145

["Eating sugarplums is the best cure for mundane sorrows."—A Ladies' Journal, Sept. 19.]

By some stordinary mistake on the part of some wery hemenent taker of Poortraits, I was last week requested for to go to him and set for my Picter.

He told me in his letter that his reason for wanting me to set to him was, becoz he wanted to have the Picters of all the Members of the Copperation, and of course they wood not be complete without mine, for tho of course he knew that I was not a real Common Counseller, still, he thort that I had left sitch a mark among them by my ten years constant service and unwarying atention to em, that the hole matter woud be wanting in completeness if my Picter was omitted, even if it was only as "Mr. Robert the City Waiter" a leading off the presession or a bringing up the Reer! I remembers werry well when the other City Picter was printed, about a year ago, when the Lord Mare's three Footmen, all in their werry hansumest uniforms, was placed exactly in the front, and all being fine hansum fellers, as they undowtedly is, they were thort to have taken the shine out of the hole Picter, but that was in course quite a diffrent thing, and this new one is to be quite werry diffrent from that one, and carried out in quite another style altogether, and will, I shoud think, atract such uniwersal admiration as will quite cut out the Picter Gallery as was shown at Gildall last summer.

Sum few of the werry hansumest of the hole Court as has bin and got taken already, has bin and stuck theirselves up in the Reading Room, and werry proud they is of their apperience, and Brown and Me has got sum of the Atendents to let us go in before the Members comes, and see em privately. Brown says as how as he's quite sure as there must be sum mistake about me, becoz as he carn't at all see how I shoud fit in with the rest. But there's werry little dout in my mind that it's all a case of gelosy with Brown, who woud werry much like to have sitch a chance.

I had my chance of going yesterday, and werry kind the Gennelman wos who took me, and he took me three times, to make sure of me. He said as I was a werry good Setter, and that everybody woud know who I was by my likenesses in Punch, and lots of peeple woud like to git my Picter, as it was a werry good likeness.

Or, Evolution Gone Wrong.

["It is probable that the butterfly postillion, by an inverse process of evolution, becomes in time the sombre fly-driver."—James Payn.]

(By a Light Sleeper.)

(An Elderly would-be Wheelman's Experience.)

146

MAKING THINGS SMOOTH.

Keeper (to Sportsmen, who have just fired all four barrels without touching a feather). "Deary me! uncommon strong on the Wing Birds is, Gentlemen! 'Stonishing amount o' Shot they carries away with 'em to be sure!"

[A late report of the Automatic Machine Company says that out of every twelve coins placed in the slot two are bad.]

Average "Honest Man" loq.:—

In the Press.—The Cruelty of the Jap. By the Author of The Kindness of the Celestial.

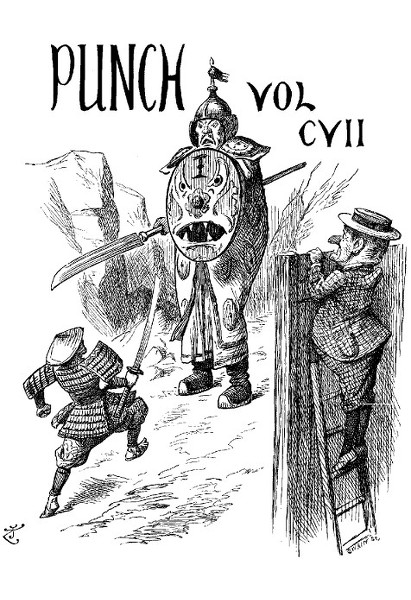

Scene—The "Gothenburg Arms," under new (Municipal) Management, licensed for the sale of liquors for the public profit only. Mr. G., an elderly but cheerful and chatty customer, and Miss Josephine, a smart barmaid, discovered conversing across the counter.

A LITTLE FLIRTATION.

Mr. G. "Yes, Miss, I entirely agree with you. 'Local Option' is—is—um—more or less of an Imposture."

Miss Harcourt (horrified, appearing in the doorway). "Oh! Mr. G.! Mr. G.!!"

["... Local option ... if pretending to the honour of a remedy, is little better than an imposture.... I am glad to see that Mr. Chamberlain is active in your cause."—Extract from a Letter written by Mr. Gladstone to the Bishop of Chester. See Daily Paper, Sept. 19.]

147

The Plea of the Party Scribe.—It is said that "upright writers" avoid scrivener's palsy or penman's cramp. Perhaps so. But then there is so little demand for upright writers! 148

(A Story in Scenes.)

PART XIII.—WHAT'S IN A NAME?

Scene XXII.—At the Supper-table in the Housekeeper's Room. Mrs. Pomfret and Tredwell are at the head and foot of the table respectively. Undershell is between Mrs. Pomfret and Miss Phillipson. The Steward's Room Boy waits.

Tredwell. I don't see Mr. Adams here this evening, Mrs. Pomfret. What's the reason of that?

Mrs. Pomfret. Why, he asked to be excused to-night, Mr. Tredwell. You see some of the visitors' coachmen are putting up their horses here, and he's helping Mr. Checkley entertain them. (To Undershell.) Mr. Adams is our Stud-Groom, and him and Mr. Checkley, the 'ed coachman, are very friendly just now. Adams is very clever with his horses, I believe, and I'm sure he'd have liked a talk with you; it's a pity he's engaged elsewhere this evening.

Undershell (mystified). I—I'm exceedingly sorry to have missed him, Ma'am. (To himself.) Is the Stud-Groom literary, I wonder?... Ah, no, I remember now; I allowed Miss Phillipson to conclude that my tastes were equestrian. Perhaps it's just as well the Stud-Groom isn't here!

Mrs. Pomfr. Well, he may drop in later on. I shouldn't be surprised if you and he had met before.

Und. (to himself). I should. (Aloud.) I hardly think it's probable.

Mrs. Pomfr. I've known stranger things than that happen. Why, only the other day, a gentleman came into this very room, as it might be yourself, and it struck me he was looking very hard at me, and by-and-by he says, "You don't recollect me, Ma'am, but I know you very well," says he. So I said to him, "You certainly have the advantage of me at present, Sir." "Well, Ma'am," he says, "many years ago I had the honour and privilege of being Steward's Room Boy in a house where you was Stillroom Maid; and I consider I owe the position I have since attained entirely to the good advice you used to give me, as I've never forgot it, Ma'am," says he. Then it flashed across me who it was—"Mr. Pocklington!!!" says I. Which it were. And him own man to the Duke of Dumbleshire! Which was what made it so very nice and 'andsome of him to remember me all that time.

Und. (perfunctorily). It must have been most gratifying, Ma'am. (To himself.) I hope this old lady hasn't any more anecdotes of this highly interesting nature. I mustn't neglect Miss Phillipson—especially as I haven't very long to stay here.

[He consults his watch stealthily.

Miss Phillipson (observing the action). I'm sorry you find it so slow here; it's not very polite of you to show it quite so openly though, I must say.

[She pouts.

Und. (to himself). I can't let this poor girl think me a brute! But I must be careful not to go too far. (To her, in an undertone which he tries to render unemotional.) Don't misunderstand me like that. If I looked at my watch, it was merely to count the minutes that are left. In one short half hour I must go—I must pass out of your life, and you must forget—oh, it will be easy for you—but for me, ah! you cannot think that I shall carry away a heart entirely unscathed. Believe me I shall always look back gratefully, regretfully, on——

Phill. (bending her head with a gratified little giggle). I declare you're beginning all that again. I never did see such a cure as you are.

Und. (to himself, displeased). I wish she could bring herself to take me a little more seriously. I can not consider it a compliment to be called a "cure"—whatever that is.

Steptoe (considering it time to interfere). Come, Mr. Undershell all this whispering reelly is not fair on the company! You mustn't hide your bushel under a napkin like this; don't reserve all your sparklers for Miss Phillipson there.

Und. (stiffly). I—ah—was not making any remark that could be described as a sparkler, Sir. I don't sparkle.

Phill. (demurely). He was being rather sentimental just then, Mr. Steptoe, as it happens. Not that he can't sparkle, when he likes. I'm sure if you'd heard how he went on in the fly!

Steptoe (with malice). Not having been privileged to be present, perhaps our friend here could recollect a few of the best and repeat them.

Miss Dolman. Do, Mr. Undershell, please. I do love a good laugh.

Und. (crimson). I—you really must excuse me. I said nothing worth repeating. I don't remember that I was particularly——

Stept. Pardon me. Afraid I was indiscreet. We must spare Miss Phillipson's blushes by all manner of means.

Phill. Oh, it was nothing of that sort, Mr. Steptoe! I've no objection to repeat what he said. He called me a little green something or other. No; he said that in the train, though. But he would have it that the old cab-horse was a magic steed, and the fly an enchanted chariot; and I don't know what all. (As nobody smiles.) It sounded awfully funny as he said it, with his face perfectly solemn like it is now, I assure you it did!

Stept. (patronisingly). I can readily believe it. We shall have you contributing to some of our yumerous periodicals, Mr. Undershell, Sir, before long. Such facetious talent is too good to be lost, it reelly is.

Und. (to himself, writhing). I gave her credit for more sense. To make me publicly ridiculous like this!

[He sulks.

Miss Stickler (to M. Ridevos, who suddenly rises). Mossoo, you're not going! Why, whatever's the matter?

M. Ridevos. Pairmeet zat I make my depart. I am cot at ze art.

[General outcry and sensation.

Mrs. Pomfr. (concerned). You never mean that, Mossoo? And a nice dish of quails just put on, too, that they haven't even touched upstairs!

M. Rid. It is for zat I do not remmain! Zey 'ave not toch him; my pyramide, result of a genius stupend, énorme! to zem he is nossing; zey retturn him to crash me! To-morrow I demmand zat Miladi accept my demission. Ici je souffre trop!

[He leaves the room precipitately.

Miss Stick. (offering to rise). It does seem to have upset him! Shall I go after him and see if I can't bring him round?

Mrs. Pomfr. (severely). Stay where you are, Harriet; he's better left to himself. If he wasn't so wropped up in his cookery, he'd know there's always a dish as goes the round untasted, without why or wherefore. I've no patience with the man!

Tred. (philosophically). That's the worst of 'aving to do with Frenchmen; they're so apt to beyave with a sutting childishness that—(checking himself)—I really ask your pardon, Mamsell, I quite forgot you was of his nationality; though it ain't to be wondered at, I'm sure, for you might pass for an Englishwoman almost anywhere!

Mlle. Chiffon. As you for Frenchman, hein?

Tred. No, 'ang it all, Mamsell, I 'ope there's no danger o' that! (To Miss Phillipson.) Delighted to see the Countess keeps as fit as ever, Miss Phillipson! Wonderful woman for her time o' life! Law, she did give the Bishop beans at dinner, and no mistake!

Phill. Her ladyship is pretty generous with them to most people, Mr. Tredwell. I'm sure I'd have left her long ago, if it wasn't for Lady Maisie—who is a lady, if you like!

Tred. She don't favour her ma, I will say that for her. By the way, who is the party they brought down with them? a youngish looking chap—seemed a bit out of his helement, when he first come in, though he's soon got over that, judging by the way him and your Lady Rhoda, Miss Dolman, was 'obnobbing together at table!

Phill. Nobody came down with my ladies; they must have met him in the bus, I expect. What is his name?

Tred. Why, he give it to me, I know, when I enounced him; but it's gone clean out of my head again. He's got the Verney Chamber, I know that much; but what was his name again? I shall forget my own next.

Und. (involuntarily). In the Verney Chamber? Then the name must be Spurrell! 149

Phill. (starting). Spurrell! Why, I used to—— But of course it can't be him!

Tred. Spurrell was the name, though. (With a resentful glare at Undershell.) I don't know how you came to be aware of it, Sir!

Und. Why, the fact is, I happened to find out that—(here he receives an admonitory drive in the back from the Boy)—that his name was Spurrell. (To himself.) I wish this infernal Boy wouldn't be so officious; but perhaps he's right!

Tred. Ho, indeed! Well, another time, Mr. Hundershell, if you require information about parties staying with Us, p'r'aps you'll be good enough to apply to me personally, instead of picking it up in some 'ole and corner fashion. (Undershell controls his indignation with difficulty.) To return to the individual in question, Miss Phillipson, I should have said myself he was something in the artistic or littery way; he suttingly didn't give me the impression of being a Gentleman.

Phill. (to herself, relieved). Then it isn't my Jem! I might have known he wouldn't be visiting here, and carrying on with Lady Rhodas. He'd never forget himself like that—if he has forgotten me!

Stept. It strikes me he's more of a sporting character, Tredwell. I know when I was circulating with the cigarettes, and so on, in the hall just now, he was telling the Captain some anecdote about an old steeplechaser that was faked up to win a Selling Handicap, and it tickled me to that extent I could hardly hold the spirit-lamp steady!

Tred. I may be mistook, Steptoe. All I can say is, that when me and James was serving cawfy to the ladies in the drawing-room, some of them had got 'old of a little pink book all sprinkled over with silver cutlets, and, rightly or wrongly, I took it to 'ave some connection with 'im.

Und. (excitedly). Pink and silver! Might I ask—was it a volume of poetry, called—er—Andromeda?

Tred. (crushingly). That I did not take the liberty of inquiring, Sir, as you might be aware if you was a little more familiar with the hetiquette of good Serciety.

[Undershell collapses; Mr. Adams enters, and steps into the chair vacated by the Chef, next to Mrs. Pomfret, with whom he converses.

Und. (to himself). To think that they may be discussing my book in the drawing-room at this very moment, while I—I—— (He chokes.) Ah, it won't bear thinking of! I must—I will get out of this cursed place! I have stood this too long as it is! But I won't go till I have seen this fellow Spurrell, and made him give me back my things. What's the time?... Ten! I can go at last. (He rises.) Mrs. Pomfret, will you kindly excuse me? I—I find I must go at once.

Mrs. Pomfr. Well, Mr. Undershell, Sir, you're the best judge; and, if you really can't stop, this is Mr. Adams, who'll take you round to the stables himself, and do anything that's necessary. Won't you, Mr. Adams?

Adams. So you're off to-night, Sir, are you? Well, I'd rather ha' shown you Deerfoot by daylight, myself; but there, I dessay that won't make much difference to you, so long as you do see the 'orse?

Und. (to himself). So Deerfoot's a horse! One of the features of Wyvern, I suppose; they seem very anxious I shouldn't miss it. I don't want to see the beast; but I daresay it won't take many minutes; and, if I don't humour this man, I shan't get a conveyance to go away in! (Aloud.) No difference whatever—to me. I shall be delighted to be shown Deerfoot; only I really can't wait much longer; I—I've an appointment elsewhere!

Adams. Right, Sir; you get your 'at and coat, and come along with me, and you shall see him at once.

[Undershell takes a hasty farewell of Miss Phillipson and the company generally—none of whom attempts to detain him—and follows his guide. As the door closes upon them, he hears a burst of stifled merriment, amidst which Miss Phillipson's laughter is only too painfully recognisable.

[It is proposed to form a "Trust for the Preservation of Beautiful or Historical Places."]

ENHANCED VALUE.

'Arry. "What sort of a Job's that you've got at Babel Buildings, Alf?"

Alf. "Jolly 'ard; all the Messages and Parcels from the top of the 'Ouse to the Basement go through me; and I'm only getting Thirty Bob a Week!"

'Arry. "Tell yer what, old Man, you'd command double the Money if you was fitted up with a Lift and a Speakin' tube!"

Sir,—I have seen some letters in the Daily Graphic on the above subject. A much more curious thing happened to me on April 1, 1887, at twenty-five minutes past ten in the morning. I dropped a pin about four yards from the south-western corner of the Marble Arch. It is almost incredible that exactly three years later I picked up a pin, at 4.17 in the afternoon, three yards and seven and a quarter inches to the south-east of the Humane Society's Receiving House. I have studied carefully the levels of the ground, the flow of the surface water, and the direction of the prevailing air currents, and I am reluctantly forced to the conclusion that it was not the same pin. Had it been, I should have found it five and a half inches further north. The question now is, whose pin was it?—Your obedient servant,

Dear Sir,—Some weeks ago I rode outside an omnibus from Piccadilly Circus to Charing Cross. Getting down hastily, when I found that it went on to Westminster instead of the City, I left behind a large grey parrot in a cage, a siphon of soda-water, and a St. Bernard dog. Yesterday, when I climbed on to an omnibus following the same route, I found my cage, my siphon, and my dog! It was the same omnibus, and the faithful beast was still there. Unfortunately the parrot and the soda-water were not, for the sagacious animal had evidently made use of them to sustain life, not very satisfactorily, for he was a mere skeleton.

Dear Mr. Punch,—Last evening I went out to dinner, and put my one latch-key in my pocket. Marvellous to relate, on my return home at three A.M., I took it, as I thought, from my pocket, and found that it had become two!

"EHEU FUGACES——"

And have you met my Friend Lily Macpherson in Glasgow? How Pretty we thought her!

"Pretty, Grandmamma! Why, she's as Fat as can be, and red-faced, and no Teeth!" "Ah well! Forty Years do change a Girl!"

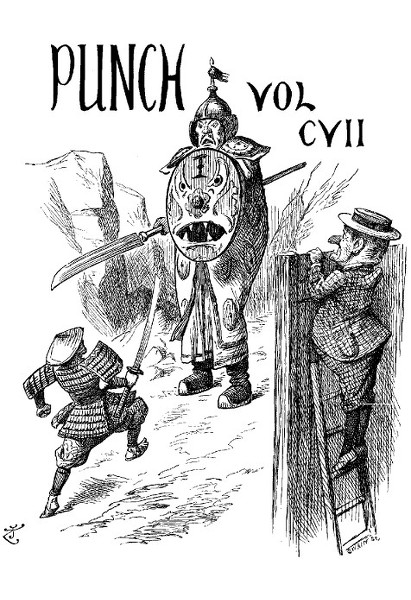

(Fragment of a Tale of New Japan as told around a Fire-Brazier in Dai Nippon.)

Once upon a time in the Happy Dragon-fly shaped Land of the Rising Sun there lived a little hero named Jap. Small he was, but valiant as Také-no-uchi-no-sukuné himself of the long life and many-syllabled name. He was a dead hand at dragon slaying, and had killed more tigers than Hadésu. He could exorcise Oni like one o'clock, these demons or imps having an exceeding bad time of it when Jap was, as he would term it, "on the job." In fact, his exploits were the favourite topic of talk when young and old gathered around the hibachi, or fire-braziers, to list to tales of heroism, filial piety, and Pro-Gress. Pro-Gress was the name of the great new goddess of whom Jap was a votary. From her he had received the gift of a new "sword of sharpness," which would not only, like the gift of the triple-headed Cornish giant, "cut through anything," but would make all enemies cut like anything.

Little Jap, having acquired this wonderful sword, compared with which that which Nitta threw into the sea was a mere oyster-knife, was naturally desirous of using it. He kept it as sharp as that of the great demon-queller Shō-ki; but the demons he quelled with it were the great obstructive ogres known as Kon-serva-tism, Fogi-ism and Pre-ju-dice. Jap gave those antiquated bogies beans. The Tengus and Shō-jos had a bad time of it, you bet, and the "bag" of Dragons, or Tatsus, Jap could show after one of his regular "battues" was a caution to Saurians, I can assure you! He had a collection of Tatsu-teeth that would have aroused the envy of Cadmus, and given Jason a high-toned job. As to that terrible wild-fowl, the Ho-ho bird, with "the head of a pheasant, the beak of a swallow, the neck of a tortoise, and the outward semblance of a dragon," Jap, with his "gun of swiftness" (another gift of his favourite goddess) knocked the Ho-hos over right and left, as though they were really pheasants in a swell British preserve; and it was commonly said that when Jap had a day among the Ho-hos, there was a glut in the Toyoakitsu poultry market for a fortnight after.

But Jap, in time, grew tired of the common or cherry-garden Ho-ho, and aweary of such small sport as mere dragons and demons could furnish. He yearned like an Anglo-Indian Shikari for big game!

Now there was an ugly, but enormous giant, fierce-looking as Kaminari, the Thunder-god, old as Urashima, the Kami-no-kuni Rip Van Winkle, strong as Asaina Saburō, the Dai Nippon Hercules, big as Fusi-yama, "the matchless mountain," rich as the Treasure Ship, laden with Ta-kara-mono (or "Precious Things"), stubborn, stolid, and unprogressive as Kamé, the hairy-tailed tortoise, himself. This tremendous Tartar-Mongolian Blunderbore had a number of fine names, of flowery flavour and Celestial swaggersomeness, but we will call him Jon-ni, for short.

Now Little Jap hated Big Jon-ni, and Big Jon-ni disdained Little Jap, as indeed he disdained everybody else save his conceited and colossal self. Jap curled his lip at Jon-ni; Jon-ni put out his tongue at Jap like a China figure; when the duodecimo hero bit his thumb at the elephantine Celestial, the elephantine Celestial cocked a snook at the duodecimo hero. This could not last. Little Jap was ambitious to try his sword of sharpness and his gun of swiftness upon big game. He cried, "By the heroic Hidésato who slew the giant Centipede, I will have a slap at this bouncing Bobadil of a wooden-headed, grandmother-worshipping, old Stick-in-the-mud!"

Some of his more timid friends tried to dissuade him. "Beware, Jap," they cried, "this Chinese Blunderbore is too big for thee!" "Pooh!" retorted the undaunted Jap. "Remember ——'the valiant Cornishman Who slew the giant Cormoran.' Am I not as big as Jack now, and as fit to play the Giant-killer as he? Too big? Why, the overgrown monster is like the Buddhist Daruma, who, 'arriving in China in the sixth century, at once went into a state of abstraction, which extended over nine years, during which time he never moved; and as a result lost the use of his legs.' Only Jon-ni has been 'in a state of abstraction' for nine centuries instead of nine years, and has lost the use of his head, as well as his legs! He hates and scorns my tutelary goddess, Pro-Gress. I will try the effect of her gifts upon him! Here goes!!!"

His admiring friends dubbed him "Jap the Giant-Killer" at once. And, indeed, when he "went for" that clumsy Colossus, who in physical proportions out-Chang'd Chang himself, the result of the first round, in which the swaggersome Jon-ni was fairly beaten to his knees, seemed to justify the title. But giants are not usually "knocked out" in one round, and—well, my children, tiny Jap's further fortunes in his fight with Titan Jon-ni, may furnish material for further narrative when next we gather around the glowing hibachi to tell tales of Jap the Giant-Killer! 151

152

153

AFTER THE BALL.

He. "How can I ever repay you for that delightful Waltz, Miss Golightly?"

She (whose train has suffered). "Oh, don't repay me. Settle with my Dressmaker!"

The Street. Saturday Night.

(By an Eye-witness.)

(In the Off Season.)

(Supposed to have been "written in Mid-Channel." See published Works of Alfr-d A-st-n.)

I.

II.

III.

THE PROFESSOR OF THE PERIOD.

154

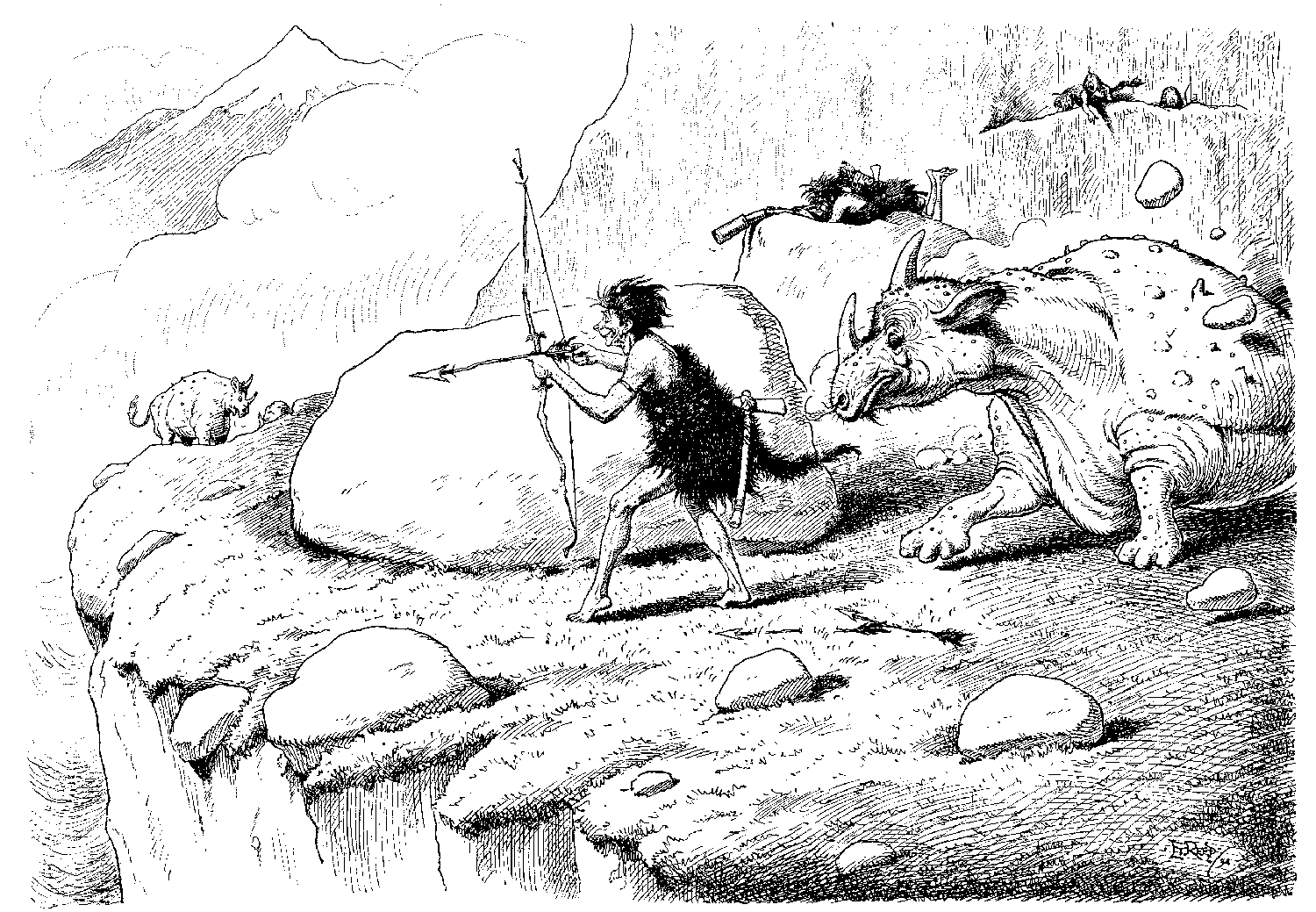

PREHISTORIC PEEPS.

There were often Unforeseen Circumstances which gave to the Highland Stalking of those days an added zest! 155

(An Unlucky Batsman's Lament after a Season of Slow Wickets.)

Air—"Ask me no more."

(A Story of the Long Vacation.)

"Mr. Briefless," said an eminent solicitor to me the other day, "I want you to go to East Babbleton, in Guiltshire, to see if the Great Gooseberry Will case is still open. It is a matter of vital importance, and I shall be glad if you can attend to it to-morrow."

Referring to Portington, I found that my diary was clear for the day specified, and I expressed my willingness to carry out my client's instructions.

"I must know at once," continued the gentleman, "because I desire to bring the matter before the Vacation Judge on an originating summons. I need scarcely add, that you will get the fullest particulars from the parish clerk."

Although rather imperfectly instructed, I determined to visit East Babbleton. The usual sources of railway information led me to believe that the place was six or seven miles distant from Nearvices in Guiltshire. I determined to go to Nearvices, taking with me my two lads (home for the holidays), George Lewis Herschell and Edward Clarke Russell. Before now I have explained that my sons' Christian names have been selected with a view to assisting (in after years) their professional advancement. We had to start at an unusually early hour from London, and after enjoying the companionship of some sportsmen, who talked about "duck" and "roots" for a quarter of a day, arrived at Nearvices at eleven o'clock. I made at once for the Red Lion, the principal hotel in the town. My sons followed me, eager for breakfast. Until then, they had satisfied their appetite by the stealthy consumption of about half-a-pound of a sweetmeat that is, I believe, known as Japanese Almond Rock.

The "Red Lion" was in a state of great commotion. There were people in high hats at the door, people in high hats looking out of the coffee-room window, people in high hats thronging the hall. With some trouble my lads and I got our breakfast, then I asked for the ostler. He came to me after a pause and awaited my orders.

"I want a trap to take me over to East Babbleton," I said; "and should like to know how much it will cost."

"Very sorry, Sir, but, I can't do it for you. All the carriages in the house are hired. You know, Sir, Miss Smith is going to be married, and consequently you can't get a conveyance for love or money."

I was seriously annoyed, as the instructions of my client were explicit.

"I really must get over," I said emphatically; "surely Miss Smith can lend us one of her carriages. You might ask her future husband."

"Can't do that. Sir," replied the ostler; "for we none of us know him. However, I'll see what can be done for you. Could you drive yourself over?"

"Oh, do Papa," shouted my two sons in an ecstasy of delight. "It would be such fun! and mother isn't here to stop you."

"Well, I will have a shot at it," I returned; "although truth to tell I am a little rusty. I have not driven for some time."

The ostler eyed me rather sharply, and retired. I then thought it my duty to reprove my sons for their ill-timed levity, explaining that their tomfoolery might have caused the ostler to refuse to entrust his equipage to my care.

"But you have never driven in your life?" said George Lewis Herschell. "Have you, Papa?"

"I cannot say that I have," I replied, with that truthfulness which is the characteristic of my dealings in the domestic circle.

"Oh, what a game!" shouted Edward Clarke Russell, roaring with laughter.

Severely chiding my offspring, I proceeded to the hall door. The ostler had been as good as his word. There was certainly a conveyance.

"It is not very showy, Sir," said the proprietor; "but I think it will last a dozen of miles or so."

It was a small dog-cart, which conjured up visions of the toy waggon-and-horse department in the Lowther Arcade. There was a horse in the shafts. The harness was imperfect, and the collar showed its straw. However, I took my seat, and the boys got up beside me. Then, amidst the good wishes of the wedding party watching our progress, I started. The horse immediately took up a course over the pavement, and no doubt aware that the illuminating power at East Babbleton was primitive, attempted to carry with him a lamp-post. We cannoned off the pavement into the middle of the road, and were fairly "off."

"If you boys laugh any more," I said, with the utmost severity, "I will turn you out and leave you."

"But Papa, if mother could only see us!" cried the pair, and then they indulged in apparently unextinguishable bursts of merriment.

I had no further time for remonstrance, as the brute of a horse, after beginning in a trot, had suddenly quickened its pace to a mad gallop. And as it did this I noticed that a dust-cart was just in front of us. I dragged at the reins, and with almost superhuman exertions brought the beast to a full stop.

"Which is the way to East Babbleton?" I asked, to explain my rather abrupt pull-up. "Am I taking the right road?"

The dustman looked at me, at the horse, smiled, and answered in the affirmative. Seeing that we were now about to descend a hill, I got down and led the horse by its bridle. The brute resented the 156 attention. So far as I could judge, without being an expert in horse-flesh, it seemed to me to be suffering from tooth-ache. It shook its head when I touched it, and appeared to be disinclined to go further.

"Do get in, Papa," said Edward Clarke Russell. "Perhaps he will go all right if you leave him alone."

Adopting my son's advice, I mounted the cart, and once again jerked the reins. The beast began at a trot, and then, as before, commenced a mad gallop. We rapidly left Nearvices behind us, and brought ourselves to a stop in front of a haystack.

"You see," I said, "the brute is open to reason. It was stopped by an obstruction. Seeing the futility of further progress, it desisted in its running."

"But look, Papa, at that," cried George Lewis Herschell, pointing to what seemed to be the remains of a coal cart. The wheels were off, the black diamonds were scattered about in all directions, and the shafts were broken.

"Was that an accident?" I asked an old man who was lighting his pipe. The venerable individual paused, looked at the pipe, looked at the pieces of the cart, and looked at me. Then he rubbed the right side of his head with the palm of his right hand.

"Well, yes, it was," he admitted, in an accent I cannot reproduce; but added, in a tone that suggested that mishaps of a similar character occurred on the average every five minutes; "but that accident happened near an hour ago."

This intelligence rather damped my ardour, and I immediately got off the cart and insisted upon leading the brute down the next hill. The animal protested, and shook its head. Remembering its possible tooth-ache, I treated it with increased courtesy, telling it to "Gee-up" and "be a good horse." I am sorry to say that the creature did not seem inclined to acknowledge my kindness.

Having come to a level piece of road, I once more mounted into the Lowther Arcade dog-cart, and urged on my partially wild career. I had passed a four-winged post at cross roads, and had followed the sign pointing to "Babbleton." I had got safely up to a farm-house, having restrained en route an inclination on the part of my horse to commit suicide by jumping over the parapet of a bridge into a small mountain torrent.

"Is this the way to East Babbleton?" I asked a rather cheery, rosy-cheeked dame, who had been watching our manœuvres with a kindly smile, not entirely exempt from good-natured apprehension.

"No, this is not the road, Master," she returned, in the same unapproachable dialect. "You ought to have borne to the left when you came to the cross-roads."

Seeing that I had to go back, I seized each of the reins and called upon my beast of a horse to make an effort. The noble animal answered bravely to the call, and managed to turn round on a space of turf about the size of a waggon wheel. It was really a very clever performance, and had it been seen by Mr. Ritchie, I fancy would have secured for us a lucrative engagement for a "side show" at the Royal Westminster Aquarium.

"Well, that was a shave surely," said the dame of the cheery countenance; "when I saw your off wheel go up in the air and hang over the ditch I thought it would be all up with ye."

Accepting the compliment with dignified geniality, I asked our fair critic if she could bait our horse.

"Well, I can give him a handful of hay," said the lady; "but I would not take him out of the shafts for worlds. If I untied him I could not put him together again."

Refreshed by the nourishment, our steed started again, and after retracing our steps and nearly upsetting a hay cart, and narrowly running down a pig, we reached East Babbleton in fairly good condition. I looked at my watch and found that we had done the six miles in two hours and a quarter. Having transacted my business, I now turned the nose of my steed homewards. I had noticed with some alarm that I had only an hour to get back to Nearvices if I wanted to catch the train for London. This being so, I saw it was absolutely necessary that I should act with decision. I held a council of war with my two sons, and we came to the conclusion that we must get back as fast at we could, and when there was a difficulty, risk it. We entered our conveyance and started.

I shall never forget the experience. It was absolutely delightful. Giving Flora (I came to the conclusion that my steed with the tooth-ache must have been called Flora) her head, I urged her to progress as rapidly as possible. The mare promptly answered to the call. I said "chick," and she started off at a mad gallop. We absolutely flew up-hill, down-hill, and would no doubt have entered "my lady's chamber" had not the adjoining cottages been occupied by rustics. At our approach children, ducks, dogs and gipsies fled in terror. We boldly cannoned against waggons and shook milestones to their very foundations. I had long since forgotten my nervousness, and had assumed an air that would have been becoming in an individual nicknamed (let us say) "down the road Billy."

I urged Flora to "gee up," by suggesting that "five o'clock tea" was waiting for her on her arrival at Nearvices. My two sons, George Lewis Herschell and Edward Clarke Russell, also rendered valuable assistance by waving their straw hats, and singing comic songs with a vehemence that rendered the ballads undistinguishable from war ditties. As we entered Nearvices, Flora stumbled, and all but fell. However, with wonderful skill, I picked her up at the end of my reins, and urged her to fresh exertions by a feeble flick of the whip, that expended its force on the shafts and a part of the collar. Again we flew on. We renewed our acquaintance with the attractive lamp-post, we crossed the sharp curve of the familiar pavement, we collided against the monument to a worthy in the market-place, and drove up with a jerk in front of the "Red Lion." I looked again at my watch; we had done the six miles in twenty-two minutes. Considering the hills, dales, and obstructive milestones, a very fair record.

"What, you have come back!" exclaimed the landlady of the "Red Lion." "Why, we never expected to see you."

I found subsequently that the wedding party, after watching our departure, had taken bets about our probable return. The most popular wager seemed to be that we should reappear after midnight with a wheel, a bit of harness, and the whip, but without the quadruped.

I have nothing further to relate save this. That after my recent success I am thinking seriously of giving up the Bar and taking to the road. If I can raise the required capital, I think I shall run a four-horse coach between the Temple and Turnham Green. Both my boys are anxious to give up their school to act as my guard.

By the way, I may add in conclusion that the parish clerk of East Babbleton declared that he had never heard (until I mentioned it) of the Great Gooseberry Will Case. So I suppose that my client must have been wrong in his details.

Pump-Handle Court,

September 22, 1894.

(Signed)

A. Briefless, Junior.

SELF-EVIDENT.

The Colonel. "What was that noise I heard just now?"

His Nephew. "Oh! I was blowing up my Servant!"

The Colonel. "May I ask why?"

His Nephew. "Well—aw—you see he is such a confounded Idiot!"

The Colonel. "But did it never occur to you that if he weren't such a confounded Idiot he would never have been your Servant?"

THE CUT DIRECT.

Scene—A Norfolk Beach.

Mr. and Mrs. Wavely (returning to their tent). "Ah, Mr. McVicar! You remember meeting us at Pitlochrie last Autumn, don't you?"

Mr. McVicar. "I recollect your Faces perfately well, Sir; but ye'll excuse me obsairvin' that the praisent circumstances are verra, verra different!"

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation are as in the original.