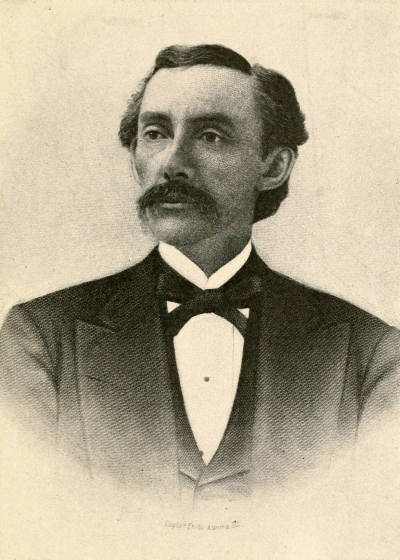

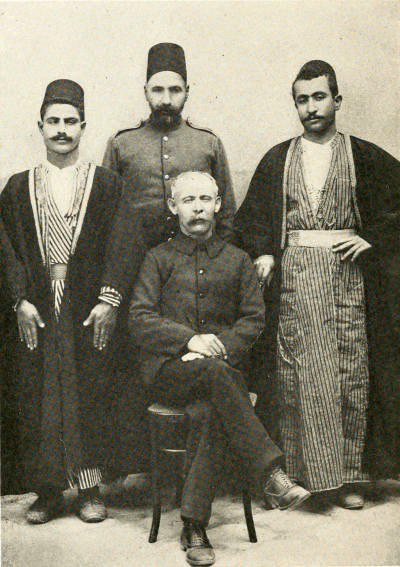

MERRICK RICHARDSON AT THE AGE OF SEVENTY-FIVE.

LOOKING BACK

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

By

Merrick Abner Richardson

AUTHOR OF

"JIM HALL AND THE RICHARDSONS", "EIGHT DAYS OUT", "MINA FAUST",

"ROSE LIND", "PERSONALITY OF THE SOUL", "CHICAGO'S

BLACK SHEEP", "TWILIGHT REFLECTIONS."

Privately Printed

CHICAGO: MCMXVII

Copyright 1917

By

Merrick Abner Richardson

PREFACE

My spare time, only, is occupied in literary efforts. I never allow them to interfere with either my business or social life.

In composing, in a mysterious way, I comprehend the companionship of my imaginary friends as vividly as I do the material associates of life. To me imagination is the counterpart or result of inspiration, while inspiration is light thrown upon the unrevealed. The image may be the result of known or unknown cause, but the mystery does not blot out the actual existence of the image. The material image we call sight, the retained memory, and the unknown revelation, but all are comprehensive images.

I see a bird, its form created a picture on my eye, the image of which mysteriously remained after the object had disappeared. Now what or who cognizes the primitive object, the formed picture or the retained image?

The materialist assumes he has solved the mystery when he says; The appearance of the object formed an impression on your brain; omitting the important part of who comprehends the impression.

These material and spiritual views are not the two extremes, there is no midway, one is right and the other is wrong. Either man is a spiritual, responsible being or he is just temporary mud.

Therefore imagination, to me is incomprehensible realization, while materialism is the symbol of passing[ii] events. This explains how my imaginary friends become so dear to me.

The ideas presented in my story of Mary Magdalene I gained through descriptions conveyed to me by Jona while traveling across the Syrian desert. He always began in the middle of his story and worked out both ways, which made it difficult to take notes, besides at the best it was but a legend, dim and indistinct.

In this work I have carefully avoided Oriental style, language or customs for two reasons: First, there is not an Oriental scholar now, who could do them justice, Second, one is perfectly safe in bringing any people of any age right down to our times. For, the culture of one tribe or race does not influence incoming souls for the next generation. The human family enter life on about the same plane. A child from the low tribes of the jungles or from the desert wild, if brought up by a Chicago mother, might become as great as one of the royal family. The feelings, aspirations, sorrows and love of Mary Magdalene and Peter were similar to what ours would have been under the same conditions. Therefore I bring the story of Magdalene right down to yesterday.

I first constructed the story of Magdalene while in Jerusalem, then I revised it in Egypt, and have been revising it at intervals ever since. From Jona's continued reiteration regarding her prepossessing gifts, spiritual and unwavering qualities, especially her firmness before Caiaphas, I formed her personality in my mind and associated her with bright women of today, then I let Magdalene talk for herself.

To me she was no exception from the women I associated with in Chicago. There are not wanting women in Oak Park who under the same circumstances would[iii] have followed Jesus to Jerusalem, disdained to deny him and would have pleaded before the sanhedrim at the dead of night to have saved their associate from the misguided servants of the devil.

The reminiscenses of the pioneer Richardsons, Jim and Winnie, Sunshine days around Wabbaquassett, John Brown, roving escapades of the Richardson Brothers, my athletic exploits, my travels and other scenes of my life are primitive truths copied from memory and set forth in my original form of expression.

My attack on materialists or infidelic instructors stands on its own feet and opposes a tendency that will create degeneracy if continued.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| My Ancestors | 9 |

| Woburn | 10 |

| Traditions | 12 |

| Records | 15 |

| Old Homestead | 17 |

| Jim Hall | 19 |

| Love Spats | 20 |

| Jim's Story | 31 |

| The Arrest | 35 |

| The Martyrs | 37 |

| The Escape | 38 |

| Stubbs' Store | 40 |

| Susan Beaver | 45 |

| Revenge | 49 |

| Alone in the Wilderness | 51 |

| Hunting for Baby | 54 |

| Muldoon | 57 |

| Our Wabbaquassett Mountain Home | 61 |

| Woodchuck in the Wall | 64 |

| Sunday Morning | 69 |

| Husking Bee | 76 |

| Prayer Meeting at Uncle Sam's | 78 |

| Golden Days | 81 |

| The Wild Sexton Steer | 83 |

| School Days | 87 |

| Country Boys in Town | 89 |

| As a Yankee Tin Peddler | 94 |

| The Thompson Family | 97 |

| John Brown | 99 |

| The Dead Appear | 106 |

| Vida's Daring Exploit | 108 |

| Owen Brown's Story | 110 |

| After the Mist Had Cleared Away | 115 |

| Yankee Horsemen Go West | 117 |

| My Relation | 121 |

| Horse Jockies | 123 |

| Landed in Chicago | 126 |

| Dr. Thomas | 128 |

| Early Chicago | 131 |

| Horse Racing in Chicago | 134 |

| [vi]Hopeful and Rarus | 137 |

| Chicago Piety | 141 |

| Public Conveyance | 143 |

| My Athletic Exploits | 146 |

| My First Hundred Mile Run | 148 |

| Arthur's and Walton's Long Run | 151 |

| The First Century Race | 157 |

| Dead Glacier | 160 |

| Miraculous Escape From a Bear | 168 |

| My Education | 173 |

| Hawaiian Islands | 176 |

| South Sea Islands and Australia | 180 |

| New Guinea | 183 |

| Cochin China | 190 |

| Mesopotamia | 192 |

| Rud Hurner | 193 |

| Off for Babylon | 198 |

| On the Euphrates | 200 |

| On the Shat-el-chebar | 201 |

| Koofa, Arabia | 203 |

| The Sheik of Koofa | 205 |

| Wild, Yet Beautiful | 209 |

| Nazzip | 211 |

| The Man I Had Seen Before | 212 |

| Real Bedouins After Us | 214 |

| Suspicion Aroused | 217 |

| The Rechabites | 221 |

| Sleeping Beauty of the Desert | 225 |

| The Abandoned Castle | 227 |

| Mary Magdalene | 229 |

| Dina of Endor | 231 |

| The Home of Magdalene | 235 |

| John and Magdalene | 237 |

| Ruth | 240 |

| Darkness Over Galilee | 242 |

| Surprise for the Pharisees | 248 |

| Council of the Disciples | 251 |

| Turn of the Tide | 253 |

| Magdalene's Heroic Plea | 255 |

| Jesus Speaks | 261 |

| The Exodus | 262 |

| Waiting By the Jordan | 265 |

| In Council at Jericho | 267 |

| Arrival at Jerusalem | 270 |

| Adultery | 272 |

| Magdalene Pleading With Jesus | 278 |

| At the Home of Mary and Martha | 280 |

| [vii]A Naughty Maid | 282 |

| Lazarus Restored | 285 |

| Conspiracy to Murder Jesus | 287 |

| The Mob Fall Upon Jesus | 292 |

| Magdalene Before Caiaphas | 295 |

| Jesus Before Pilate | 300 |

| The Crucifixion | 302 |

| Alone on Olivet | 304 |

| Magdalene Herself Again | 307 |

| Ruth Comes to Meet Magdalene | 311 |

| Joseph's Last Interview | 312 |

| Magdalene's Last Night With John | 315 |

| Last Good-Bye | 321 |

| The Prickett Home | 324 |

| Ourselves | 326 |

| William James, of Harvard | 328 |

| Gladstone | 335 |

| Evening of My Life Day | 340 |

| Fifty-four Miles' Hike | 342 |

| Back Home | 348 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Facing Page |

|

| Merrick A. Richardson | i |

| Camp of the Stafford Pioneers | 14 |

| Ancient Cemetery of the Stafford Pioneers | 16 |

| Winnie Richardson | 21 |

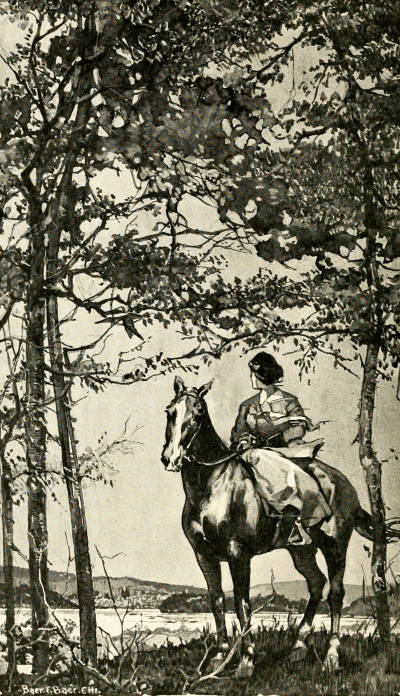

| Good Morning, Miss Richardson | 23 |

| Jim in the Woods | 52 |

| Our Mountain Home | 61 |

| Chasing for a Kiss | 76 |

| Prayer Meeting at Uncle Sam's | 80 |

| When the Folks Were Away | 84 |

| The Aborn Home | 86 |

| Wabbaquassett Girls | 88 |

| Charming Old Wabbaquassett | 90 |

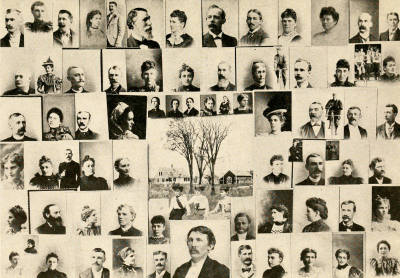

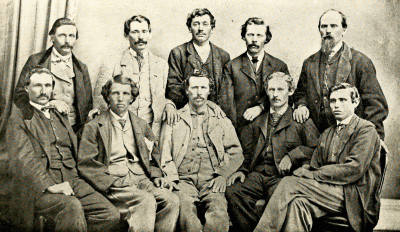

| Album of Sunny Days | 94 |

| Mary Jane Hoyt | 96 |

| John Brown, 1850 | 99 |

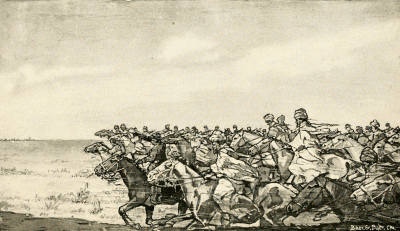

| Vida Thompson's Midnight Ride | 109 |

| Near John Brown's Adirondack Home | 115 |

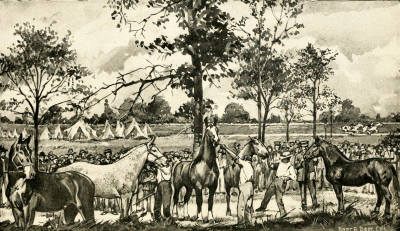

| Yankee Horsemen | 117 |

| Horse Sales | 123 |

| Dr. Thomas | 128 |

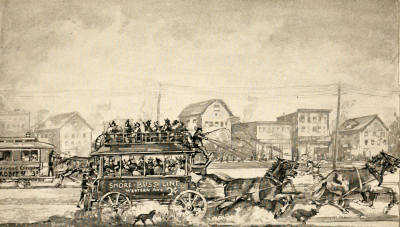

| Early Chicago | 142 |

| G. M. Richardson and Family | 144 |

| Saddle Horse Days | 148 |

| Cycling Run to South Park | 150 |

| North Shore, Loon Lake, Winona Grove | 152 |

| The Fox River Bicycle Race | 158 |

| Arthur Richardson and Friends | 164 |

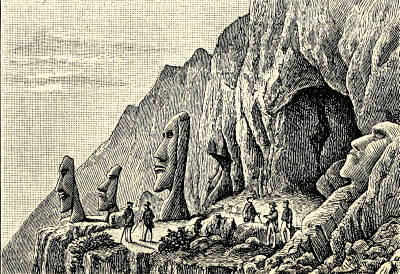

| Easter Island | 181 |

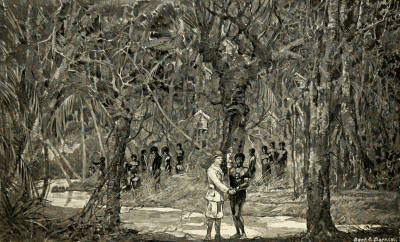

| New Guinea | 187 |

| Mesopotamia Servants | 193 |

| Desert Life Among the Arabs | 209 |

| Ruins of Tadmor | 227 |

| Mary Magdalene | 231 |

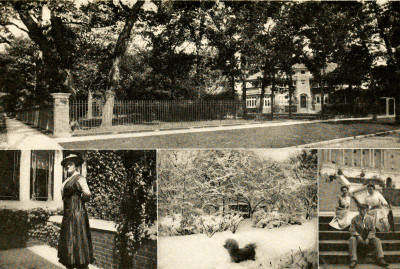

| Prickett Home | 324 |

| Arthur Richardson and His Twins | 336 |

| Our Oak Park Home | 338 |

| Fannie Peterson | 342 |

| Vida | 344 |

| Barbara Beaver | 346 |

| My Children | 349 |

LOOKING BACK

MY ANCESTORS

Ezekiel Richardson, with his wife Susanna, joined the Protestant Church in the Village of Charlestown, Mass.—now Boston—in 1630. The following year Thomas and Samuel Richardson joined the same church; the records of the will of Ezekiel prove them to have been his brothers.

When they came to New England, or where from, is unknown, but as about thirty ships of British emigrants came into Boston Harbor about that time, it is safe to assume that they came on one of these vessels, but possibly they may have come on one of the boats which followed the Mayflower nearly ten years previous.

It appears that there arose dissensions in the church and those good Pilgrim Fathers and Mothers strove among themselves until 1634, when the three Richardsons, with several other families, withdrew and decided to start a colony and a church of their own, where they could worship God in peace.

WOBURN

Through a swamp on the west, called Cat Bird Glen, ran a trout brook to the meadows below. Beyond this woodland glen lay an upland plain, held by the Indians as a camping ground, which the Richardsons concluded they might, through the persuasion of powder and bullets, be able to occupy and leave the parent church at Charlestown to mourn their departure.

Accordingly about twenty families, including the Richardsons, took possession of the site, dug their cellars, and built primitive homes together with a log church and named the town Woburn.

Joy mingled with pride encouraged the men to subdue the soil, hunt, snare and trap the game and fish, while the buxom dames hummed their spinning wheels as they cooed their frolicsome babies beneath the shadows of the great forest monarchs who seemed loath to give way to the encroaching steps of the white man.

Contrary to the general rule, that rats and ministers advance hand in hand with civilization, in this case the ministers failed to appear for the reason that the home church of England refused to recognize the seceders as children of God by turning down their supplication for a regular ordained preacher.

Here the true spirit and determination which seems to tinge the veins of the Richardsons made its first appearance. Ezekiel, by the grace of God, took upon himself the leadership in all the praying and singing of[11] the independent church for about ten years. He officiated at all weddings and funerals, besides established the whipping post for those who did not appear in church, with clean shirts on, three Sundays each month to hear him preach two long sermons, when it is said he often preached so loud that he could be distinctly heard in the Charlestown church two miles away, to the annoyance of his old-time associates.

After Ezekiel's thrifty swarm had become greater than the parent hive at Charlestown and the hand of time began pressing heavily upon his shoulders, a regularly ordained preacher was sent in, which the parishioners did not like as well as they did Ezekiel, for he could not clothe and feed himself as Ezekiel had done, but he stayed until he died, and here is a sample of primitive piety in our grandfather's days:

"The Reverend Mr. Carter of the Woburn Episcopal Church died, and being a good man, our forefathers decided to turn out in mass, give him a Christian burial and charge the expenses to the town. Of the itemized bill—coffin, shroud, grave-digging, and stimulants,—the latter, the liquor bill, exceeded all the other expenses."

See Woburn Town Records, Volume 3, page 68.

Thus while we find traces of weakness in our ancestors, a principle seems to have been involved which made New England a hot-bed for vags and tramps. No wonder we sigh for the good old days when respectable citizens did not have to lock their doors on Sunday, for all the thieves were in church.

TRADITIONS

Through the first appearance of the Richardsons in Charlestown we have an unbroken line of nine generations through Ezekiel of Woburn 1630 to Marvin of Chicago 1917.

Ezekiel of Woburn.

Theopolis of Woburn.

John of Stafford Street.

Uriah of Stafford Street.

John of Devil's Hop Yard.

Warren of Wabbaquassett Lake.

Merrick of Chicago.

Arthur of Chicago.

Marvin of Chicago.

Of course, my brothers and cousins perpetuate this name, the same as I do. Collins and Gordon, my brothers, with Orino, the son of my Uncle Orson, alone have raised about twenty boys.

The living male descendants of Ezekiel, Samuel and Thomas, who carry our name, must now be more than one hundred thousand Richardsons, and I presume few of them trace back their relation more than three generations, but they could if they would.

MY GRANDMOTHER'S STORY

My grandmother, Judith Burroughs Richardson, who died in 1859, age 94, seemed in the evening of her life-day[13] to think, dream and commune with her ancestors and friends, who long since entered Paradise, and now seemed to be throwing back kisses to loved ones approaching that land of delight.

From her experience and traditional reminiscences I here give a condensed sketch of her apparent and vivid memories:

James Burroughs, her grandfather, was the son of the minister, George Burroughs, her great-grandfather, who was hanged at Salem, Mass., August 19, 1692, for being in league with the devil.

James was arrested soon after, but escaped from Salem jail and, under the name of Jim Hall, lived in Connecticut for several years. Later, under his right name, he married Winnie Richardson, a Stafford Street girl, and they settled near Brattleborough, Vermont, where grandmother's father, Amos Burroughs, was born.

After James died, her grandmother Winnie came to West Stafford to live with them. She died before grandma was born and was buried in the family lot near their house. Her gravestone was still standing when my father was old enough to go with his grandfather Amos Burroughs and see them.

The homestead where Winnie died and grandmother was born and married can be found by following the south road out of West Stafford and turning the first road to the right, across the brook and up the hill to the first farm scene.

Winnie's father, Theopolis, son of Ezekiel, and several other men with their families, came West when she was a little girl and took possession, or squat, on the northern rise of a highland plain, where a grand view of[14] the far-away Western mountains can be seen. They called their camp Stafford.

John, Winnie's brother, who was conducting an Indian trading post at Medford came on later, with his two brothers, Gershom and Paul, and opened up the famous Stafford Street, which was laid out twenty rods wide and about two miles long, the southern terminus being about one mile northeast of Stafford Springs.

John Richardson took up the first farm at the north entrance on the west side and Silas Dean took the first on the left, or east, side from the old campus on the hill at the north end of the street.

All between the walls, which was later changed to sixteen rods, was commons. The church in the center was used for spiritual devotion, recorder office and court of justice.

ARRIVAL OF THE WOBURN PIONEERS AT STAFFORD STREET WHEN WINNIE RICHARDSON WAS TEN YEARS OF AGE. RECENT VIEW OF THE WESTERN HILLS FROM THE ORIGINAL CAMP.

RECORDS

The records of those New England pioneers are dim, as the Puritans considered church members only, as persons.

Boston records (Woburn), as we have seen, seem to extol Ezekiel.

Theopolis according to his will, must have been a financial success.

The Stafford Street records, I was informed by Mrs. Larned, who now lives on the old homestead, were kept in their family from the beginning until lately, when they became such a source of annoyance from ancestor seekers, like myself, that they sent them to the recorder's office at Stafford Springs.

At the recorder's office at Stafford Springs I found that John Richardson from Medford came to Stafford Street in 1726, this, though meager, acts as the official connecting link between Woburn and Stafford.

Another scrap I found was that Paul Richardson had taken land adjoining his brother, John Richardson, this identifies both John and Paul.

Regarding Gershom, the other one of the three brothers, I found this:

"Gershom Richardson, son of Gershom and Abigail, born in 1761."

This would make the elder Gershom Richardson contemporary with John and Paul.

E. Y. Fisk, an early settler, told me that a part of the early church records have been burned.

In the old graveyard just south of the brook which crosses Stafford Street still remains the headstone of Lot Dean, who died in 1818.

Lot would be of the next generation from Silas Dean, who took the farm opposite John Richardson.

Near the grave of Lot are the headstones of Uriah Richardson and his wife Miriam, who died October 18, 1785, at the age of 75. Uriah must have been all right, for Miriam, who died twenty years later, had had inscribed on his headstone:

"The memory of the just is blessed."

Grandmother remembered Uriah, the son of John and the father of John, her husband.

Now while the traditions, records and gravestones may prove each in themselves to be weak evidence, together they form an unbroken chain from Ezekiel down to our times.

ANCIENT CEMETERY OF THE STAFFORD STREET PIONEERS WHERE MOST OF THE GRAVE STONES ARE FOUND

BROKEN AND IN THE WALL WHICH IS BUILT AROUND THE LOT.

LEFT TO RIGHT. M. A. RICHARDSON. WALTER SKINNER. LUCIUS ABORN.

OLD HOMESTEAD

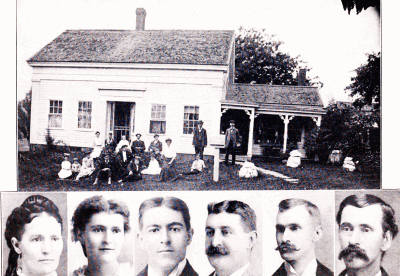

With my interesting nieces, Joe and Lina Newell, one bright summer day, I visited the ancient homes of the Stafford Street, Conn., Richardsons.

E. Y. Fisk and his son now possess the historical property. The son from Springfield, who was haying there at the time, invited us and all the other Richardson tribe to come and camp on the homestead grounds, sit on the old walls, gaze over the western mountains and even coquet with the star Venus evenings, all of which look now the same as when our ancestors saw them 200 years ago.

That day, July 19, 1916, with those girls, viewing the scenes and taking pictures of the surroundings, imprinted on my mind an oasis of beauty ever awaiting recall as I journey over the trackless sands of time.

The present seemed to pass away as the past unfolded its charms while we were reminded of the long ago.

Sacredly we listened to the voice of Mother Mary calling Winnie from the kitchen door, saw the men in homespun shirts and trousers coming up from the meadow below. Heard the careless boy whistling while unyoking the lazy oxen. Saw old dog Towser sleeping in the shade. And in the pasture far away we seemed to hear the faint tinkling of the cow bell on the brindle steer.

Day dreams, says one.

Imagination, says another.

May it not be that when death removes this earthly garment, we will again realize that the past, present, and future are one.

If the image of the face before me now is the retention of the face I saw yesterday, may not all fiction, invention and imagination be retention of occurences we can only recall in parts?

The power of recall is mysterious. If we dream of the dead as living when we know that they are dead, but we cannot recall that which we know, may we not know of pre-existence but lack the power to recall?

Thus Lina, Joe and myself spent a happy summer day on the New England hills, which we will pleasantly recall when the cold winds of winter rattle the doors and windows and we are hugging the radiators.

JIM HALL

During the days of the New England pioneers our early church had more trouble in evolutionizing Christianity from bigotry than in driving the red man from his native lair. Therefore, as the records show my ancestors to have been entangled in this muss, I have arranged, in this family record, and the story of my life, the story of Winnie and Jim.

One warm May evening, in 1693, a stranger, who said his name was James Hall, appeared at the door of Deacon Felker's home in Stafford, Conn., and applied for a job. His face betokened firmness, his speech was clear and distinct, while a tinge of sadness seemed to pervade his distant smile.

He claimed to be a good chopper and, as the deacon was now clearing up his future home in the New England wilderness, he soon bargained with Jim for all the season.

Hall soon became a favorite in the colony, broke all the unruly steers, saddled the ugly colts, collared Bill Jones, the terror of the town, and thrashed him soundly; but did not attend church until the influence of Winnie Richardson changed hatred to forgiveness.

LOVE SPATS

For some weeks the Felkers had had many callers, who sympathized deeply with the poor broken-hearted mother over her lost Juda among the Indians, but time, the blessed obliterator of all earthly troubles, soon brought forward other scenes and changes, and people laughed, joked and enjoyed themselves at Stafford as usual.

Winnie Richardson and her father were over to see the Felkers almost every day and Mr. Richardson would hear nothing about the pay for the colt which the Indians had stolen from Jim while searching for Juda, saying he had another one as nice, which, if Jim would come over and break, so Winnie could ride it, he would call it square.

One evening Winnie came over and, as was her custom, fluttered around and fussed over Jim, bandaging up his sore foot, which he had hurt during the hunt for Juda. Then she made tea for Mrs. Felker and slicked up the room, while Jim lay back in the chair and watched all her movements.

Jim felt almost like crying, he was so worn out and heart-broken over the loss of little Juda. Everyone knows how sweet home and friends seem under such circumstances; but here was Winnie, who had won his heart, and he wanted to tell her so, but she would not let him.

"Winnie," he said, in as a careless a manner as he was capable of, "you do not know how much that new gown becomes you."

WINNIE RICHARDSON, WAITING ON THE EASTERN BLUFFS OF OLD WABBAQUASSETT.

"Thanks, Jim, I'm glad you like it; do you know I have worked on it ever since you went away? I was so worried about you I had to work or ride old Dan, to keep from going wild. Several times I rode down to the Springs, followed the trail around the west bend way up to old Wabbaquassett, around to the eastern highlands from where I gazed across the pretty waves, hoping to see you coming, but saw only Nipmunk maidens sporting in their canoes."

"Then, if I had never come back, Winnie, I suppose you would have worked on that gown and ridden to Wabbaquassett Lake all the remainder of your life."

"I do not know. I know I wanted you to come home."

Jim was encouraged. This was more than she had ever said before, so he ventured to say, "Winnie, come here and give me your hand."

She came forward, and placing her hand in his, said, laughingly, "Well, Jim, what?"

"Now, Winnie, why were you worried for fear I would not come home and what did you want me to come back for?"

"Why, Jim, are you so simple as all that? You know that father expects you to break his colts in the spring, besides he thinks he cannot get along without your opinion on cabbages and turnips, then why would it not worry me? Now, Jim, I'm going home, and I want you to limp over tomorrow and see me, and stay all day, and we will have a good visit. But, really, Jim, you must not talk serious to me; you must give up that." Both were silent a moment and then she continued: "There, James Hall, has that little lecture almost killed you? I see you[22] have the dumps. That will never do. Look up here, Mr. Hall, have you forgotten that Miss Richardson is present?"

Jim looked up and endeavored to catch her eye, but no use. When she saw how pitiful he looked she burst out laughing and walked away with her chin way up high, then came back with a smile, bade him good-night, and she was gone.

Jim was in trouble. Mrs. Felker was delirious with grief. Little Juda, the sunshine of the home, was gone, and Winnie had told him plainly he must abandon all serious thoughts. He lay awake way into the night and formed his plans thus: "I will not go over to Richardsons in the morning, nor the next day nor the next, and perhaps never. I will take my axe and go up among the old hickory trees and work from sun to sun and try to banish little Juda from my mind, and also try to forget what a fool I am; fool—fool—of course I am, tossing around here all night over a girl that does not care for me. The idea of my consulting with her father over a cabbage patch. I think Jim Hall is not quite dead gone yet—no, I will not show my face there again very soon, of course not. Now I will turn over and go to sleep." But poor Jim, like many others, would like to forget his Winnie, but could not. Winnie had won his heart. She had come to stay.

Morning came and as the sun banished the dew from the grass, so daylight had upset all of Jim's plans concerning the hickory logs. He did not want to see Winnie in particular—no, but then he must not treat Mr. Richardson shabbily because Winnie had misused him. "Oh, I'll go over, of course I will, and visit the old folks, and if I see her I will pass the time of day to her—that is all."

GOOD MORNING, MISS RICHARDSON!

He found the old gent out feeding pigs and soon they were engaged in a friendly conversation. When they turned into the house, Aunt Mary came briskly forward to greet him and asked many questions concerning his long hunt for Juda among the Indians, which he could have answered more sensibly had he not been expecting Winnie. Of course, he was not anxious to see her, but he wondered where she was.

"Jim," said Mr. Richardson, "you will find plenty of those early apples down in the orchard if you care for them." So Mr. Hall started through the orchard and came spat upon Winnie by the wild rose bush, on the orchard wall.

"Good morning, Miss Richardson," he said, as he extended his hand in a cold businesslike manner.

Winnie paid no attention to his good morning, but brushing aside his extended hand she began fixing a white rose in the buttonhole of his coat as she said in a soft tone: "Jim, how would you feel if you were a girl and had gone and primed yourself all up nice so as to look sweet as possible, waiting for your fellow to come and say, 'Hello, Winnie, how sweet you look this morning!' but instead to see him come stalking through the trees as though he was monarch of all he surveyed, saying 'good morning, Miss Richardson.' Now, own up, Jim, that you deliberately planned that scheme to frighten me."

"Well, but you see, my dear."

"Yes, Jim, I see. I know all about it. You have been nerving yourself up to show that you did not care for me. You did it nicely. I thought you could not hold out more than a minute, but I think you did about two. And[24] now you're smiling, calling me dear, and will not let go of my hand. You did not sleep well last night, did you?"

"No, I did not."

"Was Mrs. Felker nervous?"

"Yes, she did not sleep a wink before two o'clock."

"And how about Frank?"

"Oh, he always sleeps like a log."

"Say, Jim, why do you take such an interest in Frank; where did the Felkers get him?"

"Boston, or somewhere East."

"What is his name?"

"Burroughs, they say."

"Burroughs—Burroughs—he did not come from Salem, did he?"

Winnie, noticing Jim's emotion, turned back to the original theme and continued: "And I suppose Juda was on your mind?"

"Yes, she was, and still I know it is wrong to worry about her, but I shall never cease to love that little angel. You know, I have lots of love letters she wrote me? She used to bring them over into the lot herself and then turn her back while I read them. She said she could not bear to see a man read a love letter. She was like her mother, artful as she could be. She used to enjoy our love spats, as she called them; she would pretend to get mad and go pouting around all day and expect me to come and make up with her, and sometimes it required lots of coaxing, but, of course, she always gave in at last. You see, now she is gone, I cannot help thinking about those things, and that is not all the trouble with me, either."

"That is enough, Jim. You need not tell your other[25] troubles. Come along to the grove, I want to talk with you."

Following the cart path they entered the woods, when she turned quickly and said: "Jim, I have something on my mind which I wish to unload, and you will not think me silly even if I am wrong?"

"No, no," he replied with a searching look. "I like to have you confide in me."

"Do you know, Jim, that I think there is a possible chance yet to find Juda alive."

He sprang to his feet as he exclaimed, "Tell me, Winnie, tell me all you know!"

"Do not get excited; I have no proof. Tell, me, Jim, all about the first day you were out hunting for Juda, who you saw and what they said?"

After he had gone through with the particulars she asked: "How many Indians camped at Wabbaquassett Lake that first night?"

"Only four, besides those regular lake dwellers."

"Did you see them all at one time?"

"Yes, we saw the four and talked with them. They came from the West."

"Were they Mohawks?"

"No, they were Narragansetts."

"Well, if Juda had been with the camp when you and Frank came upon them, could they have concealed her?"

"Certainly, but I do not think she was there."

"I do not think, Jim, she was killed by the wolves," said Winnie, as she frowned thoughtfully while looking on the ground. "If she is dead the Indians killed her."

"Did not you and all the neighbors, after we had gone, find the place where the wolves had killed her?"

"Oh, yes, Jim, I was there, but those Indians are so cunning. You see they broke camp about noon and that must have been about the time she would have arrived there. Now, if she arrived at the camp after they had gone, she could have come back home, but if lost, why did she not hear the calls for her, for the wolves disturb no one until after dark."

"Suppose your theory is true, Winnie, what steps would you take to find her?"

"Will you do what I want you to do about it?"

"Yes, Winnie, I feel like Queen Esther, when risking her life for her people."

"Queen Esther? Jim Hall, who taught you the Bible?"

He studied a moment and then said: "Go on about Juda, please."

Winnie scrutinized him keenly, then turned from the painful subject and continued about Juda. "I want you to wait several months until the Indians think we have given her up, then go quietly among the tribes; you know you talk all their tongues, and if you find her, Jim, I will love you for your bravery, and if you do not, the endeavor ought to count some. Now I suppose you want to go in and visit with papa and mamma."

"Y-e-s."

"What makes you drag out that 'yes' so long?"

"I thought you might like to take a walk in the grove."

"If you had not been so cross to me this morning."

"Well—but, I really did think—"

"What has changed your mind, Mr. Hall?"

"Well, Winnie."

"Well, Jim, say, do you really want to make up? Oh, catch me, Jim, my heart—my heart!"

Jim sprang and saved her from falling into the brook, as she pushed him from her and began laughing.

"Oh, Winnie, you do not know how you did frighten me, you are a roguish girl, but I like you and think you a perfect pet."

"Perfect pet—get out. Did you know John Bragg was over to see me?"

"John Bragg?"

"Yes, John Bragg."

"I thought you had given him up?"

"Oh, no. I did think when you and I came home from church on the black colt, it would give him a shock, but he is all the more attentive. Think of it, all the fathers and mothers have had their daughters cooing around him for the last three years and he does not bite, but is in great agony over me. Now, what can I do? I will have to marry him to get rid of him, won't I?"

"To get rid of him?"

"Oh, Jim, but his father is rich. You see, it is dignified to have such a beau. He came over last night after I left you and said his father had bought of Mr. Converse a beautiful saddle horse and he wanted me to take a ride on it, but when I told him I was engaged he looked downcast. He proposed to bring over his sister Lydia and, if it pleased you, we would all go up to the west bend fishing together and have a fish fry. What do you thing of that?"

"I would be delighted to go."

"Yes, but he will expect to escort me and leave you to attend to Lydia."

"That is all right; I like Lydia."

"You do?"

"Of course, I do."

"But, Jim, you are older than Lydia."

"I do not think she cares for that by what she said."

"What she said? When was all this talk?"

"Oh, not long ago."

"Not long ago? Look around here, James Hall!" At this he smiled and she said, "There, now, you were fooling me—own up that it was not true."

"It may not be exactly true, but bordering on the truth."

"What do you mean by bordering on the truth?"

"I actually saw her."

"Did you talk that way to her?"

"Oh, no; we did not speak."

"There, Jim, now I like you just a little bit; sort of sisterly love, you know. That is all, Jim—do you hear?"

"No," he said, drawing her to him. "I did not catch that last sentence. Come a little nearer, Winnie."

"Never! Never! James Hall," she said, withdrawing with a flushed face. "You are holding a secret from me and unless you confide all, Winnie Richardson will die an old maid."

"Thank God," he replied, with irony, "That cuts off John Bragg."

"John is already cut off. I love the tracks you make in the dust more than I do him, but no girl should allow herself to follow a love trail into a snare. You may be all right. I think you are, but do not advance another shade until I know all."

Jim dried her falling tears as caressingly as he dared, but the mystery still remained.

Winnie turned and gazed to the far away hills, but she did not see them, for her soul was silently summoning courage for the trying ordeal. Jim could but see in her[29] the model of pure virtue and loveliness, as she turned to him, saying:

"Is your name James Hall?"

"No."

"Were you ever married?"

"Yes."

"Is your wife alive?"

"No."

"What is your name?"

"James Burroughs."

"Is your father alive?"

"No."

"What was his name?"

"George Burroughs."

"Where did he die?"

"Salem."

"When?"

"August 19, 1692."

"Was he that George Burroughs?" Here Winnie's voice failed, and Jim answered, "He was."

Winnie stepped back while her thin lips parted and seemed to look as white as the ivories between them.

"Was your wife that beautiful Fanny Shepherd, who died with a broken heart at Casco Bay, after the report of your death?"

"She was."

Winnie stood a moment as if to satisfy herself that the world was real and she was not dreaming, then coming softly forward she sat on his knee and putting her arm around his neck began kissing him, while she said: "Mother is to have hot biscuits, butter and honey for supper, and we must go now, and after that I will give her a hint of what has happened, and we will take to the[30] parlor and you must tell me the story of your life, and you may talk just as serious as you please. Now, Jim, I want you to hug and kiss me for keeps."

Father and mother were puzzled to conjecture what had caused the turn in the tide, for the distance between Winnie and Jim had suddenly disappeared, and Winnie began bossing him around, just like regular married folks.

"Jim," said Winnie, as they entered the parlor. "Your clothes do not fit, your boots are too big, and your hair is too long. Oh, dear me, after we are married what a time I will have fixing you up. What makes you smile?"

"Who has said anything about marrying, Winnie?"

"I did."

"When is all this to take place?"

"Oh, it will be several months yet. You know, papa and mamma will want me to look nice and I will have to make all my new clothes. Now begin your story."

"Will you promise not to cry, Winnie?"

"Really, I will try. But think of it, it seems to me something like one rising from the dead; and still, believe me, dear, something of this kind impressed me from the day you arrived in Stafford, nearly eight years ago. If I should tell you my dreams you would call me visionary, but I will tell that some other time. Now begin and I will be good except when I want to pet you."

JIM'S STORY

I was born in Boston, May 1, 1670. My father, George Burroughs, then an ordained minister, was traveling on a circuit, preaching in stores, schoolhouses or any place where it was convenient, as most preachers did at that time. When I was four years old we moved to Salem, where father had charge of the Salem Mission, and when I was twelve years of age my mother died.

Father's liberal views did not please Samuel Harris and several other officials of the church, and they petitioned the presiding elder that he be removed.

Soon father learned that a settlement at Casco Bay, Maine, a landing on the coast nearly 100 miles north of Salem, had no preacher, so accordingly, one morning after a friend had given us our lodging, breakfast and two dollars in money, we started on foot for Casco Bay. The evening before leaving, we had spent several hours fixing up mother's grave, and as we passed by the yard the next morning we went in and knelt, and I remember how father thanked God that our angel mother had passed to the land of dreams, "Where the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest."

On our way along the north shore road, father preached several times, for which the people lodged, fed and gave us some money. On arriving at our destination, father announced that he would preach next morning, Sunday, in Gordon Richardson's barn. Well do I remember[32] the text, "Come unto me, all ye that are weary and heavy laden, and I will give ye rest." I noticed all paid close attention and some shed tears, and when we sang, all joined in and it seems to me I have never heard such voices since. It was a bright, clear summer day, all the little settlement was quiet, and when those standing outside joined in the chorus the peaceful strains seemed to waft my soul far away and make me think that I was with my mother.

After it was over Lucius Aborn, when shaking hands, said, "Your talk suits me, Mr. Burroughs, and although I'm not a church-going man, here is my dollar, and I want you and the boy to come right up to my house and stay six or eight weeks, and we will all pitch in and find you a place to live and preach."

CASCO BAY

Oh, how well we prospered in that little one-horse town, where there was little money, but the fields, orchards and gardens brought forth their fruit abundantly, while fish and game were plenty. The business center consisted of one large grocery and notion store, a sawmill, gristmill, fish and game market, and several large storehouses. I soon found employment in the store which was kept by Obadiah Stubbs, where I worked while I was not in school as long as I lived there.

At the end of one year, father had ninety members in his flock, and was still preaching in the schoolhouse. Eight years after our arrival, the congregation had built a commodious log and plastered church and father was receiving four hundred dollars salary, while I had saved two hundred dollars. With this and father's savings, we bought the Dimmick place, a comfortable village home.

On my twenty-first birthday I married Fanny Shepherd, a beautiful blue-eyed girl of eighteen, when we, with father, moved into our new quarters, and as Mr. Stubbs had proposed taking me in as a partner, we looked forward to a happy and prosperous life.

Father's affectionate acts and words to Fanny caused her to love him and, when we were blessed with a little baby boy, our happiness was complete, but, oh, how little did I dream of the dark storm that was gathering on yonder horizon, whose distant thunder I could not hear, and angry lightning I could not see, but whose dark mantle, when spread over, would cause me to bow down in grief, such as few ever realize.

DEACON HOBBS

Deacon Hobbs, returning in March, from Salem, stated in open church that he had learned that George Burroughs was not a regularly ordained minister, even if he once had been, and if he received spiritual aid, as he claimed, it was not the spirit of God, but that of the devil. He advised all members to beware of wolves in sheep clothing.

Father replied: "'An evil tree cannot bring forth good fruit.' Look to the right and left, Deacon Hobbs, and view the two hundred members working in the Master's vineyard. Compare my life of the past few years with yours. I, with my son's assistance, and the liberality of my flock, have saved enough to buy a modest home, while you have sponged up nearly half the wealth of this town. Your barns, storehouses, and pockets are full. I have not charged usury for money, cheated the red man out of his honest dues or trampled upon the rights of widows and orphans; all these things you have done. I[34] think I divine your purpose; but now listen, you steeple of soulless piety, neither insinuations nor acts will intimidate me. Not for an extension of this momentary life would I budge one hair to the right or left from the path my Master has laid out for me. He knows it all, and why should I fear?" At this point Hobbs left the church.

THE ARREST

On May 4, 1692, father, Fanny and myself were at the table with the baby boy in father's arms, he saying that it did not seem to him that the whole family was there unless he had the baby on his knee. As dear Fanny was joking him about feeding a baby two weeks old, two officers stepped into the room and read a warrant to him. It was for the arrest of George Burroughs as being suspected of being in complicity with the Devil. The warrant was dated Boston, April 30th, 1692. (See Boston Records.)

Without permission to bid us privately good-bye, his hands were shackled, he was placed on a horse, and they rode away at full gallop.

Fanny was in no condition to be left alone, but she urged me to saddle her father's horse at once and follow on. Soon the horse was waiting for me, but she could not let me go, she wept so bitterly while she flung her lovely arms around my neck, but at last with one sweet kiss she bade me hasten and said she would go home to Father Shepherd's until I returned.

Fanny, oh, Fanny! How little did I think the heart which loved me so fondly would soon be silent in the grave and I a fugitive and a wanderer—no friends, no home, and no one to love me.

Twenty miles away I caught up with them, when we rode nearly three days, with father's hands unnecessarily shackled, most of the time. The second day he said:[36] "Jimmy, this is my last earthly ride. The church is in error and will continue its injustice until some tragedy awakens the people, then it will be restrained. I may as well suffer as another. Jesus intends righteousness to eventually govern His church, but his professed followers are often blind to truth and righteousness, and will be until some great wrong is committed whereby they can place right against wrong for compromise. Do not weep, my boy, soon, in a moment as it were, you and I will stand before the judge, and who will this judge be? Our lives, just the plain record of our lives. There and then we can easily forgive those who have wronged us, but if we have wronged others, will their forgiveness to us set us free? Not unless a higher power steps in. Oh, this will be all right, my son, when the sunlight of Jesus shall awaken us to the new born day. I was thinking last night how glad I was that Jesus had already pleaded my cause. Oh, yes, the cause of poor unworthy me. Pray, pray, humbly my brave boy. Pray that you enter not into temptation and seek revenge. Do not forget that your Heavenly Father knows your inmost secret thoughts, and when you pray ask Jesus to forgive my tormentors, for as he said on Calvary, 'They know not what they do.'"

I will omit the bitter experience I passed through during father's sham trial and cruel execution.

THE MARTYRS

The public records of the execution of the Salem martyrs were:

June 10, 1692.

Bridget Bishop.

July 19, 1692.

Sarah Good, Sarah Wildes, Lizzie Howe, Rebecca Nurse, Susanna Martin.

August 19, 1692.

George Burroughs, John Proctor, George Jacobs, John Willard, Martha Carrier.

September 19, 1692.

Giles Corey.

September 22, 1692.

Martha Corey, Mary Easty, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Margaret Scott, Wilmot Reed, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker.

Abel Pike, John Richardson, Mary Parsons, Annie Hibbins, Margaret Jones, and others were known to have been executed, but there is no record of their arrest or trial at Salem. On the gallows, Richardson said: "Go on with your hanging, I do not want to live in a world with such fools."

THE ESCAPE

The evening after father's execution I started for Casco Bay, and on arriving at a tavern about ten miles out, I found two officers awaiting me. I was at once taken back to the same prison and placed in a cell to await my turn on gallows hill.

The jailer, whom I had know when a boy, said his orders were to give me bread and water once a day. He was a man about my size, but I knew that I was stronger than he; besides in a struggle for life, I believed my guardian angel would increase my power. I concluded that if once outside the jail, with ten minutes the start, I could reach the woods and make my way to some far-away Indian tribe and in time come and take Fanny and the baby to live with me among the natives, who, now, to me, seemed angels.

Accordingly, when he came about noon the third day, I pointed to the wall back of him, saying, "What is that?" and when he turned, I slipped my hand under his arm and seized him by the throat, and with the other in his long hair I broke him backwards over my knee to the ground, continuing my deadly grip until he ceased to struggle and lay like one dead. Then, quickly, before he revived, I slipped on his official garb and drawing his hat over my face started for the door, which I passed through and slammed behind me. Then lazily locking it and dangling the bunch of keys I had taken from him I walked towards Cotton Mather, who was standing, his[39] back to me, and unlocked one of the cells. Then, as he did not notice me, I passed him, and on turning towards the outer door I saw the jailer's assistant, who was talking to a female prisoner, whom I also passed without interruption. Stepping into the free world, I locked the door behind me, leaving the keys in the door, and walked down the road, to a woodshed, where I threw off the official garb and ran to the woods for dear life.

I now worked my way to Casco Bay with great difficulty. I could not travel nights, for fear of the wolves, so I crept cautiously along in the daytime through the woods and came down and slept in barns nights, where I usually found milk or eggs; and on the fifth day, as the sun was setting, I arrived in an opening on what we called Chestnut Hill, and looked down on the village of Casco Bay.

STUBBS' STORE

Oh, I wanted to see Fanny so badly, but I knew I was on dangerous ground, as officers would surely be waiting for me, and probably at Father Shepherd's was where they would expect to find me. Accordingly I decided to wait until midnight and then go down to Mr. Stubbs' store, where I had worked so many years, and could easily gain entrance, and hide among the boxes and lie there through the day to learn from overhearing what was going on about the village. So after breaking into the store and eating my fill of Stubbs' crackers and cheese, I fixed my nest under the dirty old front counter and fell asleep.

In the morning I heard the boy unlock the store, which reminded me of the times I first came there. He walked directly on the brown sugar hogshead and stood and ate for about three minutes, and then began to hunt for the broom while with his mouth full of cheese he tried to whistle a lively tune.

Soon another boy came in and I heard him say, "Hello, Ralph, did you hear about the 'tectives?"

"'Tectives—what is a 'tective?"

"Why, don't you know, Ralph? I have always known that. Besides father told us all about it this morning. They are officers with their coats buttoned up, and you would think they were real men until they catch you and take you to jail and hang you; so father says."

"Gracious alive! Have you seen a live one, Bill?"

"No, I never have, but father has. He said there were two hanging around Uncle William's last night. He thinks they are the same ones which carried off our minister, and he says he don't know who they are after unless it is Jim Burroughs, and it can't be him, either, for he is dead, they say the Indians or wolves have eat him up."

"Golly, that's strange, Bill. Maybe they're after Jim's wife. You know them pleggy ministers at Salem kill lots of good folks."

"Oh, no, Ralph, no 'tectives haven't touched her, because she's got a baby, besides she is awful sick. When she heard Jim was dead she went right into spazumbs or something, and she is going to die. Why, she moans so loud we can hear her clear over to our house. Mother said she was crazy all day and thought that Jim was at the foot of the bed and would not take her in his arms. She kept saying, 'Oh, Jim, Jim, don't you love me any more, won't you let me put my arms around your neck and kiss you once more before I die?'"

Here the conversation ended, and I could see Ralph with his arm on Bill's shoulder both sobbing and wiping the tears with their dirty sleeve and I bowed my face down and moaned until Ralph said, "What was that noise?"

Stubbs came in and said, "Ralph, why have you not swept the floor?"

"Because I can't find the broom. Besides Bill has been telling me all about how sick Jim Burroughs' wife is, and how there is 'tectives around here to catch some one—I think you had better look out."

"It isn't 'tectives, Ralph, say detectives. Do wipe the sugar off your mouth and speak more proper."

"Didn't know there was sugar on my mouth—Oh, yes, there was a lump fell out of the hogshead when I was sweeping, and it was so dirty that I did not like to put it back into the clean sugar, so I ate it."

"I thought you said you had not swept, for you could not find the broom."

"Oh—I—yes—say, Mr. Stubbs, did you ever see a live detective?"

"Now, that will do, Ralph; never mind the sweeping; go and count Mrs. Armstrong's eggs, for she is waiting. Now, Ralph, do not count double-yelk eggs for two any more, do you understand?"

"I don't see why, as long as there might be a rooster and a pullet."

"Yes—yes—Mrs. Armstrong, he is coming as soon as he grasps the cause of twins."

PAUL DIMOCK

Stubbs and the boy now trudged around the store waiting on customers until about 10 o'clock, when Paul Dimock came in and engaged Stubbs in an undertone, but being directly over my head, I could hear all. "I have learned," said Dimock, "that two detectives are stopping at Deacon Hobbs', and have been several days, and no one knows who they are looking for."

"You see, Paul," said Stubbs, "that Hobbs was instrumental in Brother Burroughs' arrest, and I have been told his daughter, Abigail, swore at Salem that she saw two black devils standing behind Brother Burroughs while praying—"

At this point a third party came in, and I recognized the well-known voice of Susan Beaver.

"Isn't it awful about Deacon Hobbs?" she said. "I suppose that is your secret? Why, I do think it is just terrible."

"What news, Mrs. Beaver? What have you heard?"

"Why, last night when Tom came home late, he said he saw two strangers come out of the woods and sneak into the deacon's house. So, out of curiosity, Sarah and I slid around and peeped in at the window, and sure enough there they were, eating supper and the deacon was—hush, there comes old Hobbs now."

"Good afternoon, Deacon," said Stubbs, "what is the news?"

"Bad news, awful bad. They say Fanny Burroughs is very low. My heart aches for that family. James was a good boy, and I wonder if anyone knows for certain that he is dead. I think possibly he may be among the Indians yet, although Shepherds' folks are sure he is dead, or he would come to Fanny. I suppose you have no particulars. Then there was George, his father, that they hung down at Salem. I wonder where they got evidence to convict him? To be sure, he and I did not exactly agree as to our religious views, but I never took that to heart, and would have done all I could to have saved him, even if he was not a regular ordained minister. I think from his record here that he was honest, don't you, Mr. Dimock?"

"Yes, Deacon Hobbs, I do. And James, his son, was an honest, upright and worthy citizen, and whoever was instrumental in causing those officers at Salem to come into our midst and take them away and murder them outright will surely repent when it is too late. I believe[44] they have imprisoned Jim, and either have or will hang him, for the report of his being killed by the Indians, or wolves, may have come direct from Salem. Oh, Mr. Hobbs, it shatters my faith, that our Heavenly Father allows such men to live. This is terrible," he uttered, as he wiped the perspiration from his face and repeated, "terrible, terrible." Then as if aroused by wrong, he raised his voice as he faced the deacon, and continued: "Deacon Hobbs, I am no more safe than they were. If an officer should come in here now and arrest me for complicity with the devil, I should consider it my death knell, would you not?"

"Well, really," began the deacon, "I do not know. You see, I have been down to Salem and talked with Cotton Mather and others prominent in the church, and they seem to be worthy Christians. I have thought George Burroughs may have been convicted of some other crime. You see, the prison is closely guarded and all we get is hearsay."

SUSAN BEAVER

The reader will remember that Susan Beaver was talking when the deacon came in, and now stood listening to his subterfuge, and Dimock's stinging insinuations. As I remember Susan, she was short, stout, with black eyes, glistening teeth, and quick movements. She tried to keep silent, but now her cup of wrath was full, and reached the high-water mark, where danger could not restrain the break, and she broke:

"Deacon Hobbs, you miserable old liar, I saw the detectives in your house myself. Maybe they're waiting to take my husband to Salem. If so, you can inform them that they can never cross our threshold unless it is over my dead body. You say you do not know much about it. Was not Abigail at Salem, swearing against the minister? Did not you both swear he was in league with the Devil? Now you say he may have been convicted of some other crime. George Burroughs, that worthy Christian minister, defile his name, now he is dead, will you? Oh, you ought not to live another minute," and suiting the action to the word, she sprang across the store to the old cheese box. Now, I knew the cheese knife was long and heavy, and in the hands of a desperate woman. Bang-slam-bang, they went around and around the store, he holding a chair before him and crying, "Help! Murder!" while she struck out wildly without speaking a word. Dimock and Stubbs sprang[46] in to save the deacon's life, but when I peeped through the crack and saw the broad grin on Dimock's face, I concluded their interference was not genuine. The deacon worked around the counter, when she sprang on top and had him in a trap, at which he dropped his chair and ran and plunged through the window headlong. After he had escaped, and Susan had time to think, she sat down and began to cry, but on being assured by Dimock that no one would think the less of her, she left the store.

While Paul was helping board up the broken window, I overheard Stubbs ask him: "Do you consider Cotton Mather and his associates murderers?"

"Oh, no," was the reply, "not exactly that. It is a phenomenal wave of insanity. Similar waves have spread their gloomy pall over the innocent, long before Joshua put the women and children to death at Jericho. These Salemites are at war with the Devil on the same principle that one nation wars with another; they justify themselves through a spasmodic lunacy, that duty calls them to kill their fellow beings.

"God works in a mysterious way. Cotton Mather may be blind. He may be a tool in the hand of a higher power. Finite beings do not comprehend the infinite. If God permits, does He not sanction? These cruelties will have a tendency to humanize Christianity. When years have passed and Brother Burroughs thinks over earthly life he will not regret that his Maker called him home at noon. Friendship and love will increase towards the Burroughs family. They are just leaving their lights along the shore. The love of Jesus will spread when the church shall have hatched out of its shell of ignorance; then it will stand on a higher and more liberal plane;[47] midnight to us may be morning to the angels. Do you know, Stubbs, what is the main trouble with the human family?"

"I do not, Paul. What is it?"

"It is that they know less than they are aware of."

After the store had been closed and Stubbs was working on his books, I heard the door open and some one come in.

"Good evening, doctor. How is Fanny Burroughs?"

The doctor came near and replied in an almost inaudible voice, "She is dead." The little bullet-headed doctor was affected, for I could hear his voice tremble. "Oh, well," he replied to Stubbs' inquiry, "She had no disease, the poor girl actually died of a broken heart. Such suffering I never saw before, but when she did go if you had seen her, Stubbs, you would never question the theory of life beyond dissolution of the body. She raised her eyes upwards, smiled so sweetly and said: 'Oh, father, father, where is Jim?' I am sorry, Stubbs, I have not led a better life, for I have known Fanny Shepherd since she was born and if God will forgive the past, I will turn over a new leaf and try to meet her when I die. I know now that our minister, whom I always ridiculed, was right there in the room with us when she was dying. Besides, Mr. Stubbs, I believe Jim is alive, for if he had been dead he would have been the first one for her to recognize. You see, she was expecting to see him and he was not there."

Here Jim's heart and voice seemed to fail and Winnie put her arm around his neck and they sobbed convulsively for a moment and then continued.

When all was still I crept from my hiding place, washed my face, but could not eat. As usual, the shutters[48] were closed, so I lit a candle and began to rummage around the store. I found Stubbs had a new musket with a horn of powder and a bag of shot, and as I knew he would gladly give them to me, I took them. Then I waited until near dawn, when I went out to the hill in the woods and stayed all day, on the very spot where I had spent many happy hours with Fanny. I could look down into the room where I had courted and wedded my dear Fanny, and could see part on one of her arms, as her body lay near the window, in Father Shepherd's house. Also I saw the village carpenter making my Fanny's coffin and a stranger digging her grave. That night I slept in the store again and the next day, from the same hill, I saw them lower her body into the grave, but my heart was locked in despair; I could not weep.

REVENGE

At night I came down and went to the grave. The distant stars seemed to be shedding their soft light on a lonely world, while the moon about setting cast her ghastly beams among the chestnut trees, making the scene, oh, so lonely, in that silent little graveyard. Out upon the cold waters of the bay I could see the silver waves glisten in the moonlight among the familiar bayous, which I should never see again, while far beyond the bosom of the great Atlantic seemed to heave a sigh of grief at my loneliness. I fell upon dear Fanny's grave, kissed the clay and wondered if she was there. Then breathing a long farewell, I folded my hands in prayer, asking God to forgive me for the crime I was about to commit.

Hastily I then walked towards Stubbs' store, resolved to settle with Deacon Hobbs and then turn my back on white man forever. I entered the store and wrote on a slip of brown paper: "Obadiah Stubbs, a friend has taken your gun and ammunition," and placed the slip in the cash drawer.

When outside of the store I walked lively to the deacon's nearest storehouse, then ran from one to the other, and at last set fire to his home, then stepped back into the lilac bushes and cocked my gun.

Soon I saw great curls of smoke ascending from the storehouses on the wharf, then the barns and sheds, and now the home had caught fire. Then seeing the family[50] in danger, to awaken them I seized a rock and dashed it through the window.

The family were now aroused and Hobbs ran to the well for water, when I raised my gun, but a shadow came before me, and I could not see him. Again he ran out and again I raised the gun, determined to kill him, just as I felt a soft pressure on my shoulder and turning quickly I found myself alone. Then I knew I must not.

As I walked away from old Chestnut Hill, I gave one last, lingering look. It was now daybreak, and as I gazed down on the little village where I had spent so many happy days I saw that all of Deacon Hobbs' wealth had ascended into smoke. Stubbs' old store looked as dingy and dirty as ever. Father's church, on which I had often looked so fondly, now seemed silently waiting to catch the first glimmer of the morning sun as it came to give light and life to the hills and valleys of old New England. Father Shepherd's house, the door through which I had passed so many times with a light heart, were all plain to my view. Once more I looked through the trees to the grave of Fanny and walked away.

ALONE IN THE WILDERNESS

About noon, the first day out, I met three Indians and we took lunch together, they furnishing bear meat and I cheese and crackers, which I had borrowed from Stubbs. After this I trudged on, following an old trail in a westerly direction, hoping to find Indians who could give me shelter for the night, but finding none, I started a fire at dark to scare the wolves away and prepared to stay in the woods alone.

As darkness came on and my fire lit up the woods, I was lonely and yearned for a friend, while a strangeness came over me which caused me to shudder. The excitement had past, and I was left to contemplate as to the course I had taken and where my pathway of life might be leading me. I saw myself, as only a short time before, a promising young man of the wild wood harbor village; but now alone in the wilderness, soon to be a ragged, friendless outcast. Was my condition better or worse than Fanny's or father's? Silently I knelt and implored the unseen to forgive all and keep me pure in heart as I wended my way over mountains of trouble and through vales of temptation.

While pondering I heard the flapping of wings, and a large owl came and lit on a dry limb above me and began its lonely hooting. The night was still, save the occasional bark of a wolf and the echo of the bird's dreary chant, which under ordinary circumstances would have startled[52] me, but now rising to my feet I gazed at the intruder with an eye of gladness and longed to caress him as a friend, while I murmured, "Your lot on earth as compared with mine is to be envied. Carelessly and thoughtlessly your days pass with no regret for the past or anxiety for the morrow, while my sympathetic heart, actuated by an ingenious brain, dashes cold waves of sorrow against bleak rocks of cruel destiny."

I closed my eyes and again implored my Heavenly Father to increase my strength to tread the thorny way. Then I pondered over my condition again and cried, "Oh, the heart—the human heart—that beats in sympathy! Oh, the soul that longs to comfort some one and yearns to be loved in return!"

Gazing high into the far away Eternity where all seemed lovely and serene, I said, "Silence is the token of love. Fanny is; yes, she still lives, but she is silent and in her silence she loves me still."

Then the stars, hills and trees, like friends, came near and shared with me my troubles, and as I sank upon the ground overcome I thought I was a child again and mother whispered low and sweet, "Love your enemies and Jesus will love you."

Resting upon a bed of leaves with my boots for a pillow, the angel of dreams took me in her fair arms. Fanny and I were walking beside a laughing crystal stream, gathering wild flowers, whose fragrance seemed to fill the balmy air, where familiar birds came and warbled sweet notes over our heads while the soft sunshine bore upon the scene, peeping into the shady grove and forming our peaceful nook into a perfect bower of love. Here upon a bank strewn with tiny violets I kneeled at Fanny's feet and asked her to become my wife. She did not speak, but looked on me with her own sweet smile as she glided softly away. I arose to follow her, when I awoke and found myself alone in the dark woods.

POOR JIM, LONELY BUT NOT ALONE, FANNIE IS NEAR.

Morning came at last, and not being able to taste my food, I trudged on, and in a few days reached Springfield, where I first assumed the name of James Hall. There I worked about ten days for a man named Anson Newell, but when I learned there were two families there from Salem I feared detection and decided to go.

HUNTING FOR BABY

I now abandoned the idea of living with the Indians and worked my way over the Green Mountains, then down the Hudson River to New York. During the winter my mind was continually on my baby boy, and when spring came I started East to try to locate him. At Hartford I stayed a few days, hoping to find someone from Casco Bay, but being unsuccessful I went on and spent the night with about thirty Indians in the dark grove south of Wabbaquassett Lake. Here I found a buck and his squaw, who had lived near Casco Bay, but they knew nothing of church affairs.

Next morning near Stafford, just as I was turning north from the river bend, I met a party of hunters, one of whom I recognized as Josiah Converse, from near Casco Bay. After passing, I overheard him remark—"That man looks and walks just exactly like Jim Burroughs, and if I did not know he was dead, I would swear it was he." This remark disturbed me, for I had thought that my full beard and shabby clothes had disguised me. Soon I passed near my baby boy but did not know it.

When I arrived at Casco Bay I was puzzled as to how I was to get my information. Stubbs' store could not be approached now, as I had left traces of my last visit and someone might be on the alert, so I hung around Chestnut Hill three days, secreted near the road, hoping[55] to see someone passing who was a stranger. Several acquaintances passed each day, among whom was old Deacon Hobbs, which made my blood boil, and I almost forgot that I was to love my enemies. One day a strange boy approached and I ran up to the brow of the hill and then turned and met him.

"Does Deacon Hobbs live in this town?" I inquired.

"Yes, he lives over there in that cottage."

"Do you think he wants to hire a man?"

"Oh, no, he does not want help. He is poor now; all he had is burned up."

"Who did it?

"We do not know, but think it was an angel from heaven, and every one is glad."

"Why were they glad?"

"Oh, because he killed the minister. That was last year, and I was not here."

"How did he do it?"

"Well, he did not kill him, but he got some folks down in Salem to come up and arrest him and they hanged him."

"Did he kill anyone else?"

"Yes, he killed James Burroughs and Fanny, too, so Mr. Shepherd says."

"Who were they?"

"James was the minister's son and Fanny was his wife. I live with the Shepherds and heard them say these things."

"Did James and Fanny have any children?"

"Yes, they must have had one, for I heard Mrs. Shepherd tell how the minister's sister came on from Boston and took it home with her."

Then looking inquiringly in my face, he said, "Say, mister, are you sick?"

"Oh, no," I replied, and we passed on.

On arriving at Boston I learned that uncle had died and Aunt Hannah had gone with her sister, Abigail, who lived in Salem. In Salem, with great difficulty, I learned they had sold out all their property and gone West. All further efforts were fruitless and I returned to New York and began to work at my last winter's job, where I worked quietly, ever on the alert to gain tidings of my boy.

MULDOON

One day while I was working with an Irishman named Muldoon, the proprietor, Mr. Benjamin, came along, leading his little daughter, who, pointing to Muldoon, said, "Papa, what makes you hire paddies? I do not like them." Muldoon resented the innocent prattle, and turning to Benjamin, said: "Will ye allow that wee bit of a brat to spake that way of a gintleman?"

"You are no gentleman to call a child a brat, and if you answer back I'll discharge you at once."

Pat tugged away in silence and when Benjamin had gone he said: "I niver knew but one mon in me life as mane as ould Benjamin and that was Cotton Mather himself."

"What do you know about Cotton Mather?" I eagerly inquired.

"Nothing good, sir."

"Were you ever at Salem?"

"Do yees think that auld Ben aught to larn that wee bit of a snipe to insolt the loikes of me?"

"But, Pat, that does not answer my question."

"Thin why should a gintlemin aloix yee be axen meself quistions which I niver knew a-tal-tal?"

"Yes, you do know, and if I explain why I am so anxious you'll tell me all you can, won't you, Pat?"

"Yees moight be an officer."

"Nonsense, Pat, haven't you worked beside me for a long time?"

"Sure, but you moight be."

"No, I am not, and you should not be afraid, for you have never committed any crime."

"Oh, but it was the innocent that they murthered. But, Jim, if yees will lit me come to your room at the did o' night and yees will kiss the Holy Cross and hold the sacred Mary to your heart while ye swear niver to till, I might till yees the bit I know."

When Pat arrived at midnight he whispered in my ear, "Ye see, that if Cotton Mather hears that I till the truth he will git some one to swear I am posist with the devil and they will hang me sure."

After I had explained to him how large a dowery had been left for the Burroughs family, and that a child had been lost, he said: "Then it is not Giles Corey yees are after hearing, for I might tell yees more about him, for I lived with him both before and after he was dead."

"No, I want you to tell me all about George Burroughs. Did you ever hear about him?"

"Faith and indade, I did, I heard him make his last prayer when on the gallows, asking God to forgive his inimies and we all wipped loike babbies, we did."

"Did he have a family?"

"Yis, a son. A fair young mon. He looked so much loike yees that I think of him when yees walk along, but he is dead, poor bye. When he started home he lost his way and the wolves ate him. Some said he may not be ded, but shot up in prison to be hung, but I know he was dead, for I hilped to bury his bones."

"Did you see them?"

"No, they were in a box, but I knew he was ded, fer he did not smill like a live man, and his wife died, but they had a little one, who is alive now."

"Where is he?"

"He was first taken to Boston to his Aunt Hannah's and thin to his Aunt Abigail's in Salem, thin a man came on from Stafford, Conn., and took him to keep. His wife was Aunt Hannah's daughter and Aunt Agibail wint to Stafford hersilf."

The day I arrived at Stafford Street I walked from Hartford, and the nearer I came the faster I walked. When I arrived at the village some men were working on the road and in answer to my inquiry, said: "The widow Abigail Drake lives in that red house," which they pointed out. I called on her under the pretense of buying her home, and staid quite a while. She mentioned some of the best families, Deans, Converses, Richardsons, etc., but I could not find out who had the boy until I spoke of the church, when she mentioned that Deacon Felker had adopted a boy who was her nephew. Then I asked her who his parents were. She hesitated, and then said, "His father and mother are both dead."

"Were you acquainted with his father?"

"Yes, I was; he was a man about your build, only when I saw him last he was in trouble, and pale and thin."

"What trouble?"

"Trouble," she replied wiping the tears away with her apron. Then coming near me inquired quizzically, "What is your name?"

I saw she was on the point of detecting me, and looking straight in her eye I answered, "James Hall."

Again she hesitated and then said, "You do look so much like James Burroughs, who is dead, that I thought[60] the dead had been raised." She then told me all about father's execution, Fanny's death and mine, after which I walked over to Deacon Felker's.

When I arrived, there was no one in but the deacon, so I struck him up for a job. Soon I saw a lady coming up the walk who I at once recognized as Cousin Phoebe, whom I had not seen for fifteen years. Beside her ran a little boy. The deacon introduced me, and in shaking hands I squeezed hers so hard that she looked up quickly, then presuming me to be very rough, she spoke pleasantly. Then I picked up my own little boy and as in some phantom mirror, Fanny seemed to look me right in the face.

While waiting for tea, Winnie Richardson came in and adroitly introduced herself by saying, "I presume our town looks tame to you, especially if you've been living in the city, but to us who have never traveled Stafford is the center of the world."

At the conclusion of Jim's story the sweet Winnie softly caressed the troubled man with her arm around his neck, and here we leave Winnie and Jim, to whirl and swirl in their frail barques of life, on the restless waves of time, until they mysteriously cross the bar out into the unknown ocean of Eternity, from whence, if they return to guide our thoughts, we do not comprehend it.

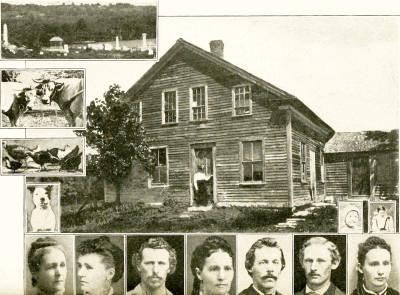

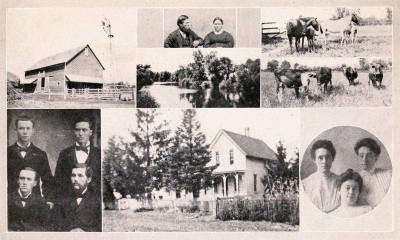

OUR MOUNTAIN HOME NEAR WABBAQUASSETT LAKE, BUILT BY WARREN

RICHARDSON, 1832.

PORTRAITS OF CHILDREN, 1870, EXCEPT MARIETTE. LEFT TO RIGHT. ELIZA,

ADELIA, COLLINS, CAROLINE, MERRICK, GORDON, JANETTE.

OUR WABBAQUASSETT MOUNTAIN HOME

John, my Grandfather Richardson, son of Uriah, built his home on the east side of the Devil's Hopyard, while Abner, one of John Dimock's ten sons, built his home on the west side.

John Richardson raised a family of boys, John, Warren, Collins, Marvin, Orson, and one girl, Fanny, while Abner Dimock raised a family of girls, Lovey, Manerva, Luna, Hannah, Arminia, Abigail, and one boy, Abner.

Warren Richardson crossed the Hopyard, wooed and won Luna Dimock, and they built their nest near Wabbaquassett Lake, where the flowers bloom in early spring, wild birds awake the summer morn and the babbling brook sings through the winding vale below, all day long.

Here they raised a group of laughing, frolicing, romping backwoods mischief and their names were:

Mariette A.—Married Frank Slater.

Eliza L.—Married Lucius Kibbes.

Adelia A.—Married Epaphro Dimock.

Caroline C.—Married Lucius Aborn.

Collins W.—Married Martha Aborn.

Merrick A.—Married Mary Hoyt.

Gordon M.—Married Amanda Pitt.

Janette A.—Married George Newell.

Wabbaquassett retained its virgin bloom of nature long after the surrounding country had been occupied by white invaders.

Stafford, Ellington, Somers and Tolland Streets had become self-centered, while the sleeping beauty, Wabbaquassett, was held by the Nipmunks as a sort of rendezvous for the Pequods, Mohegans. Mohawks, Narragansetts and several other tribes who were roaming over New England, stealing fowls, cattle and even children, for the red man felt that the brooks, lakes and forests, together with all they contained, virtually belonged to him.

Wabbaquassett of old, with its broad sandy shore, dreaming in the protecting arms of a dense forest of oak, pine, chestnut and maple giants was truly the gem of New England.

When the Richardsons, Dimocks, Newells and Aborns began their encroachment into these forests the Indians were loath to leave their pow-wow home in the oak grove, on the south shore of the lake, for the American Indian dreaded the law more than the tomahawk, but the following instance routed them.

A buck named Wappa, who lived on the shore, south of the old West Rock, killed his squaw, Dianah, for which he was tried at Tolland Street and hanged. On the gallows he saw Captain Abner Dimock, my mother's father, among the spectators and called for him to come on the gallows and pray for him.