BOOKS

BY GERTRUDE L. STONE AND

M. GRACE FICKETT

EVERY DAY LIFE IN THE COLONIES

DAYS AND DEEDS A HUNDRED

YEARS AGO

FAMOUS DAYS IN THE CENTURY OF

INVENTION

D. C. HEATH & CO., PUBLISHERS

FAMOUS DAYS IN THE

CENTURY OF INVENTION

BY

GERTRUDE L. STONE

INSTRUCTOR IN THE STATE NORMAL SCHOOL

GORHAM, MAINE

AND

M. GRACE FICKETT

INSTRUCTOR IN STATE NORMAL SCHOOL

WESTFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS

D. C. HEATH & CO., PUBLISHERS

BOSTON NEW YORK CHICAGO

Copyright, 1920,

By D. C. Heath & Co.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | How the Sewing Machine Won Favor | 1 |

| II | Long-Distance Talking | 30 |

| III | A New Era in Lighting | 48 |

| IV | The Triumph of Goodyear | 67 |

| V | The Easier Way of Printing | 92 |

| VI | Anna Holman's Daguerreotype | 111 |

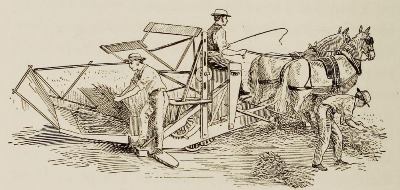

| VII | The Story of the Reaper | 124 |

| VIII | Grandma's Introduction to Electric Cars | 138 |

"It is! It is!" chattered the robins at half past three on an early June morning in 1845. Jonathan Wheeler sat up in bed with a start. This was the morning he had been waiting for all the spring, the morning he was to start for Boston with his father, mother, and Uncle William, and ride for the first time on a railway train.

"Is it really pleasant?" was his first thought. "It is! It is!" chirped the robins again. And Jonathan's eyes by this time were open enough to see the red glow through the eastern window. In a second he was out of bed, hurrying into his best clothes that his mother had laid out for him the night before.

Jonathan lived in a little town only thirty miles [Pg 2]from Boston; but traveling was not then the easy and familiar experience of to-day. The nearest railway station was at South Acton, fifteen miles away. The Wheelers had planned to start from home in the early morning, and after dining with some friends in the railroad town, leave there for Boston on the afternoon train.

But in those days the Fitchburg railroad had not crossed the river, and had its terminal at Charlestown. From there passengers were carried by stage to the City Tavern in Brattle Street. It would be six o'clock that night before Jonathan could possibly see Boston.

But he lost no moment of his longed-for day. The bothersome dressing and eating were soon over; and Jonathan felt that his new experiences were really beginning when, at seven o'clock, from the front seat beside his father in the blue wagon, he looked down on his eight less fortunate brothers and sisters and several neighbors' children, who, with the hired man, were waiting to see the travelers depart.

"Good-bye! Good-bye, everybody!" called Jonathan, proudly. "I shan't see you for three days, and then I shall be wearing some store clothes!"

For the first few miles the conversation of his elders did not interest him much. He was so busy watching for the first signs of a railway train that [Pg 3]the smoke from every far-away chimney attracted his attention; but after a while, when there was nothing to see but the thick growths of birch and maple each side the road, he heard his father saying:

"Well, Betsey, I think thee has earned this holiday. Thee has had a busy spring."

"It has been a busy time," agreed Mrs. Wheeler. "But all the house-cleaning is done and every stitch of the spring sewing. Since April I've cut and made sixteen dresses and six suits of clothes."

"Did thee read in the Worcester Spy last week, Betsey," inquired Uncle William, "of a sewing machine that bids fair to be a success?"

"A sewing machine!" echoed Mrs. Wheeler. "Does thee mean a machine that actually sews as a woman sews? That's too good to be true!"

"But it's bound to come, Betsey," said her husband reassuringly. "We're keeping house to-day much as the early settlers did. We've found better ways of travel, and labor-saving inventions are the next thing." Then, turning to his brother, he added, "Tell us, William, what the Spy said."

"Well, it seems there's a young man in Boston who has a good deal of ingenuity, and he actually has a sewing machine on exhibition at a tailor's there. For some days he's been sewing seams with it, the paper said, at the rate of three hundred stitches to the minute. Perhaps we shall find that tailor's shop to-morrow."

"I should like nothing better," answered Mrs. Wheeler. "Maybe we can buy Jonathan's trousers there."

Jonathan had been an interested listener to this conversation; but just then he caught sight of a moving column of smoke, and for the rest of the drive he thought of little else but the engine he could scarcely wait to see. By ten o'clock came South Acton; then the long hours while his elders ate slowly and talked much; at last the wonderful, puffing, noisy engine and the strange, flat-roofed houses on wheels with their many little windows. Jonathan's world had grown very large indeed when he went to sleep that night at the City Tavern in Brattle Street.

The next morning at the breakfast table, with the aid of the Morning Advertiser and the Boston Transcript of the night before, the Wheelers made their plans for the day's shopping and sight-seeing.

"We'll do the shopping first," decided Mrs. Wheeler. "Here's an advertisement of ready-made clothing." And she read aloud what was, for those days, a rather startling advertisement, beginning:

PERPETUAL FAIR

AT

QUINCY HALL

OVER QUINCY HALL MARKET

BOSTON

"Let's go there," advised Uncle William. "Quincy Market isn't far from here." So the Wheelers' first stopping place that morning was Mr. Simmons's establishment at Quincy Market.

"Has thee any linen trousers for this little boy to wear with the dark blue jacket he has on?" inquired Mrs. Wheeler of the young man who came forward to serve them.

"We have, madam, I am sure." And deftly the polite young man picked out a pair of dark blue and white striped linen trousers from the middle of a neat pile of garments. Sure enough, the trousers were of the right size; and, to the Wheelers' astonishment, [Pg 6]the price was less than they had expected to pay.

"There must be some profit, madam, you see," explained the clerk; "but if we could make these garments by machine, as a young man in the next room says he can, we could afford to sell them for almost nothing."

"We have heard of that young man and his machine. Will it be possible for us to watch him sew with it?" replied Mrs. Wheeler.

"Certainly, madam. Just step this way, if you please." And he ushered the Wheelers into an adjoining workshop, well filled with men and women, many of the men, as Jonathan found out later, being dealers in ready-made clothing in the larger towns near Boston.

"Oh, mother, there he is!" whispered Jonathan excitedly, and he hurried forward to see better.

A kindly-faced young man, not more than twenty-five years old, sat at a table before what seemed to Jonathan a sort of little engine without wheels. With one hand he was turning a crank and with the [Pg 7]other he was guiding a seam on a pair of overalls. A bright needle flashed in and out of the blue cloth till it reached the end of the seam. Then the sewer stopped the machine, cut the thread, and handed the garment about for inspection.

"That took just one minute, Mr. Howe," announced a man who stood near, watch in hand.

"One minute!" echoed a woman standing beside Jonathan. "I could not sew that seam in fifteen minutes."

"How long would it take thee, mother?" whispered Jonathan, aside.

"I'm not sure, little boy," his mother whispered back. "I think I could do it in ten minutes."

"An experienced seamstress could not sew that seam in less than five minutes," then spoke Mr. Howe, as if in answer to a question.

"I don't quite believe that," objected one man.

"Well, why not have a race?" challenged Mr. Howe. "Mr. Simmons," he continued, addressing the proprietor, "will you let five of your best sewers run a race with me? I'll take five seams to sew while each of them does one. Are you willing?"

"Agreed!" said Mr. Simmons. And it was but the work of a moment to select an umpire and prepare the seams. Then the umpire gave the command to start and the race began.

It was an exciting contest. The girls sewed "as fast as they could, much faster than they were in the habit of sewing." Mr. Howe worked steadily but carefully.

"If he wins, how many times as fast as each girl is he sewing?" asked Jonathan's uncle suddenly, of the little fellow. Jonathan was too bright to be caught and answered quickly, "More than five, isn't he?"

"That's right, Jonathan. And he really is sewing more than five times as fast. Look!"

It was true. Mr. Howe held up his finished seam. Every girl was still at work. "The machine has beaten," announced the umpire. "And moreover," he added after careful inspection, "the work on the machine is the neatest and strongest."

"Now, gentlemen," said Mr. Howe, "may I not have your orders for a sewing machine? See what a money-saver it will be! I can make you one for seven hundred dollars. It will pay for itself in a few months, and it will last for years."

Jonathan expected to hear many of the tailors present order a machine at once. But he was witnessing, although he did not know it till years afterward, "the pain that usually accompanies a new idea." The invention which was to make the greatest change of the century in the manufacturing world lay for several years unused and scorned [Pg 9]by the public. The short-sighted tailors over Quincy Hall Market made one objection after another.

"It does not make the whole garment."

"My journeymen would be furious."

"Truly, it would beggar all handsewers."

"We are doing well enough as we are."

"It costs too much."

"Why, Mr. Howe, I should need ten machines. I should never get my money back."

Jonathan was sorry for Mr. Howe. "I'll buy a machine some day," he announced.

"Thank you, little boy," answered Mr. Howe. "I've no doubt you will."

But the tailors laughed and shook their heads.

Before they left the workshop, Jonathan's party had a long talk with Mr. Howe.

"We are from the country," they said, "with no money to buy a machine of this sort. But we are interested in it, and we believe it has a future. Will thee tell us more about it?"

"Gladly," said Mr. Howe. "I've been at work on the machine most of the time for the last five years—ever since I was twenty-one, in fact. I was born up in Worcester County, in Spencer. When I was eleven, I was bound out to a farmer, but I liked machinery better. I went to Lowell as soon as my parents were willing, and worked a while in a cotton mill. But I did not like that very well, it was so monotonous, and I came down here to work for Mr. Davis in Cornhill. One day a man who was trying to construct a knitting machine came in to see if Mr. Davis could make him a suggestion. But Davis really made the suggestion to me. 'Why don't you make a sewing machine?' he asked.

"'I wish I could,' the man answered, 'but it can't be done.'

"'Oh, yes,' cried Davis, 'I could make one myself.'

"'Well,' was the rejoinder, 'you do it, Davis, and I'll insure you an independent fortune.'

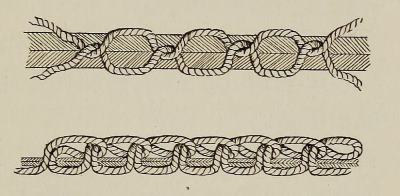

Lock Stitch (above) and Chain

Stitch (below)

The lock stitch is made with two threads, and

the chain stitch with one.

"Now I don't know that Davis or the other man has thought of the matter since. As for me, I've thought of little else. A year ago last October I had planned out the chief parts of the machine—the two threads, the curved, eye-pointed needle, and the shuttle. A rough model that I made convinced me that such a machine would work; and last December I prevailed upon my friend, Mr. Fisher of Cambridgeport, to let me, with my wife and children, live at his house and construct my machine in his garret. He gave me five hundred dollars besides for material. In return for those favors, I've agreed to give Fisher half my profits. But," he added rather gloomily, "so far it's been a bad bargain for Fisher."

"Is the machine patented?" inquired Uncle William.

"Not yet," answered Mr. Howe. "I need some money first, for, you know, I shall have to make a model to deposit at Washington."

The Wheelers thanked Mr. Howe for his kindness in satisfying their curiosity and wished him all good fortune.

"Sometime," added Jonathan's father, "I expect thy machine will find its way into homes as well as into shops."

"Indeed, Mr. Howe," added Mrs. Wheeler, "it would be the greatest boon the farmer's wife could ask."

"I prophesy, Betsey," said Uncle William, "that before many years thee will make Jonathan some overalls with a machine of thine own. Meantime," turning to Mr. Howe, "I want to buy him the pair thee sewed in the race. They were boys' trousers, were they not?"

"Yes," answered Mr. Howe, "and I'm sure Mr. Simmons will be glad to sell them to you. He does not put too high a value on them, you know," he added soberly. "Anyway, I shall be glad to know that my machine has sewed for so engaging a little fellow," he finished, with a pleasant smile.

As for Jonathan, he was almost too excited to speak. Two new pairs of "store" trousers in one day, and one of these sewed by a machine! "Thank you, Uncle William," he gasped. And he must say something to Mr. Howe. "Thank you, too, Mr. Howe. I shall surely buy a machine some day."

Jonathan returned to the country the next day, a much traveled little boy for the year 1845. All [Pg 13]his experiences remained vividly in his memory: the wonderful railway train, the stage coach clattering over the city pavements, the waiter at the hotel who stood politely near the table and anticipated his wants—all these recollections made his farm life happier and his farm tasks easier. Of all his Boston memories, however, none were more vivid or more persistent than the sight of that marvelous sewing machine and its exciting race with the skilled sewers.

"What has become of Mr. Howe?" thought Jonathan more than once. "Has he given up trying to persuade people that sewing by hand was often a needless drudgery?" For a year and a half Jonathan could only wonder. Then, one day in February, 1847, Uncle William read in the Boston Advertiser that Elias Howe and his brother had taken passage in a packet for England to interest Londoners in the curious machine that could work faster and more skillfully than human fingers.

Three years later Uncle William took Jonathan on another journey, this time to a small town west of Worcester and about thirty miles from home. The trip was made, so Uncle William said, to consult with a county commissioner there about the prospect of a much needed road; but Mrs. Wheeler, [Pg 14]when she remembered that Mr. Howe had mentioned Spencer as his birthplace, remarked knowingly to her husband:

"Not that I would question Brother William's motive, but thee knows, Daniel, that he was the most interested man in that room over the Quincy Hall Market. He may need to see the commissioner, but I think he's more interested in the fortunes of young Howe."

"I believe thee's right," answered her husband. "And I hope," he added, "that William will come [Pg 15]back with good news about that young fellow and his machine."

There was no railway train this time for Jonathan. It was an interesting journey, nevertheless, through a beautiful hill country with varied scenery. Jonathan and his uncle both enjoyed their ride in the comfortable one-horse chaise and their dinner at the Worcester inn. In the afternoon they drove out to Spencer and put up at the tavern there; and after supper they went to bed in the very room where President Washington once had slept.

"Now, if I could only see Mr. Howe on the street to-morrow morning!" thought Jonathan as he dropped asleep.

Mrs. Wheeler would not have been greatly surprised at Uncle William's procedure the next morning. The visit to the county commissioner was made immediately after breakfast and the information that Uncle William desired easily and quickly obtained.

"By the way," inquired Uncle William when the business interview was over, "do you know anything of a young fellow named Elias Howe?"

"Elias Howe? Why, yes, I believe so. There are so many Howes here I had to think a minute. You mean Elias, Jr., I guess. They did live down in the south part. The young fellow had some [Pg 16]scheme of sewing by machinery. Couldn't make it work, I believe."

"Is his father living here?"

"No, not now. Another son invented a machine for cutting palm leaf into strips for hats and Howe moved to Cambridge to help the thing along. Don't believe he'll ever come back."

"My nephew and I saw young Howe in Boston four years ago with his sewing machine. We've both been much interested to hear more about his fortunes. Has he some relatives here who could tell us?"

"Why, yes, his uncle Tyler lives here, his father's brother. His house is right over there. Better call on him. He's a pleasant fellow—every Howe is—and he likes to talk."

"Shall we?" asked Uncle William of Jonathan.

Jonathan's feeling in the matter was not uncertain, but all he said was, "I should like to, Uncle."

"Glad to see you both," was the hearty greeting of Mr. Tyler Howe, upon hearing Uncle William's introduction of himself and his nephew. "Well, Elias is a smart boy and a good one, but he's pretty well down on his luck just now. So you saw him in Boston? Four years ago, wasn't it? Since then he's had a discouraging time.

"After he exhibited his machine in the shop where you saw him, he spent three or four months [Pg 17]in Fisher's garret, making another machine to deposit in the patent office. The next year he and Fisher went to Washington, where they had no trouble in getting a patent, but no luck at all in interesting people in the sewing machine. They exhibited it once at a fair, but the crowd was amused, that's all.

"By the time Fisher got back to Cambridge, he washed his hands of the whole matter. I don't much wonder. He'd spent all of two thousand dollars and hadn't had a cent in return. Then Elias had only his family to turn to. With his wife and children he moved to his father's and began to plan how to interest England in the invention America had rejected.

"He made a third machine, and with that as a sample, his brother Amasa sailed for England in October, about a month after Elias came back from Washington. For a time it seemed as if the trip would be worth while. Amasa showed the machine to a William Thomas, who had a shop in Cheapside, where he manufactured corsets, umbrellas, carpet bags, and shoes. You can see that the sewing of such articles must be extremely difficult, and Thomas was really interested in the machine.

"But Amasa, I'm afraid, hasn't proved himself much of a business man. He sold Mr. Thomas outright for two hundred fifty pounds sterling (that's [Pg 18]twelve hundred fifty dollars of our money, Jonathan) the machine he had brought with him and the right to use as many more as were necessary in the business."

"Then the notice in the paper was a mistake. So Elias didn't go to Europe?" inquired Uncle William.

"Yes, the notice was true. You see, the man Thomas did most of his trade in corsets, and the machine was better adapted to sewing overalls and shirts. So Thomas agreed to give Elias three pounds a week if he would go over to London and adapt the machine for use on corsets and other stiff material. Thomas also agreed to pay the expenses of workshop, tools, and material.

"Amasa came back to America with this news, and then he and Elias, with the precious first machine, started together for London in February, just as the paper said. They had so little money that they had to go in the steerage and cook their own food. But in London things went well for a time, and Thomas even advanced the money for Elias's family to join him. However, the good fortune was short-lived. In eight months Elias had adapted his machine to Thomas's requirements, and then Thomas ungratefully discharged him for good and all.

"Things were pretty dark for Elias by this time. Thomas had agreed, but only by word of mouth, to patent the invention in England, and to pay Elias three pounds on every machine that was sold. There are scoundrels everywhere, I suppose; but that Thomas has proved one of the meanest men I ever heard of. Sewing machines are fairly common in London now, and on every one of those Thomas has realized about ten pounds, but Elias hasn't had a shilling.

"Of course, when Thomas discharged him, he had nothing to do but move his family into cheaper quarters, borrow a few tools, and begin the construction of a fourth machine. He could not finish it without more money, so he moved his family into one very small room and worked as fast as he [Pg 20]could. But even then he could not buy food for his wife and children and material for his machine. There was nothing to do but send his family home and work at the machine till he could sell it and get his own passage money.

"Elias has been in a good many straits for a young fellow, but he has a marked gift for making friends. At this time he grew to know pretty well a coach maker, named Charles Inglis, who unfortunately was a poor man too, but who often lent him what money he could during those evil days, and what was better, kept faith in him.

"The night that Mrs. Howe and the children left England, it was so very wet and stormy that Mrs. Howe, who was almost in consumption, could not walk to the ship. Inglis lent Elias a few shillings for the cab hire, and Elias promised him some clothing in return. The clothing was what the washerwoman had brought home that morning, but had taken away again, because there was no money to pay her.

"Then came days of pinching poverty for Elias; but not quite such unhappy ones, I think, now that the wife and children were soon to be with the relatives in Cambridge. Elias knew that the Howes were too proud to let his family starve; and as for himself, he would borrow a shilling at a time of Inglis and buy beans to cook in his own room.

"Finally he finished the machine. Instead of getting the fifty pounds that it was worth, he had to sell it for five pounds, and even then for a mere promise to pay. Inglis soon managed to get four pounds of the money in cash for him, but that four pounds was by no means enough to pay Elias's debts and buy his passage. There was nothing to do but pawn his precious first machine and the letters-patent. That done, he drew his baggage on a hand cart to a freight vessel, and he and Inglis took passage in the steerage of another ship bound for America.

"Elias reached New York last April with half a crown in his pocket, but he found employment in a machine shop almost at once. Then came the sad news that his wife, who had been ill when she left England, was dying in Cambridge.

"Elias had no money for a railroad journey. He had to wait friendless, except for Inglis, in a great city, wholly despairing of ever seeing his wife again and feeling that he had risked everything to gain [Pg 22]nothing. His father, however, as soon as he knew of his destitution, sent him ten dollars, and Elias reached Cambridge just in time to speak to his wife before she died. He had no clothes, though, but his shabby working suit, and could not have gone to the funeral if his brother had not lent him a coat.

"That was the last time I saw Elias, and then I should scarcely have known him. By nature, he is, you know, a pleasant-faced, happy fellow; but then he looked as if he had had a long, painful sickness. There wasn't a trace of his old self left. And as if he hadn't had trouble enough, word arrived before I left Cambridge that the vessel to which he had carted his household goods had been wrecked off Cape Cod.

"Most people would have given up, I think, under all these trials, but Elias has a good deal of the Howe perseverance. He immediately got a position in Boston as a journeyman machinist at weekly wages."

"And where is he now?" inquired Uncle William sympathetically.

"I had a letter from him the other day. Should you like to hear it?"

Taking the answer for granted, Mr. Howe opened his desk and took out the letter. Then he read as follows:—

Cambridge, Mass., June 20, 1849

My dear Uncle,

You will be interested, I know, in what I have to write; and I think you will agree with me that I shall yet retrieve all my ill-luck. Any advice you may have for me I shall cheerfully receive.

First look at the enclosed hand bill.

And Mr. Howe interrupted the reading to pass Uncle William and Jonathan a small hand bill like this:—

A GREAT

CURIOSITY!!

THE

YANKEE SEWING MACHINE

IS NOW

EXHIBITING

AT THIS PLACE

FROM

8 A.M. TO 5 P.M.

He then went on with the reading:—

That was posted about in Ithaca, N. Y., just a few weeks after I came back from England.

Some fellow made a machine from the description he heard of mine, and he has been giving exhibitions of its work in various places. He says his machine can do the work of six hands and make a pair of pantaloons in forty minutes. And I have no doubt he tells the truth.

Only, Uncle Tyler, don't you see it's my machine and he is infringing on my patent? And more than that, right here in Boston machines have been built on my model and are in daily use. Now I know that I am without resources and that I have pretty well exhausted the patience of my friends. But surely my claims are valid.

Getting money to push them is the task I dread. Still I have already raised a hundred dollars to get my machine and letters patent out of pawn in London; and I have every hope that Mr. Anson Burlingame, who is soon to sail for England, will deliver them safely to me in the fall.

The next step is to see if the lawyers can find any flaws in my claims. If they can't, the suit I propose to bring is already in my favor; and I am sanguine enough to believe that the Howe sewing machine will yet be a household convenience.

Yours respectfully,

Elias Howe, Jr.

"Well," commented Mr. Howe, as he folded the letter slowly, "I didn't know how to answer that. He said he wanted advice. I know he wants money more, but of course he hates to ask for it. I deliberated a good while; but finally I wrote him that if the lawyers gave him assurance that his claims were valid, I would advance what money I could spare to further his suit."

There was silence in the room for a little while. Then Jonathan said earnestly:

"I wish I had some money to give Mr. Howe. Would he take my five dollars, do you think?" he asked of the inventor's uncle.

"See, I have it here; and I should be glad to give it to him without waiting to hear what the lawyers say. Do you think it would be all right to send it, Mr. Howe?" he inquired.

"And may I, Uncle William?" he added quickly, for he had almost taken his uncle's permission for granted.

Uncle William nodded; and Mr. Howe said, "You may never get it back, you know."

"I think I shall," answered Jonathan confidently. "And anyway I want to help Mr. Howe."

"Do you want to send it now?" inquired Mr. Howe.

"If you please," replied Jonathan.

"Then you may write your letter here, while your uncle and I go for a walk."

Spencer, Mass.,

15th 9th mo., 1849.

Mr. Elias Howe, Jr.,

Cambridge, Mass.My dear Mr. Howe:—

Perhaps thee remembers the boy who saw thee run a race with thy sewing machine against five seamstresses over Quincy Hall Market four years ago. Thy uncle told me of the hard time thee has had since. I am very sorry. I want to buy a sewing machine and I want to help thee. I am sending thee five dollars. It is all the money I have. I hope thee will use it to win thy suit. Sometime when thee sells sewing machines, I hope thee will sell me one for my mother five dollars less than the usual price. Thee can see thee will not have to pay this back for a long time, for it will be a good many years before I shall have money enough to buy a sewing machine.

Thy friend and well-wisher,

Jonathan Wheeler

There is little more to tell of Jonathan's visit to Spencer. After dinner that day he started with his uncle for Worcester, where they stayed all night. The next morning, after an early breakfast, they set out again, reaching home before the forenoon grew very hot.

Not many days after Jonathan's return, the first letter he ever received his father brought him from the post office. It hardly needed the post mark, Cambridge, to make Jonathan sure who had sent it. Let us open it with him:—

Cambridge, August 26, 1849.

My dear friend Jonathan,

Your letter with its inclosure of five dollars has been gratefully received. I remember you and your uncle, your father and your mother, with much pleasure. Ever since I ran that race in Boston I have been sure that the machine would work its way to success.

I am more confident now than ever. I have found some one who will buy out Mr. Fisher's interest; Mr. Burlingame will bring my old machine and letters patent from London; and every lawyer I have consulted says my claims are valid and I shall win my suit.

When I have succeeded, and the manufacture of sewing machines is under my control, I shall send for you to pick out a machine for your mother.

Again thanking you for your substantial interest, I am

Very faithfully yours,

Elias Howe, Jr.

This was in 1849. Mr. Howe's darkest days were over; but even then success came slowly and in rather a strange way. Mr. Howe's chief enemy was a Mr. Singer, who built machines and advertised them with remarkable success.

"You are infringing my patent," wrote Howe to Singer, upon hearing of the latter's activity.

"But you are not the inventor," replied Singer. "The Chinese have had a sewing machine for ages; an Englishman made one in 1790; a Frenchman built one in 1830; and what is more to the point, in 1832, a man named Walter Hunt, living in New York, invented a sewing machine with a shuttle stitch like yours. I can find Walter Hunt and prove my statement."

Well, Mr. Singer did find Walter Hunt and the fragments of his old machine. But "not all the king's horses nor all the king's men" could put those fragments together again so that the machine would sew. For four years, however, the trial in the courts continued. But at last, in 1854, when Mr. Howe had waited nine years after completing his first machine, the Wheelers and many others read with great satisfaction in the Worcester Spy:

"Judge Sprague of Massachusetts has decided that the plaintiff's patent is valid and that the defendant's machine is an infringement. Further, there is no evidence in this case that leaves a [Pg 29]shadow of a doubt that, for all the benefit conferred upon the public by the introduction of a sewing machine, the public are indebted to Mr. Howe."

In 1855, Jonathan, now grown into a tall, manly youth of twenty, started with Uncle William on another journey, longer and more interesting than either had ever taken before. This time they went to New York, where they found Mr. Howe at the head of a prosperous business; and when they returned, they brought with them a Howe sewing machine of the very latest model, "a present from the inventor to Mrs. Wheeler, in gratitude for the sympathy and encouragement of her family."

Late one June afternoon Arthur Burton was leaning against a table in the eastern gallery of the main hall at the Philadelphia Exposition. It had been a wonderful day, but it was past dinner time, and he was hot, tired, and hungry. He had seen more wonders that day than he had witnessed in all his life before; but now his uncle and the other judges were in the midst of the Massachusetts educational exhibit, which wasn't half so interesting as the first electric light, or the first grain reaper, or the iceboats. So Arthur had moved away from the new-fashioned school desks and the slate blackboards, and was waiting rather wearily.

Suddenly he straightened up. Entering the door near by was the most distinguished visitor at the Centennial, the tall, handsome Dom Pedro, Emperor of Brazil, with the Empress and a bevy of courtiers. To Arthur's amazement, His Majesty walked directly up to the table against which he himself was standing; and looking beyond the [Pg 31]little boy, he said with outstretched hand and a pleasant smile:

"How do you do, Mr. Bell? I am very glad to see you and your work."

Till then Arthur had scarcely noticed a sallow, dark-haired young man who had been sitting behind the little table, nor had he paid the slightest attention to some pieces of wood and iron with wire attached lying on the table. But now, the young man and his material had become decidedly interesting.

"I remember very pleasantly," continued Dom Pedro, "my visit to your class in Boston University when you were teaching deaf mutes to speak by means of visible speech. You were working out a new method, I remember. I suppose this is apparatus that you have devised in that connection."

"I thank Your Majesty," stammered the surprised young man, who for a moment had been [Pg 32]at a loss to recall who his royal visitor might be. "I shall be delighted to explain my apparatus. But it has nothing to do with teaching deaf mutes to speak. It is more wonderful than that. It speaks itself; that is, it reproduces sounds. It is the improvement on the telegraph that the world has awaited for years.

"You see, I found in my experiments that I could transmit spoken words by electric current through a telegraph wire so that those words could be reproduced by vibrations at the other end of the wire. I suppose my invention might be called a speaking telegraph."

By this time all the judges had joined the Emperor's party. Arthur fell back to his uncle's side, but he could still hear and see everything.

"Now, Your Majesty," continued Mr. Bell, "if you will press your ear against the lid of this iron box, I think in a moment you will have a surprise."

At these words, Mr. Bell's assistant, who had come up to the group during the conversation, went to another table several rods away and quite out of hearing. The Emperor bent down expectantly. The judges looked rather incredulous, but they were all interested.

"Is the man that went off going to talk over the wire so that the Emperor can hear?" whispered Arthur to his uncle.

"Mr. Bell says so," was the reply, "but we shall see."

Suddenly the Emperor gave a start, and a look of utter amazement came over his face.

"It talks! It talks!" he exclaimed excitedly.

It was quite true. Mr. Hubbard, Mr. Bell's assistant, had spoken in a low voice at the other end of the wire and his exact words had been reproduced. The Emperor's excitement was contagious. Everybody forgot how hot and hungry he was. One after another of the judges listened at the magic box to hear Mr. Hubbard or another of their number speak into the instrument at the other end.

"Oh, Uncle, do you suppose I can listen too after a while?" inquired Arthur, when he could no longer keep still.

Just then Mr. Bell himself interposed.

"Now it must be the little boy's turn."

The grateful little boy was not slow in stooping over to the receiver.

"What does he say, Arthur?" asked his uncle.

"Why, he says, 'To be or not to be,' whatever that means."

"You don't know your Hamlet very well yet, little boy."

"But I have heard a speaking telegraph, and that is better," replied Arthur.

By this time Mr. Hubbard was returning with the apparatus he had been using at the other end. It was time to see how the marvel had been wrought.

"Now tell us how it works, Mr. Bell," commanded Dom Pedro.

"It is very simple," Mr. Bell explained. "You know, of course, that for some years it has been possible to transmit articulate speech through India rubber tubes and stringed instruments for short distances; but I worked, as you see, to transmit spoken words by electric current through a telegraph wire.

"Here on the table before you is the instrument I call the transmitter, into which Mr. Hubbard spoke. This projecting part is only a mouth-piece. Inside is a piece of thin iron attached to a membrane, and this piece of iron vibrates whenever one speaks into the transmitter. For you know, gentlemen, that if you hold a piece of paper in front of your mouth and then sing or talk, the paper will vibrate as many times as the air does.

"Now, of course, if I could reproduce those sound or air waves at a distance, a person listening would hear the same sounds that caused the first vibration. I have accomplished that by making and breaking an electric current between two pieces of sheet iron. My assistant spoke into the cone-shaped mouth-piece. At the end of it, as you could [Pg 35]see if I took off the cover, is the first thin plate of sheet iron. Near that iron, but not touching it, is a magnetized piece of iron wound around with a coil of wire.

"This magnet is connected by this wire with another magnet that also has a coil of wire around it. On the other side of the second magnet is the other thin plate of sheet iron. This last part makes what I call the receiver. It is the part at which you listened. It looks, you see, like a metallic pill box with a flat disc for a cover, fastened down at one side and tilted up on another. When you put your ear to that, you heard the reproduction of the original sound."

"Marvelous!" "Wonderful!" "Stupendous!" "Incredible!" were some of the exclamations.

"But, gentlemen," confirmed one of the judges, a man named Elisha Gray, "it is perfectly true. I myself have an invention of a similar sort, by which I can send musical sounds along a telegraph wire."

There was a moment of amazement and congratulation for Mr. Gray. Then came a question addressed to Mr. Bell.

"Could you talk into the iron box and hear at the transmitter?"

"Yes, but not easily. So far I have had to use different instruments at each end of the circuit. I shall remedy that some day," continued Mr. Bell, confidently.

"I am sure you will," agreed the questioner. "We want to see this again, sir," spoke one of the group. "May it not be transferred to the Judges' Hall?"

"Certainly, as far as I am concerned," was the reply. "Mr. Hubbard will see to that, I am sure. I myself must return to Boston to-night."

"My young friend," now spoke Sir William Thomson (who later became Lord Kelvin), perhaps the most noted of all the scientists present, "is it not possible to arrange for a test with your apparatus over a considerable distance? If so, I shall be glad to go to Boston also to witness such an experiment."

"I shall be most delighted, Sir William," answered Bell. "I will make the necessary arrangements and telegraph you at once."

After more congratulations for the young inventor, the group dispersed, the judges going away [Pg 37]to the dinner they had for a while forgotten. But during the meal and through the evening they talked of little but the new invention; and Arthur distinctly remembers to this day the enthusiastic remark of Sir William Thomson: "What yesterday I should have declared impossible I have to-day seen realized. The speaking telegraph is the most wonderful thing I have seen in America."

When Arthur went back to his home in one of the country towns of Massachusetts, he had many things to tell his family and his friends. To him the Exposition had been a veritable fairy land. But the most wonderful genie there was Electricity, and his most remarkable work was the speaking telegraph.

"And you could really hear through that wire?" questioned more than one incredulous person.

"I really could, and as plainly as I hear you," insisted Arthur.

"Sho, now!" remonstrated a farmer neighbor, "you only thought you could."

"Well, maybe," commented another, cautiously, "but of course there was a hole in the wire that you didn't see."

Arthur's own family were more thoughtful and intelligent people.

"I knew," said Grandfather, "that the marvels of electricity were not all understood. When I was a young man, the telegraph was the greatest wonder the world owned. But using that was somehow like talking at arm's length; the telephone brings your friend almost beside you."

"To me," said Arthur's mother, "the telephone, in comparison with the telegraph, seems like a highly finished oil painting. The old invention is like a page of black and white print."

"Why, I have seen Mr. Bell," remembered Arthur's older sister, who was studying to be a teacher, after she had heard the story. "He came to the normal school last year to explain his system of teaching deaf mutes to speak."

The Burtons heard no more of the telephone for six months or more; but the next winter, when Herbert, the older brother, came home from Tufts College to spend a week end, he exclaimed:

"Well, Arthur, I've talked through a telephone, too!"

"You have!"

"Where?"

"Tell us about it!" were the quick replies.

"Professor Dolbear, the physics instructor, has made one in his laboratory. It's a little different from Professor Bell's. Your professor, Arthur, [Pg 39]had a battery, you know, to make the electro-magnet. My professor has a permanent magnet instead."

Early in February Herbert came home with more news and an invitation: "Professor Bell is going to give a public lecture and exhibition of his telephone at Salem next Monday evening. He expects to carry on a conversation with people in Boston. Want to go back to college with me Monday morning, Arthur, and go down to Salem in the evening?"

So it happened that on Monday evening, February 12, 1877, Arthur and Herbert, with about five hundred others, were at Lyceum Hall in Salem. It was an eager audience, full of curiosity.

Upon the platform and well toward the front was a small table, on the top of which rested an unimportant-looking covered box. From this box wires extended above to the gas fixture and out through the hall. At the back of the platform was a blackboard on a frame, and at the side a young woman, an expert telegrapher, who was to help Mr. Bell.

"Rather an unpromising set of apparatus!" Arthur heard a man behind him whisper to his neighbor.

"I'm not expecting much," returned the neighbor. "They say Professor Bell's going to talk to Boston. That's nonsense!"

But just then Professor Bell began. He briefly [Pg 40]explained the instrument upon the table, which, Arthur saw, varied but little from that at Philadelphia.

"Only," thought Arthur, "he uses it now as he said he should, for transmitting and receiving too."

Then Professor Bell gave a brief account of the studies he had made since 1872, when he came to Boston to teach speech to deaf mutes.

"I made up my mind," said he, "that if I could make a deaf mute talk, I could make iron talk. For two years I worked on the problem, but unsuccessfully. At last, about two years ago, while a friend and I were experimenting daily with a wire stretched between my own room at Boston University and the basement of an adjoining building, I spoke into the transmitter, 'Can you hear me?' To my surprise and delight the answer came at once, 'I can understand you perfectly.' To be sure," continued the lecturer, "the sounds were not perfect, but they were intelligible. I had transmitted articulate speech.

"My problem was a long way toward its solution. With practically those same instruments, improved with a year's experimenting, I went to the Exposition, where, as you know, I interested many people. Since last June Sir William Thomson and I have succeeded in talking over a distance of [Pg 41]about sixty miles. Moreover, I have talked, but not so successfully, between New York and Boston, a distance of over two hundred miles. To-night I expect to establish a connection between this hall and my study in Exeter Place in Boston, eighteen miles away. My colleague, Professor Watson, is there, in company with six other gentlemen."

Then, in an ordinary tone, as if speaking to some one a few feet away, Professor Bell inquired, talking into the transmitter:

"Are you ready, Watson?"

Evidently Watson was ready, for there came from the telephone a noise much like the sound of a horn.

"That is Watson making and breaking the circuit," explained Professor Bell.

Soon Arthur heard plainly the organ notes of "Auld Lang Syne," followed by those of "Yankee Doodle."

"But that's not the human voice," objected Arthur's neighbor to his companion. "Musical sounds we know can be telegraphed."

Just then Mr. Bell spoke again into the transmitter.

"Watson, will you make us a speech?"

There came a few seconds of silence. Then, to the astonishment of all, a voice issued from the telephone. All the five hundred people could [Pg 42]hear the sound, and those less than six feet from the instrument had little difficulty in making out the words:

"Ladies and gentlemen: It gives me great pleasure to address you this evening, though I am in Boston and you are in Salem."

"I wonder what those men think now," reflected Arthur.

But the answer was forthcoming.

"We can no longer doubt. We can only admire the sagacity and patience with which Mr. Bell has brought his problem to a successful issue."

At the conclusion of the lecture many of the audience went to the platform to examine the wonderful box more closely. Arthur and Herbert were of the number, you may be sure.

"Is it all right for me to speak to Mr. Bell, Herbert?" whispered Arthur.

"Certainly, if you don't interrupt."

Arthur watched his chance.

"Mr. Bell," he said finally, "you did make the receiver into a transmitter, didn't you? I saw you at Philadelphia, you know."

Mr. Bell's puzzled look wore away.

"Why," he exclaimed, "you're the boy I saw at the Exposition that Sunday afternoon last June, aren't you?" Then he added, before turning away [Pg 43]to answer a question that a man was asking, "Better buy a Boston Globe in the morning. You'll find a new triumph for the telephone there."

Arthur bought his Globe the next morning before breakfast. Mr. Bell was right. The paper recorded even more successes than the boys had witnessed the night before. Its account of the evening ended with these words:

"This special by telephone to the Globe has been transmitted in the presence of about twenty, who have thus been witnesses to a feat never before attempted: that is, the sending of a newspaper despatch over the space of eighteen miles by the human voice, all this wonder being accomplished in a time not much longer than would be consumed in an ordinary conversation between two people in the same room."

Probably no child who reads this story can remember when the telephone was not so common an object as a lawn mower or an elevator; but those of us who lived through the years when its wonders were slowly developing can never forget our strange, almost uncanny feeling when the voice of a friend who, we knew, was miles away actually came out of a little iron box.

From that day of the Globe report Arthur watched the telephone grow rapidly into public notice. Salem people invited Mr. Bell to repeat his lecture; leading citizens of Boston, Lowell, Providence, [Pg 44]Manchester, and New York within a few weeks clamored for demonstrations in their cities.

By September, 1878, a telephone exchange was set up among the business houses of Boston, with about three hundred subscribers. Two years later the telephone found its way to the little town where Arthur lived, and two instruments were installed—one at the railroad station and another at the lawyer's office.

The next day came the presidential election; and in the evening the lawyer's office was filled with curious men and boys, eager to see whether the telephone would really work or not. Arthur and his father were there, of course. But before any message came, the lawyer had to see a client for a few minutes.

"Here, Arthur, you've used a telephone before. Take my place at the receiver, will you?"

There was no need to ask. Arthur was at the receiver when the lawyer's question was finished. No message came for some time; but at last the bell rang, and Arthur announced proudly:

"He says Florida has gone Republican."

"I knew the thing couldn't be trusted," sputtered an old voter then. "As if the solid South were broken! I'll get my news some other way." And off he went.

"You didn't hear right, I fancy," said the lawyer, returning. "The operator couldn't have said that."

"But he did," insisted Arthur. "I'm sure he did."

"And why not?" quietly asked the school teacher from one corner of the room. "He means the town of Florida, not the state."

"Of course," said everybody.

By 1883, Arthur heard that conversation had been carried on between New York and Chicago, cities one thousand miles apart. "That is all we can hope for," was the general verdict. For a long time it seemed true. But when the country had been covered by a network of wires, there came another long-distance triumph. Communication was open to Omaha, five hundred miles farther west.

And not long ago, Arthur, now a prosperous business man of fifty, a member of the City Club of Boston, sat with several associates around a table at the new club house, each with a telephone in front of him; and over the wires, across three thousand miles of mountain, lake, and prairie, came clearly the voices of the governor of Massachusetts and the mayor of Boston, speaking from the Panama Exposition at San Francisco.

What will be the next triumph of the telephone? To transmit speech around the globe, perhaps. Anyway, here is a newspaper paragraph that asks an interesting question:

"The Mayflower has been called the last frail [Pg 47]link binding the Pilgrims to man and habitable earth. With its departure from Plymouth in America that frail link was severed. The Atlantic cable has surely bound the countries together again. Will the telephone and the aeroplane make the desert of the Pilgrims a popular London suburb?"

"Uncle John, I've decided to go to Wellesley College."

"I'm glad to hear it, Dora. Have you money enough?"

"That's just the trouble, Uncle John. I have exactly twenty-four dollars that I've earned picking berries the last three summers. But I'm only eleven, you know, and I shan't try to go before I'm eighteen. That will give me seven more summers to work. Only I can never pay my college expenses if I can't earn more than eight dollars a summer."

"That's true, Dora. I wish I were rich enough to send you myself. But school teachers are not wealthy, you know."

"Oh, I don't want anybody to give me the money, Uncle John. I want to earn it. Don't you know of something that's more profitable than berry-picking?"

"I'll think about it, Dora."

This conversation took place in 1878, when [Pg 49]Dora's Uncle John, who was a high school principal in New Jersey, was spending his Christmas vacation at Dora's home in a little village on the Maine coast. Nothing more was said about the college money then; but when Uncle John came again in February, he showed that he had interested himself in the ambitious plans of his little niece.

"Dora," he inquired, "do you want to go to college as much as ever?"

"Yes, more, Uncle John. Have you thought of anything for me to do this summer?"

"I know something you can do, Dora, if you want to."

"Oh, Uncle John, what is it?"

"How should you like to work for me?"

"I should like to ever so much. But I don't know enough yet to correct high school papers. All I can do is housework."

"And that's just what I want of you, Dora. You didn't know I had leased the Atlantic House, did you?"

"No, indeed, Uncle John. Do you mean you're coming here summers to manage that hotel?"

"Yes, for the next ten years, anyway, I expect. Do you like to fill lamps and clean chimneys, Dora?"

"Why, that's the part of the housework I can do best."

"That's good. Will you work for me twelve weeks this summer for three dollars and a half a week?"

"Oh, Uncle John, of course I will. But isn't there gas in that hotel?"

"No, just kerosene lamps. I know some people like gas better, but I don't. It's too dangerous and it's bad for one's eyes. So even if I could spare the money this summer, I shouldn't pipe the house for gas. It can't be many years before there will be a cleaner and better light. The Wizard will soon attend to that."

"What do you mean, Uncle? Who is the Wizard?"

"The most wonderful man in America, Dora. His name is Thomas Alva Edison, and he lives in Menlo Park, New Jersey, not far from where I teach. I know him a little. He is the man who, I [Pg 51]think, best represents the scientific spirit of the nineteenth century. He's an inventor, but a systematic one. He doesn't trust to chance."

"What has he invented, Uncle? I don't think I ever heard of him."

"I fancy not, Dora. So far his work has been largely improvements on inventions already made. Just now, as I said, he is experimenting to find a way of lighting buildings by electricity. He will succeed, I know; and I shall wait for his electric light. I expect, though, to wait a number of years yet, for even though he should discover the secret within a few months, no one can supply the necessary apparatus. It will take years, I'm sure, before electric lighting is cheap enough to be common."

"How did you get acquainted with such a wonderful man, Uncle?"

"I knew him first when I was getting ready for college. Like you, I had my own way to pay; and I learned to be a telegraph operator. The summer before I entered Harvard I had a place in the Boston office of the Western Union Telegraph Company. Mr. Edison was a young man too, and he came to work in the office while I was there.

"The night he came we tried to play a joke on him, but the joke was decidedly on ourselves. Edison wore an old linen duster, and looked so [Pg 52]much like a country boy that we thought he couldn't know much about taking messages. So we arranged with a skillful New York operator to send a long message faster and faster, and we saw to it that the new boy had to take it. To our surprise, he proved the fastest operator we had ever known and very carelessly and easily handled the quick dots and dashes. The joke was on the New York operator, too, for after a while Edison signaled, 'Say, young man, why don't you change off and send with your other foot?'

"An operator like that didn't stay long in the office. He went to New York, and almost at once got a position at three hundred dollars a month because he was bright enough to repair a stock-indicator in a broker's office. Soon afterward he improved the indicator so much that the president of the company gave him forty thousand dollars for his new idea.

"Next he proved his value to the telegraph company again by locating a break in the wire between New York and Albany. The president of the Western Union had promised to consider any invention Edison might make if the young man would find the trouble on the line in two days. Edison was not two hours in locating the break; and ever after that the Western Union people were glad enough to be told of all his new ideas."

"Is he working for the Western Union now?"

"No, not now. Just as soon as he had enough money in the bank so that he could afford time to experiment, he opened a factory and laboratory of his own. He made stock tickers for a while; but he cared more about improving them than selling them. 'No matter,' I have heard him say, 'whether I take an egg beater or an electric motor into my hand, I want to improve it. I'm a poor manufacturer, because I can't let well enough alone.' So, instead of making stock indicators, he went to work to improve the telegraph. He saved the Western Union Company millions of dollars by making a device for sending four messages at the same time over one wire. So you see he made their one hundred thousand miles of wire into four hundred thousand without using any more wire. That's a wizard's work, I think."

"I should think so, too," agreed Dora. "That seems to me as hard as singing two notes at once."

"But it can be done, nevertheless; and Edison was so pleased with that invention that he put [Pg 54]his factory at Newark into the hands of a capable superintendent and established a laboratory at Menlo Park, where he is now, about twenty-five miles from Newark. Then he began to think about the telephone. Do you know what that is, Dora?"

"I've heard about it, of course, but I never saw one. There are some telephones in Portland, though."

"Yes, and there's going to be one here. I'm going to connect the hotel with the telegraph office at the station this summer, and sometime I'll give you a chance to talk over the wire. It's easier to use the telephone now than it was at first, for in the beginning there was a continual buzzing that was very annoying; but Edison has stopped all that by improving what we call the transmitter."

Dora's idea of a telephone was indistinct; but she was satisfied with the explanation to come, and she wanted to hear more of Mr. Edison. "Has he made anything else?" she asked.

"Oh, yes," replied Uncle John. "What I think is the most wonderful thing Edison has done is the phonograph. Next to the telephone, that to me is the biggest marvel in the world of science. Think, Dora, of speaking into a machine that makes a picture of the sound waves produced by your voice, and then, a day or a year or a century later, [Pg 55]letting the instrument work backward and hearing your own voice exactly as it sounded at first. Such a mechanism almost frightens me. It makes me sure that if a man like Edison can keep the idle words men speak through centuries, the Master Mind of this universe can keep them for us forever."

Dora must have caught a little of her uncle's thought, for she said, slowly, "Do you mean that everything I say I shall hear again sometime?"

"I don't know exactly, Dora. But I am sure that God, who gave you power to speak, knows how to keep your words forever; and I am sure you will never cease to be glad for all the kind words you may speak for human ears to hear.

"But I'd almost forgotten about the electric [Pg 56]light, Dora. Let me tell you what Edison said about that the last time I saw him. He told me of seeing in Philadelphia what is called an arc lamp—two pieces of carbon that electricity has heated white hot and that give off a powerful light, much more powerful than any gas lamp you ever saw could give. But a lamp like that, though it makes a fine street lamp, is not suitable for lighting a house. It's too bright and too big. Edison says it needs to be subdivided so that it can be distributed to houses just as gas is now.

"That's Edison's present problem, Dora. He is such an untiring worker that I don't believe it will take many months; and when the process is perfected and the implements for generating the electricity can be secured, I mean to make my hotel the prettiest place at night on the Maine coast. But meantime, Dora, suppose you learn to wipe lamps so dry and polish chimneys so bright and trim wicks so even that every summer visitor at the 'Atlantic' will be glad to get away for a while from the flaring, ill-smelling, poisonous gas light."

"I will, Uncle John, I will! I'll be the best lamp-trimmer on the whole Maine coast!"

"That's the spirit that will take you to college, Dora," answered her uncle. "Don't lose a bit of it."

For all the long hot weeks of the next summer Dora worked faithfully every day on the hotel lamps. She had to be at her work at eight o'clock every morning, and she seldom finished before two in the afternoon. But every week her uncle paid her three dollars and a half, and by the end of the season she had forty-two dollars carefully put away. When the hotel closed, her uncle made her a present of eight dollars, so that when she started for school in the fall she rejoiced in the thought of fifty dollars put away in the savings bank as a college fund.

She was happy, too, in the prospect of making as much money the next summer. For the Wizard, Uncle John told her, had not the secret yet. He had succeeded in making a platinum wire, encased in a glass globe, give a light equal to that of twenty-five candles without melting. But he needed to exhaust all the air from the glass globe, and still one one-hundred-thousandth of the original volume remained.

"But that's not sufficient," commented Uncle John. "I know enough about the matter to be sure that so much air as that would prevent the platinum from giving out the light it ought to give. Still, within a short time, Dora, I expect even the [Pg 58]Portland papers will describe Mr. Edison's success with the electric light."

Uncle John's prediction was fulfilled. By the first of October the vacuum was so nearly perfect that only one-millionth part of the original air was left in the glass bulb. By the last of that same month, moreover, the whole secret was practically in Edison's grasp. He had stopped experimenting with platinum for a burner and had gone back to carbon, on which he had pinned his faith at first.

But this time he used the carbon only as a coating for a piece of cotton thread that he had bent into a loop and sealed up in the almost perfect vacuum of glass. When this lamp was connected with the battery, it flashed forth with the brightness that the inventor had so long waited to see. But how long would it burn? There was no sleep for Edison till that question was answered; and it was not answered for forty hours—nearly two days of growing delight and diminishing anxiety.

Such a discovery meant the end of all fruitless experimenting. The secret of the incandescent light was revealed; and the newspapers all over the country—the Daily Eastern Argus of Portland among them—spread the knowledge of the great event in science and prophesied the speedy conquest of kerosene and gas. Late in November Uncle John sent Dora a copy of the Scientific American [Pg 59]which gave the authoritative account of what had been accomplished.

"But," wrote Uncle John in the letter accompanying the paper, "now the real work has only begun. The Wizard knows that some carbonized material is what he needs, but he is sure that carbonized cotton thread is not the best thing. Now he is carbonizing everything he can lay his hands on—straw, tissue paper, soft paper, all kinds of cardboard, all kinds of threads, fish line, threads rubbed with tarred lampblack, [Pg 60]fine threads plaited together in strands, cotton soaked in boiling tar, lamp wick, twine, tar and lampblack mixed, and many other materials that I can't remember. Why," finished Uncle John, "so far he has examined no fewer than six thousand different species of vegetable growth alone. Somebody said something to him the other day about his wonderful genius. 'Well,' modestly answered the great man, mopping his forehead with his handkerchief, 'genius, I think, is one per cent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration.'"

In December there came into Dora's life the most happy and exciting experience of her childhood. The letter from Uncle John in November had ended with this paragraph:

"I am looking forward to my visit to Maine next month, but I'm sorry to say it must be earlier and shorter than usual. I have an important engagement here for the twenty-fourth, and I'm planning to reach Maine on Saturday, the twentieth, spend Sunday with you, and leave there the twenty-second. But I have thought of a way of making my visit last longer and of giving you a new kind of Christmas present. That way is to take you back with me to Jersey and let you see what Christmas and New Year's in the neighborhood of New York are like. If you approve my new idea for Christmas, I want you to let me know at once."

If any twelve-year-old child who lives fifty miles [Pg 61]from a city and has never been farther from home than that city in her life is reading this, she will know how Dora felt at the prospect of such a Christmas journey, and she will understand, too, how Dora had her answer ready for the post office in less than an hour after she had read her letter.

The only event of Dora's wonderful vacation that this story has a right to tell is her visit to Mr. Edison. It happened that in the Herald Uncle John bought as the train was nearing New York, there was a long article describing the lighting system that Mr. Edison had put into successful operation at Menlo Park. "Interest is getting so great in the incandescent light," remarked Uncle John, "that I shouldn't wonder if Mr. Edison let the public see it in operation. If he does, you and I are going to Menlo Park."

The prophecy was a true one. On New Year's Mr. Edison opened his grounds to the public, the railroad ran special trains, and over three thousand people visited Menlo Park. Here is the enthusiastic letter that Dora wrote next day to Maine:

Newark, N. J.

Jan. 1, 1880Dear Father and Mother,

I have been to Fairyland. The enclosed clippings will tell you all about it. I saw the king of the fairies too—I mean Mr. Edison—and he [Pg 62]said, "Good evening, little girl," to me. He talked with Uncle John quite a while, and I heard all they said. Some one asked Mr. Edison when New York would be lighted by electricity and he answered, "I'm working night and day, but you see I have to produce not only a practicable lamp, but a whole system. I haven't found the best material for filaments yet, and there's not a place in the world where I can buy the dynamos (those are machines for making the electricity, Uncle John told me) and the smaller appliances."

Then Uncle John said, "Well, Edison, I'm waiting patiently till you make electric lights cheap enough for me to wire my hotel on the Maine coast. Can you make a prediction?"

"None that's safe," Edison answered. "You know the opposition of the gas companies, and you know the present high cost of the experiments. I've spent already over forty thousand dollars without returns, and my lamps are costing almost two dollars apiece. The public won't take them till they can be sold for forty cents or less. Moreover, I'm not satisfied with my paper carbon lamps. No, there is much work left; but I shall work day and night till New York has a central station and every appliance we need is manufactured at small cost."

"I suppose eating and sleeping don't bother you much just now," some one said.

"Not very much," answered Edison. "I eat when I'm hungry, and I sleep when I have to. Four hours a night are enough, for I can go to [Pg 63]sleep instantly, and I always wake up rested."

Uncle John says that Mr. Edison is the greatest inventor the world has known. Just think of that! And I have seen him!

Yours affectionately,

Dora

Here are two newspaper clippings that Dora enclosed in her letter:

I

A NIGHT WITH EDISON

Menlo Park, N. J.

Dec. 30, 1879

All day long and until late this evening, Menlo Park has been thronged with visitors coming from all directions to see the wonderful "electric light." Nearly every train that stopped brought delegations of sightseers till the depot was overrun and the narrow plank walk leading to the laboratory became alive with people. In the laboratory the throngs practically took possession of everything in their eager curiosity to learn all about the great invention. Four new street lamps were added last night, making six in all, which now give out the horse shoe light in the open air. Their superiority to gas is so apparent, both in steadiness and beauty of illumination, that every one is struck with admiration.

II

The afternoon trains brought some visitors, but in the evening every train set down a couple [Pg 64]of score, at least. The visitors never seemed to tire of lighting the lamps upon the two main tables by simply laying one between the two long wires. Most were content to ejaculate "Wonderful!" But no amount of explanation would persuade one old gentleman that it was not an iron wire that was inside the glass tube. "It could not be the carbon filament of a piece of paper, for," said he, "I have seen some red hot, white hot iron wire, only it was not quite so bright, but it looked just like that. That's no filament!"

"This is a bad time for sceptics," I said to Edison.

"There are some left," he answered. "They die harder than a cat or a snake."

Dora's New York visit colored all the next five years that she worked and waited for college. Her interest in the electric light never wavered for an instant. Like many another, she marveled at the thoroughness of Mr. Edison's search for the right sort of filament and followed expectantly reports of those men whom he sent around the world in search of it.

She read with a bit of almost personal pride the item in the Portland paper that told how, on September 4, 1882, at three o'clock in the afternoon, electric light was supplied for the first time to a number of New York customers; and when, in 1884, that same paper stated that at Brockton, [Pg 65]Massachusetts, the first theater ever lighted by electricity from a central plant had been thrown open, she wrote her uncle:

"I'm sure you'll have to discharge your lamp trimmer pretty soon. But I don't care now, for with father's help, I think I can enter Wellesley in the fall. Of course I hope to work one more summer for you."

Uncle John answered that letter in person, for he needed to go to Maine to make arrangements for the summer.

"I congratulate you, Dora," said he. "You deserve a college course. But I shan't discharge you yet. I expect now to wire the hotel by 1889; but even if I shouldn't need a lamp trimmer all the time till then, I shall always be glad of a capable waitress.—Will you work for me the next three summers?"

"Of course I will, Uncle John," replied Dora as eagerly and gratefully as she had made the same reply six years before. "With the money I can earn the next three summers, I can lessen college expenses a good deal."

So it happened that the ambition of Dora's girlhood; largely through her own pluck and persistence, was realized in due season. Still, she always felt that Mr. Edison unknowingly had a large share in the making of her career; for when in after years [Pg 66]she became an instructor in physics at an influential school, she could easily trace back her love for her subject to her interest in the early experiments upon the electric light.

In March, 1852, Lucy Hobart began a six months' visit with her grandparents who lived just outside Trenton, New Jersey. One morning at the breakfast table, Grandfather Hobart, whom most people called Lawyer Hobart, said to Lucy, "Little girl, a most important case is being tried at the court house this week. It may not be very interesting to a child, but I think that you, as well as Grandmother, ought to attend this morning. I want you to be able to say that you have heard the great Daniel Webster make a plea."

"Do you mean Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, Grandfather?" inquired Lucy. "I thought," she resumed rather timidly, for she feared Grandfather might think she was contradicting him, "I thought people didn't like him any more."

"You come from a strong anti-slavery family, Lucy, the worst kind," answered Grandfather, good-humoredly. "Webster did seem to many people to sacrifice his ideal in that seventh of March speech two years ago, but he's a keen lawyer [Pg 68]yet. His health is broken, though, from the criticism he has suffered. I don't believe he will live much longer. That's why I think you had better go to-day."

"I should like to ever so much," replied Lucy.

"Is it the Goodyear case?" inquired Grandmother.

"Yes," replied Grandfather. "It's his case against Horace Day, who, I think, has been outrageously infringing his patents."

"It's raining a little," remarked Grandmother. "Shall you take us if it keeps on?"

"If you feel like going. If it hadn't been for Mr. Goodyear, you know, you couldn't have gone anyway on such a day," Grandfather added.

"Why couldn't we?" inquired Lucy, after trying to think it out a few seconds.

"My stars! Don't you, a Boston girl, know about Goodyear and his rubber goods?"

"I don't believe so," answered Lucy. "Unless," she added after a pause, "you mean the man that advertises in the Transcript every night. Ever since I could read, I've seen advertisements in the paper about rubber that's been heated to two hundred and eighty degrees."

"Yes, Lucy, that's an advertisement of the Charles Goodyear I mean. I've known him a good many years (he's only a little younger than I, and we were both born in New Haven), and he's had a [Pg 69]hard, sad life so far. To be sure, he's reckoned now as one of New Haven's prosperous business men; but unless he wins this suit, his poverty will come back again. Shall I tell you a little about him so that you'll understand some of the references you'll be sure to hear at the trial?"

"Oh, I wish you would, Grandfather."

Breakfast was over then; and as Grandmother went to the kitchen to give her orders for the day, Grandfather said:

"You and I, Lucy, will sit in front of the fire a little while and talk about Mr. Goodyear. But [Pg 70]first you'd better go with Grandmother and let her give you my galoshes and my rubber cap, and her rubber shoes and your own."

A little girl of to-day, on hearing that request, might not know exactly what she had been sent for. Rubber goods were too expensive then to be common, and "rubber shoes" had not been shortened to our "rubbers." The awkward galoshes was just a name for high rubber shoes, or overshoes.

Lucy came back soon, her arms full. The cap she placed on a table, and the three pairs of rubber shoes she put carefully down to warm in front of the fire.

"It wouldn't have been safe to put my galoshes that I had twenty years ago so near the fire," commented Grandfather, as Lucy drew up her chair beside his. "Can you guess what would have happened to them?"

"Would the fire have burned them, Grandfather?"

"Not exactly, but it would have melted them,—at least have made them as soft as suet. What Goodyear has done is to invent a way of preparing rubber or gum elastic so that it can be used in various thicknesses without being stiff as iron in cold weather or softening like wax with the heat." Then Grandfather interrupted his statements with a question:

"Do you know where we get gum elastic, Lucy?"

"Let's pretend I don't know anything about rubber," answered Lucy judiciously, after a pause. "You begin at the beginning, Grandfather."

Grandfather smiled at the little girl's strategy and began at the beginning.

"Gum elastic is really the dried sap of the South American rubber tree. To get it, the trees are tapped, just as maple trees are tapped here. But the rubber sap is yellowish white and thick as cream. The natives of Brazil long ago discovered that this sap, when hardened, would keep out water. So they made bottles from it and sent the bottles to Europe and the United States. Finally the Portuguese settlers in South America made the hardened sap into shoes; and in 1820 I saw in Boston the first pair of rubber shoes ever brought into the United States. They were as clumsy looking as Chinese shoes. They were gilded, too, not so much to make them beautiful as to keep the rubber from melting."

"Oh, but they must have been handsome," commented Lucy. "They must have looked just like [Pg 72]gold slippers. How much did they cost, Grandfather?"

"I don't know, Lucy. I'm not sure that they were intended to be sold. Two years afterward, though, when there were five hundred pairs for sale in Boston, the price was pretty high. I paid five dollars for mine, I remember. These were not gilded, but they were just as thick and unshapely as the first ones were. They were better than nothing, though, when the weather was not too hot nor too cold.

"During the next few years I suppose there were at least a million pairs of rubber shoes brought into this country and sold for four or five dollars a pair. Then, of course, enterprising New Englanders began to think that if people wanted rubber shoes so much, there would be a good deal of profit in manufacturing them. Then rubber companies prospered for a while; but customers soon found that the rubber shoes they bought were spoiled by heat or cold, and every rubber company went rapidly out of existence.

"It was just about this time that Mr. Goodyear sent for me to come to Philadelphia. He was in the jail there, I'm sorry to say, but for no fault of his, and he needed a lawyer's advice. The hardware firm he belonged to had failed, owing thirty thousand dollars; and though he could in no way be [Pg 73]blamed for the disaster, on account of our poor debtors' laws he had been sent to prison. In spite of his misfortune, he was not downcast. 'It's unfair, Hobart,' he said; 'but there's a way out. Look into this kettle. That's gum elastic I've been melting. The secret of rubber will pay that thirty thousand dollars and give the world the most important commercial product of the century.'

"I was glad he was so cheerful, for I couldn't give him much encouragement about keeping out of prison. Our laws were unfair, just as he said, and I knew that his creditors were likely to send the poor fellow to prison again and again. And so they did for ten long years. But his faith in rubber never wavered. Just after he had been released the first time, I called on him again. 'Here's the means of good fortune, Hobart,' he cried cheerfully; and he showed me a mass of rubber he was pressing into shape with his wife's rolling-pin."

"I'm afraid there was always more rubber than bread under that rolling pin!" commented Grandmother, just then passing through the room on an errand.

"I'm afraid so," agreed Grandfather. "But, Lucy, your grandmother never had much patience with Mr. Goodyear's experiments. I remonstrated a good many times, myself. 'Goodyear,' said I, [Pg 74]when I found him once in a little attic room in New York, boiling his gum with all sorts of chemicals, 'why not give it up? You can't do it without money, and nobody believes in rubber now.'