STELLAR ATMOSPHERES

HARVARD OBSERVATORY MONOGRAPHS

HARLOW SHAPLEY, EDITOR

No. 1

A CONTRIBUTION TO THE OBSERVATIONAL STUDY OF HIGH TEMPERATURE IN THE REVERSING LAYERS OF STARS

BY

CECILIA H. PAYNE

PUBLISHED BY THE OBSERVATORY

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

1925

COPYRIGHT, 1925

BY HARVARD OBSERVATORY

PRINTED AT THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASS., U.S.A.

[Pg v]

THE most effective way of publishing the results of astronomical investigations is clearly dependent on the nature and scope of each particular research. The Harvard Observatory has used various forms. Nearly a hundred volumes of Annals contain, for the most part, tabular material presenting observational results on the positions, photometry, and spectroscopy of stars, nebulae, and planets. Shorter investigations have been reported in Circulars, Bulletins, and in current scientific journals from which Reprints are obtained and issued serially.

It now appears that a few extensive investigations of a somewhat monographic nature can be most conveniently presented as books, the first of which is the present special analysis of stellar spectra by Miss Payne. Other volumes in this series, it is hoped, will be issued during the next few years, each dealing with a subject in which a large amount of original investigation is being carried on at this observatory.

The Monographs will differ in another respect from all the publications previously issued from the Harvard Observatory—they cannot be distributed gratis to observatories and other interested scientific institutions. It is planned, however, to cover a part of the expenses of publication with special funds and to sell the volumes at less than the cost of production.

The varied problems of stellar atmospheres are particularly suited to the comprehensive treatment here given. They involve investigations of critical potentials, spectral classification, stellar temperatures, the abundance of elements, and the far-reaching theories of thermal ionization as developed in the last few years by Saha and by Fowler and Milne. Some problems of special interest to chemists and physicists are considered, and subjects intimately bound up with inquiries concerning stellar evolution come under discussion.

[Pg vi]

The work is believed to be fairly complete from the bibliographic standpoint, for Miss Payne has endeavored throughout to give a synopsis of the relevant contributions by various investigators. Her own contributions enter all chapters and form a considerable portion of Parts II and III.

It should be remembered that the interpretation of stellar spectra from the standpoint of thermal-ionization is new and the methods employed are as yet relatively primitive. We are only at the beginning of the astronomical application of the methods arising from the newer analyses of atoms. Hence we must expect (and endeavor to provide) that a study such as is presented here will promptly need revision and extension in many places. Nevertheless, as it stands, it shows the current state of the general problem, and will also serve, we hope, as a summary of past investigations and an indication of the direction to go in the immediate future.

In the course of her investigation of stellar atmospheres, Miss Payne has had the advantage of conferences with Professors Russell and Stewart of Princeton University and Professor Saunders of Harvard University, as well as with various members of the Harvard Observatory staff.

The book has been accepted as a thesis fulfilling the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Radcliffe College.

H. S.

MAY 1, 1925.

[Pg vii]

| PART I | |

| THE PHYSICAL GROUNDWORK | |

| I. THE LABORATORY BASIS OF ASTROPHYSICS | 3 |

| Relation of physics to astrophysics. Properties of matter associated with nuclear structure. Arrangement of extra-nuclear electrons. Critical potentials. Duration of atomic states. Relative probabilities of atomic states. Effect on the spectrum of conditions at the source. (a) Temperature class. (b) Pressure effects. (c) Zeemann effect. (d) Stark effect. |

|

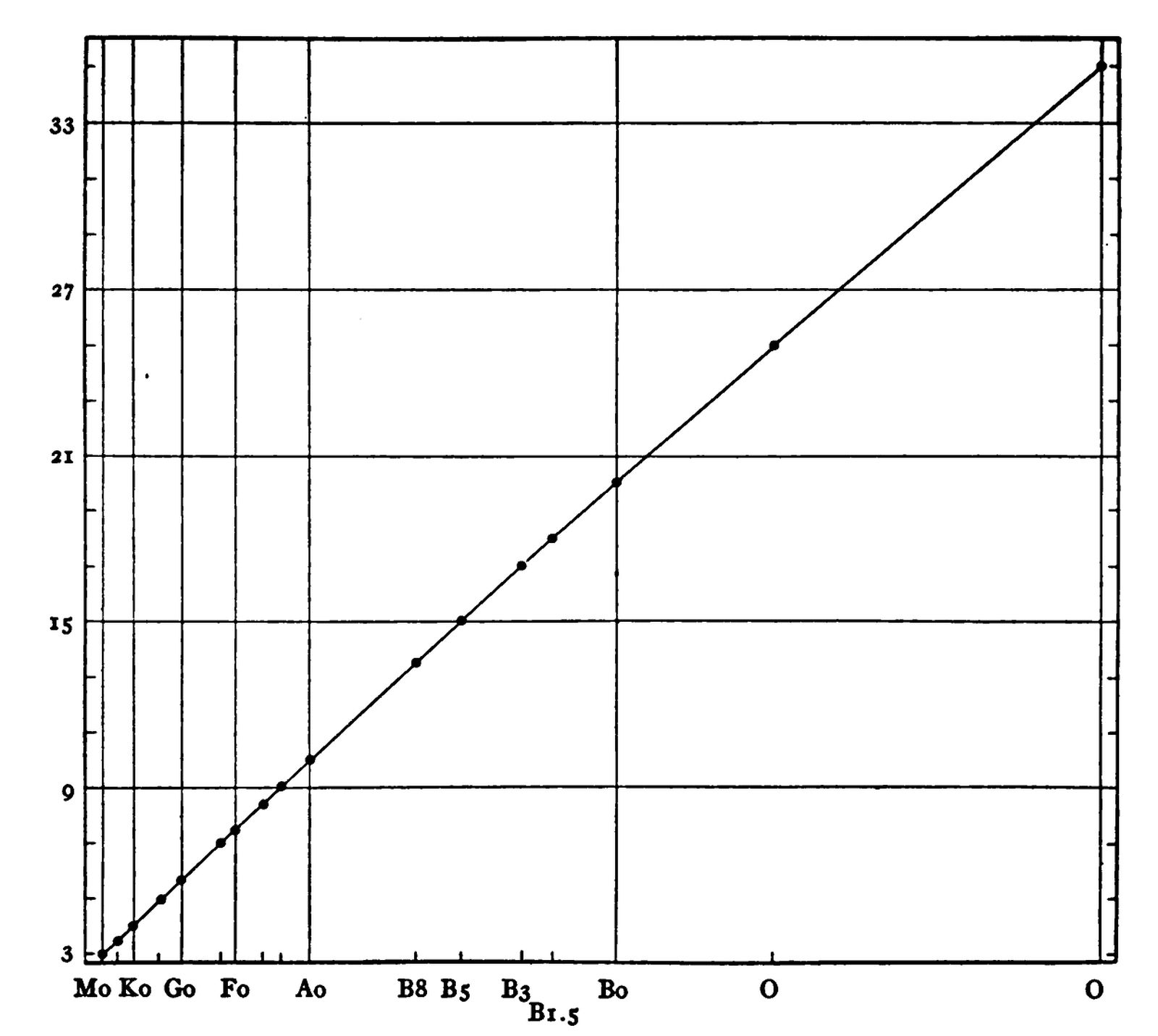

| II. THE STELLAR TEMPERATURE SCALE | 27 |

| Definitions. The mean temperature scale. Temperatures of individual stars. Differences in temperature between giants and dwarfs The temperature scale based on ionization. |

|

| III. PRESSURES IN STELLAR ATMOSPHERES | 34 |

| Range in stellar pressures. Measures of pressure in the reversing layer. (a) Pressure shifts of spectral lines. (b) Sharpness of lines. (c) Widths of lines. (d) Flash spectrum. (e) Equilibrium of outer layers of the sun. (f) Observed limit of the Balmer series. (g) Ionization phenomena. |

|

| IV. THE SOURCE AND COMPOSITION OF THE STELLAR SPECTRUM | 46 |

| General appearance of the stellar spectrum. Descriptive definitions. The continuous background. The reversing layer. Emission lines. |

|

| V. ELEMENTS AND COMPOUNDS IN STELLAR ATMOSPHERES | 55 |

| Identifications with laboratory spectra. Occurrence and behavior of known lines in stellar spectra. [Pg viii] |

|

| PART II | |

| THEORY OF THERMAL IONIZATION | |

| VI. THE HIGH-TEMPERATURE ABSORPTION SPECTRUM OF A GAS | 91 |

| The schematic reversing layer. The absorption of radiation. Low temperature conditions. Ultimate lines. Ionization. Production of subordinate lines. Lines of ionized atoms. Summary. |

|

| VII. CRITICAL DISCUSSION OF IONIZATION THEORY | 105 |

| Saha’s treatment—marginal appearance. Theoretical formulae. Physical constants required by the formulae. Assumptions necessary for the application. Laboratory evidence bearing on the theory. (a) Ultimate lines. (b) Temperature classes. (c) Furnace experiments. (d) Conductivity of flames. Solar intensities as a test of ionization theory. |

|

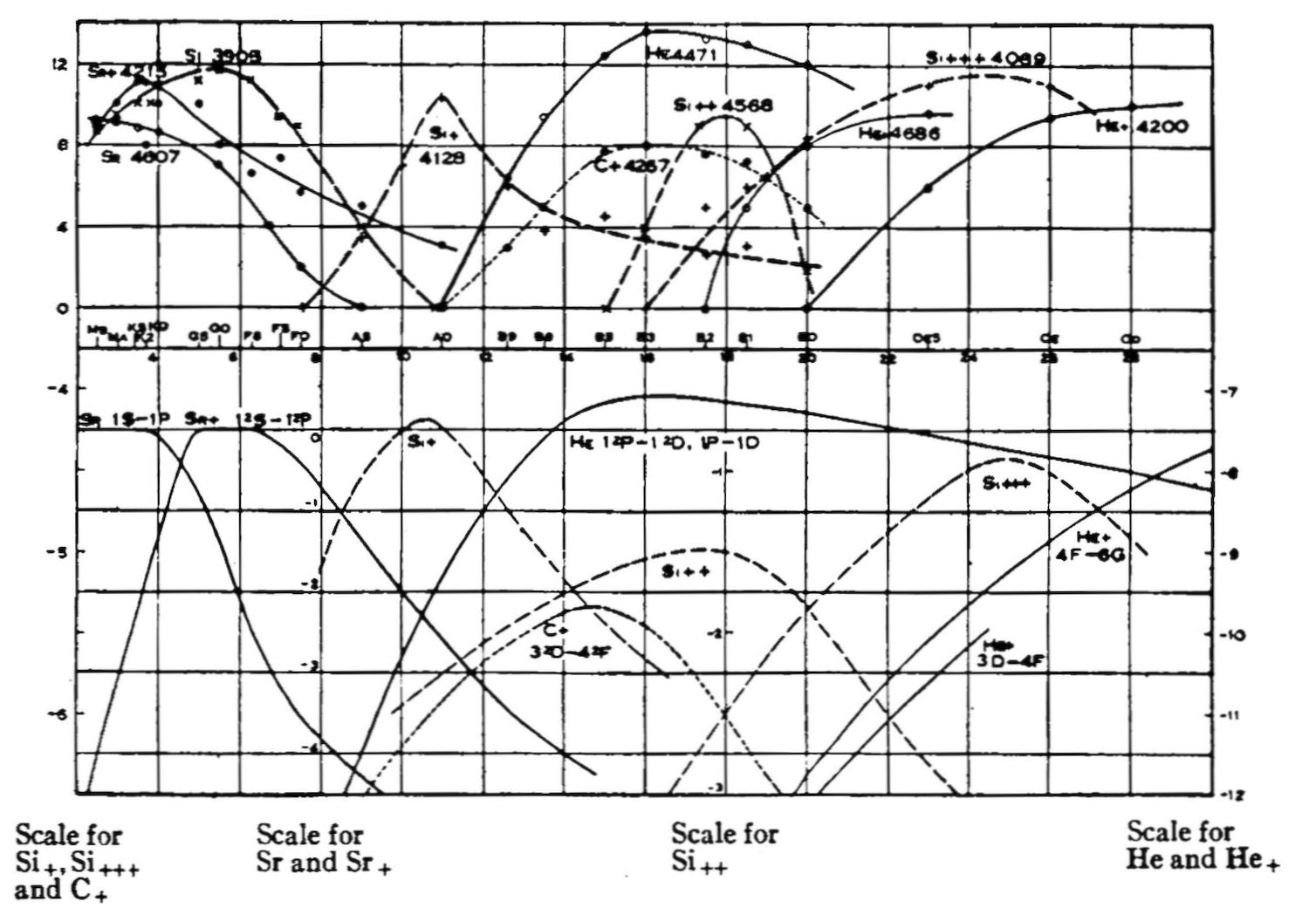

| VIII. OBSERVATIONAL MATERIAL FOR THE TEST OF IONIZATION THEORY | 116 |

| Measurement of line intensity. Method of standardization. Summary of results. Consistency of results. |

|

| IX. THE IONIZATION TEMPERATURE SCALE | 133 |

| Consistency of the preliminary scale. Effect of pressure. Levels of origin of ultimate and subordinate lines. Influence of relative abundance. Method of determining effective partial pressure. The corrected temperature scale. [Pg ix] |

|

| X. THE IONIZATION TEMPERATURE SCALE | 133 |

| PART III | |

| ADDITIONAL DEDUCTIONS FROM IONIZATION THEORY | |

| XI. THE ASTROPHYSICAL EVALUATION OF PHYSICAL CONSTANTS | 155 |

| Spectroscopic constants (Plaskett). Critical potentials (Payne). Duration of atomic states (Milne). |

|

| XII. SPECIAL PROBLEMS IN STELLAR ATMOSPHERES | 161 |

| Class Class The Balmer lines. Classification of Silicon and Strontium stars. Peculiar Class c-stars. |

|

| XIII. THE RELATIVE ABUNDANCE OF THE ELEMENTS | 177 |

| Terrestrial data. Astrophysical data. Uniformity of composition of stellar atmospheres. Marginal appearance. Comparison of stellar and terrestrial estimates. |

|

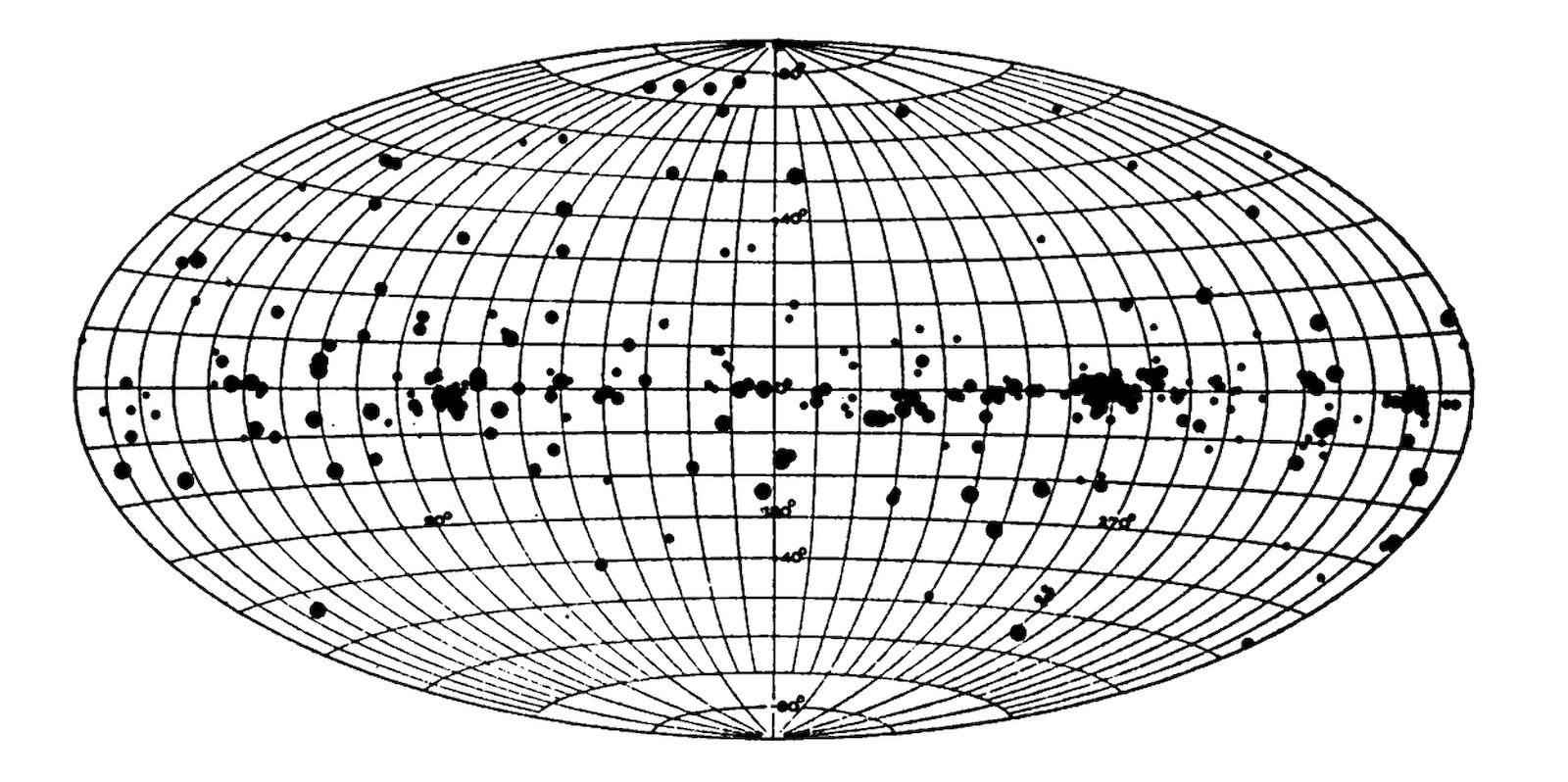

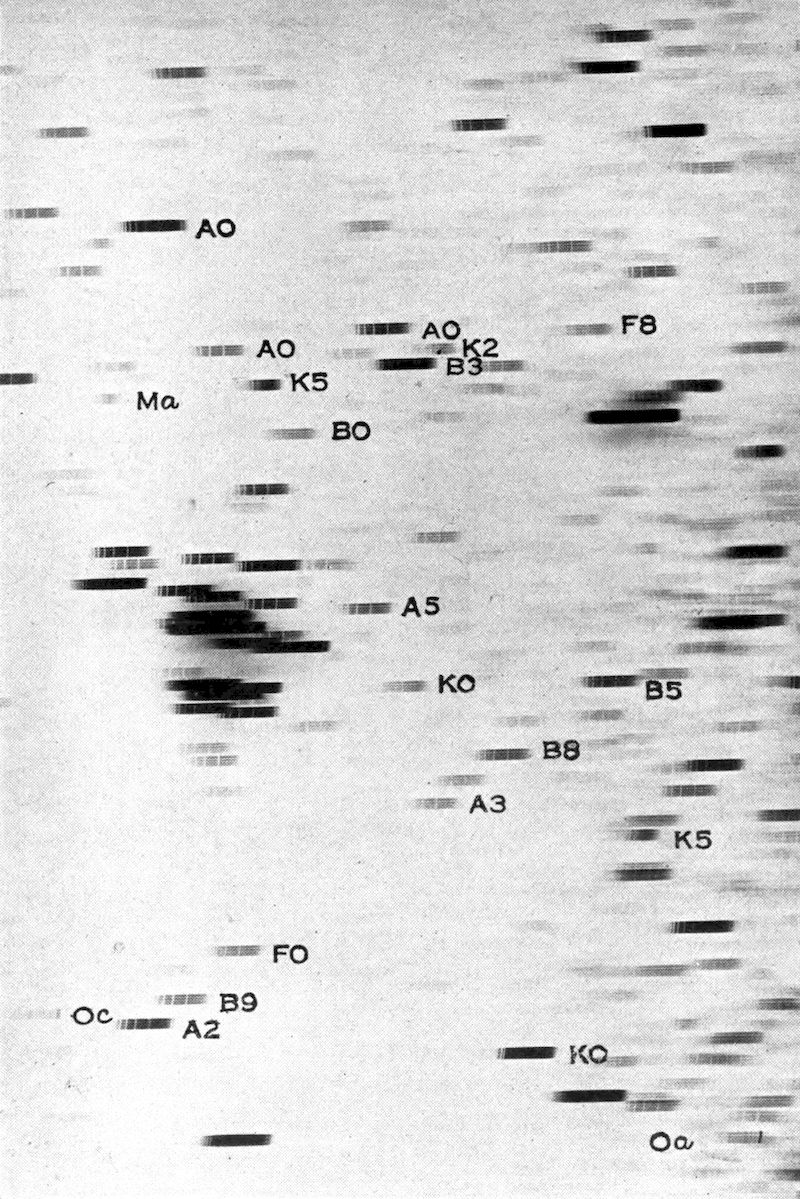

| XIV. THE MEANING OF STELLAR CLASSIFICATION | 190 |

| Principles of classification. Object of the Draper Classification. Method of classifying. Finer Subdivisions of the Draper Classes. Implications of the Draper system. Homogeneity of the classes. Spectral differences between giants and dwarfs. |

|

| XV. ON THE FUTURE OF THE PROBLEM | 199 |

| APPENDICES | |

| I. INDEX TO DEFINITIONS | 203 |

| II. SERIES RELATIONS IN LINE SPECTRA | 203 |

| III. LIST OF STARS USED IN CHAPTER VIII | 205 |

| IV. INTENSITY CHANGES OF LINES WITH UNKNOWN SERIES RELATIONS | 207 |

| V. MATERIAL ON A STARS, QUOTED IN CHAPTER XII | 208 |

| SUBJECT INDEX | 211 |

| NAME INDEX | 214 |

[Pg 3]

THE application of physics in the domain of astronomy constitutes a line of investigation that seems to possess almost unbounded possibilities. In the stars we examine matter in quantities and under conditions unattainable in the laboratory. The increase in scope is counterbalanced, however, by a serious limitation—the stars are not accessible to experiment, only to observation, and there is no very direct way to establish the validity of laws, deduced in the laboratory, when they are extrapolated to stellar conditions.

The verification of physical laws is not, however, the primary object of the application of physics to the stars. The astrophysicist is generally obliged to assume their validity in applying them to stellar conditions. Ultimately it may be that the consistency of the findings in different branches of astrophysics will form a basis for a more general verification of physical laws than can be attained in the laboratory; but at present, terrestrial physics must be the groundwork of the study of stellar conditions. Hence it is necessary for the astrophysicist to have ready for application the latest data in every relevant branch of physical science, realizing which parts of modern physical theory are still in a tentative stage, and exercising due caution in applying these to cosmical problems.

The recent advance of astrophysics has been greatly assisted by the development, during the last decade, of atomic and radiation theory. The claim that it would have been possible to predict the existence, masses, temperatures, and luminosities of the stars from the laws of radiation, without recourse to stellar observations, represents the triumph of the theory of radiation. It is equally true that the main features of the spectra of the stars could be predicted from a knowledge of atomic structure and the origin of spectra. The theory of [Pg 4] radiation has permitted an analysis of the central conditions of stars, while atomic theory enables us to analyze the only portion of the star that can be directly observed—the exceedingly tenuous atmosphere.

The present book is concerned with the second of these two problems, the analysis of the superficial layers, and it approaches the subject of the physical chemistry of stellar atmospheres by treating terrestrial physics as the basis of cosmical physics. From a brief working summary of useful physical data (Chapter I) and a synopsis of the conditions under which the application is to be made (Chapters II and Chapter III), we shall pass to an analysis of stellar atmospheres by means of modern spectrum theory. The standpoint adopted is primarily observational, and new data obtained by the writer in the course of the investigation will be presented as part of the discussion.

The first chapter contains a synopsis of the chief data which bear on atomic structure—the nuclear properties, and the disposition of the electrons around the nucleus. The origin of line spectra is discussed, and the ionization potentials corresponding to different atoms are tabulated. Lastly a brief summary is made of the effect of external conditions, such as temperature, pressure, and magnetic or electric fields, upon a line spectrum.

ATOMIC PROPERTIES ASSOCIATED WITH THE NUCLEUS

The properties determined by the atomic nucleus are the mass, and the isotopic and radioactive properties. The astrophysical study of these factors is as yet in an elementary stage, but it seems that all three have a bearing on the frequency of atomic species, and that future theory may also relate them to the problem of the source and fate of stellar energy. Moreover, up to the present no general formulation of the theory of the formation and stability of the elements has been possible, and it is well to keep in mind the data which are apparently most relevant to the problem—the observational facts relating to the nucleus. Probably the study of the nucleus involves the most fundamental[Pg 5] of all cosmical problems—a problem, moreover, which is largely in the hands of the laboratory physicist.

The chief nuclear data are summarized in Table I. Successive columns contain the atomic number, the element and its chemical symbol, the atomic weight[1] and the mass numbers of the known isotopes,[2] the percentage terrestrial abundance,[3] expressed in atoms, and the recorded stellar occurrence. Presence in the stars is indicated by an asterisk, absence by a dash.

| No. | Element | Atomic Weight |

Isotopes | Percentage Terrestrial Abundance (Atoms) |

Stellar Occurrences |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydrogen | H | 1.008 | 1.008 | 15.459 | * |

| 2 | Helium | He | 4.00 | 4 | .. | * |

| 3 | Lithium | Li | 6.94 | 7, 6 | 0.0129 | * |

| 4 | Beryllium | Be | 9.01 | 9 | 0.0020 | — |

| 5 | Boron | B | 11.0 | 11, 10 | 0.0016 | — |

| 6 | Carbon | C | 12.005 | 12 | 0.2069 | * |

| 7 | Nitrogen | N | 14.01 | 14 | 0.0383 | * |

| 8 | Oxygen | O | 16.00 | 16 | 59.940 | * |

| 9 | Fluorine | F | 19.0 | 19 | 0.0282 | — |

| 10 | Neon | Ne | 20.0 | 20, 22, (21) | .. | — |

| 11 | Sodium | Na | 23.00 | 23 | 2.028 | * |

| 12 | Magnesium | Mg | 24.32 | 24, 25, 26 | 1.426 | * |

| 13 | Aluminium | Al | 27.1 | 4.946 | * | |

| 14 | Silicon | Si | 28.3 | 28, 29, 30 | 16.235 | * |

| 15 | Phosphorus | P | 31.04 | 31 | 0.0818 | — |

| 16 | Sulphur | S | 32.06 | 32 | 0.0518 | * |

| 17 | Chlorine | Cl | 35.46 | 35, 37, (39) | 0.1149 | — |

| 18 | Argon | A | 39.88 | 40, 36 | .. | — |

| 19 | Potassium | K | 39.10 | 39, 41 | 1.088 | * |

| 20 | Calcium | Ca | 40.07 | (40, 44) | 1.503 | * |

| 21 | Scandium | Sc | 44.1 | 45 | .. | * |

| 22 | Titanium | Ti | 48.1 | 48 | 0.2407 | * |

| 23 | Vanadium | V | 51.0 | 51 | 0.0133 | * [Pg 6] |

| 24 | Chromium | Cr | 52.0 | 52 | 0.0213 | * |

| 25 | Manganese | Mn | 54.93 | 55 | 0.0351 | * |

| 26 | Iron | Fe | 55.84 | 54, 56 | 1.485 | * |

| 27 | Cobalt | Co | 58.97 | 59 | 0.0009 | * |

| 28 | Nickel | Ni | 58.68 | 58, 60 | 0.0091 | * |

| 29 | Copper | Cu | 63.57 | 63, 65 | 0.0028 | * |

| 30 | Zinc | Zn | 65.37 | (64, 66, 68, 70) | 0.0011 | * |

| 31 | Gallium | Ga | 69.9 | 69, 71 | .. | — |

| 32 | Germanium | Ge | 72.5 | 74, 72, 70 | .. | — |

| 33 | Arsenic | As | 74.96 | 75 | .. | — |

| 34 | Selenium | Se | 79.2 | .. | — | |

| 35 | Bromine | Br | 79.92 | 79, 81 | .. | — |

| 36 | Krypton | Kr | 82.92 | 84, 86, 82, 83, 70, 78 |

.. | — |

| 37 | Rubidium | Rb | 85.45 | 85, 87 | .. | * |

| 38 | Strontium | Sr | 87.63 | 88, 86 | 0.0065 | * |

| 39 | Yttrium | Y | 88.7 | 89 | 0.0030 (with Ce) |

* |

| 40 | Zirconium | Z | 90.6 | 90, 92, 94 | 0.0095 | * |

| 41 | Niobium | Nb | 93.1 | .. | ? | |

| 42 | Molybdenum | Mo | 96 | .. | * | |

| 43 | .. | .. | .. | |||

| 44 | Ruthenium | Ru | 101.7 | .. | * | |

| 45 | Rhodium | Rh | 102.9 | .. | * | |

| 46 | Palladium | Pd | 106.7 | .. | * | |

| 47 | Silver | Ag | 107.88 | 107, 109 | .. | * |

| 48 | Cadmium | Cd | 112.40 | 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 116 |

.. | — |

| 49 | Indium | In | 114.8 | .. | — | |

| 50 | Tin | Sn | 118.7 | .. | ? | |

| 51 | Antimony | Sb | 120.2 | .. | — | |

| 52 | Tellurium | Te | 127.5 | 126, 128, 130 | .. | — |

| 53 | Iodine | I | 126.92 | 127 | .. | — |

| 54 | Xenon | Xe | 130.2 | 129, 132, 131, 134, 136, (128, 130) |

.. | — |

| 55 | Caesium | Cs | 132.81 | 133 | .. | * |

| 56 | Barium | Ba | 137.37 | 138 | 0.0098 | * |

| 57 | Lanthanum | La | 139.0 | 139 | .. | * |

| 58 | Cerium | Ce | 140.25 | 140, 142 | 0.0030 (with Y) |

* |

| 59 | Praseodymium | Pr | 140.9 | 141 | .. | —[Pg 7] |

| 60 | Neodymium | Nd | 144.3 | 142-150 | .. | — |

| 61 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 62 | Samarium | Sa | 150.4 | .. | — | |

| 63 | Europium | Eu | 152.0 | .. | * | |

| 64 | Gadolinium | Gd | 157.3 | .. | — | |

| 65 | Terbium | Tb | 159.2 | .. | * | |

| 66 | Dysprosium | Dy | 162.5 | .. | — | |

| 67 | Holmium | Ho | 163.5 | .. | — | |

| 68 | Erbium | Er | 167.7 | .. | — | |

| 69 | Thulium | Tm | 168.5 | .. | — | |

| 70 | Ytterbium | Yb | 173.5 | .. | — | |

| 71 | Lutecium | Lu | 175.0 | .. | — | |

| 72 | Hafnium | Hf | .. | — | ||

| 73 | Tantalum | Ta | 181.5 | .. | — | |

| 74 | Tungsten | W | 184.0 | .. | — | |

| 75 | .. | .. | — | |||

| 76 | Osmium | Os | 190.9 | .. | — | |

| 77 | Iridium | Ir | 193.1 | .. | — | |

| 78 | Platinum | Pt | 195.2 | .. | — | |

| 79 | Gold | Au | 197.2 | .. | — | |

| 80 | Mercury | Hg | 200.6 | (197, 198, 199, 200) 202, 204 |

.. | — |

| 81 | Thallium | Tl | 204.0 | .. | — | |

| 82 | Lead | Pb | 207.2 | 0.0002 | * | |

| 83 | Bismuth | Bi | 208.0 | .. | — | |

| 84 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 85 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 86 | Radon | Rd | 222.4 | .. | — | |

| 87 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 88 | Radium | Ra | 226.0 | .. | — | |

| 89 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 90 | Thorium | Th | 232.4 | .. | — | |

| 91 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 92 | Uranium | U | 238.2 | .. | [Pg 8]— | |

ARRANGEMENT OF EXTRA-NUCLEAR ELECTRONS

Logically a description of the analysis of spectra should precede the discussion of electron arrangement, for our knowledge of the extra-nuclear electrons is very largely based on spectroscopic evidence. The established conceptions of atomic structure, however, are useful in classifying mentally the general outlines of the origin of line spectra, and therefore, for convenience of reference, Bohr’s table[4] of the arrangement of extra-nuclear electrons is here prefixed to our brief discussion of spectroscopic data. The chemical elements are given in order of atomic number, and successive columns contain, for the atom in its normal state, the numbers of electrons in the various quantum orbits.

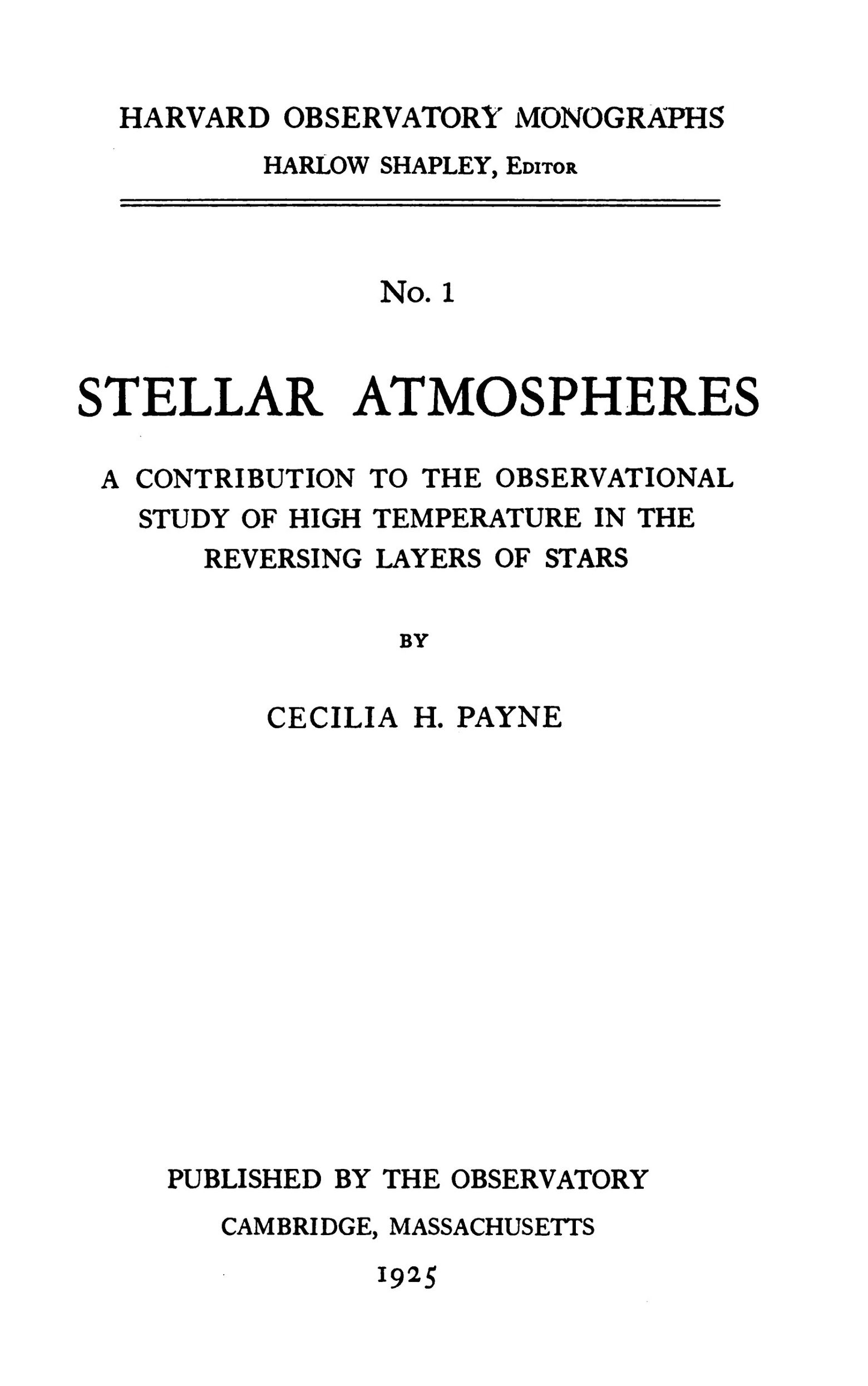

Figure 1

Arrangement of electron orbits for the atom of neutral sodium.

Orbits consisting partly of broken lines are circular orbits seen in

perspective. The numbers and quantum relations of the orbits are as

follows: inner shell, two orbits; next shell, four

orbits and four

orbits; outer electron

orbit.

In accordance with the notation of Bohr and Kramers,[5] the first figure in the orbit-designation that stands at the head of a column denotes the total quantum number, which determines the length of the major axis of the corresponding orbit. The subscript is the so-called azimuthal quantum number, which determines the ellipticity of the orbit; the orbits with the smallest azimuthal quantum numbers are the most eccentric, and those for which the azimuthal quantum number is [Pg 9] equal to the total quantum number are circular. The diagram (Figure 1) represents the normal arrangement of electrons around the nucleus of the sodium atom, which possesses eleven extra-nuclear electrons.

| No. | Elt. | 1₁ | 2₁ | 2₂ | 3₁ | 3₂ | 3₃ | 4₁ | 4₂ | 4₃ | 4₄ | 5₁ | 5₂ | 5₃ | 5₄ | 5₅ | 6₁ | 6₂ | 6₃ | 6₄ | 6₅ | 6₆ | 7₁ | 7₂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | He | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Li | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Be | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | B | 2 | 2 | (1) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | C | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | N | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | O | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | F | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Ne | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Na | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Mg | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Al | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Si | 2 | 4 | 4 | (2) | (2) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | P | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | S | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Cl | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | A | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | K | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | - | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | Ca | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | - | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 21 | Sc | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| 22 | Ti | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Cu | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 30 | Zn | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 31 | Ga | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 32 | Ge | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| 33 | As | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 34 | Se | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| 36 | Kr | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| 37 | Rb | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | - | - | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 38 | Sr | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | - | - | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 39 | Y | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | (2) | ||||||||||||

| 40 | Zr | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | - | (2) | [Pg 10] | |||||||||||

| 47 | Ag | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 48 | Cd | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 49 | In | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 50 | Sn | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 51 | Sb | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 52 | Te | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 53 | I | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||

| 54 | Xe | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 55 | Cs | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 4 | - | - | - | 1 | |||||||

| 56 | Ba | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 4 | - | - | - | 2 | |||||||

| 57 | La | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | - | (2) | |||||||

| 58 | Ce | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 4 | 4 | 2 | - | - | (2) | |||||||

| 59 | Pr | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | - | - | 1 | |||||||

| 71 | Lu | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | - | (2) | |||||||

| 72 | Hf | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | - | - | (2) | |||||||

| 79 | Au | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 1 | |||||||

| 80 | Hg | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 2 | |||||||

| 81 | Ti | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| 82 | Pb | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | (4) | |||||||

| 83 | Bi | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 4 | 1 | ||||||

| 86 | Rd | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| 88 | Ra | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 4 | 4 | - | - | - | - | 2 | |

| 89 | Ac | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | - | - | (2) | |

| 90 | Th | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | 4 | 4 | 2 | - | - | - | (2) | |

| 118 | ? | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | - | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | - | - | 4 | 4 |

The table also gives the number of spectroscopic valency electrons, a quantity which is required by the theory of thermal ionization. The spectroscopic valency electrons are those in equivalent outer orbits (outer orbits of equal total quantum number which have the same azimuthal quantum number). The number is not necessarily the same as the number of chemical valencies (the number of orbits with the same total quantum number) although the two values coincide for the alkali metals and for the alkaline earths. For carbon,[6] on the other [Pg 11] hand, the number of spectroscopic valency electrons is two (the number of 22 orbits), while the chemical valency, corresponding to the total number of 2-quantum orbits, is four.

THE PRODUCTION OF LINE SPECTRA

It is not proposed to discuss the theory of the origin of line spectra here in any detail. What is important from the astrophysical point of view is the association of known lines in the spectrum with different levels of energy in the atom, these levels representing definite electron orbits. Absorption and emission of energy take place in an atom by the transfer of an electron from an orbit associated with low energy to an orbit associated with high energy, and vice versa. The frequency of the light which is thus absorbed or emitted is expressed by the familiar quantum relation:

where

and

are the initial and final energies,

, and

is the frequency of the light absorbed or given out.

The atom absorbs from its environment the quanta relevant to the particular electron transfers of which it is capable at the time. These transfers are, of course, governed by the number and arrangement of the spectroscopic valency electrons, or in other words, by the state of ionization or excitation of the atom.

The unionized (or neutral) atom in the unexcited state absorbs the ultimate lines by the removal of one electron from its normal stationary state to some other which can be reached from that state, and re-emits them by the return of the electron to that state. The electron may, of course, leave the state to which it was carried by the ultimate absorption and pass to some state other than the normal one. If this final state is a state of higher energy than the previous state, the line produced by the process will be an absorption line; if [Pg 12] it is of lower energy the result will be the production of an emission line. In either case the line produced by the transfer of an electron from a stationary state other than the normal state is known as a subordinate line. The distinction between series of ultimate and subordinate lines is of great importance in the astrophysical applications of the theory of ionization.

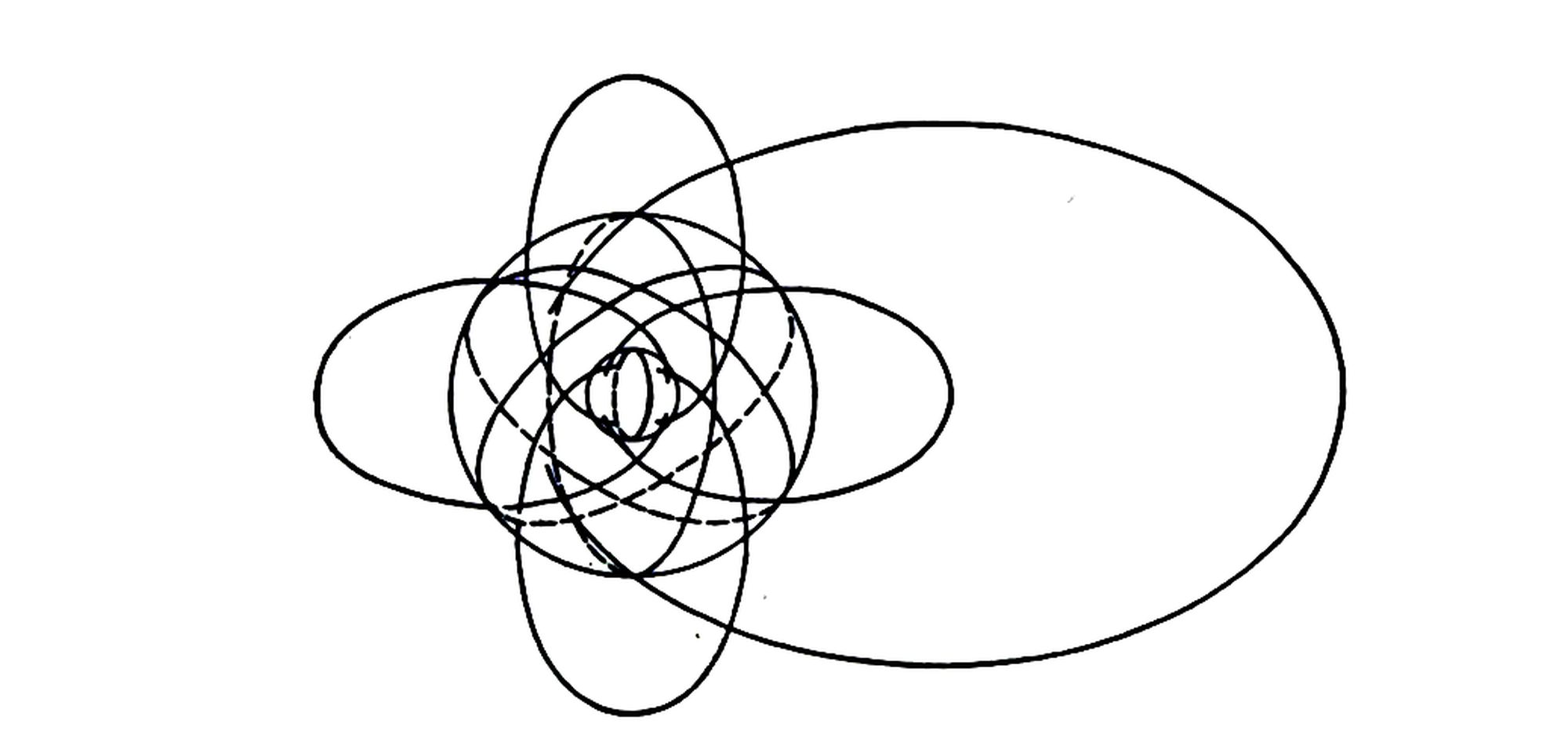

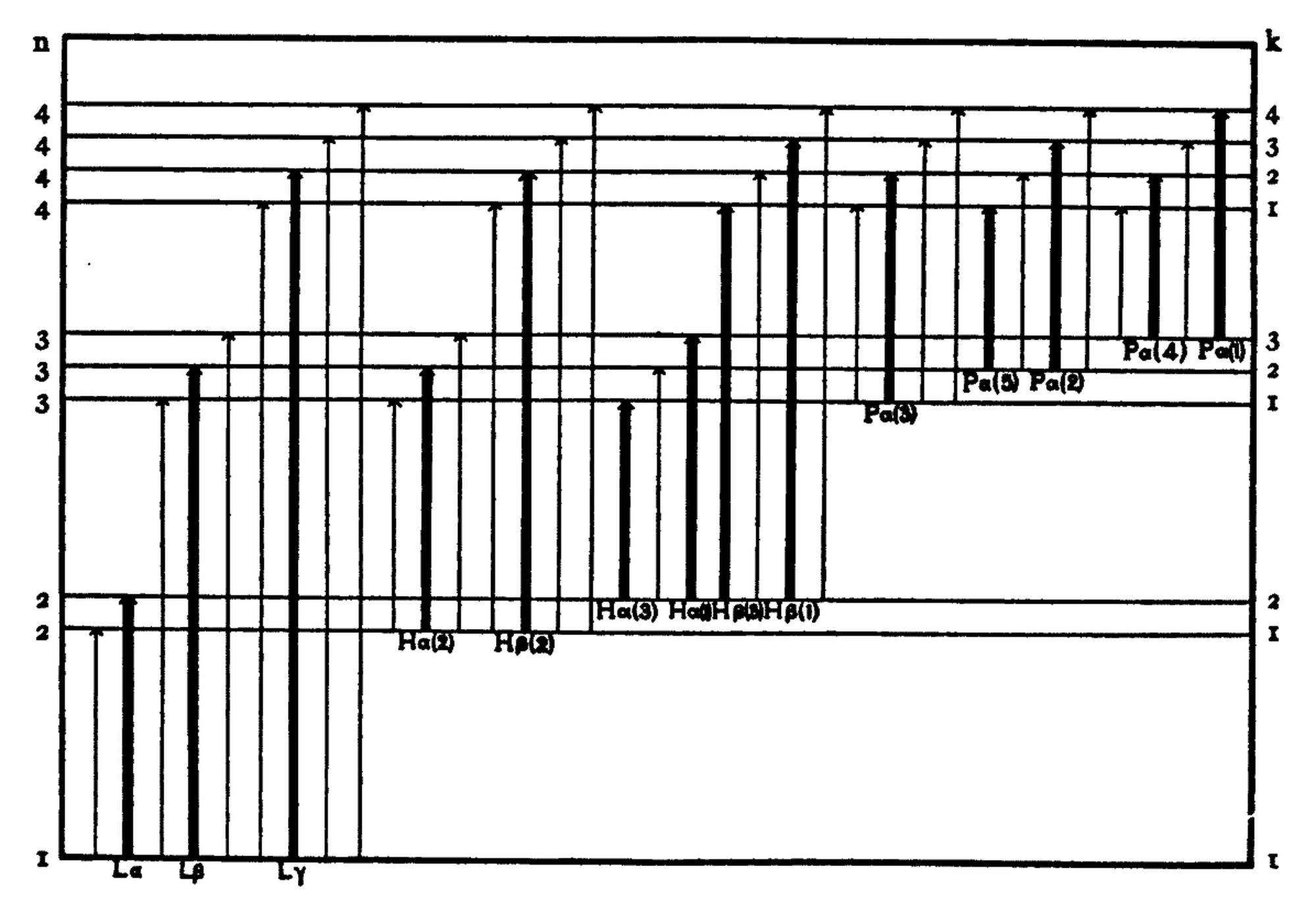

Figure 2

The hydrogen atom. The ten innermost orbits possible for the single electron of the atom of hydrogen are diagrammatically represented. All possible quantum transitions between the orbits are indicated as follows:—short dashes, Lyman series, terminating at a 1-quantum orbit; full lines, Balmer series, terminating at a 2-quantum orbit; long dashes, Paschen series, terminating at a 3-quantum orbit. Transfers are only possible between orbits with azimuthal quantum numbers differing by ±1.

When the energy supply from the environment is great enough,

the “outermost” (or most easily detachable) valency electron is

entirely removed by the energy absorbed. In consequence the atom is

superficially transformed, giving rise to a totally new spectrum,

which strongly resembles the spectrum of the atom next preceding in

the periodic system. Bohr’s table embodies the interpretation of

[Pg 13]

this resemblance—the so-called Displacement Rule of Kossell and

Sommerfeld[7]—which has recently been strikingly confirmed by a very

complete investigation of the arc and spark (neutral and ionized)

spectra of the atoms in the first long period.[8] It may be seen at

once, for instance, that the removal of the outermost (or )

electron from the atom of aluminum (

) produces an arrangement

of external electrons identical with that for magnesium (

). The

ionized atom produced by the complete removal of one electron gives,

like the neutral atom, two kinds of line spectrum—the ultimate lines

and the subordinate lines.

[Pg 14]

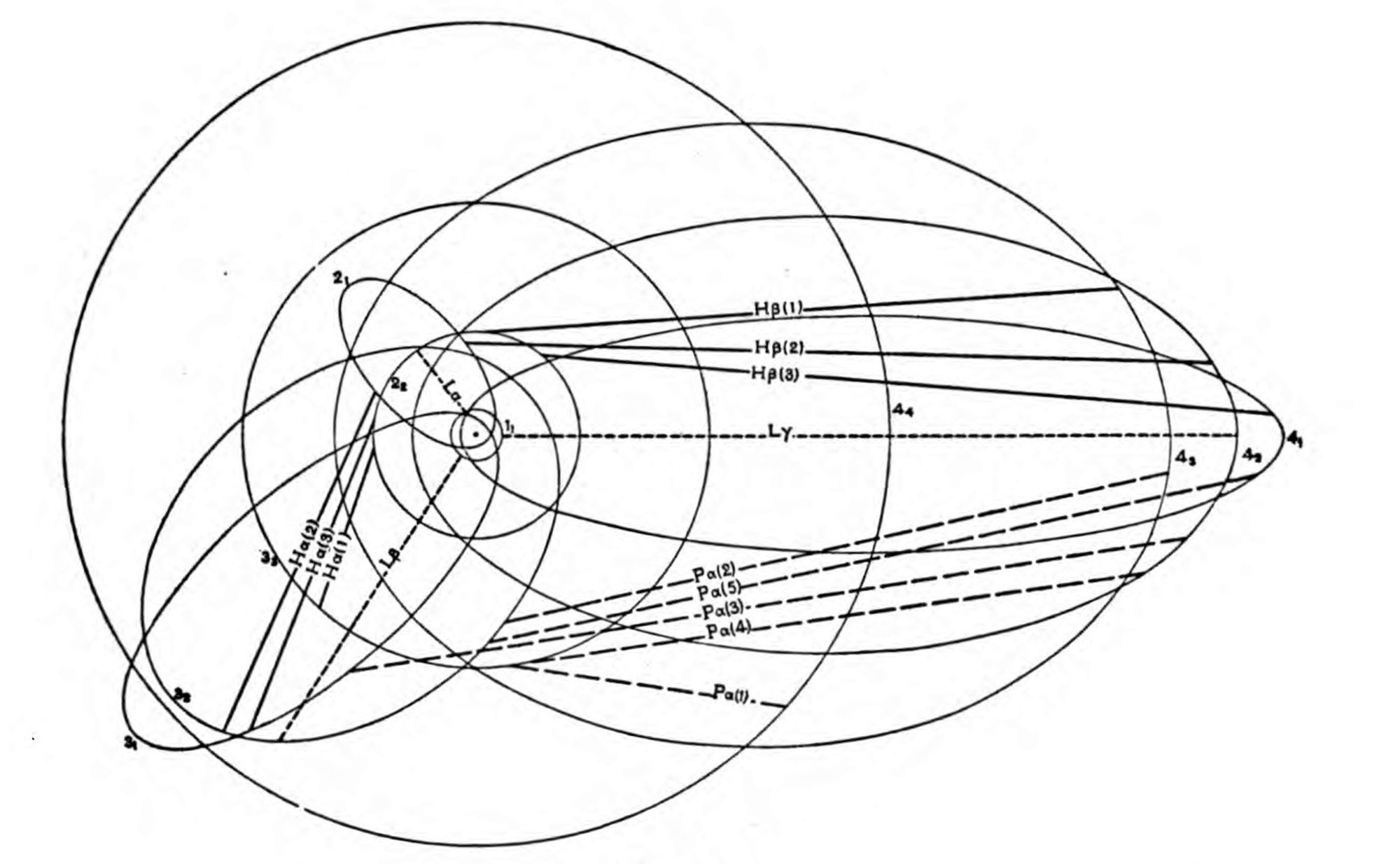

Figure 3

Energy levels for the hydrogen atom. Horizontal lines represent diagrammatically the levels of energy corresponding to all the possible electron orbits up to and including those of total quantum number four. Total quantum numbers are indicated on the left margin, azimuthal quantum numbers on the right margin. Transitions are only possible between orbits which differ by ±1 in azimuthal quantum number. All such possible transitions are indicated in the diagram by heavy lines. “Forbidden jumps,” for which the difference in azimuthal quantum number is zero or greater than 1, are indicated by light lines. This diagram embodies the same relations as Figure 2, the levels representing the various orbits in that figure.

Effectively, the ionized atom may be regarded as a new atom altogether.

It reproduces the spectrum of the atom of preceding atomic number,

in cases which have been fully investigated, with great fidelity,

excepting that the Rydberg constant in the series formula is multiplied

by four. For the twice and thrice ionized atoms the same is true, the

Rydberg constant being multiplied by nine and by sixteen in the two

cases. It is scarcely necessary to mention the beautiful confirmation

of the theory that has been furnished by the analyses[9][10] of the

spectra of Na, Mg, and Mg+, Al, Al+, and Al++, and Si, Si+, Si++,

and Si+++. The attribution of the Pickering series (first observed

in the spectrum of Puppis) to ionized helium was the first

established example of the displacement rule, and constituted one

of the earliest triumphs of the Bohr theory.[11] The detection and

resolution of the alternate components of that series, which fall very

near to the Balmer lines of hydrogen in the spectra of the hottest

stars, and the consequent derivation of the Rydberg constant for

helium,[12] represents an astrophysical contribution to pure physics

which is of the highest importance.

IONIZATION AND EXCITATION

The ionization potential of an atom is the energy in volts that is required in order to remove the outermost electron to infinity. The excitation potential corresponding to any particular spectral series is the energy in volts that must be imparted to the atom in the normal state in order that there may be an electron in a suitable electron orbit for the absorption or emission of that series. Several different excitation potentials are usually associated with one atom. The ionization potential and the excitation potentials are collectively termed the critical potentials.

From the astrophysical point of view, ionization and excitation [Pg 15] potentials are important as forming the basic data for the Saha theory of thermal ionization, with which the greater part of this work is concerned. A list of the ionization potentials hitherto determined is therefore reproduced in the following table. The first two columns contain the values obtained by the physical and spectroscopic methods, respectively. The third column contains “astrophysical estimates,” which are inserted here to make the table more complete. The derivation of the astrophysical values will be discussed[13] in Chapter XI. Physical values result from the direct application of electrical potentials to the element in question, and spectroscopic values are derived from the values of the optical terms. (See Appendix.)

| Atomic Number |

Element | Ionization potential | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Spectroscopic | Astrophysical | |||

| 1 | H | 14.4, 13.3 | 13.54 | 1, 2, 3 | |

| 2 | He | 25.4 | 24.47 | 5, 4 | |

| He+ | 54.3 | 54.18 | 3, 5 | ||

| 3 | Li | 5.37 | 3 | ||

| Li+ | 40 | 6 | |||

| 4 | Be | 9.6 | 7 | ||

| 5 | B | 8.3 | 7 | ||

| B+ | 19.0 | 7 | |||

| 6 | C+ | 24.3 | 8 | ||

| C++ | 45 | 9, 12 | |||

| 7 | N | 16.9 | 10 | ||

| N+ | 24 | 9, 12 | |||

| N++ | 45 | 9, 12 | |||

| 8 | O | 15.5 | 13.56 | 3, 11 | |

| O+ | 32 | 9, 12 | |||

| O++ | 50 | 45 | 12 | ||

| 10 | Ne | 16.7 | 13 | ||

| 11 | Na | 5.13 | 5.12 | 14, 3 | |

| Na+ | 30-35 | 15 | |||

| 12 | Mg | 7.75 | 7.61 | 16, 3 | |

| Mg+ | 14.97 | 3 | |||

| 13 | Al | 5.96 | 3 | ||

| Al+ | 18.18 | 17 | |||

| Al++ | 28.32 | 17 | |||

| 14 | Si | 10.6 | 8.5 | 18, 19 | |

| Si+ | 16.27 | 18 | |||

| Si++ | 31.66 | 18 | |||

| Si+++ | 44.95 | 8.5 | 18 | ||

| 15 | P | 13.3, 10.3 | 20, 21 | ||

| P++ | 29.8 | 7 | |||

| P+++ | 45.3 | 7 | |||

| 16 | S | 12.2 | 10.31 | 20, 12 | |

| S+ | 20 | 9, 12 | |||

| S++ | 32 | 9, 12 | |||

| S+++ | 46.8 | 7 | |||

| 17 | Cl | 8.2 | 13 | ||

| 18 | A | 15.1 | 22 | ||

| A+ | 33, 34, 41.5 | 23, 22, 24 | |||

| 19 | K | 4.1 | 4.32 | 14, 3 | |

| K+ | 20-23 | 14 | |||

| 20 | Ca | 6.09 | 3 | ||

| Ca+ | 11.82 | 3 | |||

| 21 | Sc | 6-9 | 25 | ||

| Sc+ | 12.5 | 19 | |||

| 22 | Ti | 6.5 | 26 | ||

| Ti+ | 12.5 | 19 | |||

| 23 | V | 6-9 | 25 | ||

| 24 | Cr | 6.7 | 3 | ||

| 25 | Mn | 7.41 | 35 | ||

| 26 | Fe | 5.9, 8.15 | 7.5 | 28, 29, 19 | |

| Fe | 13 | 19 | |||

| 27 | Co | 6-9 | 25 | ||

| 28 | Ni | 6-9 | 25 | ||

| 29 | Cu | 7.69 | 3 | ||

| 30 | Zn | 9.35 | 3 | ||

| Zn+ | 19.59 | 7 | |||

| 31 | Ga | 5.97 | 3 | ||

| 33 | As | 11.5 | 30 | ||

| 34 | Se | 12-13, 11.7 | 31, 32 | ||

| 35 | Br | 1.00 | 13 | ||

| 36 | Kr | 14.5 | 33 | ||

| 37 | Rb | 4.1 | 4.16 | 34, 3 [Pg 16] | |

| 38 | Sr | 5.67 | 3 | ||

| Sr+ | 10.98 | 3 | |||

| 42 | Mo | 7.1, 7.35 | 35, 36 | ||

| 47 | Ag | 7.54 | 3 | ||

| 48 | Cd | 8.95 | 3 | ||

| Cd+ | 18.48 | 7 | |||

| 49 | In | 5.75 | 37 | ||

| 51 | Sb | 8.5 ± 1.0 | 26 | ||

| 53 | I | 10.1, 8.0 | 38, 39 | ||

| 56 | Ba | 5.19 | 3 | ||

| Ba+ | 9.96 | 3 | |||

| 80 | Hg | 10.4 | 40 | ||

| 81 | Tl | 6.94 | 41 | ||

| 82 | Pb | 7.93 | 7.38 | 42 | |

| 83 | Bi | 8.0 | 30 | ||

| Bi+ | 14.0 | 30 [Pg 17] | |||

1 Horton and Davies, Proc. Roy. Soc., 97A, 1, 1920.

2 Mohler and Foote, J. Op. Soc. Am., 4, 49, 1920.

3 A. Fowler, Report on Series in Line Spectra, 1922.

4 Lyman, Phys. Rev., 21, 202, 1923.

5 Horton and Davies, Proc. Roy. Soc., 95A, 408, 1919.

6 Mohler, Science, 58, 468, 1923.

7 D. R. Hartree, unpub.

8 A. Fowler, Proc. Roy. Soc., 105A, 299, 1924.

9 Payne, H. C. 256, 1924.

10 Brandt, Zeit. f. Phys., 8, 32, 1921.

11 Hopfield, Nature, 112, 437, 1923.

12 R. H. Fowler and Milne, M. N. R. A. S., 84, 499, 1924.

13 Horton and Davies, Proc. Roy. Soc., 98A, 121, 1920.

14 Tate and Foote, Phil. Mag., 36, 64, 1918.

15 Foote, Meggers, and Mohler, Ap. J., 55, 145, 1922.

16 Foote and Mohler, Phil. Mag., 37, 33, 1919.

17 Paschen, An. d. Phys., 71, 151 and 537, 1923.

18 A. Fowler, Bakerian Lecture, 1924.

19 Menzel, H. C. 258, 1924.

20 Mohler and Foote, Phys. Rev., 15, 321, 1920.

21 Duffendack and Huthsteiner, Amer. Phys. Soc., 1924.

22 Horton and Davies, Proc. Roy. Soc., 102A, 131, 1922.

23 Shaver, Trans. Roy. Soc. Can., 16, 135, 1922.

24 Smyth and Compton, Amer. Phys. Soc., 1925.

25 Russell, Ap. J., 55, 119, 1922.

26 Kiess and Kiess, J. Op. Soc. Am., 8, 609, 1924.

27 Catalan, Phil. Trans., 223A, 1922.

28 Sommerfeld, Physica, 4, 115, 1924.

29 Gieseler and Grotrian, Zeit. f. Phys., 25, 165, 1924.

30 Ruark, Mohler, Foote, and Chenault, Nature, 112, 831, 1923.

31 Foote and Mohler, The Origin of Spectra, 67, 1922.

32 Udden, Phys. Rev., 18, 385, 1921.

33 Sponer, Zeit. f. Phys., 18, 249, 1923.

34 Foote, Rognley and Mohler, Phys. Rev., 13, 61, 1919.

35 Catalan, C. R., 176, 1063, 1923.

36 Kiess, Bur. Stan. Sci. Pap. 474, 113, 1923.

37 McLennan, Br. A. Rep., 25, 1923.

38 Foote and Mohler, The Origin of Spectra, 67, 1922.

39 Smyth and Compton, Phys. Rev., 16, 502, 1920.

40 Eldridge, Phys. Rev., 20, 456, 1922.

41 Mohler and Ruark, J. Op. Soc. Am., 7, 819, 1923.

42 Grotrian, Zeit. f. Phys., 18, 169, 1923.

[Pg 18]

By the use of one or other of the available methods, the data for neutral atoms are complete as far as atomic number 38, with the exception of carbon (6), fluorine (9) and germanium (32). The data for ionized atoms are also increasing, at the present time, in a very gratifying manner. The “hot spark” investigations of Millikan and Bowen,[14] which permit the estimation of the fifth and sixth ionization potentials of certain light atoms, are not included in the table. Under the conditions hitherto investigated in the stellar atmosphere, ionization corresponding to a potential of about fifty volts is the highest encountered, and accordingly ionization potentials that greatly exceed this value have no place in the present tabulation of astrophysically useful data. A knowledge of the higher critical potentials[15] is, however, of great interest in connection with the theoretical problems of the far interior of the star.

There are conspicuous gaps in the table, and it is to be feared that many of them are likely to remain unfilled. The spectra of the neutral atoms of carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen have hitherto defied analysis, and our knowledge of the corresponding ionization potentials must therefore depend on physical methods. For carbon, silicon, and similar refractory materials, such methods are difficult of application; the same applies to the metals. It is therefore probable that the ionization potentials of the neutral atoms of several of the lighter elements, of the platinum metals, and of the rare earths, will remain unknown or uncertain for some time to come. None of the atoms thus omitted is of immediate astrophysical importance.

As shown in the table, the values for the ionized and doubly ionized light atoms O+, O++, C++, N++, S+, and S++ are deduced only astrophysically. It may be hoped that the spectra of these atoms will soon be arranged in series, so that an accurate value of the ionization potential may be available, in place of the approximate one deduced from the stellar evidence, for the corresponding absorption lines are of importance in the spectra of the hotter stars.

[Pg 19]

The spectroscopic ionization potentials have an advantage over the

physical values, in that the corresponding state of the atom is

known with certainty, whereas physical methods can in general only

detect some critical potential, without assigning it definitely

to a particular transition. For example, it seems likely that in some

cases the first ionization, whether caused by incident radiation or

by electron impacts, corresponds to the loss of an electron by the

molecule:

where

represents the atom, and

the electron. The effect of

increased excitation would then be the decomposition

The first reaction would produce the ionized molecule, and the second

would produce the ionized and neutral atoms simultaneously. It

might thus happen that the

spectrum could appear without the

previous appearance of the

spectrum, since all of the element was

present in the form

before ionization.

The above is only a simple illustrative example of the possible complexity in the physical determination of ionization potentials. The interpretation of four successive critical potentials for hydrogen has been discussed by Franck, Knipping and Krüger,[16] while eight have been detected by Horton and Davies[17] for the same element. Similarly Smyth[18] discusses four critical voltages for nitrogen. No explicit attempt has yet been made to use these facts for the interpretation of astrophysical data, but they may account for the unexplained absence of some neutral elements from the cooler stars. The absence is generally to be attributed, as will be shown in Chapter V, to the non-occurrence of suitable lines in the part of the spectrum usually examined. But [Pg 20] it is possible that the persistence of the molecule has a definite significance in the case of nitrogen, where the ionization potential is as high as 16.9 volts.

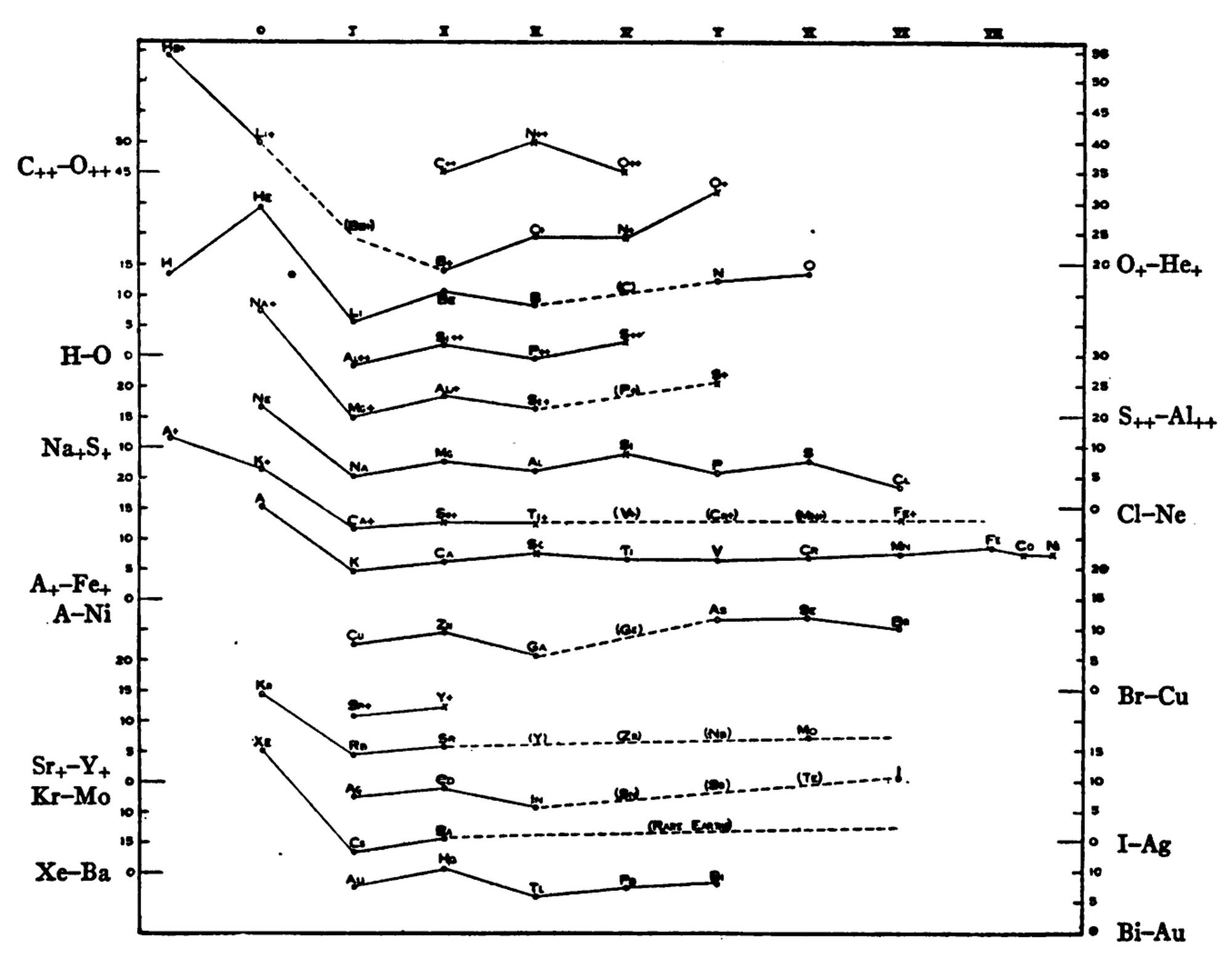

Figure 4

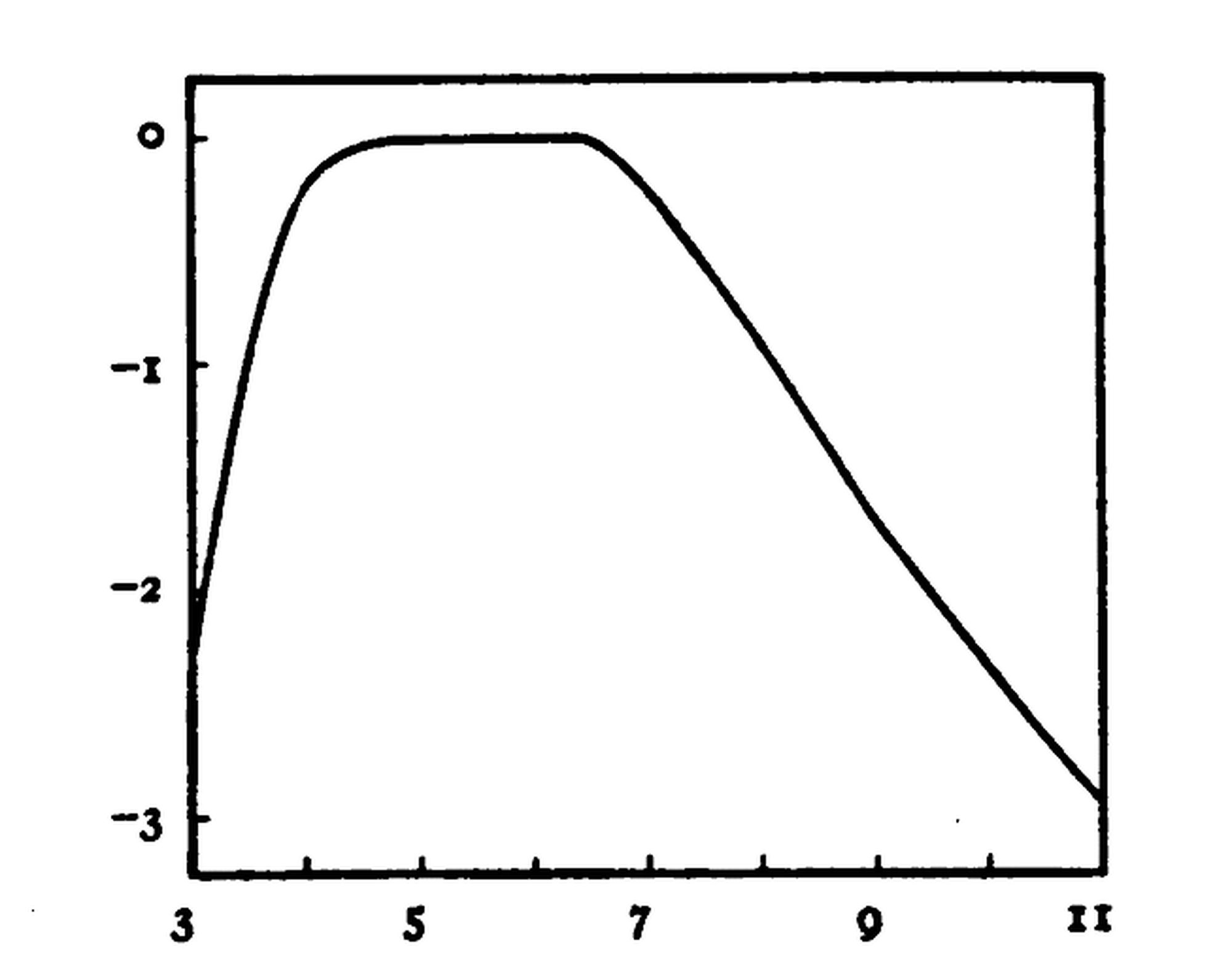

Relation between ionization potential and position in the periodic system. Ordinates are ionization potentials in volts, on the equal but shifted scales indicated alternately on left and right margins. Abscissae are columns of the periodic table. Physical determinations of ionization potential are indicated by open circles; dots give spectroscopic determinations, and crosses denote astrophysical estimates. Conjectural portions of the curve are indicated by broken lines, and atoms of unknown ionization potential are enclosed in parentheses.

The increasing completeness of the table of ionization potentials suggests a re-examination of the relation recently traced by the writer[19] between ionization potential and atomic number. The original diagram, in which columns of the periodic table are treated as abscissae, and the ordinates are ionization potentials on equal but shifted scales, so that analogous elements fall one below another, is here reproduced, with the addition of data more recently obtained.

[Pg 21]

The Displacement Rule of Kossell and Sommerfeld leads us to expect a pronounced similarity between the line drawn in the diagram from the point representing one element to that representing the next, and the corresponding line for the ionized atoms of the same elements, the latter being shifted one place to the left for each electron removed. The points for once and twice ionized atoms are inserted into the diagram on this principle, and the parallelism is found to exist. The regularities of the diagram and their possible significance (such, for example, as the pairing of the valency electrons, the second being harder to remove than the first) were discussed in the original paper. All the more recent data appear to confirm the conclusion there set forth, that the relation between ionization potential and atomic number is very closely the same in each period.

DURATION OF ATOMIC STATES

In addition to the critical potentials, which give a measure of the ease with which an atom is excited or ionized, astrophysical theory requires an estimate of the readiness with which an atom recovers after excitation or ionization. It appears probable that this factor, like the critical potentials, is independent of external conditions, and depends upon something that is intrinsic in the atomic structure. The “life” of the atom has been extensively investigated in the laboratory, and has been shown to be a small fraction of a second in duration. Probably this subject of “atomic lives” is still in an initial stage, and the accuracy of the results and the range of elements discussed will be greatly increased in the near future. A summary of the material obtained up to the present time is contained in the following table. Successive columns contain the atom discussed, the deduced atomic life in seconds, the authority, and the reference.

The data are practically confined to hydrogen and mercury, and for

both these elements the atomic life appears to be of the order

[Pg 22]

.

Astrophysical estimates of the life of the excited calcium atom

have been made by Milne,[20] who derives values of the order

. This is so near to the

values obtained in the laboratory that it seems permissible, in

the absence of further precise data, to assume an atomic life of

, as a working hypothesis,

for all atoms. The same value is unlikely to obtain for all atoms; in

particular it may be expected to differ for atoms in different states

of ionization. But here astrophysics must be entirely dependent on

further laboratory work for the determination of a quantity that is of

fundamental importance.

| Atom | Life | Authority | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wien | An. d. Phys., 60, 597, 1919 | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Dempster | Phys. Rev., 15, 138, 1920 | ||

| Wood | Proc. Roy. Soc., 99A, 362, 1921 | ||

| Franck and Grotian | Zeit. f. Phys., 4, 89, 1921 | ||

| Mie | An. d. Phys., 66, 237, 1921 | ||

| Wien | An. d. Phys., 66, 232, 1921 | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Ibid. | An. d. Phys., 73, 483, 1924 | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Ibid. | Ibid. | ||

| Turner | Phys. Rev., 23, 464, 1924 | ||

| Webb | Phys. Rev., 21, 464, 1923 |

RELATIVE PROBABILITIES OF ATOMIC STATES

The relative intensities of lines in a spectrum must depend fundamentally upon the relative tendencies of the atom to be in the corresponding states. To a subject which, like astrophysics, depends [Pg 23] for its data largely upon the relative intensities of spectral lines, the theory of the relative probabilities of atomic states is of extreme importance. The question is obviously destined to become an important branch of spectrum theory. It has been discussed, from various aspects, by Füchtbauer and Hoffmann,[21] Einstein,[22] Füchtbauer,[23] Kramers,[24] Coster,[25] Fermi,[26] and Sommerfeld.[27] The comparison with observation has been made, up to the present, only for a few elements. The relative intensities of the fine-structure components of the Balmer series of hydrogen were examined by Sommerfeld,[28] and exhaustive work with the calcium spectrum has recently been carried out by Dorgelo.[29] The astrophysical application of the data bearing on relative intensities of lines in the spectrum of one and the same atom, while an essential branch of the subject, is a refinement which belongs to the future rather than to the present.

EFFECT ON THE SPECTRUM OF CONDITIONS AT THE SOURCE

(a) Temperature Class.—It is found experimentally that the relative intensities of the lines in the spectrum of a substance are altered when the temperature is changed. Some lines, notably the ultimate lines mentioned in a previous paragraph, predominate at low temperature. Other lines, which are weak under these conditions, become stronger if the temperature is raised, and lines which are the characteristic feature of the spectrum at the highest temperatures that can be attained in the furnace are often imperceptible at the outset. The effects are more conspicuous, and have been most widely studied, in the spectra of the metals, which are rich in lines and are amenable to furnace conditions. The results of such experiments, which [Pg 24] are chiefly the work of A. S. King, are expressed by the assignment of a “temperature class,” ranging from I to V, to each line; Class I represents the lines characteristic of the lowest temperatures, and Class V denotes the lines that require the greatest stimulation.

The temperature class of a line is intimately connected with the amount of energy required to excite the line. It may, indeed, be used as a rough criterion of excitation potential, high temperature class indicating high excitation energy. The temperature class is therefore useful in assigning series relations to unclassified lines, and is of value to the astrophysicist chiefly in this capacity of a classification criterion. King’s work on silicon shows, for instance, that 3906 is of Class II, and is therefore not an ultimate line—a fact which has considerable significance in studying the astrophysical behavior of the line.

The correlation of temperature class with excitation potential receives an immediate explanation in terms of the theory of thermal ionization. It furnishes a useful laboratory corroboration of the theory by showing that the thermal excitation of successive lines, with rising excitation potential, takes place in qualitative agreement with prediction.

The appended list shows the atoms for which the spectra have been analyzed by King on the basis of temperature class:

| Element | Reference | Element | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | Mt. W. Contr. 66, 1912 | Calcium | Mt. W. Contr. 150, 1918 |

| Titanium | Mt. W. Contr. 76, 1914 | Strontium | Ibid. |

| Vanadium | Mt. W. Contr. 94, 1914 | Barium | Ibid. |

| Chromium | Ibid. | Magnesium | Ibid. |

| Cobalt | Mt. W. Contr. 108, 1915 | Manganese | Mt. W. Contr. 198, 1920 |

| Nickel | Ibid. | Silicon | Pub. A. S. P., 22, 106, 1921 |

(b) Pressure.—In the laboratory the observed effects of pressure[30] are a widening and shifting of the lines in the spectrum—effects which differ in magnitude and direction for different lines. The phenomena are well marked under pressures of several atmospheres.

[Pg 25]

Recent developments of astrophysics, such as are summarized in Chapter III and Chapter IX, have shown that the pressures in stellar atmospheres are normally of the order of a hundred dynes per square centimeter, or less. At such pressures no appreciable pressure shifts will occur, and indeed one of the most direct methods by which these exceedingly low pressures in reversing layers have been established[31] is based on the absence of appreciable pressure effects.

(c) Zeemann Effect.—The magnetic resolution of spectral lines into polarized components[32] has, as yet, for the astrophysicist, chiefly a value as a criterion for classifying spectra. In the field of solar physics proper, a direct study of the Zeemann effect has led to important results.[33] The present study is not, however, explicitly concerned with the sun, except in comparing solar features with similar features that can also be examined in the stars.

The investigations of Landé on term structure and Zeemann effect[34] for multiplets have shown how the Zeemann pattern formed by the components into which a line is magnetically resolved can be related to the series attribution of the line. This provides a method of classifying spectra which are rich in multiplets, and which have previously defied analysis. The indirect astrophysical value of the Zeemann effect is, therefore, very great.

(d) Stark Effect.—The effect of an electric field in resolving spectral lines into polarized components was first pointed out by Stark[35] for hydrogen and helium. Several other investigators have since studied the effect for these two elements,[36] and for [Pg 26] various metals.[37][38] Unlike the temperature and magnetic effects, the Stark effect has not been used as a criterion for the series relations of unclassified lines.

The Stark effect has not been detected in the solar spectrum, presumably because the concentration of free electrons prevents the formation of large electrostatic fields.

Several investigators, however, have contemplated in the Stark effect a possible factor influencing the stellar spectrum.[39][40] It does not seem unlikely that nuclear fields could operate as a sensible general electrostatic field at the photospheric level, thus producing a widening and winging of certain lines. The question has been numerically discussed by Hulburt,[41] and Russell and Stewart,[42] in an examination of Hulburt’s work, concluded that the Stark effect might possibly make some contribution (probably not a preponderant one) to the observed widths of lines in the solar spectrum. The question is not definitely settled, but it appears well to keep so important a possibility in mind.

[1] International Atomic Weights, 1917.

[2] Aston, Isotopes, 1922; Phil. Mag., 47, 385, 1924; Nature, 113, 192, 856, 1924; Ibid., 114, 273, 716, 1924. Products of radioactive disintegration are omitted.

[3] Clarke and Washington, Proc. N. Ac. Sci., 8, 108, 1922.

[4] Bohr, Naturwiss., 11, 619, 1923.

[5] Sommerfeld, Atombau und Spektrallinien, 3d. edition, 286, 1922.

[6] A. Fowler, Proc. Roy. Soc., 105A, 299, 1924.

[7] Sommerfeld, Atombau und Spektrallinien, 3d edition, 457, 1922.

[8] Meggers, Kiess, and Walters, J. Op. Soc. Am., 9, 355, 1924.

[9] A. Fowler, Report on Series in Line Spectra, 1922; Bakerian Lecture, 1924.

[10] Paschen, An. d. Phys., 71, 151, 1923.

[11] Sommerfeld, Atombau und Spektrallinien, 3d. edition, 255, 1922; A. Fowler, Proc. Roy. Soc., 90A, 426, 1913; Paschen, An. d. Phys., 50, 901, 1919.

[12] H. H. Plaskett, Pub. Dom. Ap. Obs., 1, 348, 1922.

[14] Millikan and Bowen, Phys. Rev., 23, 1, 1924; Nature, 114, 380, 1924.

[15] Hartree, Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc., 22, 464, 1924; Thomas, Phys. Rev., 25, 322, 1925.

[16] Verh. d. Deutsch. Phys. Ges., 21, 728, 1919.

[17] Phil. Mag., 46, 872, 1923.

[18] Proc. Roy. Soc., 103A, 121, 1923.

[19] Proc. N. Ac. Sci., 10, 322, 1924.

[20] Proc. Phys. Soc. Lond., 36, 94, 1924.

[21] An. d. Phys., 43, 96, 1914.

[22] Phys. Zeit., 18, 121, 1917.

[23] Phys. Zeit., 21, 322, 1922.

[24] Proc. Copenhagen Ac., 1919.

[25] Physica, 4, 337, 1924.

[26] Physica, 4, 340, 1924.

[27] Zeit. f. Tech. Phys., 5, 2, 1925.

[28] Atombau und Spektrallinien, 3d edition, 588, 1922.

[29] Physica, 3, 188, 1923; Zeit. f. Phys., 13, 206, 1923; ibid., 22, 270, 1924; Dissertation, Utrecht, 1924; Physica, 5, 27, 1925.

[30] King, Mt. W. Contr. 53, 1911; ibid., 60, 1912.

[31] St. John and Babcock, Ap. J., 60, 32, 1924.

[32] Zeemann, Researches in Magneto-Optics, 1911.

[33] Hale, Mt. W. Contr. 30, 1908.

[34] Landé, Zeit. f. Phys., 15, 189, 1923.

[35] Stark, Elektrische Spektralanalyse Chemischer Atome, 1914.

[36] Merton, Proc. Roy. Soc., 92A, 322, 1915; ibid., 95A, 33, 1919.

[37] Anderson, Mt. W. Contr. 134, 1917.

[38] Takamine, Mt. W. Contr. 169, 1919.

[39] Evershed, Observatory, 45, 166, 1922; ibid., 45, 296, 1922.

[40] Lindemann, Observatory, 45, 167, 1922.

[41] Hulburt, Ap. J., 59, 177, 1924.

[42] Russell and Stewart, Ap. J., 59, 197, 1924.

[Pg 27]

IT is well to distinguish the different meanings that are to be associated with the term “stellar temperature.” The observed energy distribution in the spectrum, combined with the theory of black-body radiation, lead to a quantity known as the “effective temperature” of the star. This is the temperature of a hypothetical black body, the spectrum of which would have the observed energy distribution of the star in question. It has often been emphasized that the effective temperature is merely a label, for it is not the actual temperature of any specific portion of the star. Presumably the temperature of a star falls off, from the center outwards, according to the laws expressed by the theory of radiative equilibrium, and though it might thus be possible to specify, on certain assumptions, the depth in a star at which the effective temperature coincides with the actual temperature, no observational significance could attach to the information.

The theory of radiative equilibrium[43] enables us to specify the temperature gradient, and in particular to determine the central temperature, the effective temperature, and the boundary temperature, corresponding to a given energy output. These three quantities are essentially arbitrary, and the second is the only one susceptible of direct measurement, while none of them represents the actual temperature of any assignable region. In order to clarify ideas it is useful to regard the effective temperature as representing roughly the temperature of the photosphere, that is, of the region in the star that gives rise to the approximately black continuous background of the spectrum. It must, however, be remembered that “the theory provides a definite relation between temperature and optical depth, involving only one constant, the effective temperature. Suppose now ... [Pg 28] we arbitrarily select a certain temperature, and name it the photospheric temperature, and name the unknown depth at which it occurs the photospheric depth; this depth will be described by some unknown transmission coefficient, to be determined. If, taking account of absorption and emission, we proceed to calculate the transmission coefficient ... we shall simply recover the optical depth predicted by Schwarzschild’s theory.” (Milne.)[44] No method of measuring the effective temperatures of the stars by comparing their energy spectrum with that of a black body can remove the arbitrariness of the quantity thus measured.

The theory of thermal ionization permits estimates to be made of the temperatures in the reversing layers of stars. These temperatures refer to the average level at which are situated the absorbing atoms corresponding to the lines used. The differences of effective level[45] for different atoms render these “ionization temperatures” difficult to define consistently, but they represent actual temperatures of assignable regions in the star, and the extent of their agreement with the temperatures derived from the distribution of energy in the continuous spectrum is a matter of extreme interest. The material and theory from which the ionization temperatures are derived is the subject matter of Chapters VI to IX. The temperature scale used in calibration and in the discussion of the theory of thermal ionization is the scale derived from the measured effective temperatures.

The derivation of a definitive scale of effective temperatures from the numerous available observations is probably impossible at the present time. The methods employed differ widely, and the conditions for accurate intercomparison cannot be regarded as fully established. The material at present available, however, permits some general conclusions, and as the needs of astrophysics demand a working temperature scale, such conclusions are summarized in the present chapter.

[Pg 29]

In the discussion of the material a difficulty immediately arises. The scale to be derived must be based entirely, in the present stage of the observations, upon the apparently brighter stars, and it is notorious that they are not homogeneous in absolute magnitude. Theory predicts[46] that absolutely bright stars will have a lower effective temperature than stars of low luminosity belonging to the same spectral class, and this prediction is, on the whole, verified by observation. The material must therefore be selected on the basis of luminosity if a standard temperature scale is to be formed, and probably the temperature scale to be aimed at should refer to stars of some one absolute magnitude adopted as standard. Theoretically, standard mass might be preferable to standard luminosity, but, in the present state of the subject, so few masses are known that such a system would not be practicable. The ideal of referring to standard absolute magnitude was not attained by the earlier temperature scales, which were apparently based upon averages for all the available brighter stars.

The more comprehensive data for the study of the stellar temperature scale are the spectrophotometric measures of Wilsing and Scheiner,[47] of Wilsing,[48] of E. S. King,[49] and of Rosenberg.[50] The temperature scales derived by Wilsing and by Rosenberg differ by a linear factor; Rosenberg assigns higher temperatures to the hotter stars, and lower temperatures to the cooler stars. These temperature scales, and their intercomparison, have been very fully discussed by Brill,[51] who reduces all the measures to the scale given by Wilsing, and gives, for the principal Draper classes, the following comparative table for the corrected mean effective temperatures on the absolute centigrade scale.

In addition to the comprehensive data just quoted, there have been [Pg 30] numerous determinations of the temperatures of individual bright stars, chiefly by Abbot,[52] Coblentz,[53] Sampson,[54] and H. H. Plaskett.[55] In the main these values confirm the scale given in Table V, but sometimes considerable differences occur in the values given for individual stars by different investigators. At the same time, each observer is usually reasonably self-consistent, and the deviations must therefore be ascribed to differences of method. Some of the results are reproduced, for illustration, in Table VI.

| Class | Wilsing | Rosenberg | E.S. King Color Temperature |

E.S. King Total Radiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12300° | 30000° | 22700° | 22700° | |

| 11450 | 18000 | 15200 | 14900 | |

| 10250 | 1200 | 11600 | 11300 | |

| 9000 | 9000 | 8800 | 8600 | |

| 7950 | 7850 | 7900 | 7700 | |

| 6880 | 6930 | 7000 | 6800 | |

| 5980 | 6000 | 6040 | 5870 | |

| 5250 | 5200 | 5090 | 4950 | |

| 4570 | 4570 | 4570 | 4440 | |

| 3860 | 3840 | 3640 | 3550 | |

| 3550 | 3580 | 3430 | 3340 |

It is seen that the effective temperatures of individual hotter

stars vary widely among themselves. This is largely a result of the

difficulty of making the appropriate correction for atmospheric

extinction. It must, then, be supposed that the temperatures derived by

spectrophotometric methods are not trustworthy for stars hotter than

Class . The values determined by the earlier observers for the

and

classes are almost certainly too low. Rosenberg’s value

of 30,000° for

is, however, most probably too high, as will be

inferred later from the ionization temperature scale.

For the cooler stars small discrepancies also occur among the different observers. In the writer’s opinion, the lowest estimates for the [Pg 31] temperatures of the cooler stars are probably nearest to the truth.

| Star | Abott Radiometric |

Coblentz Thermoelectric |

Plaskett Wedge Method |

Sampson Photoelectric |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ori( |

13000° | 25000° | |||

| Cas( |

15000° | 30000 | |||

| Per( |

15000 | 14000 | |||

| Ori( |

16000° | 10000 | 14800 | ||

| Lyr( |

14000 | 8000 | 11600 | ||

| 11000 | 12800 | ||||

| ( |

Cyg( |

9000 | 9000 | 10900 | |

| Aql( |

8000 | ||||

| Cas( |

9000 | 10700 | |||

| 6000 | 8300 | ||||

| Aur( |

5800 | 6000 | 5500-6000 | 5500 * | |

| 4000 | 4200 | ||||

| Gem( |

5500 | 5000-5500 | 4200 | ||

| Tau( |

3000 | 3500 | 3400 | ||

| Ori( |

2600 | 3000 | 3400 | ||

| Peg( |

2850 | 3200 | |||

* Temperature assumed in calibration of scale.

It was mentioned at the outset that dwarf stars appear to be at a higher temperature than giants of the same spectral class. The following table summarizes the differences in temperature, as compiled by Seares.[56]

| Class | Effective Temperature | |

|---|---|---|

| Giant | Dwarf | |

| 6080° | 6080° | |

| 5300 | 5770 | |

| 4610 | 5500 | |

| 3860 | 4880 | |

| 3270 | 4120 | |

| 3080 | 3330 | |

[Pg 32]

A more detailed list of giant and dwarf temperatures was compiled

in 1922 by Hertzsprung[57] from all the material then available.

The tabulation that follows contains his values for

(the “reciprocal temperature,” where

is 14,600), and the

corresponding absolute temperature, in degrees centigrade.

| Mt. W. Class | Temperature Giant |

Temperature Dwarf |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.00 | 7300° | |||

| 2.16 | 6770 | |||

| 2.08 | 6990 | |||

| 2.26 | 6460 | |||

| 2.30 | 6350 | |||

| 2.11 | 6920 | |||

| 2.30 | 6350 | |||

| 2.29 | 6370 | |||

| 2.34 | 6240 | |||

| 2.36 | 6190 | |||

| 2.48 | 5880 | |||

| 2.30 | 2.51 | 6340° | 5810 | |

| 2.45 | 5970 | |||

| 2.71 | 5100 | |||

| 2.83 | 2.62 | 5170 | 5580 | |

| 2.92 | 2.68 | 5020 | 5440 | |

| 2.92 | 2.64 | 5020 | 5530 | |

| 3.15 | 4730 | |||

| 3.09 | 4820 | |||

| 3.15 | 4730 | |||

| 3.25 | 2.76 | 4480 | 5300 | |

| 3.20 | 4560 | |||

| 3.29 | 4430 | |||

| 3.39 | 3.03 | 4300 | 4840 | |

| 3.48 | 3.11 | 4180 | 4700 | |

| 3.50 | 3.05 | 4160 | 4790 | |

| 3.54 | 4130 | |||

| 3.83 | 3810 | |||

| 3.86 | 3870 | |||

| 4.14 | 3530 | |||

| 4.33 | 3370 | |||

| 4.36 | 3350 | |||

| 4.35 | 3360 | |||

| 4.49 | 3250 | |||

| 4.45 | 3280 | |||

| 3.93 | 3720 |

[Pg 33]

The difference in temperature between giant and dwarf stars of the same spectral class is clearly shown in the foregoing tables. The relation of absolute magnitude to effective temperature within a given class must be regarded as definitely established by observation.

The temperatures for the cooler giant stars in both these lists are

somewhat lower than those given for the corresponding classes in Table V.

The temperature of , for instance, is placed nearer to 4000°

than to 4500°. The fact that the sun, a typical

dwarf, has an

effective temperature of 5600° seems to favor these lower values.

| Class | Temperature | Class | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3000° | 9000° | ||

| 3000 | 10000 | ||

| 3500 | 13500 | ||

| 4000 | 15000 | ||

| 5000 | 17000 | ||

| 5600 | 18000 | ||

| 7000 | 20000 | ||

| 7500 | 25000 | ||

| 8400 | 35000 |

In concluding the summary of stellar temperatures, the ionization temperature scale is given in the foregoing table. The discussion on which the table is based is contained in Chapters VI to IX, and it is merely placed here for comparison with the preceding tabulations.

[43] Eddington, Zeit. f. Phys., 7, 351, 1921.

[44] Phil. Trans., 223A, 201, 1922.

[47] Wilsing and Scheiner, Pots. Pub., 24, No. 74, 1919.

[48] Pots. Pub., 24, No. 76, 1920.

[49] H. A., 76, 107, 1916.

[50] A.N., 193, 356, 1912.

[51] A. N., 218, 210, 1923; ibid., 219, 22 and 354, 1923; Die Strahlung der Sterne, Berlin, 1924.

[52] Rep., Smithsonian Ap. Obs., 1924.

[53] Pop. Ast., 21, 105, 1923.

[54] M. N. R. A. S., 85, 212, 1925.

[55] Pub. Dom. Ap. Obs., 2, 12, 1923.

[56] Ap. J., 55, 202, 1922.

[57] Lei. An., 14, 1, 1922.

[Pg 34]

THE theory of thermal ionization enables us to make an analysis of the spectrum of the stellar reversing layer by predicting the number of atoms of any given kind that will be effective in absorbing light from the interior of the star, under given conditions, and by comparing the predicted values with the observed intensities of the corresponding absorption lines. The results depend partly on definite physical constants associated with the atoms—the ionization and excitation potentials, and the arrangement of the electrons around the nucleus. The temperature and pressure of the region in which the atom is situated are also required before the theory can be applied. The scale of stellar temperatures was discussed in the preceding chapter, and the present chapter is devoted to a synopsis of the modern views as to pressures in the reversing layer.

Strictly speaking, we cannot refer to “the pressure in the reversing layer,” for, like the temperature, the pressure has a gradient throughout the star. This gradient, as derived from the theory of radiative equilibrium,[58] is steep in the far interior of the star, but towards the outside the rapid fall of pressure begins to decrease, and changes somewhat abruptly to a very small gradient in the photospheric region, where radiation pressure and gravitation are of the same order of magnitude. Outside this layer of transition between the region dominated by radiation pressure and the region dominated by gravitation, the pressure gradient is very shallow, and decreases until, in the tenuous outer regions of the star, there is no appreciable pressure gradient, and atoms are practically floating freely.

[Pg 35]

The outermost regions of the atmosphere, at these exceedingly low pressures, make little or no contribution to the ordinary stellar spectrum; they can only be studied in the high-level chromosphere by means of the flash spectrum obtained at a total eclipse of the sun. The spectra that are ordinarily examined are from a region that is at an appreciable depth within the star—the depth from which the light of each individual wave-length can penetrate. The “layer” of which we can obtain a spectrum is therefore not at the same depth for all frequencies; it is most deep-seated in regions of continuous background, and nearest to the surface of the star at the centers of strong absorption lines. The pressures from which the different parts of the spectrum originate differ in the same way, and the idea of “pressure in the reversing layer” is not an easy one to define significantly.

For theoretical purposes it is usual to deal with the pressure at

a given “optical depth” (a measure of the amount of absorbing

matter traversed by the radiation in coming from the level

considered). The optical depth is connected with the density

, the mass coefficient of absorption for unit density,

,

and the vertical depth,

, in the star, by the relation[59]

The density gradient is thus eliminated. The optical depth is

furthermore related to the pressure

by the relations

where

is the value of gravity at the point in question, and

whence

In considering the stellar atmosphere we are dealing with a layer

so near the surface that the value of g involved is effectively the

“surface gravity” for the star. If is constant, a condition

[Pg 36]

probably approximately fulfilled,[60] the pressure at constant optical

depth is then directly proportional to the surface gravity, which

varies as the product of the mean density and the radius of the star.

Some idea of the range in pressure with which we shall be concerned in

the stellar atmosphere can therefore be obtained from stars of known

mean density and radius.

The data for eight such stars, all of the second type, are contained in Table X, which is adapted from tabulations given by Shapley.[61] Successive columns contain the name of the star, the spectral class, the mean densities of the two components in terms of the solar density, the hypothetical radii of the two components (on the assumption of solar mass) in terms of the sun’s radius, and the product of mean density and radius for each component.

| Star | Class | Mean density | Radius | Product | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SX | Cas | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | 15.3 | 18.6 | 0.006 | 0.004 | |

| RX | Cas | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 0.007 | 0.006 | |

| RZ | Oph | 0.001 | 0.00003 | 10.1 | 33.5 | 0.010 | 0.001 | |

| RT | Lac | 0.0013 | 0.010 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.059 | 0.046 | |

| W | Cru | 0.00002 | 0.000025 | 94 | 36 | 0.00019 | 0.0009 | |

| U | Peg | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | |

| W | G | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.6 | |

| Sun | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

In mean density these stars display a range of , while the

range in surface gravity is

, illustrating the significant fact

that the mean density varies far more widely than the surface gravity.

The latter quantity is the important one in determining the pressure

that may be assumed to exist in the reversing layer. If the masses of

the very luminous stars of low mean density, such as W Crucis, exceed

the solar mass, as they most probably do, the hypothetical radii are

[Pg 37]

increased, and the range in surface gravity becomes even smaller than

before.

The data for stars of known mean density and radius permit the

estimation of the range in surface gravity, and hence of the range

in pressure, encountered in the reversing layer. In the absence of

knowledge of the appropriate optical depth, however, the actual

pressure cannot be deduced from such considerations, and recourse

must be made to more indirect methods. The present view is based upon

a number of considerations, none of which would alone be of great

weight. All of the conclusions, taken together, however, indicate

that the upper limit of the pressure for the region in which the

Fraunhofer lines originate is of the order of

.

Attention was first called to the probability of an extremely low pressure in the reversing layer by R. H. Fowler and Milne,[62] in advancing the form of ionization theory which is to be analyzed in later chapters. The conclusion that the pressure in the reversing layer is exceedingly low was a direct outcome of their discussion, and they mentioned that the results from other methods converged in the same direction.

Russell and Stewart,[63] in a specific discussion of the pressures

at the surface of the sun, have established beyond question, and on

quite other grounds, that the pressure for the solar reversing layer

is indeed of the order suggested by Fowler and Milne. The value

need then no longer be

regarded as a result of the Fowler-Milne theory, and may be used

without redundancy in deriving a stellar temperature scale from that

theory.

METHODS OF ESTIMATING REVERSING LAYER PRESSURES

Russell and Stewart examined the evidence for reversing layer pressures derived from the following sources: (a) Shifts of spectral lines due to pressure, (b) Sharpness of lines, (c) Widths of lines, (d) Flash spectrum, (e) Equilibrium of outer layers, (g) Ionization and chemical equilibrium in the solar [Pg 38] atmosphere. In addition to these we have (f) the observed limit of the Balmer series in the hotter stars, where the hydrogen lines are at or near their maximum. These sources of evidence will now be briefly discussed.

(a) Shifts of Spectral Lines.—It was at one time supposed that displacements of spectral lines, corresponding to pressures of several atmospheres, could be found in stellar spectra. More recent work,[64] however, has shown conclusively that the pressure shifts that occur are so small that it is impossible to estimate a pressure from them with any approach to accuracy. The estimated pressures are of the same order as their probable errors. This being so, the most that can be expected of the method based upon pressure effects is a demonstration of whether or no the pressure exceeds 0.1 atmosphere, and this question has now been satisfactorily answered in the negative.

[Pg 39]

(b) Sharpness of lines.—The occurrence, as sharp distinct

lines in the spectra of the stellar atmosphere, of lines that are

diffuse in the laboratory at atmospheric pressure, and only become

sharp when the pressure is very much reduced, indicates that the

pressure in the reversing layer must be extremely low. The mere

existence of distinct hydrogen lines points to a pressure of less

than half an atmosphere, as was shown by Evershed,[65] and the lines

4111, 4097, 3912 of chromium,[66] 3421, 3183 of barium,[67] and 4355,

4108, 3972 of calcium,[68] which are sharp and distinct in the solar

spectrum, but which only lose their diffuseness in the laboratory

under vacuum conditions, indicates pressures probably far lower than

0.1 atmospheres. The lines of doubly ionized nitrogen, which are seen

as sharp clear absorption lines in the early stars and the cooler

stars,[69] are also somewhat hazy under even the finest laboratory

conditions,[70] and probably arise in regions of very low pressure in

the stellar atmosphere.

(c) Widths of lines.—The width of an absorption line, produced

by “Rayleigh Scattering” close to resonance conditions, is given by

Stewart[71] as

where

is the observed width of the line,

the

wave-length expressed in the same units, and

the number of

molecules per square centimeter column in the line of sight.

It is unfortunate that the widths of Fraunhofer lines are hard to

measure and difficult to interpret. Results obtained from objective

prism spectra will probably differ from those derived with the aid of

a slit spectrograph, and moreover, in estimating a line with wings it

is hard to judge what should be regarded as the “true” line width.

Russell and Stewart[72] estimate for the

lines in the solar spectrum. Then, on the

assumption that the reversing layer has a thickness of a hundred

kilometers, the partial pressure of neutral sodium in the reversing

layer, as derived by Russell and Stewart from the formula just quoted,

is of the order

. At

the solar temperature, 5600°, about 99 per cent of the sodium present

is in the ionized condition,[73] and thus the total partial pressure

of sodium atoms may be of the order

.

If it be assumed that sodium constitutes about 5 per cent of the total

material present, the total pressure thus derived is of the

order

.

[Pg 40]

The lines are of course the ultimate lines of neutral sodium.

It will be shown[74] in Chapter IX that the partial electron pressure

in the region from which ultimate lines originate is probably between

at maximum. When 99 per cent of the atoms are ionized, the

pressure rises by a factor of about 100, and the corresponding

partial electron pressure becomes between

.

As the total pressure is probably, at the solar temperature, about

twice the partial electron pressure, the total pressure should be nearer

to

.

The total pressure derived in Chapter IX is the pressure corresponding

to the median frequency of the sodium atoms that send out light to

the exterior—it may be regarded as the average pressure for the

visible sodium. The total pressure derived from the line width, on

the other hand, is the pressure at the bottom of the layer of visible

sodium, and might therefore be expected slightly to exceed the average

pressure for the visible sodium atoms. The difference encountered,

partial electron pressure, the total pressure should be nearer to

for the average

pressure, and partial electron pressure, the total pressure should be

nearer to

for the total

absorption pressure, is in the direction that would be anticipated,

although it is larger than might have been expected. Neither value

is, however, of very high accuracy, and probably the agreement can be

regarded as quite satisfactory.

If the same formula be applied to the hydrogen lines, which may have a width[75] of the order of 5Å, high values for the partial pressure of hydrogen are obtained. The behavior of hydrogen in the spectra of the cooler stars,[76] and the abnormally high abundance[77] derived for it in Chapter XIII, suggest that here, again, a definite abnormality of the behavior of hydrogen is involved.

(d) Flash Spectrum.—It was pointed out by Russell and

Stewart[78] that the density in the region that gives the flash