ran down the river and jumped into the water; the water ran over my back; six or seven more men came around there, and the secesh shot them right on the bank. At night I got in a coal-boat and cut it loose, and went down the river.

Question. Did you see anybody else killed after they had surrendered?

Answer. A great many; I could not tell how many.

Question. Did they say why they killed our men after they had surrendered?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. How many did you see killed after they surrendered?

Answer. Six or eight right around me, who could not get into the water as I did; I heard them shooting above, too.

Question. Did they strip and rob those they killed?

Answer. Yes, sir; they ran their hands in my pockets—they thought I was dead—they did all in the same way.

Question. What time were you shot?

Answer. After four o'clock.

Question. How long after you had surrendered?

Answer. Just about the time we ran down the hill.

Question. Did you have any arms in your hands when you were shot?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Do you know anything about their killing anybody in the hospital?

Answer. I could not tell anything about that.

Question. Do you know anything about their burning buildings?[Pg 20]

Answer. Yes, sir; they burned the lieutenant's house, and they said they burned him in the house.

Question. He was a white man?

Answer. Yes, sir; quartermaster of the 13th Tennessee cavalry.

Question. Did you see them kill him?

Answer. No, sir; I did not see them kill him; I saw the house he was in on fire.

Question. Do you know anything about their burying anybody before they were dead?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Where are you from?

Answer. From Tennessee.

Question. Have you been a slave?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. How long have you been in the army?

Answer. About two months.

Thomas Adison, (colored,) private, company C, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By the chairman:

Question. Where were you raised?

Answer. In South Carolina. I was nineteen years old when I came to Mississippi. I was forty years old last March.

Question. Were you at Fort Pillow when it was captured?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. When were you wounded—before or after you surrendered?

Answer. Before.

Question. What happened to you after you were wounded?

Answer. I went down the hill after we surrendered; then they came down and shot me again in my face, breaking my jaw-bone.

Question. How near was the man to you?

Answer. He shot me with a revolver, about ten or fifteen feet off.

Question. What happened to you then?

Answer. I laid down, and a fellow came along and turned me over and searched my pockets and took my money. He said: "God damn his old soul; he is sure dead now; he is a big, old, fat fellow."

Question. How long did you lay there?

Answer. About two hours.

Question. Then what was done with you?

Answer. They made some of our men carry me up the hill to a house that was full of white men. They made us lie out doors all night, and said that the next morning they would have the doctor fix us up. I went down to a branch for some water, and a man said to me: "Old man, if you stay here they will kill you, but if you get into the water till the boat comes along they may save you;" and I went off. They shot a great many that evening.

Question. The day of the fight?

Answer. Yes, sir. I heard them shoot little children not more than that high, [holding his hand off about four feet from the floor,] that the officers had to wait upon them.

Question. Did you see them shoot them?

Answer. I did not hold up my head.

Question. How did you know that they shot them then?

Answer. I heard them say, "Turn around so that I can shoot you good;" and then I heard them fire, and then I heard the children fall over.

Question. Do you know that those were the boys that waited upon the officers?[Pg 21]

Answer. Yes, sir; one was named Dave, and the other was named Anderson.

Question. Did you see them after they were shot?

Answer. No, sir; they toted them up the hill before me, because they were small. I never saw folks shot down so in my life.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Do you know of anybody being buried alive?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Do you know of any one being burned?

Answer. They had a whole parcel of them in a house, and I think they burned them. The house was burned up, and I think they burned them in it.

Question. Were the men in the house colored men?

Answer. No, sir. The rebels never would have got the advantage of us if it had not been for the houses built there, and which made better breastworks for them than we had. The major would not let us burn the houses in the morning. If they had let us burn the houses in the morning, I do not believe they would ever have whipped us out of that place.

Manuel Nichols, (colored,) private, Company B, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Were you in the late fight at Fort Pillow?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Were you wounded there?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. When?

Answer. I was wounded once about a half an hour before we gave up.

Question. Did they do anything to you after you surrendered?

Answer. Yes, sir; they shot me in the head under my left ear, and the morning after the fight they shot me again in the right arm. When they came up and killed the wounded ones, I saw some four or five coming down the hill. I said to one of our boys, "Anderson, I expect if those fellows come here they will kill us." I was lying on my right side, leaning on my elbow. One of the black soldiers went into the house where the white soldiers were. I asked him if there was any water in there, and he said yes; I wanted some, and took a stick and tried to get to the house. I did not get to the house. Some of them came along, and saw a little boy belonging to company D. One of them had his musket on his shoulder, and shot the boy down. He said: "All you damned niggers come out of the house; I am going to shoot you." Some of the white soldiers said, "Boys, it is only death anyhow; if you don't go out they will come in and carry you out." My strength seemed to come to me as if I had never been shot, and I jumped up and ran down the hill. I met one of them coming up the hill; he said "stop!" but I kept on running. As I jumped over the hill, he shot me through the right arm.

Question. How many did you see them kill after they had surrendered?

Answer. After I surrendered I did not go down the hill. A man shot me under the ear, and I fell down and said to myself, "If he don't shoot me any more this won't hurt me." One of their officers came along and hallooed, "Forrest says, no quarter! no quarter!" and the next one hallooed, "Black flag! black flag!"

Question. What did they do then?

Answer. They kept on shouting. I could hear them down the hill.

Question. Did you see them bury anybody?

Answer. Yes, sir; they carried me around right to the corner of the fort, and I saw them pitch men in there.

Question. Was there any alive?[Pg 22]

Answer. I did not see them bury anybody alive.

Question. How near to you was the man who shot you under the ear?

Answer. Right close to my head. When I was shot in the side, a man turned me over, and took my pocket-knife and pocket-book. I had some of these brass things that looked like cents. They said, "Here's some money; here's some money." I said to myself, "You got fooled that time."

Arthur Edwards, (colored,) private, company C, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By the chairman:

Question. Where were you raised?

Answer. In Mississippi.

Question. Were you in Fort Pillow when it was taken?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Tell what you saw there.

Answer. I was shot after I surrendered.

Question. When?

Answer. About half past four o'clock.

Question. Where were you when you were shot?

Answer. I was lying down behind a log.

Question. Where were you shot?

Answer. In the head first, then in the shoulder, then in my right wrist; and then in the head again, about half an hour after that.

Question. How many men shot at you?

Answer. One shot at me three times, and then a lieutenant shot at me.

Question. Did they say anything when they shot you?

Answer. No, sir, only I asked them not to shoot me, and they said, "God damn you, you are fighting against your master."

Question. How near was the man to you when he shot you?

Answer. He squatted down, and held his pistol close to my head.

Question. How near was the officer to you when he shot you?

Answer. About five or ten feet off; he was sitting on his horse.

Question. Who said you were fighting against your master?

Answer. The man that shot me.

Question. What did the officer say?

Answer. Nothing, but "you God damned nigger." A captain told him not to do it, but he did not mind him; he shot me, and run off on his horse.

Question. Did you see the captain?

Answer. Yes, sir; he and the captain were side by side.

Question. Did you know the captain?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. How long did you stay there?

Answer. Until next morning about 9 o'clock.

Question. How did you get away?

Answer. When the gunboat commenced shelling I went down the hill, and staid there until they carried down a flag of truce. Then the gunboat came to the bank, and a secesh lieutenant made us go down to such a place, and told us to go no further, or we would get shot again. Then the gunboat men came along to bury the dead, and told us to go on the boat.

Question. Did you see anybody shot after they had surrendered, besides yourself?

Answer. Yes, sir; they shot one right by me, and lots of the 13th Tennessee cavalry.

Question. After they had surrendered?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Do you know whether any were buried alive?[Pg 23]

Answer. Not that I saw.

Question. Did you see anybody buried?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. Did you see anybody shot the day after the fight?

Answer. No, sir.

Charles Key, (colored,) private, company D, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Where were you raised?

Answer. In South Carolina.

Question. Have you been a slave?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Where did you enlist?

Answer. In Tennessee.

Question. Were you in the fight at Fort Pillow?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. What did you see done there after the fight was over?

Answer. I saw nothing, only the boys run down the hill, and they came down and shot them.

Question. Were you wounded before or after you surrendered?

Answer. After the surrender, about 5 o'clock.

Question. Did you have your gun in your hands when you were wounded?

Answer. No, sir; I threw my gun into the river.

Question. How did they come to shoot you?

Answer. I was in the water, and a man came down and shot me with a revolver.

Question. Did you see anybody else shot?

Answer. Yes, sir; right smart of them, in an old coal boat. I saw one man start up the bank after he was shot in the arm, and then a fellow knocked him back into the river with his carbine, and then shot him. I did not go up the hill after I was shot. I laid in the water like I was dead until night, and then I made up a fire and dried myself, and staid there till the gunboat came along.

Question. Did they shoot you more than once?

Answer. No, sir.

Henry Christian, (colored,) private, company B, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

Question. Where were you raised?

Answer. In East Tennessee.

Question. Have you been a slave?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Where did you enlist?

Answer. At Corinth, Mississippi.

Question. Were you in the fight at Fort Pillow?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. When were you wounded?

Answer. A little before we surrendered.

Question. What happened to you afterwards?

Answer. Nothing; I got but one shot, and dug right out over the hill to the river, and never was bothered any more.

Question. Did you see any men shot after the place was taken?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Where?[Pg 24]

Answer. Down to the river.

Question. How many?

Answer. A good many; I don't know how many.

Question. By whom were they shot?

Answer. By secesh soldiers; secesh officers shot some up on the hill.

Question. Did you see those on the hill shot by the officers?

Answer. I saw two of them shot.

Question. What officers were they?

Answer. I don't know whether he was a lieutenant or captain.

Question. Did the men who were shot after they had surrendered have arms in their hands?

Answer. No, sir; they threw down their arms.

Question. Did you see any shot the next morning?

Answer. I saw two shot; one was shot by an officer—he was standing, holding the officer's horse, and when the officer came and got his horse he shot him dead. The officer was setting fire to the houses.

Question. Do you say the man was holding the officer's horse, and when the officer came and took his horse he shot the man down?

Answer. Yes, sir; I saw that with my own eyes; and then I made away into the river, right off.

Question. Did you see any buried?

Answer. Yes, sir; a great many, black and white.

Question. Did you see any buried alive?

Answer. I did not see any buried alive.

Aaron Fentis, (colored,) company D, 6th United States heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By the chairman:

Question. Where were you from?

Answer. Tennessee.

Question. Have you been a slave?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. Where did you enlist?

Answer. At Corinth.

Question. Who was your captain?

Answer. Captain Carron.

Question. Were you in the fight at Fort Pillow?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. What did you see done there?

Answer. I saw them shoot two white men, and two black men, after they had surrendered.

Question. Are you sure they were shot after they had surrendered?

Answer. Yes, sir. Some were in the river swimming out a piece, when they were shot; and they took another man by the arm, and held him up, and shot him in the breast.

Question. Did you see any others shot?

Answer. Yes, sir; I saw two wounded men shot the next morning; they were lying down when the secesh shot them.

Question. Did the rebels say anything when they were shooting our men?

Answer. They said they were going to kill them all; and they would have shot us all if the gunboat had not come along.

Question. Were you shot?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Question. When?

Answer. After the battle, the same evening.[Pg 25]

Question. Where were you shot?

Answer. Right through both legs.

Question. How many times were you shot?

Answer. Only once, with a carbine. The man stood right close by me.

Question. Where were you?

Answer. On the river bank.

Question. Had you arms in your hands?

Answer. No, sir.

Question. What did the man say who shot you?

Answer. He said they were going to kill us all.