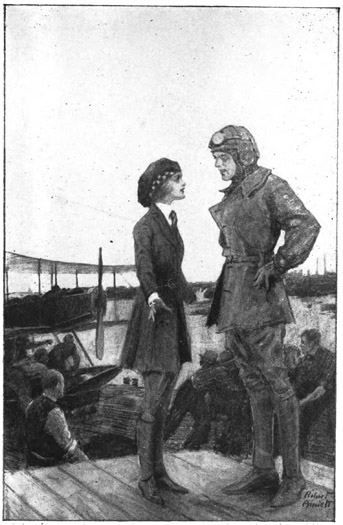

She looked like a glorious, slender boy in the riding breeches and puttees she had thought appropriate for the adventure.

She looked like a glorious, slender boy in the riding breeches and puttees she had thought appropriate for the adventure.

Fred la Mothe was speaking. After a certain number of beverages composed of Scotch whisky, imported soda, and a cube of ice, it was a matter of comparative ease for him to exhibit a notable fluency. After two o’clock in the afternoon Fred was generally fluent.

“‘’Tain’t safe,’ I says to him. And the wind was blowin’ enough to lift the hair out of your head. ‘I wouldn’t go up in the thing for the price of it,’ I says, ‘and, besides, you’re seein’ two of it. Bad enough drivin’ a car when you’re lit up,’ I says, ‘but what these flyin’ machines want is a still day and a man that’s cold sober. You just let it rest on its little perch in the bird-cage.’”

Fred refreshed his parched throat while his four companions waited for the conclusion of the tale. “‘You’ll bust your neck,’ I told him.

“‘Ten to one,’ says he, ‘I round Windmill Point Light and come back without bustin’ my neck. Even money I make it without bustin’ anything,’ says he.

“‘Dinner for four at the Tuller to-night that the least you bust is a leg,’ I says, and the wind whipped the hat off my head and whirled it into a tree.”

Fred stopped, evidently mourning the loss of his hat.

“Well,” said Will Kraemer, impatiently, “what happened? Did he go up?”

“Him?... I paid for that dinner, but, b’lieve me, there were times when I thought I’d have to collect from his estate. Ever see a leaf blowing around in a gale? Well, that’s how he looked out over the lake. Just boundin’ and twirlin’ and twistin’, but he went the distance and came back and landed safe. Got out of the dingus just like he was gettin’ off a Pullman. Patted the thing on the wing like it was a pet chicken. ‘Let’s drive down to the Pontchartrain,’ he says. ‘Likely the crowd’s there.’ Not another darn word. Just that.”

“Trouble with Potter Waite,” said Tom Watts, “is that he just naturally don’t give a damn. If he’s going to pull something he’d as lief pull it in the middle of Woodward Avenue at noon by the village clock as to pull it on the Six Mile Road at midnight.”

“No pussy-footin’ for him,” said Jack Eldredge. “My old man was talking about him the other night. Day after he cleaned up those two taxi-drivers out here in front. ‘Don’t let me hear of you running around with that young Waite,’ he says. ‘He’s a bad actor. You keep off him.’”

“He’s a life-saver,” Fred La Mothe joined in. “When dad lights into me I just mention Potter, and dad forgets me entirely. You ought to hear dad when he really gets to going on Potter.”

“I’m no Sunday-school boy—” said Brick O’Mera.

“Do tell,” gibed Eldredge.

“—but I’ll say Potter is crowdin’ the mourners. I wouldn’t follow his trail a week steady.”

The others waggled their heads acquiescently. Even to their minds Potter Waite traveled at too high speed and with too little thought of public opinion. About that table sat five young men who were as much a result of a condition as outlying subdivisions are the result of a local boom. Of them all, La Mothe came from a family which had known moderate wealth for generations, but it had grown swiftly, unbelievably, during the past few wonderful years, to a great fortune. Of the rest, Kraemer and O’Mera were the sons of machinists who, a dozen years before, would have considered carefully before giving their sons fifteen cents to sit in the gallery at the old Whitney Opera House to see sawmill and pile-driver and fire-engine drama. The automobile had caught them up and poured millions into their laps. Eldredge was the son of a bookkeeper who, fifteen years ago, had drawn fifty dollars at the end of each month for his services. For every dollar of that monthly salary he could now show a million. Watts was the son of a lawyer whom sheer good luck had lifted from a practice consisting of the collection of small debts, and made a stockholder in and adviser to a gigantic automobile concern. And these boys were the sons of those swiftly gotten millions. They had forgotten the old days, just as Detroit, their home city, had forgotten its old drowsiness, its mid-Western quietness and conservatism.

One might compare Detroit to a demure village girl, pleasing, beautiful, growing up with no other thought than to become a wife and mother, when, by chance, some great impresario hears her singing about her work and it is discovered that she has one of the world’s rarest voices. From her the old things and the old thoughts and the old habits of life are gone forever. The world pours wealth and admiration at her feet and her name rings from continent to continent. So with the lovely old city, straggling along the shores of that inland strait. She has become a prima donna among cities. The old identity is gone, replaced by something else, less homely, but mightier, grander. Her population, which, within the memory of boys not out of high-school, numbered less than three hundred thousand souls, was now reported to be thrice that, and, by the optimistic, even more. Her wealth has not doubled or trebled, but multiplied by an unbelievable figure, and she has spent it with unbelievable lavishness.

Where once were cobblestone pavements and horse-cars are countless swarms of automobiles; where once were meadows, pastures, wood-lots, are tremendous plants employing armies of men, covering scores of acres, turning out annual products which bring to the city hundreds of millions of dollars. In the history of the world no city has come into such a fortune as Detroit, nor has there been such universal prosperity, not to employer alone, but to employees, and to the least of employees. It seemed as if the day had arrived when one asked, not where he should get money, but what he should do with his money. So Detroit spent! It built magnificent hotels; it created palaces for its millionaires, and miles upon miles of homes—luxurious, costly homes for those whose handsome salaries passed the dreams of their youth, or whose fortunes, built up by contact with the trade of purveying automobiles to an eager world, had not even been hoped for ten years before. Even the laborer had his home. Why not, when one manufacturer paid to the man who swept his floors the minimum wage of five dollars a day?

That was before the war, before a solemn covenant became a scrap of paper and the world fell sick of its most horrible disease. Then Detroit was rich, was spending lavishly but not insanely. With the coming of war there was a halt, a fright, a retrenchment, a hesitation, for no man knew what the next day might bring. But as the next day brought no disaster, as it became apparent that the coming days were to bring something quite different from disaster, Detroit went ahead gaily.

Then came strangers from abroad, speaking other languages than ours, and men began to whisper that this plant had a ten-million-dollar contract from Russia for shrapnel fuses; this other plant a twenty-million-dollar contract for trucks; this other a fabulous arrangement for manufacturing this or that bit of the devil’s prescription for slaughtering men—and the whispers proved true.

The automobile brought amazingly sudden wealth; munition manufacture added to it with a blinding flash—and Detroit came to know what spending was.

These five young men, sitting in mid-afternoon in the Hotel Pontchartrain bar, were a part of all this; their life was the result of it; the thoughts, or lack of thoughts, in their minds, derived from it inevitably, remorselessly. They were castaways thrown up in a barroom by a golden flood.

To four of them a nickel for candy had been an event; now, without mental anguish, each of them could sign a dinner check which stretched to three figures, or buy a runabout or a yacht, or afford the luxury of acquaintance with the young woman who stood fourth from the end in the front row.

Let them not be chided too harshly. The fault was not theirs wholly, but was the inevitable result of their environment. They played at work, drew salaries—but could spend their afternoons in the Pontchartrain, in the Tuller, on the links or at thé dansant. They knew no responsibility to man, felt but a hazy responsibility to God, and as for their country, they had never thought about its existence.

They talked of the war, were pro-Ally with the exception of Kraemer, whom they baited when the fit was on them. Kraemer had been born on Brady Street. His grandfather was a ’forty-eighter. It was natural that he should see eye to eye with the land from which he derived his blood. Of them all, he alone took the war with seriousness, so they baited him at times, and he raged for their amusement.

They began the sport now.

“If the Kaiser only had the grand duke,” said La Mothe, “he might stand some show. Look what he’s done and what he had to do it with! I don’t figure it’ll last much longer. Everybody’s lickin’ Germany.”

Kraemer banged the table. “You’ll see,” he said, passionately. “The war would be over now if it wasn’t for the neutrality of the United States. This country’s just prolonging the agony. If it wasn’t for the munitions the Allies get from here, we’d be in Paris and London and St. Petersburg. Devil of a neutrality, ain’t it? Look here....”

“Rats!” said O’Mera. “Where’s Potter, anyhow?”

“Haven’t seen him to-day. Ought to be driftin’ in.”

“He’s over at police headquarters,” said a new voice, and Tom Randall beckoned a waiter and sat down at the table.

“Pinched again?” came in chorus.

“No, but he’ll probably get himself pinched before he’s through with it. Know the von Essen girl?”

“Hildegarde, you mean? Sassy one? Swiftest flapper that ever flapped?”

“That’s the darlin’. Well, she drives that runabout of hers down Jefferson again, doin’ nothin’ less than forty-five and makin’ real time in spots. Seems she’s been fined pretty average regular. Well, traffic cop gets her and makes her haul up to the curb and crawls right in beside her. Uh-huh. And off they go to the station, her lookin’ like she could bite off the steerin’-wheel. Well, Potter and I are comin’ along in his car, and we see the excitement and tag after. You know Potter?”

“We do!”

“‘It’s that von Essen kid, isn’t it?’ he says to me, and I agree with him. ‘She’s been caught too regular,’ he says. ‘They’ll be nasty. Better trail along and see if we can help out.’ So we did. Got to the station simultaneous and adjacent to them, and out jumps Potter.

“‘Afternoon, Miss von Essen,’ says he.

“‘Mr. Waite,’ she says, cool as a bisque tortoni.

“‘Pinched?’ says he.

“‘Ask him,’ she says, and jerks her head toward the cop, who is clambering down.

“‘She is,’ says the cop, ‘and this time she gits what’s comin’ to her. She been a dam’ nuisance,’ he says, ‘and this here time I’m goin’ to put her over the jumps. Git out and git inside,’ he says to her.

“Well, Potter sort of edged up to the cop and looks him over and says, ‘I don’t really see why this young lady has to go inside. You can make your complaint, and that about ends your usefulness.’

“‘She stays,’ says the cop, ‘and if I got anything to say about it, she sleeps on a plank.’

“‘You wouldn’t care to do that, would you, Miss von Essen?’ says Potter, with that grin of his, and I made ready to duck, because when he grins that way—”

“We know,” said the boys.

“‘Now you listen to reason,’ says Potter. ‘A police station is no place for a young lady. It doesn’t smell pleasantly. So she doesn’t go in. If bail’s necessary or if anything’s necessary, I’m here for that. But omit the stern policeman part of it.’

“‘Git out and come in,’ says the cop to the girl.

“‘You and I are going in, friend,’ says Potter, and he took hold of the policeman’s arm. ‘We’ll fix this up—not the young lady. Come on,’ says Potter, with his left fist all doubled up and ready.

“The cop knew Potter, so they parleyed, and then they walked under the porch—you know the entrance to the station—and in a couple of minutes out comes Potter, looking sort of sneering and shoving a roll of bills into his pocket.

“‘Seems there was some mistake,’ he says to Miss von Essen. ‘It wasn’t you who broke the speed ordinance; it was I. I’ve arranged the mistake with the officer. Now, for cat’s sake, cut it out. You’ll be breaking into print good one of these days, and there’ll be the devil to pay ... or breaking your neck. You’ll get yourself talked about if you don’t ease off some.’ And,” said Randall, “he hardly knows the girl. Some line of talk for Potter to ladle out!”

“What did she say?”

“Her eyes just glittered at him. She’s a handsome little cat, but I’ll bet she can scratch. ‘Coming from you,’ she says, ‘that advice is thrilling.’ Her engine was still running. She slammed into gear, stepped on the gas, and shot over to Randolph Street.

“Potter looked after her and chuckled. ‘Promising kid,’ he said. ‘You chase along, Tom. They want me inside.’ So here I am. Guess he can take care of himself.”

“Here he comes,” said La Mothe. “Didn’t get locked up, anyhow.”

A tall young man who did not need padding in the shoulders of his coat was making his way between the tables. He wore a plaid cap jauntily on his yellow hair. He was not handsome, but at first glance one was apt to call him handsome—if he were in good humor. You liked his face, except at times when he was alone, or thoughtful. Then it distressed you, for you could not make out the meaning of its expression. Then his blue eyes, which were twinkling now, looked dark and brooding. He had a way of looking dissatisfied—and something worse, more disquieting—something not to be defined. Ordinarily his face was such as to draw men to him, even older men who quite disliked him and used his mode of life as a text for dissertations on what the young man of to-day was coming to.

One thing might be said with safety—he possessed personality. When he was one of a group he dominated it. He was not a boy to leave out of the reckoning.... When one of his “fits,” as his friends called them, was dark upon him, even those who knew him best and regarded themselves as closest to him were a bit uneasy in his company. The most hardy and reckless of them was moved at such times to go away from there, for Potter Waite usually set out on some mad enterprise when that mood was on him. He would set a pace few cared to follow.

“You never know what he’s thinking about,” Kraemer said, frequently. It was true. But you did not know that he was thinking, and that he could think. Also he never followed, he led. For him consequences did not exist. If he set out to do a thing, he did it, and let consequences take care of themselves. And, as the boys complained, he went his reprehensible way with a brass band. The idea of concealing his escapades seemed not to occur to him.

“What’ll you have?” called Randall, whose waiter had come to him.

“A stein, a quart of Scotch, and a bottle of soda,” said Potter.

“What’s that, sir?” said the waiter.

“Deliver it as ordered,” said Potter, with a boyish smile that got him quicker and better service than other men’s tips.

The waiter obeyed and the boys watched with interest. Potter poured a generous half-pint into the stein upon the ice, and filled the stone mug with soda.

“I’m goin’ to git,” said Jack Eldredge. “Somethin’s goin’ to bust loose around here.”

Potter sat back comfortably and sipped from his stein. He appeared unconscious that, from other tables, glances were directed toward him, and that men standing at the bar mentioned his name and pointed him out to companions. He began chatting pleasantly.

“Not pinched, eh?” asked Randall.

“Suppose I’ll get mine in the morning,” Potter said, without interest.

“I’d ’a’ let her take her medicine,” Randall said. “It wasn’t any of your funeral.... Didn’t even say thank you.”

Potter looked at him musingly. “That was the best part of it,” he said, presently. “Sort of proves she’s being natural; not four-flushing like some of these girls. They’d have burbled and kissed my hand—stepped out of character, you know. She didn’t.”

A boy came into the room with an armful of papers. What he called could not be heard distinctly above the din of the place. Potter raised his hand and the boy threw a paper before him. The young man glanced at it, seemed to stiffen. He sat back in his chair while the others watched him, arrested by something in his manner, something portentous.

He stood up and looked from one to the other of them. Then he laid down the paper slowly.

“The Lusitania has been torpedoed,” he said, in a quiet voice, “without warning. Hundreds of Americans are lost—women and children.” He stopped and repeated the last words. “Women and children.” For a moment he stood motionless.... “It means war,” he said.

Every eye was on him. He held them. He stopped them as if they had been so many clocks with their hands pointing to this fateful hour. He made them feel the event.

Nobody spoke. Potter turned very slowly and surveyed the room, then, still very slowly, he walked out of the room without a word or a nod. His stein was left, scarcely touched, before his chair.

Potter Waite stood a moment at the curb beside his car, looking at the heart of this great new city. At his right, Cadillac Square stretched broadly away to the County Building’s square tower. Within his memory this handsome space had been a public market, unsightly, evil of odor, reeking with decaying vegetables and the refuse of the meat-stalls. To-day it was overcrowded with parked automobiles. At his left opened the Campus Martius, bisected by the magnificent width of Woodward Avenue. There, on its little irregular plot, squatted the City Hall, shabby, slatternly, forbidding. It seemed, against the background, the palisade, of upreaching sky-scrapers of terra-cotta and brick, to typify that thing we tolerate as municipal government. As was the shabby building to its clean, its magnificent, neighbors, so was the thing it contained—the government of a great city—to the governments of private enterprises which had made that city a place to excite the envious admiration of her sister municipalities.

Potter frowned at the thought. The huge machine of government was made up of such parts, of common councils, of mayors, of state legislatures, of national legislatures, differing only in degree, but wrought of kindred materials. It was this machine with which the country would make war.

“It won’t work,” Potter said to himself. “It hasn’t the stroke or the bore....”

He stood still looking at the teeming Campus, following its currents and cross-currents and eddies with eyes darkened by thought. It was a current worthy to pass between magnificent banks. The sidewalks eddied with never-motionless men and women; with human beings whose errands hurried them on. Potter studied them with interest. Their faces were mobile, alert, intelligent, forceful. There was a capability about each individual; there was something distinct about each atom in the crowd.... Here, after all, was the great machine of government. Here was that from which government derived; here was that which would make war, which would fight the war. Walking down that street was a potential army, and the mothers of a potential army.

It was these who had made possible, who had created, the terra-cotta sky-scrapers; it was these who had made possible that marvelous procession of automobiles which taxed the width of Woodward Avenue; it was these who had made possible the building up of that miracle of industrial life that stretched around the town like fortifications around some European city—but fortifications holding the city safe, not from a foreign invader, but from an economic invader. Factory-fortresses preserving the prosperity of the town.

He continued to eye the crowd, and his eyes became less deep and dark. He raised his head without knowing that he raised it. A feeling of pride was upon him.

“Here’s the thing—the real thing,” he said within himself. “This is the machine; the stroke is there and the bore is there ... if they can be made to see and to understand.”

Potter stepped into his car and drove out Woodward Avenue, and thence down a side-street to that mammoth, unbelievable mass of buildings which all the world, through advertisements, would recognize as the plant of the Waite Motor Car Company. Since the day the first brick was laid, a dozen years before, building had never ceased. The plant had never caught up with itself, had never been able to produce the number of automobiles required of it by the public. As far as the eye reached were clean, splendid structures; the ragged outline at the end, dimly seen, was caused by steel not yet covered by brick, by brick walls rising to wall in new space in which to manufacture yet more thousands of the Waite motor-car.

To all this, to this concrete, visible, tangible fortune, Potter Waite was sole heir. It was not like wealth in stocks, bonds, securities. It was not in promises to pay, in paper standing for something more substantial. It was there. It could be beheld in the mass. Perhaps a hundred millions of dollars actually reared themselves in brick and steel, in splendid, efficient machinery. Potter had grown up with it, was accustomed to it. Unlike the casual passer-by, he was not awed by it.

He leaped from his car and ran up the broad flight of stairs leading to the offices on the second floor.

“Dad in?” he flung at the man who sat behind the information-desk.

“Yes, but he’s occupied, Mr. Waite. I shouldn’t go in.”

Potter strode past. The man rose as though to call him back, and then sat down with a shrug. Potter flung open the door of his father’s office, flung himself through it.

“Dad, have you heard?” he said, abruptly.

Fabius Waite looked up, frowned. “I’m busy. Weren’t you told?” he said.

Potter glanced at the other occupants of the room; recognized Senator Marvel, did not recognize the other. He nodded to the Senator.

“The Germans have torpedoed the Lusitania,” he said. “It was without warning. More than a hundred Americans drowned—women and children ... like rats,” he finished.

The Senator was on his feet. The news had been a sudden, bewildering blow to him. “What’s that? Are you sure? Where did you get it?”

Potter threw a paper on the desk over which the Senator and the stranger crouched with manifest excitement. Not so Fabius Waite. He did not glance at the paper, nor did he seem moved. His broad, clean-shaven, patrician face showed no emotion except, perhaps, a shade of irritation at the others’ reception of the tidings. Potter said to himself that his father would sit outwardly unmoved, unruffled, not in the least disarranged mentally, if word were brought him that the dissolution of the universe had commenced. It was true. Fabius Waite would study the information and determine his course of action before he gave a sign that the most sharp-eyed might read.

“My God!” exclaimed the man whom Potter did not know.

“What’ll it mean?... What will it mean?” the Senator asked, in an awed, frightened voice.

“What can it mean but war?” Potter said.

His father merely glanced at him, not contemptuously, not rebukingly, in fact, not as if Potter were a human being at all, but as if he were some piece of the room’s furniture to which attention had been called.

“When you men are through scrambling over that paper,” he said, quietly, “I’ll look at it myself.” He did not stretch out his hand for the paper, did not seem to suggest that it be given to him, but simply stated a fact. Potter came near to smiling at the alacrity with which Senator and business man abandoned the news sheet and pressed it upon his father. The Senator was a big man in Washington and in Michigan, Potter knew. The stranger looked like a man of importance, yet Fabius Waite dominated them, made their personalities colorless by the simple fact of his presence. He merely sat there—and they were dwarfs beside him.

“The people,” said the Senator, “there’ll be no holding them back. They’ll sweep us into war—as they did with Spain.”

“I heard there were munitions shipped on the Lusitania,” said the stranger.

Fabius Waite paid not the minutest attention to them, but read calmly, appraisingly, from beginning to end what the paper told of the sinking of the Lusitania. When he was done he folded the paper neatly and laid it on his desk.

“There were munitions,” said the Senator, “and people were warned by advertisements in the paper to keep off that boat.”

“What’s the difference?” Potter demanded. “Are we going to let them murder our citizens like this—and put up such an excuse as that?”

“Citizens had no business on the boat,” said the stranger. “They brought it on themselves.”

“There’s got to be war,” said Potter, his eyes traveling uncertainly from Senator to business man—to his father, where they remained. “There’s no other way. What else can be done about such a thing?”

“For one thing,” said Fabius Waite, coolly, “we can stop jabbering and think about it.... You especially, Potter. If you must wag your tongue, go back to the Pontchartrain bar and wag it for the benefit of the gang of loafers you train with.... Senator, what suggests itself to you?”

“I must get to Washington. The Senate doesn’t want war, I can vouch for that.... But the people.... Perhaps the President can hold them.”

“I gather from your words that he’ll be willing to try?”

“He’s the last man in the country to want war.... There’ll be no war. Those German dunder-heads! Do they want to pull the whole world down about their ears?”

“They’re fools,” said the stranger.

“We won’t argue about their wisdom. Whether they were wise or foolish, they seem to have sunk the Lusitania.” Fabius Waite paused. “And when all’s said and done it won’t be the Senate nor the President nor business which determines what we will do about it. It’s the people who will make up their minds. Don’t lose sight of that.”

“Public opinion can be molded.”

“For a while and to an extent.... I believe this thing can be handled so that nothing will come of it. It will take careful handling. You agree with me, do you not, Senator, that neither the people nor the business of the Middle West want war?”

“Certainly I do.”

“I have no doubt you will intimate to the President that you have grave doubts if the Middle West will follow him into war—will back him up in any belligerent attitude he may have in mind to assume.” Fabius Waite’s eyes were on the Senator’s face, and none could tell what thoughts stirred behind them. He did not order, did not direct, did not suggest, but he was imposing his will on this imposing member of an august body as surely and as relentlessly as if he held a revolver at the Senator’s head.

“I feel it my duty to intimate as much to him,” said the Senator.

“There must, of course, be a protest,” said Fabius White. “News that the President is preparing a note to the German government will hold the people in check. I incline to believe they will wait for it to see what the President thinks.... If it should take time to prepare, so much the better. It would give the country time to cool off.”

“The people have seen what war means,” said the Senator. “They’ve seen Belgium and France.... They’ve no stomach for a dose like that. Handle this thing right—let them get over the first shock of it—and the excitement will die down. The people are sheep.... Yes, you’re perfectly right about delay.”

Potter had hurried to his father, his soul a flame of emotion. The flame was being quenched. The boy stood silent, looking from one to the other of these men, hurt, amazed. Just why he had come or what he had expected his father to do he did not know. Impulse had brought him. The word patriotism was not in his vocabulary, as it was not in the vocabularies of millions of Americans on that seventh day of May. But some spring had been touched, something had been set in motion by the news of that atrocity which would be heralded from one end to the other of the Germanic Empire as a splendid feat of arms. The thing was wrong: the evil of it had seared through to the uneasy soul of the boy and had set afoot within him something which he did not understand as yet.... He was not able now to say, “Civis Americanus sum.”

It was not reason that had brought him. It was no conscious surge of loyalty to his country. It was something—something he felt to be right. Perhaps there was a tinge of adventure in it; perhaps his youth heard the rolling of martial drums and saw the unfurling of flags of war.... But he was right and these men were wrong. That he knew.

He wondered at the men. There had been no word of sympathy for the dead; there had been no cry of anger wrung from them by this affront to the honor of the nation; there had been but one thought—dollars. Business came first. The prosperity of dollars and cents filled their minds to the exclusion of all other prosperities. Even the Senator, servant and representative of the people, was not serving and representing the people. He, too, saw only the effect of this thing on business.

“Does everybody think like this?” Potter wondered. It might be so. His friends at the table in the Pontchartrain bar had been surprised at the news, but he considered their actions those of men who had not been shocked or those of men enraged. Perhaps they, too, were of one mind with his father.... Perhaps all the people were of that mind. Perhaps that was the sort of people the American nation had grown to be....

“Dad,” he said, “if Mother had been on board—”

“She wasn’t,” said Fabius Waite. “Senator, this is mighty ticklish, and it will grow more ticklish. This one act can be smoothed over, but many recurrences of it cannot be smoothed over. Isn’t there some machinery to set afoot forbidding American citizens to cross the ocean? That would do it.”

“I wouldn’t care to introduce such a resolution,” said the Senator, “but probably somebody can be got to do it.”

“We’ve a right to travel,” Potter said, hotly. “Didn’t we fight a war about that once? You don’t mean to say, Dad, that you actually would have this country admit that it was afraid to claim its rights.... The world would laugh at us.”

“Let it,” said his father. “Another year or two of this war and this nation will top them all. We’ll be the financial rulers of the world. We’re getting there now, and nothing must happen to set us back.”

“And the world will despise us,” Potter said, bitterly. He was beginning to see more clearly now. He paused. This attitude of mind he was witnessing could not be common to all the people. He would not believe it. “Dad, think bigger. You men are wrong. You can’t head this off. It means war.... It’s got to mean war. And war means armies and cannon and shell—and aeroplanes. We’ve got to have them all. Think, Dad, and you’ll realize it.... Take a telegraph blank, Dad, and write the President. You can help with this plant; every other plant like it can help. Wire the President that this plant is at the disposal of the country for any use the country can put it to.... Tell him you’re with him. Tell him you can make guns or shrapnel-cases or motors for him as well as for England or France or Russia—as you are making them.... And aeroplanes. We’ll need thousands of them.... Give that job to me, Dad. I know aeroplanes—”

“You know mixed drinks and chorus girls and traffic cops,” his father snorted.

“You won’t do it?”

“Don’t be a fool.”

Potter turned and walked out of the room. He stopped at the information-desk. Here sat a man who worked for wages, a common citizen. Here sat the sort of man who made up the bulk of that crowd he had watched on Woodward Avenue.

“Dickson,” he said, “the Germans have sunk the Lusitania and killed a hundred Americans.”

“Awful, wasn’t it? I just heard.”

“What are we going to do about it?”

“Why—we’ll make ’em pay for it, that’s what. We’ll collect damages, millions of dollars.”

“Money?” said Potter.

“You bet, Mr. Waite. Money.”

“Is that all? Will that satisfy you?”

“Isn’t that enough?” asked Dickson, in real surprise. “What more can anybody ask?”

“You don’t want to fight? You don’t think it means war?”

“Great heavens, no! War!... We don’t want any of that in ours. I guess this country won’t mix in any wars. We’ve been seeing what war means. Anyhow, what should we fight for? England and the Allies are going to lick Germany, aren’t they? Well, let them.”

Potter turned on his heel. He had his answer.

Once more he got into his car and whirled down-town. Once more he stopped before the Pontchartrain and entered the bar. His friends were not there, but he sat down at a table and ordered a drink; he ordered another drink—and another....

His eyes were dark and brooding; the restless urge to recklessness was upon him—that smoldering fire which had made him a young man to be looked upon askance by the respectable. His face was set—and he drank.... Fred La Mothe came through the revolving door, saw Potter, studied his face and his attitude for a moment, and then quietly withdrew. He knew the signs, and had no desire to be in Potter’s company from that hour on.

He sat alone at his table, brooding, drinking from time to time. He felt no hunger, did not arise to eat. The lights came on and still he sat. The room was thronged with the early-evening crowd, and Potter glowered at them—and ordered other drinks.

Presently he stirred uneasily; the spirit of unrest, of recklessness was working within him, urged on by liquor. He pushed himself to his feet, and stood, not too steadily, and his eyes seemed to flame as he glared over the crowd. His face seemed to flame, to be kindling from some fire that surged up from depths inside him. His yellow hair, brushed back from his brow, added to the flamelike semblance of him.

He struck the table with his fist and a glass danced over the edge to smash on the floor.

“It’s a hell of a country,” he said, loudly, “and you’re a hell of a lot of men....”

The room fell silent, and every face was turned toward him. He glared into the upturned eyes.

“You’re a lot of crawling, sneaking, penny-chasing rabbits,” he said, distinctly. “Brag and blow—that’s you.... And then somebody kills your wives and babies and you haven’t the guts to kill back again. You’re afraid, the lot of you. You won’t fight. If anybody says war you crawl under the table.... Americans!... I’d rather be an Esquimo.... If anybody slapped your faces you wouldn’t fight.... I’ll show you. I’ll show you what kind of cattle you are.... Now, if there’s a fight in you, come and fight....”

He lunged forward and struck a man, upsetting him against a table. The place was in an uproar. “It’s young Waite—look out. He’s a bad actor.... Call the cops.” Potter swayed forward into the throng at the bar, striking, striking. In a moment he was the center of a maelstrom of shouting, scuffling men—and his laugh rang above their shouts. They struck at him, clutched at him; waiters and bartenders tried to force their way to him. He was pushed back and back, still keeping his feet, still lashing out with his fists, his eyes blazing, his yellow hair rumpled and waving, his reckless laugh dominating the turmoil. His back was against the wall. Before him now was a clear semicircle which none ventured to cross, and he laughed in their faces.

“Fifty to one,” he jeered, “and you’re afraid.”

A couple of policemen shouldered their way through, recognized Potter, and stopped. “Cut it out now, Waite,” said one of them. “Cut it out and come on.”

Potter’s answer was to step forward and strike the officer with all his strength. The other officer did not parley. His night stick was out. He raised it, brought it down on Potter’s yellow hair, and the whole room heard the thud of it.... Potter stood erect the fraction of a second, then the stiffness went out of his body and he sank to the floor a shapeless heap....

The morning papers printed Potter’s picture and news stories of this his most reckless escapade. They also printed moral editorials which, with singular unanimity, pointed out facts concerning young men with too much money, no regard for their citizenship, and mentioned disgracing an honorable name.

When the heir to a hundred millions of dollars is arrested in this country for any act less than murder, he does not expect to sleep in a cell. The police do not expect him to sleep in a cell, and the public would be astonished—and a little vexed—if he were compelled to do so. They would be vexed because in the event of his detention, they would be deprived of the pleasure of railing against our institutions and of saying to their neighbors in the street-car that, “a man with enough money can get away with anything.”

“Couldn’t you bring in a kid without usin’ the wood?” the lieutenant at the desk said to the officer who had floored Potter. It did not seem fitting to that lieutenant that a hundred millions of dollars should have its scalp abraided by a night stick.

“Kid, hell!” said the officer. “If you’d ’a’ seen the wallop he handed Tom!”

Potter clung to the edge of the desk, dizzy, swaying, his head not clear between blow and drink.

“Here,” said the lieutenant, “come in here and lay down. Want I should telephone anybody—or git a doctor?”

“No,” said Potter, sinking on the lounge and closing his eyes.

The lieutenant went out and called the superintendent on the telephone. “Got young Waite here,” he said. “He tried to tear the Pontchartrain up by the roots and Kerr had to drop the locust on him a bit. What’ll I do wit’ the kid?”

“Hurt?”

“Didn’t improve him none.”

“Drunk?”

“So-so.”

“Send somebody over to the Tuller with him and have him put to bed.”

It was not for the public to know that the superintendent had two sons who were employed in the Waite Motor Car Company’s plant—for whom he desired fair prospects and promotion.

So Potter slept in an excellent hotel bedroom instead of a cell. He awakened in the morning with a head that was very sore; dressed and went down to the office.

“Your car is out front,” said the clerk. Even that detail had been attended to by a solicitous police force.

At breakfast he read a paper on whose first page he divided honors with the Lusitania. He was not interested in what was said about himself; at first he was not especially interested in what was said about the Lusitania, but as he read his interest grew, changing to hot anger as he read the still incomplete list of the dead. More than one individual was there named with whom Potter had broken bread.

Even in the editorial there was no demand for war; there was astonishment, there was wrath, but it seemed to Potter there was some effort to find an excuse for Germany’s act.... Passengers warned.... Munitions.... Possibility of internal explosion.... Wait for particulars. The attitude of the paper was not quite his father’s attitude, not so frank, but he was able to see it was his father’s attitude disguised for popular consumption. And he was intelligent enough to realize that the finger of that paper was on the public pulse; that, without doubt, the paper was dealing with the situation as the public wanted it dealt with—a public not willing to resent blow with blow.

At the next table a man was saying, “Just because they’ve killed a thousand or so is no reason for us to get into it. War would mean killing another hundred thousand or maybe half a million. Because they’ve killed a thousand, should we let them kill a hundred times as many more? That’s sense.... Make ’em pay for it....”

“What could we do, anyhow?” asked the other. “Might get in with our navy, but there isn’t anything for a navy to do. Couldn’t send an army across three thousand miles of ocean.”

“Right. I’m for the Allies, but my idea is we can help a lot more by staying neutral and sending ’em all the munitions they want.”

“My idea exactly,” agreed the other.

That was it. What could we do? We had no army. Potter had been told that Uruguay had more artillery than the United States. There was no ammunition!... The United States was ready for peace, and the old absurdity about a million squirrel-shooters was gospel in the minds of a hundred millions of people. A million squirrel-shooters armed with what?

Potter got up from the table and went out to his car. He wanted to be alone; he wanted fresh air; he wanted to work off the various uncomfortable sensations that possessed him. He drove recklessly out Jefferson Avenue to the Country Club. At this hour it was deserted save for servants. It would do him good, he thought, to play around alone, without even a caddy, so he donned flannels and shoes, and carried his caddy bag to the first tee.

Somebody else was teeing off—a girl. Potter did not glance at her, but dropped his bag with a clatter and sat down on the bench to wait till she should get out of his way.

“How do you do?” said the young woman.

Potter stood up automatically. “Good morning, Miss von Essen,” he said, without interest.

She turned her back on the ball she had been about to address and walked toward him, slender, graceful, yellow hair blowing out from beneath a tilted tam-o’-shanter. Her face was thin, not especially pretty at first glance, but arresting. The features were distinct, and the expression, even in repose, was one of eagerness—such an expression as one associated with the possession of wit and daring. The expression was akin to pertness, but was not pertness. One knew she could play golf or tennis. One knew she had been a tomboy. One knew she had temper. Her whole appearance and bearing were a perpetual challenge. “Come on,” it seemed to say. “Whatever it is, if there’s a chance to take, let’s do it.” Potter knew she was a girl about whom there had been shakings of the head, not so much because of what she had done as because of what she might do. Conservative mothers preferred some other friend for their daughters—and you felt immediately that Hildegarde von Essen delighted to tantalize such matrons and to set their tongues clacking.

“You gave away something yesterday that you needed yourself,” she said, with directness.

“No,” said Potter, amused as at a pert child. She was only nineteen. “What was it?”

“Advice. ‘You’ll be breaking into print good one of these days, and there’ll be the devil to pay,’” she quoted. “‘You’ll get yourself talked about if you don’t ease off some,’ says you to me.” The effect of it was of a naughty child thrusting out her tongue. “And you take your sanctimonious air right away to the Pontchartrain and drink too much and get into a dis-grace-ful fight, and get arrested, and break into print good. I s’pose,” she said, thoughtfully, “you were jealous—afraid I might steal some advertising and crowd you out.”

Potter laughed, a good, whole-hearted, boyish laugh. The sort of laugh one likes to hear. “It was funny, wasn’t it?” he said.

“Impertinent, I call it,” she said, sharply.

He laughed again. “If you want advice on any subject, you go to an expert, don’t you? Well, I’m an expert on breaking into print and getting myself talked about. My advice is worth something. I ought to charge for it.... Now there’s a notion. How would it do for me to open an office with a sign on the door, Expert Advice on Wild-oats Farming—Years of Experience?”

“You seem proud of it.”

“No, I’m not exactly proud of it. I’m not like little girls who do things for effect.”

She turned her back and marched to her ball, but before she was ready for the stroke she faced him again. “You’re just a naughty little boy throwing paper wads in school,” she said, sweetly, “and you think you’re a grown man being devilish.”

“Eh?” he said, a bit startled. On the face of it she had merely uttered a saucy, childish gibe, but Potter was struck by it. He tucked it away in his mind for future reference. There were elements of shrewdness, of insight, of truth in it.

“I have a puppy who chewed up my best slippers—because he hadn’t anything else to do,” she said.

“Do your friends, by any chance, hint that your tongue is sharp?” he asked.

She made no reply, but her driver whistled viciously through the air in a practice stroke.

“I’ll tell you what,” he said, “just to show you I’m forgiving I’ll let you play around with me.”

She looked at him an instant. “I’ll give you a stroke a hole,” she said.

“Eh?”

“I’ve seen you play,” she said, calmly.

“Drive,” he said, with a chuckle. “I ought to put up a cup, oughtn’t I?”

“Make it a ride in that aeroplane thing of yours,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to see how it felt to fly. Not just go up and come down, but a regular fly.”

“Not a chance. Your father would assassinate me.”

“You haven’t much confidence in your game, have you? To beat a girl who gives you a stroke a hole.”

“We’d both break into print. Can’t you see it in type? ‘Hildegarde von Essen explores the firmament with Potter Waite,’ with some account of your career with number of fines for speeding, and references to myself. Not nice.”

“Fiddlesticks! We shouldn’t have to invite any reporters....”

“But they’d hear about it. They always do.”

“A stroke a hole,” she jeered.

“Very well. Give me a beating and I’ll take you flying.” He felt confident enough, for he played a fair game of golf.

His confidence decreased after the first hole was played. He outdrove her and had the distance of her, but her every stroke was down the center of the course; she never overestimated her strength, and avoided trouble. On the green she holed a twelve-foot putt—and the hole was hers.

He settled down to play his best. The thing became not merely a game of golf between a man and a girl. It seemed to him that more was at stake than victory or defeat in a pastime. He became interested, intensely interested. He wanted to win and he played to win.... And he watched the girl. She interested him. She was so utterly natural, so without pose, yet so very different from the ordinary run of girls, particularly nineteen-year-old girls. There was a tang about her. It was as if one were eating bread and all unexpectedly encountered some unidentified, some palate-intriguing spice. That defined her for Potter. If he had been going to describe her he would have said she was highly spiced.

Potter played better than usual, but at the end of the ninth hole he was two down. They had talked little. Now she sat down.

“Tired?” he asked.

“Not the least,” she said, “but I find I play the last nine better if I sit here a few minutes and get the first nine out of my mind.... Had you any friends on the Lusitania?” She asked the question suddenly.

“Yes,” he said.

“If I were a man—”

“If you were a man—?” he repeated after her.

“I’d enlist. I wouldn’t wait for this country to go to war. I’d go across. A good many boys have gone, haven’t they? I’d go across and be an aviator—or anything they’d let me be....”

“For the Allies? I took it for granted you would be on the other side of the fence.”

“Pro-German!” Her eyes flashed. “I leave that for Father and his cronies. I believe they celebrated last night—actually. My mother wasn’t German,” she said. Potter knew Mrs. von Essen had died two years before. “I know Germans,” she said, presently. “I ought to; I’ve lived among them all my life.... Sometimes I think the whole race is a button short.” Potter was to learn that in her vocabulary “a button short” meant not quite complete mentally. “I like some of them, and I’d even trust some of them, but most of them are arrogant beasts.... I’ve read their books,” she said. “Dad has a lot of them. People used to think they were nice, slow, harmless, fat, good-natured. Maybe some of them are. But I believe that’s what the German government wanted the world to think.” These were unusual words to hear falling from a girl’s lips. She had been thinking. Perhaps that had happened in her life which made her think. “Will we declare war?” she asked, in her sudden way.

“Last night I was sure we would. To-day I’m almost as sure we won’t.”

She nodded. “People don’t realize.... But we’ll be in it,” she said. “No matter how much we try to stay out, they’ll force us in. They’ll sink another Lusitania and another and another, until we have to come in. You’ll see.... Partly because they don’t understand—and partly because that’s the kind they are. You know a German never understands anybody but a German. They can’t. Just before Mother died she said to me, ‘Garde’—she always called me Garde—‘don’t marry a German, honey. Nobody but a German woman should marry a German.’ And Mother ought to know, oughtn’t she? I’d rather marry a Chinaman,” she said, suddenly becoming girlish again.

“If we have war, what will all the Germans in this country do?”

“Talk loudly till war is declared. Then shut up and do sneaky things. Nothing in the open.... I think,” she said, slowly, evidently trying to set aside prejudice and cling to fact—“I think most of them will be loyal. In spite of their talk, I don’t believe most of them would care to live in Germany and in German conditions. That’s why. But there’ll be enough.” She got up quickly and teed her ball. “Let’s go on,” she said.

Hildegarde played the same steady game as before; Potter’s mind was on other things. Somehow he believed this girl was right; that she read the future truly. The sinking of the Lusitania meant war—sooner or later it meant war.... And the country was unready for war. It did not want to get ready for war.... She had spoken about going across to fight with the Allies. He considered that. It was a thing he was to consider for days and weeks to come. But that was a makeshift. He realized it was a makeshift. There must be something better, something more logical than that.

He won a hole and halved a hole in the last nine.

“When do we fly?” she asked, eagerly.

“I shouldn’t have promised.”

“But you did.”

He nodded. “Whenever you wish.”

“Let’s see. Suppose we say next Tuesday.”

“My car is here. Can I drive you home?” he said.

“I was to telephone for my car. Yes, you may.”

A limousine was just entering the grounds of the von Essen place in Grossepoint when Potter and Hildegarde reached the drive.

“There’s Father,” she said, and her lips compressed a trifle.

A big man who looked not unlike Bismarck, and who endeavored to heighten the likeness, alighted and stood beside the car, looking toward them. It was obvious he was waiting for them. Potter stopped his car and lifted his cap. Herman von Essen scowled.

“Since when are you friends with this young man?” he demanded. “Out of that car and into the house. Have you no sense—to be seen in public with this man whose picture is in the papers? For a girl to be with him is to lose her reputation.... And you”—he turned on Potter furiously—“take your car out of my grounds. Never speak with my daughter again. Do you hear? You are a drunken young ruffian.” He launched himself into a tirade of great circumstantiality.

Potter’s eyes were dark with the brooding expression which his friends counted a signal of danger, but he remained motionless, save to turn toward Hildegarde.

“I am sorry, Miss von Essen,” he said. “I shouldn’t have brought you. I might have foreseen—”

She smiled. It was not a bright smile, but a reckless smile, as reckless as one of Potter’s own might be.

“Thank you for coming.... I hope we shall be friends.” She did not glance at her father, but walked erectly up the steps and disappeared in the house. Von Essen continued verbally to chastise Potter, who did not look at him. Perhaps he did not dare, fearing the weakness of his self-restraint. The young man threw his car into gear and moved away, leaving von Essen gesticulating behind him.

He drove to his own house, a mile beyond. Before he reached there the brooding darkness was gone from his eyes; they twinkled. He was thinking of Hildegarde.

Detroit was flying high; it was spending as few cities have ever spent. Wealth poured in upon her, and men who, ten years before, had worried when they heard their landlady’s step on the stairs were building palaces in the midst of grounds for which they paid fabulous sums for each foot of frontage. No clerk or school-teacher was too poor to own a lot in a subdivision, laid out with sidewalks and shade trees, miles beyond the city’s limits. Overnight land increased in value, so that fortunate ones who paid ten dollars down on a lot sold their equities within the month at profits of hundreds of dollars. Men bought distant pasture-land for a song and sold it for an opera. The streets were full of tales of this man who had made a hundred thousand dollars, of that man who had cleared sixty thousand, of men by the dozens whose bank-accounts had increased more modestly, but still by thousands. Land that had gone begging at ten dollars a foot was eagerly sought at a hundred dollars.... This was a by-product of that great manufactory of wealth, the automobile.

As for it, and its growing sister, munitions, one believed whatever was told, and the tale fell short of the truth. One manufacturer filled the banks with his deposits, and, when they refused to accept more, was obliged to build his own bank.

When money flows in torrentially it washes away walls of economy. Detroit spent as it earned—lavishly. It was just completing what is perhaps the most magnificent clubhouse in the United States—a million-dollar plaything, the money for which had been raised almost in an hour. It was the new Detroit Athletic Club, outgrowth of that historic and honorable old athletic club which had so long been a landmark on Woodward Avenue when land was cheap and a quarter-mile cinder track and football-field might be maintained in the heart of the city. Five thousand men were found instantly who could afford this luxury.

Magnificent new hotels sprang up miraculously; department stores, surprised in their inadequacy by the multiplication of population, were adding annexes treble the size of the original stores. Everybody owned a motor-car.... The cabaret moved westward and found a welcome in a town once famous for its staidness. The handling of motor traffic became a greater problem for the police than the protection of the city from crime. And yet people scarcely realized what was happening. They took it as a matter of course—and flew high with the city.

Across the ocean another type of highflyer was coming into prominence. One might say the war had passed through its second phase. The first phase was the phase of fighting-men, of armies, of obtaining soldiers with rifles. The second phase was the artillery phase, the high-explosive phase. Each for its months filled the papers and demanded the interest of the world.... Now was approaching the third, the aeroplane phase. It was beginning to overshadow the other two in public estimation. Aeroplanes were no longer contraptions which one went to the country fair to watch performing tricks. They had come into their own. They ranked as a necessity. They had emerged from the cloud of obscurity which hung low over the battle-fields, and men were made to realize that victory in the air meant victory in the fields below....

Potter Waite had thought much of this, had hoped for it, had even ventured to prophesy it. One might say he was deeply interested in highflying of both sorts.

A certain fascination which mechanics held for him since childhood had enabled Potter to finish a turbulent college career with a mechanical-engineering degree. This, or what it represented, he had never put to use except in the way of a pastime. But aeronautics interested him. He was so fortunate as to be rich enough to play with aeroplanes, to fly aeroplanes, to own and experiment with aeroplanes, and there was something about the risk of it, the romance of it, the thrill of it, the novelty and the miracle of it, that fitted well into the recklessness of his unsatisfied nature. So he had been one of the country’s earliest amateur aviators. The part taken by the aeroplane in the Great War had quickened that interest, solidified it. It had become something more than the fad of a rich young man to him.

It was during the week that followed the sinking of the Lusitania that Potter was introduced to a Major Craig, of that then comparatively unknown branch of the United States military machinery known as the Signal Corps. It was at the Country Club, and Potter, who was seldom drawn to an individual, felt something much akin to boyish admiration for the slender, trim, uniformed figure of the young major. Craig was young for a major. He might have been forty, but a well-spent man’s life made him appear younger. He had not the face we have taken as typical of our soldier, but rather the softer, gentler features of the enthusiast—not the sharp, hungry look of the fanatic. He was a man with one compelling interest in life, a man bound to his profession, not by duty, but by love. Something of this was apparent at a glance. It became plain upon acquaintance. There was something about him—not the uniform he wore—but a subtle characteristic which set him apart from the run of men. He was distinct. After half an hour’s chat with him Potter perceived that the major was something wholly outside his experience, and he was interested. He was interested in the major’s conversation, in his appearance, but chiefly in that peculiar something which made Craig different from La Mothe or Kraemer or O’Mera. The others who had gathered about the table wandered off upon the links and left Potter and the major alone.

“You are the Potter Waite who has done something in the flying way, are you not?” asked the major.

“A little.”

“I wish,” said the major, enthusiasm fighting in his eyes, “that there were ten thousand of you.”

“There are people around this town,” Potter said, laughingly, “who wish there were one less.”

The major did not join in Potter’s laugh, but regarded the young man shrewdly, appraisingly—with something of sympathy and understanding in his eyes. He got to his feet abruptly. “I should be obliged, Mr. Waite,” he said, “if you would play around with me.”

Presently they were equipped and walking toward the first tee.

“Mr. Waite,” said the major, “have you ever considered the possibility that this country might be compelled to enter the war?”

“Yes,” said Potter, and the major saw that darkening of his eyes, that sullen, restless, forbidding expression which came at times over the boy’s face.

The major laid his hand on Potter’s arm. “You have been disappointed in us, is that it? You thought the country would flare into righteous rage over the Lusitania and go knight-erranting? Is that it?”

“Didn’t you?” Potter countered, a bit sharply.

“I am not permitted to express opinions,” said the major, simply. “You wanted immediate war because you are young and easily moved. Perhaps because you have not thought deeply what war means. I take it you are impulsive.... Have you asked yourself why you want war? Was it mere resentment? That isn’t an excuse for war. Was it the adventure of it? Or was it possibly something bigger and deeper? What do you think of the United States, anyhow?”

Potter did not reply immediately. What did he think about the United States? He did not know. As a matter of fact, he had done very little thinking about the United States; had rather taken the United States for granted. Somehow he felt embarrassed by the question.

“Do you perhaps love your country?” asked the major.

From another man Potter might have regarded this question as a symptom of mawkish sentimentality. From the major it seemed natural, unaffected, as if the major had the right to ask such a question and have a plain answer. Craig waited for Potter to answer, his face grave, gentle; his bearing sympathetic. Potter felt the sympathy, felt that he and this officer could grow to be friends.

“Why,” said Potter, presently, “I don’t know.”

The major nodded his head. “I’m afraid that’s the way with most of us—we don’t know. We’re thinking about ourselves and our businesses and about making money and passing the time. We have grown unconscious of the country just as we are unconscious of the air we breathe. That’s hardly a state of mind to carry us into war, is it?”

“No,” said Potter.

“Because war requires love of country,” said the major. “Not the love of country that orators talk about on July Fourth, but the kind of love that is willing to prove itself. War, Mr. Waite, means sacrifices such as we do not even dream of. It means that love of country must take place over everything else. Not a stingy loyalty, but a real love—the sort that gives life and everything one possesses to the country. Mr. Waite, if we should go to war to-morrow and your country should come to you and say, ‘I want your life. I want everything you possess in the world—wealth, comfort, place. I need everything to win this war,’ what would you say? Would you give willingly and gladly? I mean what I say literally.”

Potter stopped and faced his companion a moment in silence. “Could you?” he asked.

“I think I could,” said Craig. “I think my country means all that to me.”

“Why?”

“That you will have to find out for yourself. I can’t teach you patriotism, love of country, in half an hour, nor in a course of twenty lessons. I couldn’t teach you to love a woman. Each man must find those things for himself.”

“I suppose so,” said Potter, uneasily, and they walked along together in silence.

“We’ve heard a great deal about military preparedness lately,” said the major, presently. “It’s in my mind that we need another sort of preparedness even more. There is such an emotion as patriotism, Mr. Waite, but it seems to be dormant in this people. A couple of generations of ease and prosperity and peace have lulled it to sleep. We have grown careless of our country, as we sometimes grow careless of our parents. But I believe patriotism is here—more than we need universal military training, more than we need artillery and ammunition and war-ships, we need its awakening. We can never have one sort of preparedness without the other.”

“I had never thought about it,” said Potter.

“Will you think about it, Mr. Waite? And when you have thought about it, see if you don’t find it demanding something of you.... Do you know that an army without aeroplanes is like a blind man in a duel with a man who sees? Think about that. I sha’n’t tell you how many ’planes we have, nor how many trained aviators. It would shock you.”

“I know something about that.”

“But have you realized that if events force us into this war we shall need, not hundreds of ’planes, but thousands—possibly twenty-five thousand?”

Potter was astonished at the number. “Really?” he asked.

“That many will be absolutely necessary, and the best and fastest ’planes that can be had. Where will we get twenty-five thousand of them?”

“God knows,” said Potter.

“Mr. Waite, the War Department is not sleeping. Will it surprise you to know that I came to Detroit solely to have this talk with you?”

“With me?”

“We know all about you, and about every other amateur aviator in the country. All about you,” the major repeated.

“I’m surprised you found it worth your while to come, then,” Potter said, with, a trace of bitterness.

“For instance,” said the major, “we know what happened in your Pontchartrain Hotel the night the Lusitania was sunk.”

Potter flushed angrily, but made no reply.

“The manner of it,” said the major, quietly, “was regrettable. The impulse behind it—and we looked for that impulse—was hoped to be something not regrettable. I came to find out that and other things. I have not come to offer advice, Mr. Waite, merely to get information valuable to our country.... Had you thought you might be valuable?”

“General opinion seems to hold the opposite view.”

It was the major’s turn to remain silent. He watched Potter’s face keenly.

“What do you want of me?” Potter asked, finally.

“What would you do if war came?” countered the major.

“Enlist, I suppose. As an aviator, if I could. I’ve been thinking of going to France, anyhow.”

“That’s adventure,” said the major. “And as for enlisting, would you be most valuable there or here—helping to produce those twenty-five thousand ’planes? Think that over.”

“Do you believe we shall be in it?” asked Potter.

“I don’t know,” said the major. “But I do know that the man who goes ahead as if he were sure we shall will be doing the thing he should do. You, for instance, might think aeroplanes, plan aeroplanes, dream aeroplanes—fighting-’planes.... Shall we play around now?”

They played around, for the most part in silence, for Potter was following the major’s direction to think. In the locker-room and in the shower-baths they did not allude to the matter of their conversation, and when they came out on the piazza of the club they found themselves in the midst of a party of younger members talking the sort of talk that is generally to be heard on country-club piazzas and drinking as if that were the business of their lives.

“Hey, Potter,” called Jack Eldredge, “come over here and meet a pilgrim and a stranger—also state your preference.”

The major touched Potter’s shoulder. “Think it all over,” he said, and turned away.

Potter walked to Eldredge’s table, and Jack presented him to a young man in his early thirties who stood up and shook Potter’s hand warmly.

“Mr. Cantor, Mr. Waite,” said Jack. “Mr. Cantor came this morning from New York. Friend of the Mallards and the Keenes. Goin’ to be around Detroit quite some time—so I put him up here, of course.”

“Mr. Eldredge was very kind indeed,” said Cantor. “I have hoped to meet you, Mr. Waite. I have letters to you from Mr. Welliver and Mr. Brevoort.”

They sat down and Potter observed the stranger. He was dark, smooth of face save for a carefully shaped, slender mustache. His features were rather thin, but quick with intelligence. There was a hint of military training in his shoulders. It appeared he had recently come from abroad, and soon was talking fluently and entertainingly about his experiences on the fringe of the zone of war. Potter wondered what his nationality might be. At first he fancied the accent was of Cambridge, but there was another hint of accent underlaying the careful enunciation of the Cambridge man. Potter made the guess that Cantor had been born to some tongue other than English, but had, probably, been educated in one of the English universities. This supposition was proved later to be correct.

“I represent an investment syndicate,” said Cantor to Potter, presently. “They have sent me over to study the situation here, particularly the automobile industry. I seem to have come to the place to do that thoroughly,” he added, with an attractive smile.

“Detroit suffers with the automobile-manufacturing habit. There’s no cure,” said Eldredge.

“What a fascinating location your city has, Mr. Waite!” said Cantor. “I call to mind no other great city situated directly upon an international boundary-line. You sit in your offices and look into foreign territory—but I presume you are so accustomed to it that you seldom give it a thought.”

“Somehow,” said Potter, “we don’t think of Canada as foreign.”

“No,” said Cantor, “but I can conceive of circumstances which would compel you to think of it as foreign. I understand your government is irritated by certain British actions with regard to your mails and shipping. Might not something disagreeable grow out of that?”

“It might. These are puzzling days, Mr. Cantor. I confess I am bewildered by them. Impossible events happen with startling ease, and inevitable consequences fail to follow amazingly. Yes, I can imagine trouble coming with Great Britain, but somehow it does seem unlikely as long as Germany lays a murder on every mail-bag England plays. You aren’t especially apt to bother with a man who jostles you in a crowd if there is another man trying to hit you with an ax.”

Cantor half shut his eyes and peered into his glass. Presently he looked up to Potter and nodded. “I get your point of view,” he said. “I wonder how many people share it.”

“I’ve given up guessing what the people think.”

“It wouldn’t surprise me to see your public opinion veering to favor Germany.”

“Some of our public opinion does favor it. Our German-Americans and such like.”

“A good many of them—millions I understand.”

“Yes.”

“Perhaps capable of influencing a majority?”

“I don’t know,” said Potter, and nodded his head, not exactly with satisfaction, but as a man does who fancies he has made a point in an argument. “German public opinion here seems to be organized,” said Potter.

“The German government is efficient. If it has felt the need of fostering your favorable opinion, I think we may say it has taken steps to foster it.”

Potter wondered just where Cantor stood in the matter, but the courteous air of the man, his manner of putting a question, were not those of a man holding to one opinion or the other, but of a seeker after information. He asked questions, but answered none, not even by the expression of his face. He had made no direct statement; had shown neither pleasure nor displeasure with what he had heard. Yet Potter judged him to be a man capable of strong opinions and of taking action in support of them. There was nothing neutral about the man. He was positive, but baffling. He was an individual who would play his cards on the merits of his own hand, Potter thought, and would carry his betting just as far as the value of his cards warranted. Until that point arrived he would not lay down his hand. Potter determined to see what a direct question would produce.

“What do you think of the sinking of the Lusitania?” he asked, abruptly.

Cantor regarded him for an instant with the air of a man who wishes to use care to express himself clearly, and then he replied with such a manner of clarity as made Potter chuckle inwardly.

“The sinking of the Lusitania,” he said, with the positiveness of a man stating an incontrovertible fact, “is a matter without precedent. It is my firm opinion that the German Admiralty considered carefully every effect which might derive from it before ordering the act.”

An ironic rejoinder occurred to Potter—a rejoinder which he would have made regardless of courtesy had his unlovable mood been upon him—but he withheld it now, contenting himself with a smile which Cantor read correctly and answered with a twinkle of his clear eyes. Potter knew that Cantor had weighed his intention to draw a positive statement and rather enjoyed the knowledge that Potter understood fully his evasion of it.

The conversation turned to less momentous affairs, but it seemed as if Cantor could not express fully his admiration for Detroit and for its location. He spoke of the Lakes, of the millions of tons of ore and millions of bushels of wheat traveling past Detroit’s door in the holds of mighty vessels; of vessels which carried northward cargoes of coal to a region where coal was a necessity. He referred to the carriage of passengers by water on steamers of a size and luxury which the stranger perceived with amazement on an inland waterway. He had a word to say about the ship-canals at Sault Sainte Marie and the Welland, and of that minor canal at the mouth of the River St. Clair. Eldredge told him something of the new channel constructed in American waters across Lime Kiln Crossing and Bar Point Shoals below the city, and described how engineers had constructed the mightiest coffer dam in the history of engineering; how they had built dikes miles in length to hold out the waters of the river, pumped dry the areas between, and then sawed their channel out of the dry rock. Cantor was fascinated by it all.

“But,” said he, “those are points of danger, are they not? Suppose that war with England should arrive. Would not your Eastern steel-mills, upon which you must depend for the manufacture of ordnance and munitions, be left helpless if one of these gateways from lake to lake should be closed? Imagine the destruction of the locks at the Soo, for instance? Are they well guarded?”

“Probably,” said Potter, “there is an aged constable with a tin star within calling distance.”

“It is a splendid thing for a country to have the feeling of security that yours holds,” said Cantor, with open admiration that Potter felt, but could not identify, to be derisive.

“Why should we guard them?” Eldredge asked. “We aren’t fighting anybody. Besides, an army never could get to them.”

Potter shot a glance at Eldredge which was tipped with contempt, and Cantor intercepted it and smiled at Potter as one man smiles who shares a bit of humor with another. It was as much as to say, “You and I have more common sense than to say that, haven’t we?”

Cantor drew the conversation away from war again. “You play golf here frequently?” he asked Potter.

“As often as I can manage it.”

“I play a duffer’s game myself, but I hope you will take me on some day. They tell me you are above the average. I shall enjoy watching you—and possibly can pick up some pointers. My approach is miserable—miserable.”

“Easiest stroke in the bag,” said Eldredge.

“No doubt, but there is no easiest stroke for me. In my case they are all difficult, with some worse than the rest.”

“Glad to go around with you any time,” said Potter, and Cantor made it apparent that he was really gratified. He had abilities that way, a manner which seemed, without effusiveness, to express admiration; to show that he was most favorably impressed by a companion.

Either the man was naturally affable or he had set himself with purpose to make friends of those in whose company he found himself at that moment, Potter decided. As for Potter, he did not enter into the conversation, but sat back listening and thinking. Without setting himself deliberately to do so, he studied Mr. Cantor, and was compelled to the conclusion that the stranger was an exceptionally brilliant man; not only that, but a man of personality, dominating personality. The others of the party appeared colorless when set against him. Potter wondered if he himself seemed as colorless as they.

Potter was one who liked or disliked swiftly. Usually, on meeting an individual, he determined instantly and almost automatically whether or not he cared to continue the acquaintance and to admit the stranger to fellowship. He found himself unable to make up his mind about Cantor. That gentleman was too complex to make the judgment of him a matter of a word and a glance.

Potter was disturbed and uneasy. The atmosphere of the club piazza irritated him this afternoon. He could not enter into the spirit of the effort to make dragging time pass endurably, which was the profession of most of the men present. Major Craig had surprised him, had increased the restlessness, the dissatisfaction which so frequently possessed him, and he wanted to go away alone to carry out the major’s direction to think. He got up suddenly.

“I’m off,” he said. “Hope I shall see more of you, Mr. Cantor.”

“I should like to call as soon as convenient,” said Cantor, “to present my letters.”

“We don’t go much on letters of introduction out here,” Potter said, smiling. “A letter of introduction never made anybody like a man he didn’t cotton to, nor dislike a man he took a liking to. Call when you like, and don’t bother with the letters.”

Cantor laughed. “Perhaps you’re right. But I’ve always believed that a man coming to a strange place should come well introduced, if he can. People are suspicious of strangers. I have provided myself with letters because it is important to me that there should be no uncertainties about me.”

“Bring them along, then,” said Potter, who was by nature unfitted to understand how anybody could care much what strangers or acquaintances thought of him.

Potter walked to his car, and in a moment was driving toward the street. A runabout which he recognized at once turned into the grounds and a glance showed him Hildegarde von Essen was driving. She saw him at the same instant, and lifted her hand, drawing over to the side of the drive and stopping. He drew up beside her.

“To-morrow’s Tuesday,” she said.

“Now look here, Miss von Essen, your father—”

“My father’s aunt’s rheumatism!” she said. “Father’s in New York, and you promised.”

“I know I promised, but in the circumstances you ought to let me off. He didn’t exactly welcome me with open arms, and the Lord only knows what he’d do if I took you flying.”

“You promised,” she repeated, stubbornly.

“I know,” he said, with the elaborate pretense of patience one shows to a difficult child, “but—”

“And I’m not afraid of father. To-morrow morning? I’ll be ready as early as you like.”

“Nine-thirty, then,” he said, helplessly, “at the hangar.”

She beamed on him. “You’re a duck, Mr. Waite,” she said, “and I’ll not let father hurt you.”

She drove on and left him looking after her. What a flamelike little thing she was, he thought. What he did not think was—how like she was to himself; how her restlessness matched his; how her recklessness and his recklessness were cut off the same piece. And she was charming in an exciting sort of way. “If she ever cuts loose—” he said to himself.