In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol (etext transcriber's note) |

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol (etext transcriber's note) |

LETTERS FROM THE HOLY LAND

| AGENTS | ||

| America | · | The Macmillan Company 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York |

| Canada | · | The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. 27 Richmond Street West, Toronto. |

| India | · | Macmillan & Company, Ltd. Macmillan Building, Bombay 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta |

BY

ELIZABETH BUTLER

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR BY THE AUTHOR

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1906

Published March 1903

Reprinted July 1906

TO MY MOTHER

CHRISTIANA THOMPSON

THESE letters, written to my mother, and published chiefly at her request, can lay no claim to literary worth; their only possible value lies in their being descriptive of impressions received on the spot of that Land which stands alone in its character upon the map of the world. But the reader will more easily excuse the shortcomings of my pen than, I hope, he will ever do those of my pencil!

I will make no apologies for the sketches, save to remind the reader that most of them had to be done in haste. They are necessarily considerably reduced in size in the reproduction, so as to suit them to the book form.

It was a happy circumstance for me that my husband’s appointment to the Command at Alexandria should have enabled us to realize this journey. A four-weeks’ leave just allowed of our accomplishing the whole tour. The wider round that includes Damascus and Palmyra would, of course, necessitate a much more extended holiday.

The time of year chosen by my husband for our visit was one in which no religious festivals were being celebrated, so that we should be spared the sight of that distressing warring of creeds that one regrets at Jerusalem more than anywhere else. Also the spring season is the healthiest and most agreeable, and we timed our journey so as to begin and end it with the moon which beautified all our nights.

We are chiefly indebted to Mr. Aquilina, the very capable and courteous agent for Messrs. Cook and Son at Alexandria, for the perfect way in which the machinery of the expedition was managed for us. Without such good transport and camps one does not travel as smoothly as we did. To the Archbishop of Alexandria we owe a debt of gratitude for his kind offices in helping to render our way so pleasant.

ELIZABETH BUTLER.

Government House, Devonport,

Christmas Day, 1902.

| 1. | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| 2. | Jaffa | 8 |

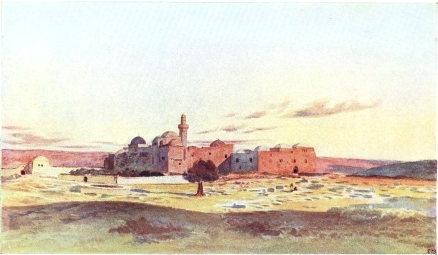

| 3. | The “Cenaculum.” Site of the House of the Last Supper | 26 |

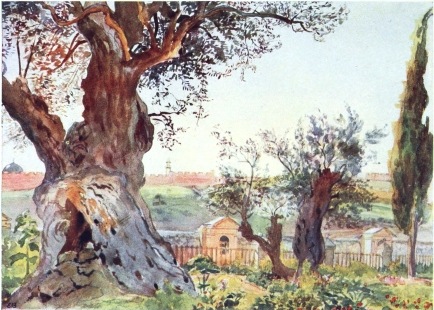

| 4. | In the Garden of Gethsemane. Noonday. Looking towards Valley of Jehoshaphat | 30 |

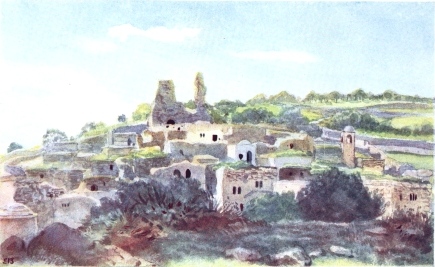

| 5. | Bethany | 32 |

| 6. | “Ain Kareem,” reputed birthplace of John the Baptist, from roof of Convent of the Visitation | 36 |

| 7. | Solomon’s Pools, near Jerusalem, looking towards Dead Sea | 38 |

| 8. | Bethlehem from the Sheepfold, Field of Boaz | 42 |

| 9. | The Plain of the Jordan, looking from “New Jericho” towards Mount Pisgah | 48 |

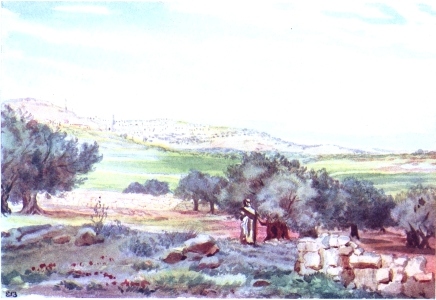

| 10. | The Plain of Esdraelon, from foot of Tabor, with the village of Naim in distance | 60 |

| 11. | Our First Sight of Lake Galilee | 62 |

| 12. | Galilee, looking towards Hermon | 64 |

| 13. | Galilee, looking from near the mouth of the Jordan towards the “Mount of Beatitudes” and Tabor | 66 |

| 14. | Nazareth at Sunrise | 68 |

| 15. | St. Jean d’Acre | 72 |

| 16. | Ruins of the Crusaders’ Banqueting Hall, Athleet | 78 |

The illustrations in this volume have been engraved and printed by the

Carl Hentschel Colourtype Process

In the Adriatic, 28th February 189-.

My....—I am out on the dark waters of the Adriatic. It is late, and the people on board are little by little subsiding into their cabins, and I shall write you my first letter en route for the Holy Land.

If all is well I shall join W. at Alexandria, and we shall have our long-looked-forward-to expedition from thence. Venice has given me a memorable “send-off,” looking her loveliest this radiant day of spring, and were I not going where I am going my thoughts would linger regretfully amongst those lagoons already left so far behind. I watched to the very last the lovely city gradually fading from view in a faint rosy flush, backed by a blue-grey mist, and as we stood out to sea all land had sunk away and the sun set in a crimson cloud, sending a column of gold down to us on the perfectly unruffled waters. Later on the moon, high overhead, shining through the mist, made the sea look like blue air, and quite undistinguishable from the sky. The horizon being lost we seemed to be floating through space, and the only solid things to be seen were the moon and our fellow planets and the stars, so that I felt as though I had passed out of this world altogether. Indeed one does leave the ordinary world when shaping one’s course for Palestine!

Port Said, Sunday, 5th April 189-.

My....—We are moored at Port Said on board the large Messageries steamer, having left Alexandria at 5.30 P.M. yesterday on our way to Jaffa. What a hideous place is this! And this is the Venice that modern commerce has conjured up out of the sea. Truly typical! As I look at the deep ranks of steamers lining the Canal mouth, begrimed with coal-dust and besmirched with brown smoke, I might be at the Liverpool Docks, so much is the light of this Land of Light obscured by their fumes. On the banks are dumped down quantities of tin houses with cast-iron supports to their verandahs. When my mind reverts to the merchant city of the Adriatic and compares it with this flower of modern commerce I don’t feel impressed with, or in the least thankful for, our modern “Progress.” Last night, when we arrived, a barge of Acheron came alongside full of negroes in sooty robes, one gnawing a raw beef bone by the light of the torch in the bows. They were coming to coal us. And, being coaled, we shall draw light out of darkness, loveliness out of hideousness, and this evening we shall be taking our course to the Long-promised Land!

Where shall I finish this? Is it possible that my life-long wish is now so soon to be accomplished?

No two people, I suppose, receive the same impression of the Holy Land. None of the books I have read tally as to the feelings it awakens in travellers. How will it be with me?

Ramleh, on the Plain of Sharon,

6th April.

At sunrise this morning the throbbing of the screw suddenly ceased, and as I went to the port-hole of our cabin I beheld the lovely coast of the Land of Christ, about a mile distant, with the exquisite town of Jaffa, typically Eastern, grouped on a rock by the sea, and appearing above huge, heaving waves, whose grey-blue tones were mixed with rosy reflections from the clouds. Here was no modern harbour with piers and jetties, no modern warehouses, none of the characteristics of a seaport of our time. Jaffa is much as it must have looked to the Crusaders; and we approached it, after leaving the steamer, much as pilgrims must have done in the Middle Ages. The Messageries ship could approach no nearer on account of the rocks, and we had to be rowed ashore in open boats—very large, stout craft, fit to resist the tremendous waves that thunder against the rocky ramparts of Jaffa. How often I have imagined this landing, and have gone through it in delicious anticipation!

Everything was made as pleasant as possible to us, Mr. —— coming on board to direct the proceedings, and a Franciscan monk also boarding the steamer with greetings from Jerusalem, at the request of the Archbishop of Alexandria.

As our boat was the last to leave the steamer I had time to watch the disconcerting process of trans-shipping the other tourists who all went off in the first boats, and nothing I have ever seen of the sort could compare with what I beheld during those breathless moments. The effect produced by brawny Syrian boatmen tussling with elderly British and American females in sun-helmets and blue spectacles, and at the right moment, when the steamer heaved to starboard and met the boat rising on the crest of a particular wave, pushing them by the shoulders from above, and pulling them into the boat from below, was a thing to remember. (To go down the ladder was quite impossible, so violent was the bumping of boat against ship.) To miss the right moment was to have to wait till the steamer which then rolled to port, and the boat which then sank into the trough of the sea, met again with the next lurch. The poor tourists said nothing; they hadn’t time given them for the feeblest protest, but they looked quite dazed when stuck down in their seats. Thanks to our kind friends we had a boat to ourselves and we were not worked off so expeditiously, being thus able to submit with something more approaching grace. We had a large crew of rowers, and being only ourselves, the monk, and Mr. ——, we went light. Three or four times the helmsman had to be extra vigilant as a huge roller, which hid everything behind it, came racing in our wake, and lifting us as though we were so much seaweed, carried us forward with dizzy swiftness. Woe betide that boat which such a wave should strike broadside on! At each crisis the “stroke oar” sang out a warning, and redoubled his work, the perspiration coursing down his face. The whole crew sang an answer to his wild signal in a barbaric minor. Nothing could be more invigorating than this experience; one moment when hoisted on the crest of a wave one saw Jaffa, the Plain of Sharon, and the hills of Judea ahead, and astern the Messageries steamer and small craft riding at anchor, and the next moment nothing between one and the sky but jagged and curling crests of wild billows! On landing at the rocks we were hoisted up slippery steps in more iron grips. On such occasions it is useless to hesitate—indeed they don’t let you—and as you don’t know what is best for you, you had much better at once surrender your individuality and become a passive piece of goods if you don’t want a broken limb.

We immediately found ourselves in such a picturesque crowd as even my Egypt-saturated eyes took new delight in, and we passed through the Custom-house with the agent obligingly clearing all before us, and got into a little carriage after climbing on foot the steep part of the town. What a town! No description I have yet read does full justice to its tumble-down picturesqueness. Those black archways like caverns, those crooked streets filled with people, camels, and donkeys—all this to me is fascinating. I am too hurried to pause here long enough to try and define the difference between life here and life in Egypt. There is not here the barbarism of the latter’s picturesqueness, and one feels here more the beauty of the true East. I don’t see the abject squalor of Egypt, and the people’s dresses are more varied. All this stone masonry is very acceptable after the brick and mud of Egyptian hovels. Here is the essence of Asia—there, of Africa. I am afraid these remarks are crude, but I think the definition is a just one.

As we drove to the little German inn in the outskirts of the town, we noticed the air getting richer with the scent of orange-flowers, and soon we passed into the region of the orange-orchards. The trees were creamy white with dense blossom, and the ripe fruit was dotted about in the masses of white. The honey they gave us at breakfast was from these orange-flowers. Here our dragoman, Isaac, met us. I made my first sketch—the first, I trust, of a series I marked down before leaving Alexandria. It was of Jaffa, seen over the orange-trees from the inn garden, and charming it was to sit there in the cool shade, with birds singing overhead as never one hears them in Egypt. Fragments of classical pillars stood about and served as seats under the chequered shade of flowering fruit-trees along the garden paths. The Mediterranean appeared to my right, and overhead sailed great pearly clouds in the vibrating blue of the fresh spring sky. I must say I felt very happy at the reality of my presence on the soil of Palestine!

At 2 P.M. we started in a carriage like our dear old friend, the “Vetturino,” for Ramleh, our halting-place for the night. How can I put before you the scenes of loveliness we passed through? The country was a vast plain of rolling wheat, bordered in the blue distance with the tender hills of Judea. This land of the Philistines far surpassed my expectations in its extent, its grand sweep of line, its breadth of colour and light and shade. It was some time before we came out on the Plain of Sharon, and we drove first a long way between orange-orchards bordered along the road by gigantic hedges of prickly pear. Our Vetturino was drawn by three horses abreast, all with bells, and it was exhilarating to set out at a fast trot along the easy road in company with other jingling and whip-cracking vehicles, and escorted by horsemen in brilliant Syrian costumes dashing along on their little Arabs, and carrying their long ornamental guns slung across their backs. I had just one horrible glimpse (of which I said nothing, as of some guilty thing), just as we started, of a railway engine under some palm-trees. It is waiting there the completion of the line to Jerusalem to puff and whistle its beauty-marring career to the Holy City. I am thankful my good luck has brought me here just in time to escape the sight of a railway and its attendant eyesores in this sacred land. Why rush through this little country, every yard of which is precious? An express train could run in two hours “from Dan to Beersheba”—and what then?

Before emerging on the Plain we passed a white mosque-like building placed between two cypresses by the roadside, which is supposed to stand on the site of the place where Peter raised Dorcas to life. Be that as it may, the white dome and the black-green cypresses are charming. The soil of the country, now being ploughed in all directions between the green wheat-fields, is of a rich golden colour, like that I noticed with such pleasure around Sienna, and makes a pleasing harmony with the vivid green. The dear olive-tree, beloved of my childhood, is here in its very home. I hailed its pinky-grey foliage and its hoary old gnarled trunk. And now for those wildflowers that all travellers who are so well advised as to come here in spring have told us of. Well may they speak of them with rapture! As we proceeded they increased in variety, and so abundant were they that they made tracts and wide regions of colour over the land. Come here in spring, O traveller! and not in the arid, dusty, burnt-up autumn. On entering the Plain of Sharon we saw to our left the town of Lydda, with St. George’s Church gleaming in the sunshine. Never have I seen, even in Ireland, fresher effects of cloud shadow and sunlight over rolling spaces of waving green corn, and even the sky was typically West of Ireland. Yet lo! in the foreground strings of camels, mules, and wild Bedouins and caracoling Bashi-Bazouks! The ploughing was done by tiny oxen, two abreast, and sometimes a tall camel stalked as leader. On arriving at Ramleh we walked to the great tower, some distance out of the town, from the top of which I had my long-looked-for view of the whole of Philistia—northward to Carmel, westward to the sea, eastward to the mountains of Judah. As the sun sank the tints deepened on that lovely plain, and nothing on earth could be more beautiful than that immense view. I made a hasty water-colour sketch up there, but what can one do in a few minutes with such a scene? A sad spectacle awaited us as we reached the German inn. As we walked I had become absorbed in the contemplation of the limpid sky, where the last lark was carolling to the sinking sun, and of the mountains whose rosy flush was fading into the cool greys that already veiled the plain, when my eyes sinking lower, I beheld in the cold grey of the narrow street, ranged along a stone wall, a row of lepers waiting for alms. Life has no sadder detail than the leper. As I approached them with a coin the nearest of these poor creatures put out a fingerless palm on which I placed the money, and having only hollow sockets in the place of eyes it handed it to its neighbour, who, being also eyeless, passed it on to one in whose fleshless face there lingered the remnant of an eye. This one’s hand lifted the coin to its fragment of eye to see its value, and deposited it in the recesses of its fluttering rags that only half veiled the decaying body. A low wail passed along the line, and bony arms were stretched out in gratitude. And then we go to our table d’hôte and comfortable beds, and they—where do they sleep? Do they lie down on those bare bones?

Jerusalem, 7th April 189-.

My....—We left Ramleh early this brisk, fresh morning, the air full of scent from the wildflowers. Frère Benoît, the Flemish Franciscan who met us on board the steamer, came with us, and an English lady who had all but broken down the day before through the jolting of a shandrydan that had been palmed off on her and her husband at Jaffa. So with the friar and Mrs. G—— inside, W. on the box, and Mr. G—— following in the aforesaid shandrydan with Isaac, we set off in the usual whip-cracking, shouting, and prancing manner for

JERUSALEM!

The first point of interest I was looking for was Ajalon. As we dipped down from one of the hills traversed by the road in steep zigzags it unfolded its fresh loveliness on our left, but we could not see the actual site of Joshua’s battle, as it was too deep in the folds of the hills. This view was, perhaps, the loveliest of all, and nothing could be fresher than those cornfields and rich spaces of ploughed earth in the light that streamed down from so pure a sky. Now and then a single horseman with the well-known long gun inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and with his Arab all over tassels, dashed past us, doing “fantasia” to impress us strangers. The proceeding was never without success as far as I was concerned.

At 9.30 we left the plain and at once entered the hills of Judea, which are much more uniformly stony than one would suppose them to be from a distance. We soon stopped at a wayside khan, about half-a-dozen Vetturinos being assembled in the yard, and all the horses were rested. We then began the ascent of the dear Hill Country, fragrant with memories of Mary on her journey made in haste from Nazareth. I did not expect such a long and high ascent, having failed to realise from description the immense altitude of the height of land that holds Jerusalem. “Things seen are mightier than things heard.” The wildflowers increased in beauty and variety, chief, I think, amongst them being the crimson anemones with black centre which tossed their gay heads everywhere in the mountain breeze. Olives and stones, stones and olives on all sides. Here and there a carob tree or a clump of tamarisk at a tomb. As we crested the first pass and looked back we saw the plains of Philistia, with Ramleh white in the sunshine and the sea beyond shining in a long flash of silver. Before us to the right soon loomed against the clouds the great tombs of the Maccabees, and away to our left on a high cone appeared, remote and awful, the “Tomb of Samuel,” a dominating feature over all the land.

As we descended on the other side of the pass we came in sight of Ain Kareem, the reputed birthplace of John the Baptist, on the side of a high hill. The words of the Magnificat sounded in one’s mind’s ear. It is a grand situation and most striking as seen from the road. At the bottom of the valley formed by the hill we were descending and the hill of Ain Kareem runs the dry bed of the brook from which David chose his smooth stone for Goliath. W. went down and selected just such a smooth white stone as a memento. At the bottom of the valley we halted at a Russian khan and I took a little sketch of a bit of hillside and a pear-tree in blossom. You must have seen this land with “second sight,” for you have always seen a flowering fruit-tree in your mental pictures of it at Eastertide and Lady Day. Palestine is essentially the land of little fruit-trees.

On leaving the Russian khan, where we beheld chromo-lithographs of the late and the present Czars on the walls, and were interested in the high Muscovite boots of our host, we had another great ascent, and soon after reaching the top my feelings became more and more focussed on the look-out ahead. I saw signs that we were approaching Jerusalem. There were more people on the road, and a detachment of the Salvation Army was marching along with a strangely incongruous appearance. Yet only incongruous on account of the dress, for, morally, those earnest souls are amongst the fittest to be here. I stood up in the carriage, but W. from the box saw first. He raised his hat, and a second after I had the indescribable sensation of seeing the top of the Mount of Olives, and then the Walls of Zion! It was about three o’clock.

We left the carriage outside the Jaffa Gate, for no wheeled vehicle can traverse the streets of Jerusalem, and we passed in on foot.

We had first to go to the hotel, of course, a very clean little place facing the Tower of David. Thence we soon set out to begin our wonderful experiences.

I had what I can only describe as a qualm when we reached, in but a few hundred steps, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It was all too easy and too quick. You can imagine the sense of reluctance to enter there without more recollection. I had a feeling of regret that we had not waited till the morrow, and I would warn others not to go on the day of arrival. We reached the Church through stone lanes of indescribable picturesqueness, teeming with the life of the East, and there I saw the Jerusalem Jews I had so often read of—extraordinary figures in long coats and round hats, a ringlet falling in front of each ear, while the rest of the head is shaved. They looked white and unhealthy, many of them red-eyed and all more or less bent, even the youths. No greater contrast could be seen than between those poor creatures and the Arabs who jostle them in these crowded alleys, and who are such upstanding athletic men, with clear brown skins, clean-cut features, and heads turbaned majestically. They stride along with a spring in every step. There are Greeks here, and Russians in crowds, and Kurds, Armenians, and Kopts—in fact samples of all the dwellers of the Near East, wearing their national dresses; and through this fascinating assemblage of types and costumes, most distracting to my thoughts, we threaded our way to-day, ascending and descending the lanes and bazaars, up and down wide shallow steps, till we came in front of the rich portal of the Church of churches. With our eyes dazzled with all that colour, and with the sudden brilliance of the sunshine which flooded the open space in front of the façade, we passed in! Do not imagine that the church stands imposingly on an eminence, and that its proportions can strike the beholder. You go downhill to it from the street, and it is crowded on all sides but the front by other buildings. But its gloomy antiquity and formlessness are the very things that strike one with convincing force, for one sees at once that the church is there for the sake of the sites it encloses, and that, therefore, it cannot have any architectural symmetry or plan whatever, and its enormous extent is necessitated by its enclosing the chapels over Calvary and the Holy Sepulchre and many others besides, which the Empress Helena erected over each sacred spot whose identity she ascertained with so much diligence. It is very natural to wish that Calvary was in the open air,—lonely, under the sky that saw Christ suffer on the Cross. But already, in the year 326, St. Helena found the place of execution buried under mounds of rubbish purposely thrown upon it; and where would any trace of it be to-day had she not enclosed it—what with man’s destroying acts and the violence of the storms that have beaten against this rock for nineteen centuries and more? It was, to begin with, but a small eminence close outside the walls. On entering the church you discern in the depths of the gloom of the tortuous interior the rough steep steps cut in the rock that lead to Calvary, on your right hand. On climbing to the top, groping in the twilight, you find yourself in a chapel lined with plates of gold and hung with votive lamps. The sacred floor, which is the very top of Calvary, is entirely cased in gold, and under the Greek altar is shown the socket of the Cross, a hole in the rock. Our altar stands to the proper left of the Greek, which has the post of honour. Descending from Calvary there is a long stretch of twilight church to traverse before we come to the sepulchre. Again I had not realised, from the books I have read, the great distance that separates the two, and, indeed, many writers in their scepticism have done their best to belittle the whole thing. I confess that before to-day I was much under the influence of these writers, but I have now seen for myself, a privilege I am deeply thankful for. It was an overwhelming sensation to find the spaces that separate the sites so much vaster than I had expected, and to have, at every step, the conviction driven home that after all the modern wrangling and disputing the old tradition stands immovable. It certainly would be hard to believe that when St. Helena came here the dwellers of Jerusalem should have lost all knowledge of where their “Tower-hill” stood in the course of three centuries. She was commissioned, as you know, by her son the Emperor Constantine, that ardent convert to Christianity, to seek and secure with the utmost perseverance and care all the holy sites, and to her untiring labours we owe their identification to this day. The great central dome of the church rises above the chapel of the Holy Sepulchre, which chapel stands in the vast central space, a casket enclosing the rock hollowed out into Our Lord’s Tomb and its ante-chamber. You enter this ante-chamber and, stooping down, you pass on your hands and knees into the sepulchre itself. On your right is the little low, rough-hewn tomb, covered with a slab of stone worn into hollows by the lips of countless pilgrims throughout the long ages of our era. A monk keeps watch there, and beside him there is only space enough for one person at a time. I have made many attempts to tell you my thoughts and feelings during those bewildering moments of my first visit, but I find it is impossible, and you can understand why.

Jerusalem, 8th April 189-.

My....—To-day was exquisitely bright and full of heart-stirring sights to us. Those who have not been here can scarcely, I think, realise the sensation of living in daily intimacy with the scenes of Our Lord’s Passion. Think of lying down at night under the shadow of the Cross. To-day we first visited the Wailing Place of the Jews. Strange and pathetic sight, these weird men and women and children weeping and moaning, with their faces against the gigantic stones of the wall that forms the only remaining portion of the foundation of their vanished Temple, praying Jehovah for its restoration to Israel; and over their heads rises in its strong beauty the Moslem Mosque of Omar, standing in the place of the “Holy of Holies,” the varnished tiles of its dome ablaze with green and blue in the resplendent sun! Jews below, Moslems above, yet to the Christian, Christ everywhere!

Then we followed the “Via Dolorosa,” which winds through the dense town, starting from the Turkish barracks on the site of Pilate’s house. Of course, I need not say that the surface of Jerusalem being sixty to eighty feet higher than it was in Our Lord’s time, the real Via Dolorosa is buried far below, but the general direction may be the true one. Strange to see the Stations of the Cross appearing at intervals on the walls of alleys crowded with Jews and Mahometans. There are no evidences of Turkish intolerance in Palestine that I can see! The last stations are, of course, in the great Church. We followed the walls from Mount Moriah to Zion and round by Accra to the Damascus Gate, outside which stands General Gordon’s “Skull Hill,” which he so tenaciously clung to as the real Calvary (on account of its resemblance to a gigantic skull), together with the sepulchre in a garden at the foot of the mound, which he held was that of Joseph of Arimathea. As far as my eye can tell, the distance between “Skull Hill” and this sepulchre is much the same as between Calvary and the sepulchre that tradition hallows. I send you a sketch that I made on the spot of Gordon’s “sepulchre,” to show you the universal plan of these burial-places. You will see three tombs (their lids are gone) in the inner chamber. At the Holy Sepulchre only Our Lord’s is preserved, tallying with the one I have marked with a cross; the other two have been cut away.

I made a very hurried sketch of Jerusalem, with the Mount of Olives and a glimpse of the mountains of Moab, from the hotel roof. Had I been perched a little higher I could have shown the head of the Dead Sea. We visited the Mosque of Omar, one of the great sights of the world. The immense plateau on which the Temple stood is partly occupied by this, the second oldest of mosques, and by great open spaces planted with gigantic and ancient cypresses and by a smaller mosque. The whole group is surpassingly beautiful, but what thoughts rush into one’s mind in this place! A vision of Herod’s Temple fills the whole space for a few moments with its white and golden splendour, its forest of shining pinnacles flashing in the sun, and its tiers of pillared courts culminating in the Holy of Holies. And then the reality lies before us again—great empty spaces and two pagan mosques. From thence we went out by St. Stephen’s Gate, and looked down on Gethsemane on the opposite side of the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Very dusty and stony looked that part of the Mount of Olives, and the excavations for the building of numerous churches by various sects have greatly spoilt its repose and beauty and disturbed its seclusion. But one must not complain. All Christians naturally long to have a place of worship there.

I cannot describe to you the charm of life here. All one’s time is filled to overflowing with what I may call the “holy fascination” of the place, and though all this continual walking and standing about may be somewhat fatiguing in a physical sense, the mind never is weary and the fatigue is pleasant. At night, sound sleep, born of profound contentment at the day’s doings, so full of keen interest without excitement, renews one’s vitality for the succeeding day’s enjoyment.

9th April 189-.

This has been a day of clear loveliness, much hotter and altogether exquisite. In the morning we first went to the “Cenaculum,” the rambling building erected over the site of the house of the Last Supper, which St. Helena found and enclosed in a chapel, and also including the undoubted Tomb of David, jealously guarded from us by the Mahometans. The Cenaculum stands out lonely and impressive, looking towards the mountains of Moab and the dim regions to the south of the Dead Sea. I will show you a sunset sketch of this.

I was not pleased to feel hurried through those rooms and narrow passages and stairs by the guide in a rather nervous manner, when I perceived that the reason was the unfriendly looks of the Mahometans who moved about us, and who evidently resent the presence of Christians so near the royal tomb. I was too much distracted to realise where I was, and indeed, not till we get away from the noise and bustle of town life into the solitudes shall we be able to fix our thoughts as we would wish.

From the Cenaculum we walked half-way down to the valley through which the brook Cedron flows, and by very much the same path that Our Lord must have followed to go to Gethsemane after the Last Supper. Down to our right was the desolate Gehenna—the Pit of Tophet—now only inhabited by lepers, and a ghastly hollow it looked. Beyond rose that hill where once sat Moloch of the red-hot hands, and deep down on the declivity between us and these landmarks of terror lay the Potter’s Field. When looking from some commanding height

over the city and its surroundings the mind staggers at the thought of the appalling catastrophes that have burst upon this narrow area—the human agony that has been concentrated here through so many ages, of which we read in the Old Testament and in the writings of the early historians of our era. Twenty-five fierce sieges has this mountain fastness endured. No other city ever went through such sufferings. If we could really concentrate our thoughts upon the events that have passed upon this ground which, from such a standpoint as ours of this morning, the sight can compass in one sweep of vision, it would be too painful to be endured. Perhaps if I could see the place on some bleak twilight or in a sounding thunderstorm I might dimly appreciate the long agony of Jerusalem, but to-day the April air was full of scents of flowers and aromatic shrubs, and the bees were humming; there were little butterflies amongst the anemones, and the lark was in full song. The very spirit of the Gospel peace seemed to float in the gentle air of spring. I was glad I could not concentrate my thoughts on the gloomy side of that wondrous prospect.

From the cave whither St. Peter crept away to weep after the denial of Our Lord is certainly the finest view of the site of the Temple to be obtained anywhere. This cave is some distance down the path from the Cenaculum and the house of Caiaphas, which latter we had also visited, now a beautiful chapel.

In the afternoon we had our first ride, and went by the old stony track so often trodden by the Saviour to Bethany. Never shall I forget the view of the Dead Sea, Jordan, and mountains of Moab which burst upon us as we crested the summit of the Mount of Olives and passed by the traditional site of the Ascension. The ride down to Bethany, on the reverse slope of the Mount, was enchanting, and how solemn all was to us—the deep black “tomb of Lazarus,” the site of the house (now a ruined chapel) where Jesus so often stayed. We returned by the lower, or new, road from Jericho, and had at sunset that grand view of Jerusalem from the lower slopes of Olivet which has so often been painted. We reserved Gethsemane for another time, but visited the ancient Church of the Assumption on our way home.

Jerusalem, 10th April.

My....—We spent the whole morning in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, I remaining alone for an hour after W. left to write letters at the hotel. There was hardly another soul in that vast building, except a few priests and the monk who keeps watch over the Tomb. I find I can write least about this, the climax of what makes Palestine the Holy Land.

At two o’clock I went to Gethsemane, escorted by Isaac, where I sketched till six. I would have preferred a moonlight sketch of that garden, but I had to be content with a very hot daylight one. It was blissful sitting there undisturbed under the old olives whose trunks are as hard as stone, and I pleased myself with the idea that they might be offshoots of offshoots of the trees that shaded Our Lord. When Titus had all the trees around Jerusalem cut down, some saplings may have been overlooked! My protecting dragoman was somewhere out of sight, and the Franciscan monks who own this most sacred “God’s Acre” were unobtrusively tending the flowers somewhere about. Insects hummed amid the flowers, all the little burrings of a hot day were in the air, it was a place of profound peace. As I returned, towards sunset, and climbed the steep sides of the Valley of Jehoshaphat up to St. Stephen’s Gate—the shortest way to the City—I looked back towards the scene of my happy labours, and a sight lay there below me which impressed me, I am sure, for life. The western sides of the abyss which I was climbing were already in the shades of night, for twilight hardly exists here, but the opposite slopes received the red sunset light in its fullest force, and in that scarlet gleam shone out in intense relief thousands upon thousands of flat tombstones that cover the bones of countless Jews who have, at their devout request, been buried there to await, on the spot, the Last Judgment which they and we and the Mahometans all believe will take place in that valley. Had I more time I would much like to make a study of this truly awful place in that last ray of the vanishing sun, for nothing could be more impressive and more touching, but higher-standing subjects claim all the time I can spare. My intention is to use all my sketching moments for scenes connected with Our Lord’s revealed life. I resolutely deny

myself the indulgence of elaborately sketching the people and animals that seem to call out to the artist at every turn, though I have outlined some in my note-book. Anywhere else our fellow-travellers at the hotel would be too tempting in my lighter moments, so comical they look in their sun-proof costumes. Why such preparations against the April sun? But one is too “detached” here to be much distracted by their unspeakable outlines. And, talking of distractions, I really do not find the drawbacks of Jerusalem, which so many travellers give prominence to in accounts of their experiences, so very bad. Indeed our life here is without a single drawback, to my thinking.

Saturday, 11th April 189-.

The heat is greatly increasing. At 1.30 we drove to Bethlehem with our friend, Frère Benoît. The hill country we passed through was very stony and rocky, and only cultivated here and there. Again olives and stones, stones and olives everywhere. The inhabitants are a splendid race, the men athletic, the women graceful, though their faces are sadly disfigured by tattooing. We were on the look-out for the little city of David long before it appeared, and very beautiful it looked as we beheld it from a high hill, crowning a slightly lower one amid a billowing sea of other hill-tops. It has a majestic appearance on its rocky throne, and its large, massive conventual buildings add greatly to its stateliness. We passed that pathetic monument, Rachel’s Tomb, at the cross roads, our road leading to the left, and the other diving down to the right towards Hebron. We ascended Bethlehem’s hill and were soon in its steep, narrow, slippery stone lanes, utterly unfitted for a carriage. We drove at once to the Franciscan Convent and then to the Church built over the site of the Nativity, and had the happiness of kneeling at the sacred spot where the manger stood, which is shown in the rocky vaults below, and marked with a white star inlaid in the floor. The cave was rich and lovely with votive lamps and gold and silver gifts. Little by little the dislike I had to the too precise localisation of the events we love most in the Bible is disappearing. Speaking for myself, I find that, on the spot, the mind demands it. But I know that many people regret it. I only wish that, in their separate and individual ways, all

who come here may feel the happiness that I do.

In a very dark niche in the rocks close to where the white star shone out in the floor I perceived the figure of a Turkish sentry, breech-loading rifle and all, standing on his little wooden stool, motionless. Well, do you know, though my eyes saw him my mind was not thereby disturbed any more than it was by the Turkish guard at the door of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. I could not bring my thoughts down to that figure and the reason of its being there.

We visited St. Jerome’s Cave, close by, where he worked, near the scene of his Redeemer’s birth, giving to the world the translation into the Vulgate of the Holy Scriptures. Then we walked down to the field of Boaz, full of waving green wheat, in the midst of which stands the sheepfold surrounded by a stone wall. You must imagine the shepherds looking up to Bethlehem from there on that Christmas eve. The little city is seen from the sheepfold high up against the sky to the west about two miles off. I had only time for a pencil outline of this view, hoping to colour it on a future occasion. All the country round was very pastoral, and just such a one as one would expect. Wildflowers in great quantities, and larks—little tame things with crests on their heads—enjoying the sun and the breeze, quite unmolested; lovely sweeps of corn in the valleys, olive-clad or quite grassless hills bounding the horizon all round—can you see it? How many figures of Our Lady we saw about the fields and lanes with babes in their arms! Surely the old masters got their facts about the drapery of their Madonnas from here, where all the women wear blue and red robes, exactly as the Italian painters have them.

Sunday, 12th April.

We went to seven o’clock mass at the Latin Altar on Calvary. We were in a dense knot of people, who were kneeling on the floor in that dark, low-roofed chapel, lit by the soft light of lamps hanging before each shrine. How often we say in our prayers, “Here, at the foot of Thy Cross.” We were literally there. After breakfast with the prior at the Casa Nova Monastery, which used to be the hostelry for travellers before the hotel was in existence, we drove with Frère Benoît to the reputed birthplace of John the Baptist, Ain Kareem in the Judean Hills. I believe there is considerable doubt as to this site, but there is the possibility. It was a very poetical landscape that we passed through, and there were many flowering apricot, pear, and almond trees as we neared St. Elizabeth’s mountain home. We first visited the site of the Baptist’s birth high up in the north end of the village, now covered by a church, and then we crossed over to the south side of the valley to St. Elizabeth’s country house, also now a chapel, where her cousin visited her. There is a deep well of most cool crystal water at the side of the altar in this “Chapel of the Visitation,” which belongs to the Spanish monks. From the roof of the convent over this chapel I made a sketch of the little town on its hillside planted with cypress trees. The heat here in this enclosed valley was very great.

Monday, 13th April.

We were up at five for our drive to Hebron. I longed to see this most ancient city and that mosque which, without any doubt whatever, covers the “double Cave of Machpelah” which Abraham bought for his own and his descendants’ burying-place. “There,” said Jacob when dying, “they buried Abraham and Sarah his wife; there they buried Isaac and Rebekah his wife; and there I buried Leah,” and there also they buried Jacob. Think of it! If we could look into those tombs and see the very bones of Abraham and Isaac and the mummy of Jacob, for the Bible tells us he was embalmed according to the manner of the Egyptians. Altogether, though, our visit to Hebron has rather given me the horrors. Near Rachel’s tomb we left the Bethlehem road and dived down to the “Vale of Hebron,” the heat increasing greatly as we descended. We halted for the mid-day refection (how more than usually horrid the word “lunch” sounds here!) and rested in the “shadow of a rock in a thirsty land,” where tradition says Philip met the Eunuch journeying from far-off Meroe on the Upper Nile. It was a wilderness of stones, where the big lizards of Palestine were in strong force, panting over the top of every rock, their black heads and goggle eyes upturned to the burning sky in a very comical way. Close to Hebron is a nice cool German hostelry, where we rested before descending to the gloomiest town I have ever seen in the East, with

some of its bazaars like tunnels, into which scarcely any light could enter. Here in the gloom we met insolent-looking Moslems and spectral Jews, their strongly-contrasted figures and faces appearing for a moment in the twilight as they passed us. And outside it was blinding noontide sunlight. We went all round the huge mosque that guards the precious tombs of the patriarchs, but had we attempted to enter we should have had a bad quarter of an hour from the Mahometans. These sons of the Bondwoman would stone any son of the Free who would attempt an entry. There is a little black hole in the wall, which I am sure does not pierce it through, which we are told we can look through and see the tombs from outside, but I saw nothing in the hole but the beady eye of a lizard. We do not feel as though we would care to revisit Hebron.

We drove back to the German khan which was full of exhausted Americans who had also returned from the oven of Hebron. Most of them had been trying to combine botany with Biblical research, and near many of the figures that lay prone on the divans I saw Bibles and limp flora on the floor.

Towards evening we drove from this place of rest a long way back on the road to Jerusalem, but not far short of Bethlehem we came in sight of our camp! How charming and inspiriting that sight was—three snowy tents pitched by the Pools of Solomon under the walls of a Crusader Castle, with some fifteen saddle and baggage animals picketed close by, and the dear old Union Jack flying from the central tent! I was delighted at the fact that our camp life was to begin that night. Everything struck us as in excellent order, our horses, saddles and bridles, the tents, the servants and all. Those Pools of Solomon are three immense reservoirs of water which the Wise King made to supply the Temple at Jerusalem. Myriads of frogs were enlivening the evening air with their multitudinous croakings which increased to deafening proportions as night closed in. I took a hasty sketch. Much hyssop grows here, “Asperges me, Domine, hyssopo et mundabor.”

14th April.

I was greatly pleased with my first night under canvas. To have grass and stones and little aromatic herbs for a bedroom carpet was a

new and delightful sensation to me. We started this morning at sunrise, my sketching things handily strapped to my saddle by W.’s directions, in a flat straw aumonière. Isaac had swathed his tarboush in a magnificent “cufia,” and our retinue wore the baggy garb of Syria. W. rode a steel-grey Arab, I a silver-grey, Isaac a roan-grey, and the man, whom we call the “flying column,” because he is to accompany us with the lunch bags, while the heavy column with baggage, tents, etc., goes on ahead by short-cuts, rode a chestnut. We passed through Bethlehem and down to the Field of the Shepherds, where I completed, as well as I could in the heat and glare, my sketch begun the other day. A group of some twenty Russian pilgrims arrived as we did, and we saw them in the grotto of the sheepfold, each holding a lighted taper and responding to the chant of their old priest, who had a head which would do admirably for a picture of Abraham. These poor men were in fur coats and high clumsy boots, and one told us he had come from Tobolsk, and had been two years on that tramp. He assured us he could manage his return journey in no time, only ten months or so. Their devotion was profound, as it always is, and was utterly un-self-conscious. I think we English are too apt to suppose that because devotion is demonstrative it is not deep. Great pedestrians as we are, how many Englishmen would walk for two years to visit this sheepfold? That two years’ test borne by the Russian peasant must have gone very deep.

I remember reading with much approval, when a child, with a child’s narrow-mindedness, Miss Martineau’s shocked description of the demonstrative piety of a noble Russian lady on Calvary, who repeatedly laid her head in the hole where the Cross had been, weeping and praying and behaving altogether in a most un-English manner. The memory of that passage came back to me to-day as I saw these rough peasants, so supremely unconscious of our presence, throwing themselves heart and soul into their adoration of God, and I thought of Mary Magdalene and her prostrations and tears.

After the service for the Russian pilgrims “father Abraham” fell asleep under an olive-tree, with his hoary head on a stone which he had cushioned with dock leaves, and the younger priest who had taken part in the service went back to his ploughing, which he had left on the approach of the pilgrims. They both had their Fellaheen clothes under their cassocks, and they wore the tall Greek sacerdotal cap. They were natives of Bethlehem. “Abraham” blessed our meal, but refused to partake of it, except the fruit, as this is the Greek Lent. We had a long talk with him through Isaac, and a lively theological argument, which had the usual success of such undertakings, enhanced by its filtration through a Mahometan interpreter converted to Protestantism by the American Baptist Mission at Jaffa. That old patriarch was a magnificent study as he sat, pointing heavenwards under the olive-trees and discoursing of his Faith, with Bethlehem rising in the distance behind his most venerable head. He made some coffee for us, a return civility for the fruit, and as we rode off many were the parting salutations between us and the group of people who had been the audience of our theological arguments, made unintelligible by Isaac. Among the crowd was an ex-Papal Zouave who turned out to have been orderly to a friend of ours in the old days at Rome.

We rode along a track in the field of Boaz, now knee-deep in corn, a cavalry soldier, who had been sent to escort us through the “dangerous” region, leading the way. His escorting seems to consist of periodical “fantasia” manœuvres, when he shakes his horse out at full gallop, picking a flower in mid-career and circling back to present it to me,—a picturesque proceeding in that floating caftan and white and brown striped burnous. I am pleased to see this figure in our foreground caracoling, curveting, and careering. He is in such pleasing harmony with his native landscape. He and Isaac are all over pistols and weapons of various sorts, but W. says that the necessity for arms in Palestine is now a thing of the past, and only a bogey.

Our course lay south-east, as we wished to visit the far-famed Greek monastery of Mar Saba on our way to our camp. Formerly there was great danger and difficulty in going to this extraordinary place, owing to the fierce robber Bedouins that haunted these regions, and in many accounts of Palestine travel I have read of the disappointment of the writers at the impossibility of making this visit. It is an awe-inspiring place. The

monks have even denied themselves that great earthly consolation of natural beauty which our monasteries, as a rule, are so well situated to enjoy. On the edge of an abyss of rock, through which the now dry Cedron once rushed to the Dead Sea, and facing the opposite rock pierced with the caves of former hermits, it is so placed as to have not one beautiful thing within sight, and as little of even the light of the sky above to give a ray of cheerfulness. We saw pigeons and paddy birds arriving in flocks to the rock ledges, and had glimpses of furtive furry things coming round corners. We marvelled at the presence of the paddy birds so far from water till we were told the pleasing fact that all these wild things since time immemorial have been in the habit of congregating here to the sound of the bugle, to be fed by those Greek monks. They were waiting for their dinner-bell!

I soon had enough of Mar Saba, but W. thought a month there with two camel-loads of books would be very pleasant. We espied our camp after leaving this dread place a long way below us in a hot hole, amongst most desolate mountains, whose cinder-coloured sides neither distance nor atmosphere could turn purple, and some of these were pale yellow, spotted at the top and half-way down with black shrubs, conveying an irresistible impression of mountains covered with titanic leopard-skins. The deadness of the Dead Sea was beginning to be felt.

A great wind arose in the night, and had not W. seen himself to the tent ropes and pegs our tent would certainly have been blown down, and we should have been smothered in a mass of flapping canvas. As it was, the tent shook and heaved at its moorings and cracked like pistol-shots, some of the furniture coming down with a crash. All night the pistol-shots, the flappings, and the creakings went on, so that I was rather disconcerted at losing my night’s rest, for the morrow was, as W. said, to be my “test day.” If I stood it well—it being the hardest we should have—I would do the journey.

Wednesday, 15th April 189-.

We were off at sunrise on a tremendous ride, down to the Dead Sea, up the Jordan and round to Jericho—about eight hours in the saddle, exclusive of dismounted halts. We were very fortunate, for the wind which had so troubled our slumbers kept away the heat, which in these regions is most trying. We descended to 1300 feet below the level of the Mediterranean, and not a tree was to be seen till we gained the green banks of Jordan, where we made our halt after half an hour’s rest on the beach of the Dead Sea. All my expectations of the desolation of “Lake Asphaltites” were fulfilled, but the bitter burning of its salt far surpassed what I expected. I could realise how Lot’s wife, lingering in her flight from the doomed Sodom to look back till the fringe of the destruction that engulfed the Cities of the Plain covered her, remained stiffened into the semblance of a pillar of salt (“statue” of salt in our version) when my hand in drying, after I had but dipped it into the crystal-clear water that now fills the hollow delved by the swirl of the great cataclysm, was stiff and white with the plaster-like brine. The wan look of the blue shrubs that grow here was like something in a dream, and the air was full of huge locusts, brilliant yellow, tossed by a high hot wind. The earth was cracked by the heat into deep chasms, and the treeless mountains round the sea were lost at its farther end in a mist of hot air. There was great beauty with this desolation, but the mind felt oppressed as well as the body. The blue of the sea was exquisitely delicate, and gave no idea in its soft beauty of the fierce bitterness of its waters. I felt deep emotion on sighting Jordan’s swift-rolling stream—a touching and unspeakably dear river—but beautiful only for its holiness, for the water is thick with grey mud, and the banks are tangled with the shaggy débris that the over-hanging trees have caught as the winter flood brought them swirling down. The heat there was great, and the flies made it absolutely impossible to take a sketch of the place tradition says saw the baptism of Our Lord. I was much disappointed, for the flies fairly drove us away, and in the burning heat we turned our horses’ heads towards Jericho, unable to bear these tormentors any longer. We were to camp at “new Jericho”—a huddled group of mud-pie houses situated in a garden of lovely trees and shrubs and flowers, which, owing to the abundance of water flowing through this region, grow in tropical luxuriance. In the far western distance, above all the mountain-tops intervening, we kept the Mount of Olives in view, with that tall landmark on the top, the tower of the Russian “Church of the Ascension,” and only lost it as we neared our camping-place. Before us, to our right, a beautiful mountain of more stately lines than those of the weird crags around it rose solemnly against the west—it was the Mountain of Temptation, where Our Lord was tempted after His forty days’ fast. Immediately on reaching our camp I made a sketch of the plain, looking towards Mount Pisgah in the land of Moab to the east. I was just in time to save the sunset. Would that we could include Pisgah in our pilgrimage, and receive on our retinæ the same image of the Promised Land that Moses received on his!

In spite of the baying of dogs, the braying of donkeys, and other camp noises sleep came swiftly and soundly that night.

Thursday, 16th April.

We set out at six for Jerusalem, the sun rising over the mountains of Moab. We passed over the site of “old Jericho,” and saw what a magnificent site they chose for it, backed by mountains in a majestic semicircle, and looking on the Plain of the Jordan.

The Bible speaks of a “rose plant in Jericho” as of something superlatively lovely amongst roses, and one may ask why particularly in Jericho? Here one can answer the question, for one sees how richly the flowers grow in this land of many streams, which is all the more conspicuous for its exuberance as contrasted with the aridity of the surrounding regions. I can best describe the fascinating quality of our journey by saying that it is like riding through the Bible. At every turn some text in the Old or New Testament which alludes to the natural features of the land, springs before one’s mind illumined with a light it could not have before. I know many devout Christians shrink from a visit to the Holy Places for fear of—what? Do not fear! The reality simply intensifies, gives substance and colour to, the ineffable poetry of the Bible. It is simply rapture to see at last the originals of our childhood’s imaginings, and, believe me, the reality becomes more precious in one’s memory even than the cherished illusion. Our ride through this land of little brooks, running clear over pebbly beds under cool foliage, was

refreshing after my “test ride” of yesterday in the dry glare. We soon left this zone of verdure, however, and began the ascent to Jerusalem through that gloomy pass which Our Lord chose for the parable of the Good Samaritan. They are making a road here, but, being as yet bridgeless at the ravines, it is not open to carriages. Our halting-place was Bethany,—most lowly hamlet—and I made a sketch of it at our mid-day halt. We then proceeded to our camping-ground, which W. had selected outside the north wall of Jerusalem, and in skirting the base of Olivet we had again that great view of the city that artists love (and I must say have often exaggerated as regards the height of its rocky pedestal). For the first time there was a “hitch” in the arrangements for the camp. On reaching the north wall no camp was there, and we rode in and out of olive-woods and ugly new roads and dusty building débris in search of it, Isaac appearing, at least, to be quite at sea. At last, after sending him ventre-à-terre successively in several directions, we saw him returning and calling out that he had found it. To our horror we found the people in charge of the baggage had selected the only really hideous and repulsive spot in all Jerusalem, of all places, the Jewish extra-mural colony! There were our white tents pitched down in a hollow full of the back-door refuse from the houses of this unsavoury population, surrounded by youths and bedraggled women who might have just come out of Houndsditch to look on at the preparations of the camp. The idea of a night on this ground was impossible. On catching sight of this state of things W. pushed forward at a gallop at the whole assemblage of servants, muleteers and cook, and the whole amalgamated crowd, and with an unmistakable twirl of his stick told them to “be out of that”; and the muleteers, servants, and cook fell on their knees and with joined hands called out “Pardon! pardon!” In the twinkling of an eye tents were struck and reloaded, dinner preparations bundled away and an instant movement made to the place behind the north wall on Mount Moriah, which W. had fixed upon in the morning. He suspects that he was disobeyed on account of the ease with which the servants knew they would obtain drink from the Jews.

Certainly our final encampment was enchanting, overlooking Gethsemane deep down to the east, with the battlemented walls of Jerusalem before us to the south, and tall pines waving above our tents. The moon was now waxing bright, and never can I forget that evening, as by its light I looked upon these things.

What a change in the temperature here! It is quite cold. My kit is proving well devised for this country. You must be prepared for these very marked changes of temperature in a land which rises so high and sinks to such abnormal depths below the level of the sea in such a small space.

I shall post this in Jerusalem, for to-morrow we set out on a journey during which no post-offices will be found for many days.

Friday, 17th April.

My....—I continue my letter in diary form from notes taken on the march. This morning we left rather late, as the weather was so cool, and after making some purchases in Jerusalem we set out with our faces due north on our long ride into Galilee. It was again an eight-hours-in-the-saddle day, but over such rolling stones that our horses seemed to me to be going at about three miles an hour. It was a relief at the almost impassable places to dismount and lead one’s horse. As W. said, these paths of Palestine seem to have been rather worn by the people’s feet than made by their hands. These bare hills of Benjamin were weary and sad, but what a thrilling view was our last one of Jerusalem from a high point overlooking the ocean of mountains that bore afar off the island of the Holy City and its domes. Good-bye, Jerusalem! good-bye, Olivet! We sat many minutes on our horses looking back at that centre of the world, and then resuming our way a turn in the rocky track shut out the Holy City from thenceforth. We overtook a large wedding party, the men armed with long flintlocks, and the women wearing brilliant dresses. We all moved forward together as far as Bethel. How powerfully this assemblage of men and women and children journeying northward from Jerusalem represented that large company in which were Mary and Joseph, who came along this way, a day’s journey, to the evening halting-place at Beeroth, and found there that the little Jesus was missing. As I was thinking over this and watching the people, we passed a little goatherd who had evidently been out on the hills many days “on duty.” His mother, who was amongst the wedding party, catching sight of her son—about twelve years old—snatched a moment to leave the line of march and ran up to him and kissed him and wept over him, then returning hurried forward to rejoin her companions. That meeting of mother and son, the bending form of the woman in her red and blue drapery, which concealed at that moment the rich dress worn underneath, the little goatherd held close in her arms, formed a group that startled me, with my mind engaged as it was. On reaching the village the men all let off their guns and were met by the people who had remained at home. We made our halt at Bethel. What a place of hard, gritty, arid desolation! Beth-el, “the House of God.” From this great height Lot looked down on the plain of Sodom, then the acme of fertile beauty, where now lowers the Dead Sea! There are now only the dry bones of Bethel left. The goats eat up every green sprout that appears above ground. I could not sketch such blinding nothingness at our halt there. Towards evening the land grew more beautiful as we journeyed on, but so much struggling over boulders and jagged rock ledges made me very glad indeed to perceive the daily signal that we were nearing our camp. That signal is the dashing forward of Isaac at full gallop and the pushing forward of the “flying column” (the man on the chestnut horse with the bags), whose place is at other times in the rear. The staff in camp being warned by these cavaliers of our approach tea is got ready, and very welcome it is on our arrival. W. was on ahead as we scrambled up a higher hill than ever, and when I saw him wave his helmet to cheer me on for a final spurt I knew rest was close at hand. Our camp looked very lovely just at sunset on a plateau overlooking the hills and valleys of green Samaria and the far-off mountain-tops of Galilee! The moon shone brightly and the air felt quite frosty as we went to rest. I always take a little meditative walk before going to bed, a sweet ten minutes each evening. The hurried start in the morning and the rough riding all day leave one little time for quiet thought, and at our mid-day halts, when circumstances permit, I sketch with concentrated intensity against time.

Saturday, 18th April.

To-day was breezy and the country less stony. Waving corn as in Philistia refreshes the eye. We are now in the goodly land of Ephraim, which deepens in richness as we advance. We passed through Shiloh, where the Ark of the Covenant rested so long, and the little Samuel heard the call of God. The place is marked by some old ruins—Roman or Crusader? and a forlorn dead tree lies athwart them. A glorious cultivated plain opened out before we reached our halting-place, Jacob’s Well. How I had longed to see this well, where Our Lord conversed with the Samaritan woman. But I was disappointed at being unable to make the sketch of it I hoped for so much. The well is about five feet below the surface of a mass of ruins. An early Christian chapel once enclosed it, but this has fallen in and all but buried the well. But you can imagine one’s feelings as one rests one’s hand on its edge and realises that Our Saviour sat there as He spoke to the woman who had come to draw water. You remember that it was at this well that He told His disciples to look up at the fields “already white unto harvest.” There they are, those fields, filling the valley of Sychar. But you cannot see them from the well now, in the pit enclosed by ruins, nor the town to which the disciples went “to buy meats,” nor even the two great mountains of Ebal and Gerizim that rise so high quite close by.

This well is like the Cave of Machpelah,—accepted by all as authentic beyond question.

I cantered my horse all the way up to our camp, high up in an olive-wood on the other side of the town, for I must say I was longing to get the ride over and have a good rest. But Society duties awaited me! The ministers of various denominations came to call on us, and when later on the Catholic priest (an Italian) honoured us with a visit I was called upon to take over Isaac’s duties as interpreter.

We went, W. and I, for a pleasant stroll towards sundown, and had a perfectly exquisite view of Nablous, the ancient Shechem, lying between those two mountains whose names rang so sonorously to us all in childhood—the terrible Ebal and the smiling Gerizim. A most perfect, typical Eastern town, this, embowered in orange and pomegranate trees—the home of the nightingale, whose music blends with that of the multitudinous cascades echoing from the over-hanging cliffs. A Turkish sentry came and lit his fire close to our tents, and was suffered to mount his quite unnecessary guard over us all night, with an eye to backsheesh at sunrise.

Sunday, 19th April.

The Day of Rest. No travel to-day. Exquisite Nablous, what a Paradise to rest in! But all was not perfection. We went to Church too early, by mistake, and had to wait an hour before Mass began, passing the time in French small-talk (indeed reduced to a minimum of smallness on my part, for it dwindled away almost to nothing) with the courteous ecclesiastics and the nuns in the garden of the little presbytery. As I was fasting I was not fortified against the subsequent performance on the harmonium during Mass, by a Syrian. On nearing our tent, cheered by the prospect of breakfast, I had another set-back by Isaac’s announcing the imminent arrival of what sounded like “the Rev. Vulture,” the Lutheran minister. Had that individual really been on the swoop I must have fled, but happily that morning call never took place. It is all very well to laugh, but I felt “in the Pit of Tophet.” I have spent the rest of the day in sleep, and in writing to you, and in fascinating strolls through the town with W., and in returning calls. I am nicely burnt by the sun and wind, for nothing could induce me to let a veil blur or dim one single glimpse of the Holy Land.

Monday, 20th April.

Glorious breezy weather with flying cloud shadows. Again eight hours in the saddle, but the Sunday rest has made me quite fresh again. We passed to-day through the hill country of Manasseh. After riding a mile or two out of Nablous our “flying column” came running up on foot to the dragoman in front to ask what was to be done with a poor little stowaway who had begged him to let him ride the baggage horse to escape from his unhappy home. “His mother was dead and his stepmother beat him.” He looked so piteous perched up on the bags, but, of course, we could not kidnap him, and after receiving some money he was put gently down on the roadside. As we rode on we got a last sight of him on the green bank swaying to and fro in his desolate grief, his gown making a little pink dot in the vast landscape. Our mid-day halt was at a fountain in a fig country, and there we talked to the women and girls who were filling their pitchers. One showed me by signs how the figs were a failure this year, the young figs all falling off their stalks before ripening. Her patient acceptance of the inevitable reminded me of the Italian peasants and their “Pazienza, è la volontà di Dio!”

Then we deflected to the left on our journey to visit Sebaste, where St. John is supposed to have been beheaded, and with great probability. The Crusaders built a magnificent Church to his memory there, the ruins of which are very grand. We rode to the site of the gates of the city, along a path lined with classic pillars, and at the end of this avenue we saw the sea, and where Cæsarea, the harbour of Sebaste, once stood. Our camp that evening was at Ain Jenin, an ideal Eastern town. I was not prepared for anything so beautiful as it looked in the evening light, when we emerged in sight of it from a defile between hills. We were well in the Plain of Jezreel, and lo! Hermon at last! In the light of the after-glow we beheld his hoary head from our tents, to the north. Tender moonlight succeeded the after-glow. All the mosques and minarets were lighted up with delicate golden lamps at sunset (for it is Ramadan), as at Jerusalem and Nablous. This place is full of pomegranate trees, with their scarlet blossoms, and of flowering tamarisk.

Tuesday, 21st April.

Off at sunrise, the larks singing over the face of the land. We had a glorious ride through the Plain of Jezreel or Esdraelon, often coming upon the brook Kishon and its little trickling tributaries in their multitudinous windings, and fording the same. What a vast space is here, how Biblical in its majesty, and how troubled too with recollections of battle from remotest ages of Israelitish history down to Napoleon’s time. Deflecting to the right we climbed up to Naim for our halt, memorable for the raising of the widow’s son. There was an immense view from this little bunch of mud houses towards Tabor and Galilee, with a foreground of purple iris. Then descending again into the plain we rode to the foot of Mount Tabor, where, in an olive-wood, and on ploughed land, our camp was pitched. How refreshing it is never to be told we are trespassing in this country.

On arriving I chose to remain and make a sunset sketch of distant Naim on its hill, whilst W. rode up to the top of Tabor.

Wednesday, 22nd April.

Off again at sunrise over the saddle of Mount Tabor. Very rough riding through dells of oak, where the honeysuckle hung in masses and scented the air. Tabor itself is scarcely beautiful in outline, and like the magnified mounds that the old masters intended for mountains. In their pictures of the Transfiguration their Tabors are very like the original. This was our most glorious day’s journey, for it took us to the shores of the Lake of Galilee. Hermon in distant Lebanon was visible ahead of us throughout. We rode up to near the top of the “Mount of Beatitudes,” and then on foot reached the very top, and had our first view of the Sacred Sea from that immense height. Here Christ preached the Sermon on the Mount, and down there, intensely blue, lay that dear lake whose shores were so often trodden by His feet. Hermon rose above the majestic landscape, and a warm, palpitating light vibrated over all. In a scrap of shade from a rock we made our halt, and I had an hour and a half for a sketch. Then we rode down to Tiberias, descending into a furnace, though when once on the shore the breeze was sweet off the water. Tiberias is a dreadful little town, and we were glad to thread its alleys as quickly as possible. Our camp was on a pebbly strand about half a mile south of this, the only, town on these shores that once held such brilliant cities. I made an evening sketch, and before retiring for the night we strolled a long time by those sacred waters in the light of the full moon. The waves were strong, and sounded loud in that great stillness. At such times as this the sense of Our Lord’s Presence is almost more than one’s mortal heart can hold.

We picked up hundreds of shells, which will make appropriate rosaries, mounted in silver, the cross made out of olive wood which I have brought from Gethsemane. I will send you one.

Thursday, 23rd April.

We went by boat three hours’ row to near the mouth of the Jordan, at the north end of the lake, where the grassy slopes are supposed to

be the scene of the miracle of the Loaves and Fishes. It is very difficult to describe to you my enchantment at seeing one after another these places I have longed to see from early childhood, when our beloved father used to read us the Bible every Sunday. The lake was pale and calm, delicately tinted, and there was a heat-haze over everything in the early part of the day. We disembarked under some thorny acacias which gave a deep shade, and I had the delight of making a sketch there of the coast, looking westward, whilst W. went on by boat to the Jordan. Rosy oleanders fringe the water as far as the eye can reach; the “Mount of Beatitudes” and top of Tabor are in the distance, and the site of Capernaum in the middle distance. God has trodden these scenes with human feet; the feeling of sketching them is scarcely to be put before you in words.

The boatmen were very angry at being kept, whilst I finished the sketch, from returning at the right time, for they told us that if the west wind sprang up we should never be able to get home that night. Surely enough we were only able to get as far as Capernaum with hard pulling against a strong west wind, which suddenly changed the whole face of the lake.

Its pale blue was now dirty green and the choppy waves lashed with foam, and so wild did the waves become that the progress of the boat was almost impossible. These sudden and violent gusts that come through the gullies between the mountains are dreaded by the fishermen of to-day as they were in Peter’s time. Fortunately W. had in the morning ordered that our horses should be sent round to meet us here in case the wind arose, and we gladly got on them at this point, having an enchanting ride back and being able at many places to canter our horses. We heard afterwards that the boatmen did not get in till one in the morning. At Capernaum are seen some rich Roman ruins lying tumbled about as though by an earthquake. We rode through the supposed site of Bethsaida, and passed through a portion of the old Roman roadway for chariots, cut through the rock. No accumulation of earth has buried the original surface as elsewhere, so that this lane, with its polished floor of rock, must have undoubtedly been trodden by Our Lord as He passed from city to city. Here are the remains

of a Roman aqueduct, in one place pouring a huge volume of clearest water over a ledge where, no doubt, in the city’s time, a fountain stood. Now the flood from the northern hills disperses itself in abundant streams that rush through dense herbage to the lake. We counted six of these little rivers on our way to Magdala, the birthplace of the Magdalen. We looked down from our mountain lanes to the milk-white strands of the little inlets that border the northern end of Gennesaret, and I wondered at which of them the various episodes of the Gospel took place—Our Lord preaching from the ship pushed out a little way to be free from the jostling crowd on shore—the embarkation for the miraculous draught of fishes——. Besides oleanders the pomegranates grow all along this shore in dense masses half embedded in teeming vegetation.

Magdala is a tiny mud hamlet with a single palm. There are splendid fig-trees here. Herds of oxen and goats and flocks of sheep browse knee-deep in the rich grass.

Our dragoman took us this time through the whole length of the town of Tiberias. It happened to be a great Jewish festival, and the men had all freshly oiled and curled their side locks, which dangled from under immense round fur caps, and the women wore artificial flowers in their hair and were clothed in velvets of splendid hue. It was strange to see them thus attired, coming upon them so suddenly when entering the town from the wilderness. The lanes were stifling and unwholesome, the children pale and sickly, and all had that same blighted look I noticed at Jerusalem. None of them were tanned, but remained white under such a sun! It was a relief to come out at the other end and canter back along the margin of the “Sea” to our camp, for that ride through Tiberias had oppressed and saddened me.

Friday, 24th April.

An early start as the sun rose over those dark cliffs of the country of the Gadarenes down which the possessed swine careered to the abyss. Good-bye, blessed Sea of Galilee! We had our last look from the immense height near the “Mount of Beatitudes,” and thence we turned south-west on our way to Nazareth over the hills of Zebulon.

Young shepherds were piping on little fifes on the hills. The country became uninteresting

(comparatively!) after we left the immediate surroundings of the lake till we came to Cana of Galilee, where we halted, and where I made my only “failure” sketch.